Clinical leaders' top concerns about reopening The key issues to navigate

8 minute read

06 June 2020

David Betts United States

David Betts United States- Doug Billings United States

Natasha Elsner United States

Natasha Elsner United States Hemnabh Varia India

Hemnabh Varia India

As COVID-19 cases recede, we explore how health care organizations can ramp up nonurgent procedures once again—the resources they need, the constraints they face, and the possible timelines for things to come back to pre-COVID-19 levels.

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic forced many health care providers to stop performing nonurgent procedures in response to state mandates, to ensure the safety of patients and staff, and to deploy resources toward COVID-19 treatment. Much lower volumes of these procedures have led to a considerable drop in revenue. As COVID-19 cases recede, how are hospitals and health systems going about resuming these procedures?

In May 2020, the Deloitte Center for Health Solutions surveyed clinical leaders to understand their concerns, approaches, and steps toward resuming nonurgent procedures.

Methodology

Between May 4 and 15, 2020, the Deloitte Center for Health Solutions conducted a short online survey of 50 clinical leaders, including chief medical officers and service line leaders at provider organizations in the United States. These provider organizations included health systems, free-standing hospitals, academic medical centers, and ambulatory surgery centers with an annual revenue of more than US$500 million in the most recent fiscal year.

Key findings

The results suggest that resuming nonurgent procedures will be complex, and clinical leaders are preparing for many uncertainties.

Top concerns include a potential second outbreak, low patient demand, and supplies

Learn more

Explore the health care collection

Visit the Health Forward Blog

Learn about Deloitte's services

Go straight to smart. Get the Deloitte Insights app

While health systems have been at the frontline of caring for patients during the epidemic and have received some financial support from federal legislation, the loss of revenue has been a significant financial challenge for many. Surveyed clinical leaders estimate that the nonurgent procedure volume in April 2020 was just 16% of what it was during the same period last year.

