To achieve consistent adoption across all virtual health modalities, health care organizations should:

- Identify virtual health use cases with positive short-term ROI. While the regulatory environment creates financial uncertainty, virtual health use cases that don’t generate revenue through direct reimbursement can still produce a positive ROI. For provider organizations, this can happen when multiple metrics (provider productivity, practice capacity, access to care, and quality) are positively affected, particularly in profitable service lines such as orthopedics or capacity-constrained areas such as primary care. As organizations move away from fee-for-service to value-based care, they can expand their virtual health programs, adding use cases that may not make financial sense today but could in the future.

- Evaluate investments in care management capabilities built upon a virtual health foundation. Nonvideo virtual health modalities can support care management for patients with chronic conditions, an area of the health care delivery system that would benefit from more touch points and tools. In our Future of HealthTM vision, we expect care models to increasingly move from transactional to longitudinal. To achieve this, health care organizations should invest in a comprehensive care management program that supports continuity of care. Virtual health modalities beyond video visits are an essential component of such a program. Although designing a care management program may feel like a maiden voyage, organizations don’t have to start from scratch: They can borrow from health insurers’ and disease management companies’ playbooks when it comes to risk stratification, member engagement, gamification, and incentives, and outsource certain elements of the program.13

Call to action: Ensure that virtual health meets the needs of—and is accessible to—all patient populations

While virtual health visits are more convenient because they often eliminate the need to travel, find child care, and take time off work, the issue of access isn’t always as straightforward. Studies of virtual health utilization from claims and EHRs show that in the period of 2020–2021, patients with all types of insurance had similar access to virtual health, while the uninsured population had lower access.14 Some studies found that access for underserved populations has improved as a result of virtual health, while others indicate that the digital divide (known as the gap between those with and without access to technology) has exacerbated inequities. For instance, underserved populations were more likely to rely on audio-only and messaging services.15 On balance, virtual health’s effects on access appear to be mixed.16

In our consumer survey, the digital divide is expressed by differential use of virtual health based on income and reliability of internet service. Nearly half of consumers (46%) with very good/reliable internet service had a virtual visit in the last 12 months, compared with 31% of those with very poor/unreliable internet service. Although most consumers (81%) have broadband access, only half (52%) describe it as reliable and meeting their needs. Not surprisingly, households with the highest incomes are the most likely to have reliable internet service. Sixty-three percent of consumers with an annual household income greater than US$100,000 have reliable internet, compared with 46% of those making less than US$50,000.

When we asked physicians about the effects of virtual health on access to care for underserved groups, more said virtual health has increased access (39%) than decreased (7%) while 12% said it had no effect and 25% said the effects were mixed. This is a relatively optimistic view when compared to utilization studies and our consumer survey findings that show mixed effects on access. Interestingly, physicians who have implemented virtual health in their practice are much more positive about its effect on access.

To narrow the digital divide, health care organizations can collaborate with local governments, utility providers, and businesses in their community (such as shopping centers, schools, shelters, libraries, and pharmacies) to provide free Wi-Fi and digital devices that can be used to receive virtual health services. For instance, Texas A&M Health Science Center collaborated with OnMed to place kiosks in a rural Texas community to measure patients’ vital signs, dispense common medications, and facilitate on-demand video visits with a nurse practitioner.17

Leaning on virtual health technologies to deliver state-of-the-art care

Our view is that virtual health is not a substitute for how care has traditionally been delivered. Instead, it offers new ways of care delivery that were not possible in the past. When done well, virtual health can improve care quality and continuity, reduce friction, and address health equity. And although there is still a lot to learn and improve on, organizations should assess their current maturity, reflect on how virtual care can help align with strategic goals, and begin to implement the following steps:

- Educate, support, and equip physicians to infuse the human element of care in virtual health encounters

- Rethink existing care models and assess how to prioritize virtual health investments for future care models

- Ensure virtual health is accessible to, and meets the needs of, all patient populations

