Building resilience in refining Navigating disruption and preparing for new opportunities

23 minute read

26 October 2020

Downstream oil and gas companies should rethink their value proposition and leverage opportunities for outperformance across five key areas to navigate long-term challenges from declining fuel demand and the energy transition.

Unprecedented turmoil in oil and refined products markets exposes downstream risks

While COVID-19 has impacted a range of industries from leisure and travel to retail, oil and gas is one industry that has been hit particularly hard by the demand destruction caused by the pandemic and the simultaneous production increases and price cuts by the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC). Following the sharp drop in fuel demand, refining margins dropped below zero for the first time since 2013. The recovery has been uneven. Demand for gasoline has risen as more cars have returned to the road and as shops, retail stores, and restaurants have reopened. However, demand for jet fuel has remained anemic, with US demand still half of its pre–COVID-19 levels, as many people defer air travel.

Learn more

Explore the Building resilience in oil, gas, and chemicals collection

Browse the Oil, gas & chemicals collection

Learn about Deloitte’s services

Go straight to smart. Get the Deloitte Insights app

Refined product demand recovery will likely vary by region over the next few years, with some countries and US states fully reopening their economies as COVID-19 is contained, whereas others may struggle with second- and third-wave infections.1

In addition to the immediate challenges presented by COVID-19, downstream oil and gas companies also face longer-term challenges from the energy transition. Many consumers, investors, and regulators are pushing to reduce carbon emissions from transport as part of the energy transition, including the more widespread adoption of electric and alternative fuel vehicles as well as implementation of stricter fuel economy regulations such as the Corporate Average Fuel Economy (CAFE) standards in the United States. In fact, US gasoline consumption could decline by 15% by 2030 as older, less-efficient vehicles are replaced by newer, more fuel-efficient models.2

Even as US downstream oil and gas companies contend with shrinking domestic markets, opportunities for increasing exports could dry up as well. Fast-growing markets in Asia have imported only small quantities of refined products from the United States. For example, China, India, and Vietnam have imported less than 10,000 barrels per day (bpd) of gasoline, distillate, and jet fuel combined from the United States over the last five years.3 Additionally, these countries are investing heavily in their own domestic downstream infrastructure, reducing potential future import growth. Nearby markets in Latin America—historically large buyers of US exports—may prove to be saturated, providing few avenues to export excess refined products.

Over the next 10 years, many downstream companies could face lower consumer demand, declining refinery utilization, and slower revenue unless they position their business for the new challenges.