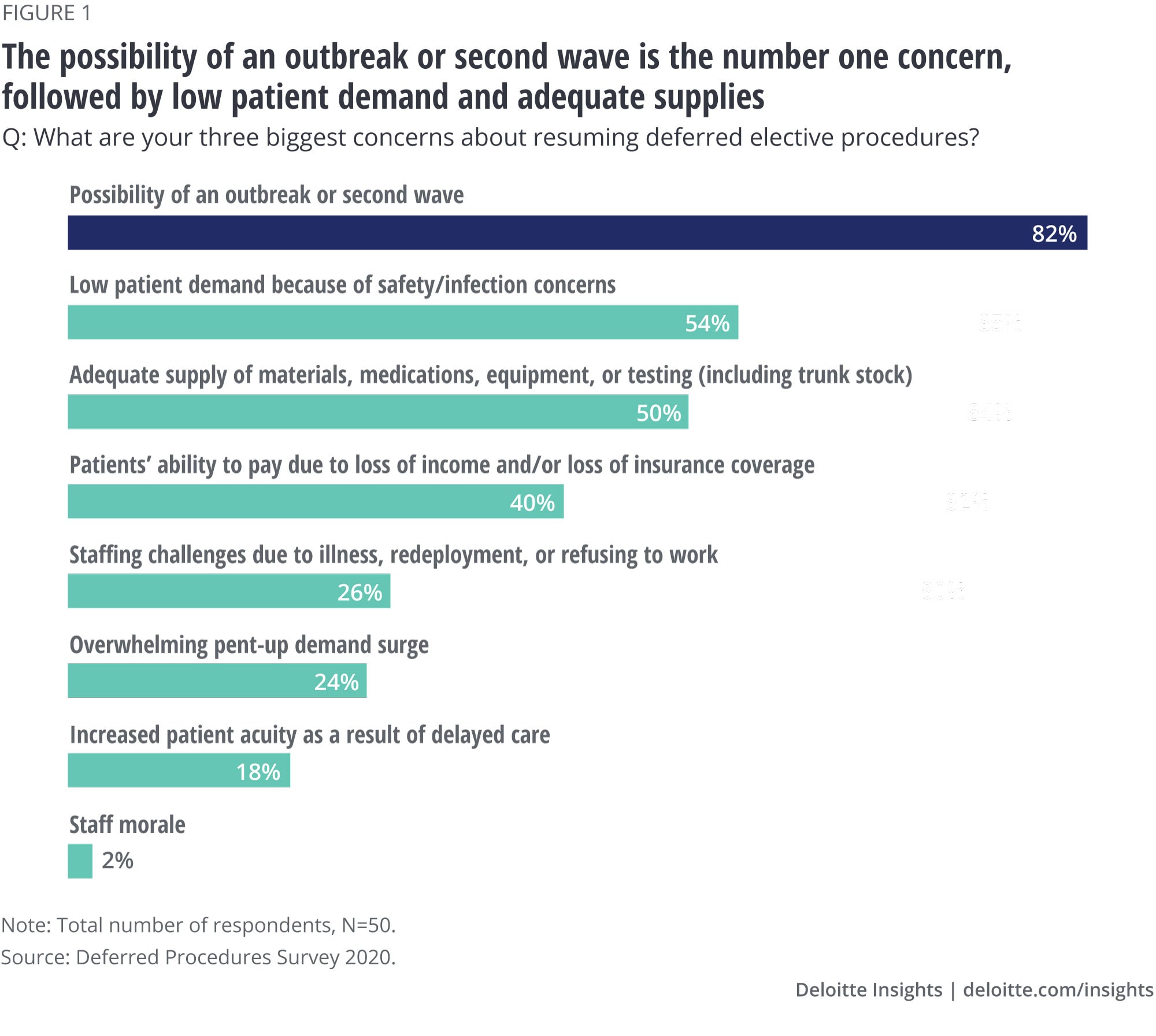

When asked to list their top three concerns about resuming deferred procedures, clinical leaders cite the possibility of an outbreak or a second wave as their number one worry (82%), overshadowing all other concerns. Low patient demand due to safety concerns (54%) and adequate supply of materials, medications, equipment or testing (50%) are a distant second, followed by patients’ ability to pay due to loss of income or insurance (40%).