- Develop a thorough understanding of the human experience of receiving and providing care, apply a thoughtful approach to workflow redesign, technology applications, and the use of care teams, and follow a careful change management plan

- Involve physicians, patients, and other care team members, and value their input while designing and implementing human-centered virtual health offerings and workflow processes

- Consider regulatory and policy issues that may impact your model, advocate for flexibility in virtual health design, and support associated adequate reimbursement

These steps can help satisfy consumers’ appetite for virtual health and digital technology and position health care organizations for a Future of HealthTM that centers on digitally enhanced, frictionless, affordable, high-quality, and equitable care.

Appendix. Study methodology

Appendix 1. Methodological notes: 2022 Deloitte Survey of US Physicians

Since 2011, the Deloitte Center for Health Solutions has surveyed a nationally representative sample of US physicians on their attitudes and perceptions about the current market trends impacting medicine and the future state of the practice of medicine.

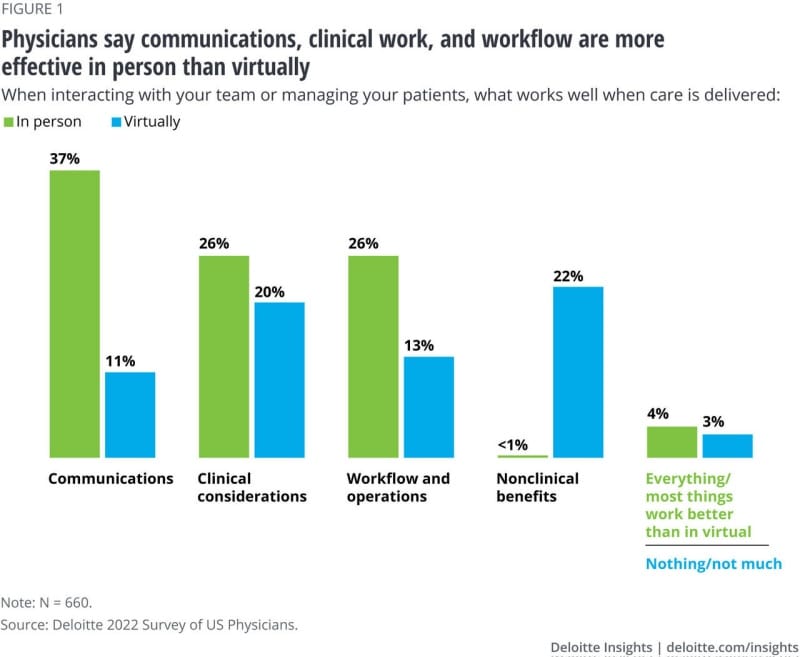

The biennial survey was fielded between January 18 and March 20, 2022. This survey of 660 physicians is nationally representative of US primary care and specialty physicians with respect to years in practice, gender, geography, practice type, and specialty.

The general aim of the survey is to understand physician adoption and perception of key market trends of interest to the health care industry and policy. In 2022, 660 US primary care and specialty physicians were asked about a range of topics, including virtual health, digital technologies, care teams, health equity, and value-based care.

Sampling approach

We selected a random sample of physician records with complete mailing information from the American Medical Association (AMA) Physician Masterfile, and stratified it by physician specialty, to invite participation in an online 20-minute survey.

The resulting study sample is representative of the AMA Physician Masterfile with respect to years in practice, gender, geography, practice type, and specialty to reflect the national distribution of US physicians.

About the AMA Physician Masterfile

The AMA is the major association for US physicians and its Physician Masterfile contains records of more than 1.4 million US physicians (including AMA members and nonmembers) and is based upon graduating medical school and specialty certification records. It is used for both state and federal credentialing as well as for licensure purposes. This database is widely regarded as the gold standard for health policy work among primary care physicians and specialists, and is the source used by the federal government and academic researchers for survey studies among physicians.