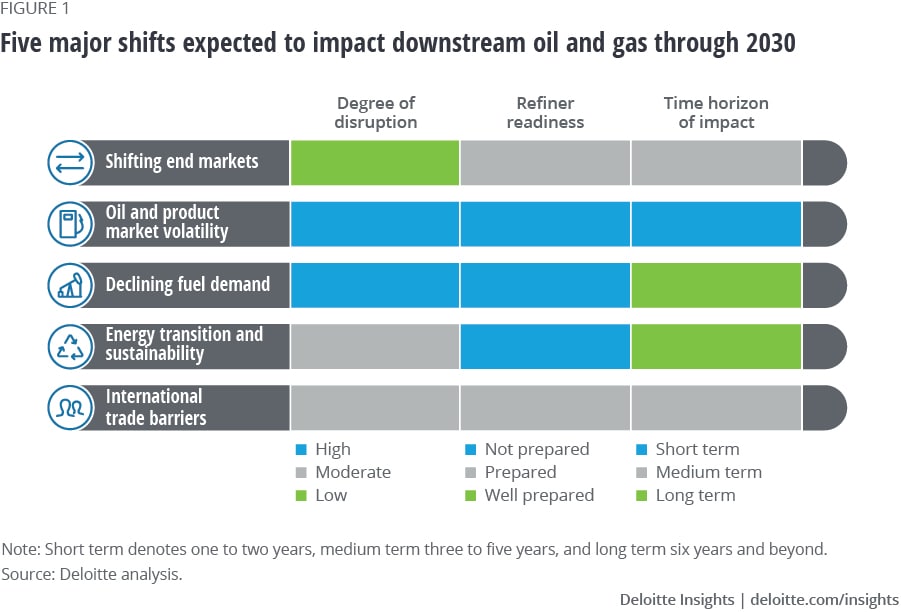

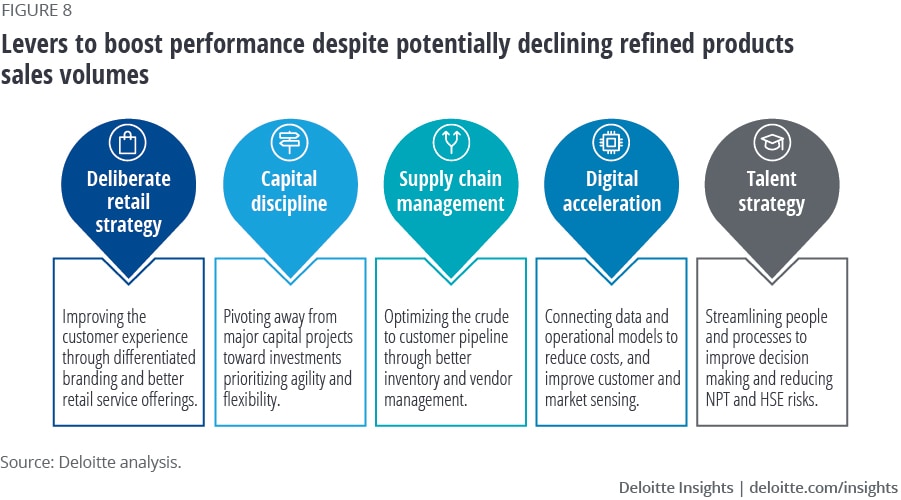

Over the next 10 years, many downstream companies could face lower consumer demand, declining refinery utilization, and slower revenue unless they position their business for the new challenges. They will need to navigate the impending headwinds and unfavorable market conditions—some short term and others long term—that reflect shifting consumer preferences, investor expectations, and tightening regulations. In many cases, the industry is not prepared for the potential disruptions, which include major shifts in end-markets; increased oil and refined product price volatility; longer-term declining fuel demand; the continuing energy transition; and challenges tapping international export markets (figure 1). These major shifts could have significant implications for their businesses, and oil and gas companies should consider various opportunities for outperformance, including deliberate retail strategy, capital discipline, supply chain management, digital acceleration, and talent strategy. Ultimately, they should reduce operating costs, grow their market share, and better optimize their crude-to-customer pipeline to boost earnings even if revenue growth proves marginal.

Refined product demand dried up as global oil markets crashed

The impact of the pandemic on the oil and gas industry has been swift, with the sudden decline in travel translating into lower fuel demand and higher inventories, leading to historically low prices. On March 9, Brent prices fell more than US$10 per barrel to US$35—the lowest one-day nominal drop in the 40 years it has been widely traded. Subsequently, Brent prices dropped further to less than US$10 in April—the lowest in over 20 years.4 Regional prices were impacted even more in some cases. For example, on April 20, West Texas Intermediate, the US crude benchmark traded briefly at negative prices, reaching almost minus US$40 per barrel before rebounding to positive territory the next day.5

While oil prices have dropped rapidly before, 2020 has been different. Unlike the declines in 2014, which was driven by increasing shale production, or 2008, when the recession had a short-lived impact on oil markets, COVID-19 has hit demand directly. This has led to a decrease in global manufacturing and services activities, reshaping many workplaces, and reducing US car and air travel to a fraction of pre–COVID-19 levels. Globally, refined products consumption fell by almost 30% in the first quarter of 2020 and is projected to be 91.9 million bpd in 2020, down 8% year on year.6

Globally, refined products consumption fell by almost 30% in the first quarter of 2020 and is projected to be 91.9 million bpd in 2020, down 8% year on year.