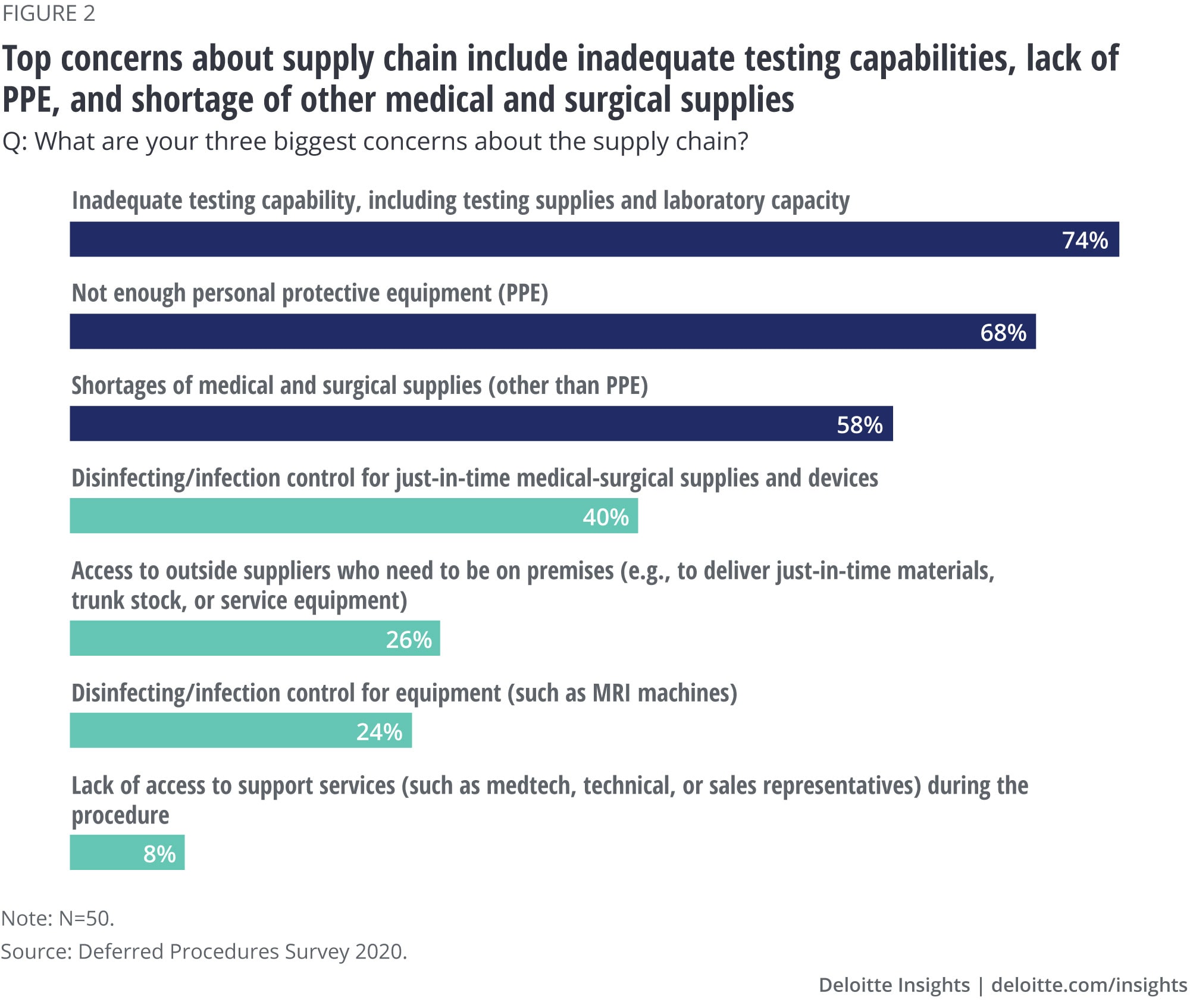

When it comes to supply chain, the top three concerns include testing capabilities (74%), personal protective equipment or PPE (68%), and the availability of medical and surgical supplies other than PPE (58%). These are all areas in which suppliers can support their customers.

Organizations probably have the least control over the possibility of another outbreak or wave. And a large outbreak can have cascading effects on other important variables: patient demand, availability of testing and supplies, and staffing.

Lingering supply chain issues and the possibility of new outbreaks should compel organizations to rethink how they stock, distribute, forecast, and track supplies by site and service line. Providers may have a newfound desire for upstream visibility into the supply chain, whereas suppliers might want a detailed understanding of downstream utilization. This would call for a much closer coordination among supply chain stakeholders: providers, group purchasing organizations (GPOs), distributors, and medtech companies.

Adequate testing is the key capability organizations are looking for

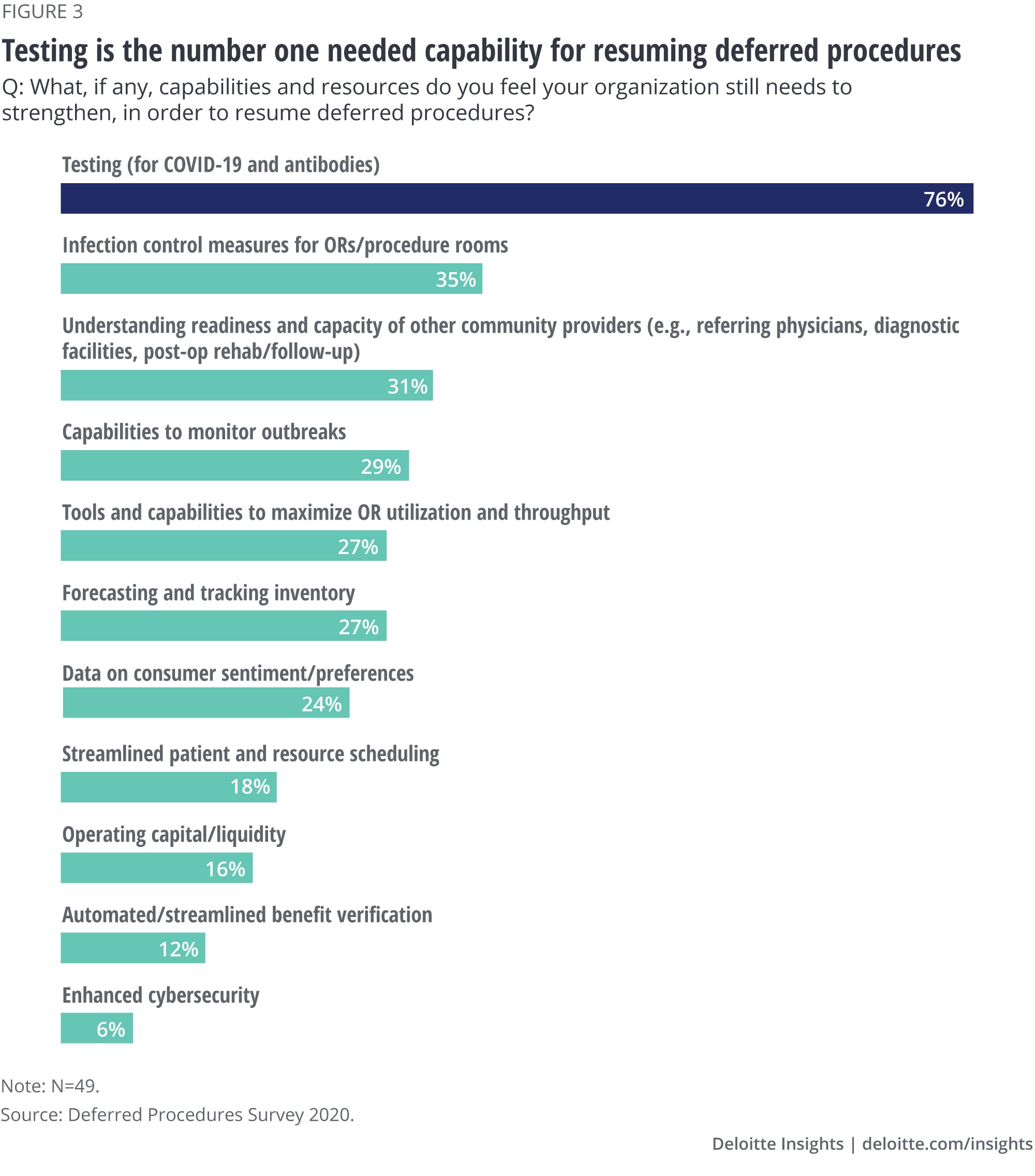

In response to our question about what capabilities are still lacking, sufficient testing (for the virus and for antibodies) tops the list (figure 3).

While both clinical leaders at organization/system level and leaders at the service line level agree about the lack of testing, their perspectives diverge on three other capabilities:

- Infection control for operating and procedure rooms: Only 7% of respondents at the service line level feel this capability still needs strengthening, but a much larger share at the organization/system level (47%) feels this way.

- Understanding readiness and capacity of other community providers (e.g., referring physicians, diagnostic facilities, post-op rehab/follow-up): A much larger percentage of service line leaders (60%) than of organization- or system-level leaders (18%) feel they need to strengthen their organizations’ capability in this area.

- Capabilities to monitor outbreaks: About 21% of organization-level leaders versus 47% of service line leaders think this is lacking.

These differences may be due to different exposure to what is happening at various levels of the organization or multiple locations, or due to the differences in tactical vs. strategic understanding of what is needed.

Organizations are trying to mitigate consumer concerns through virtual health practices and communication

To mitigate concerns associated with resuming deferred procedures, clinical leaders say their organizations are putting in place a number of measures (figure 4).