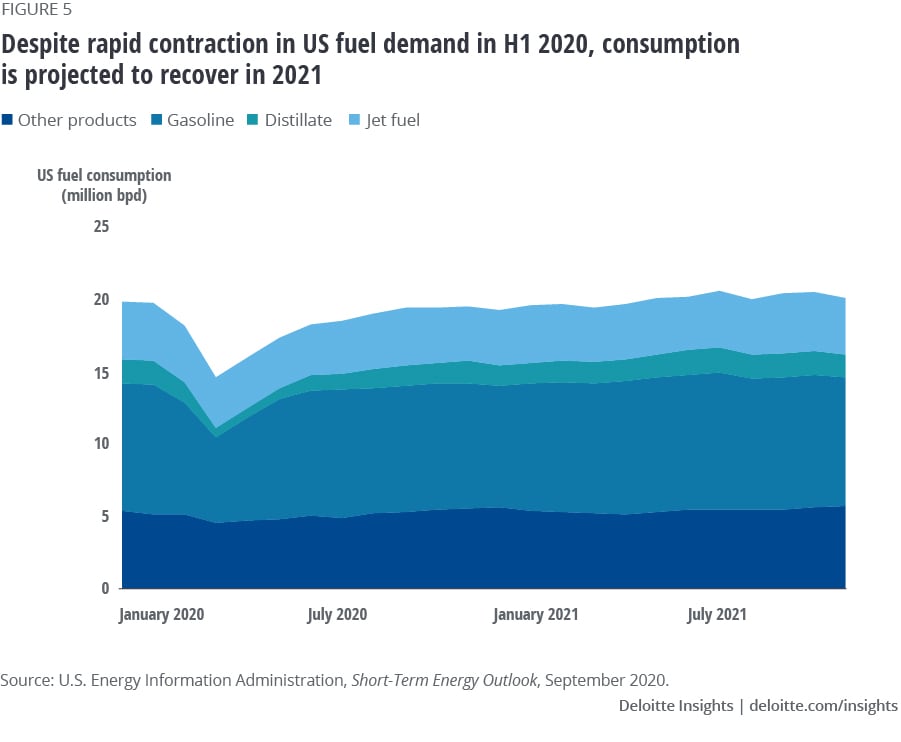

The story has been similar in the United States, where fuel consumption fell from almost 20 million bpd to less than 15 million bpd in a matter of weeks, and remains well below pre–COVID-19 levels.7 Unsurprisingly, global oil inventories have risen, peaking at 86 days, well above the 60-day five-year average. But so have US gasoline and diesel stocks, with July inventory figures being 10% and 20% more than the five-year average respectively, limiting the benefits of lower prices on refining margins.8 Lower prices have led to lower refinery throughput and shifting yields, translating into lower downstream revenues and margins. These shifts are likely unsustainable. Ultimately, downstream oil and gas companies will likely not fully recover until the broader economy recovers.