- Almost everybody (98%) in our survey says their organizations have implemented or plan to implement virtual health practices for some or all nonprocedure visits.

This represents a major shift in practice: the Deloitte 2020 Survey of US Physicians, conducted in January–February 2020 before the COVID-19 pandemic, showed that only 14% of surgical specialists had video visit capabilities and of those who had, a third (34%) were using them. This amounts to just 5% of all surgical specialists having experience with video visits before COVID-19.

- Nearly all respondents (96%) say their organizations have developed or plan to develop an external communication strategy.

However, measuring consumer sentiment is the least common activity being implemented (36%) according to our survey. Consumer perceptions are likely to affect demand for procedures, which 54% of our respondents noted (figure 1). Individuals who need nonurgent procedures tend to be older than the general population (57 vs. 38 years old, on average) and by some estimates more than three in five have at least one comorbidity,1 putting them at a higher risk of severe illness from COVID-19. These consumers may be especially worried about getting their procedures done while the epidemic continues. Health systems should allay consumers’ concerns by tailoring their communications and showing they are able to minimize the spread of infection through adequate PPE for staff and patients and robust infection control.

We expect consumer attitudes and behaviors to be increasingly important for reopening. Organizations should establish market-sensing capabilities to monitor consumer sentiment by key psychographic segments and geographies. These efforts could focus on consumer confidence (including financial outlook, job security, capacity of the health care system), perceptions of safety, and types of services consumers are cancelling or delaying. They could use multiple data inputs and analytical approaches for the purpose—from survey research to social media to internal information on appointment scheduling and testing.

Preplanning and extended hours are the top choices for dealing with potential demand surges

We explored measures being put in place to maximize patient throughput and utilization of operating rooms should there be surges in procedure demand. Surgical preplanning and extending hours of operation are the most common approaches planned or implemented. A quarter of the respondents are not considering approaches to simplify and/or reduce provider preferences, though doing so could help streamline patient scheduling.

Changes to operating hours and scheduling could have implications for external stakeholders such as suppliers, community providers, or medical transport companies, who might need to adjust their practices to help health systems to maximize their capacity.

Even without demand surges, large expenses for treating COVID-19 patients, new and more time-consuming infection control measures, and potential erosion in the payer mix are putting pressure on many organizations to seek efficiencies.

Surveyed clinical leaders expect the return to pre-COVID-19 productivity volumes to take two to six months, with three months being the typical (median) estimate. This relatively optimistic estimate may reflect respondents’ confidence in their organizations’ ability to prepare for reopening.

However, organizations will need to overcome significant operational challenges to reach pre-pandemic productivity. New protocols to minimize infection risk can create inefficiencies and constrain health care systems’ ability to operate at the same capacity as before. Patient scheduling can become more complicated and additional pre-operative testing for the virus and screening patients and staff for symptoms can increase same-day cancellations. Social distancing requirements could mean fewer patients and lower daily caseloads, and additional cleaning and infection controls may slow down room turnover, impacting throughput. It could also mean minimal presence of medical device company representatives or other nonstaff services surgeons rely on to ensure efficiency in their operating rooms.2

Conclusion

Resuming nonurgent procedures may be more complicated and take longer than expected. While everybody is anxious to reopen, the approach should be methodical and allow for contingencies against possible risks to determine when to open, what services to resume, and how to reboot revenue while building resiliency in the system and keeping the patient and the community at the center. Such resiliency will likely require a real-time view of data on consumer sentiment and behavior, the pace and progression of testing, readiness of the clinical and nonclinical workforce, having the operational procedures in place to compartmentalize COVID-19 and non-COVID-19 care, and the financial resiliency to withstand the challenges that organizations may face as they ramp up operations again.

© 2021. See Terms of Use for more information.

Explore more on health care

-

The future of health Collection

-

The economic impact of COVID-19 (novel coronavirus) Article5 years ago

-

Hospital revenue trends Article5 years ago

-

Drug and inpatient spending lines are crossing Article5 years ago

-

Virtual health care Video