US refinery revenue and earnings drop sharply in first half of 2020

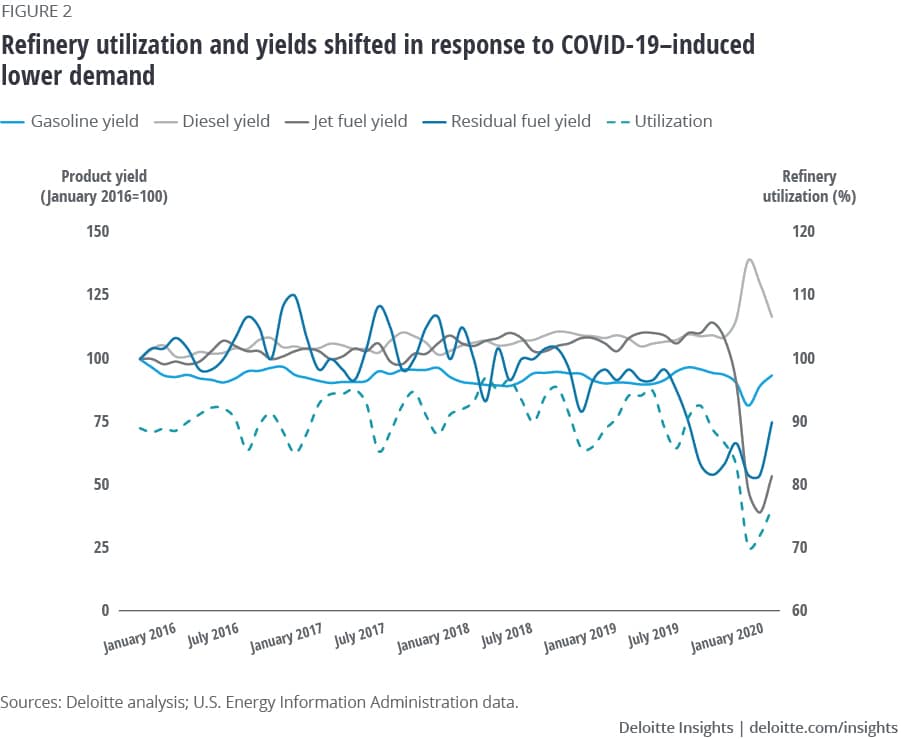

US refinery revenue and earnings dropped precipitously in the first half of 2020. Prior to the widespread impact of COVID-19, refiners operated in relatively favorable market conditions. Following the oil price crash in 2014, US refining revenues and earnings were robust, with lower oil prices translating into higher net margins—averaging close to 15% since 2015 compared to the substantially higher margins between 2010 and 2014. As demand for gasoline and jet fuel dropped in March, domestic refinery utilization fell from almost 90% to 70% before partially recovering to almost 80%. At the same time, refiners adjusted their yields to accommodate changing demand patterns, producing proportionately even less jet and residual fuel as total throughput fell (figure 2).

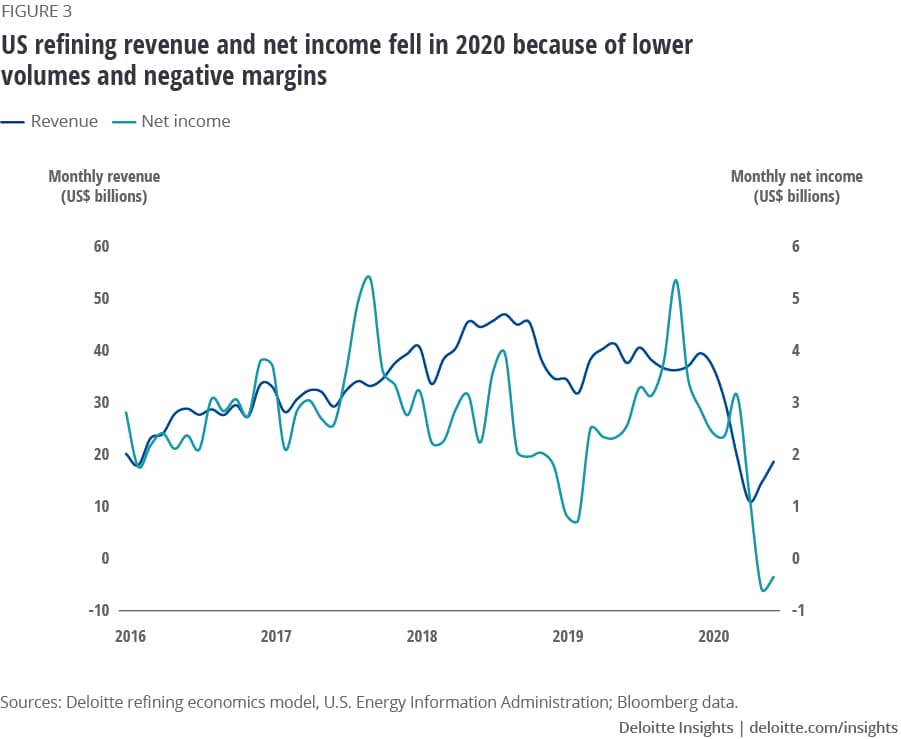

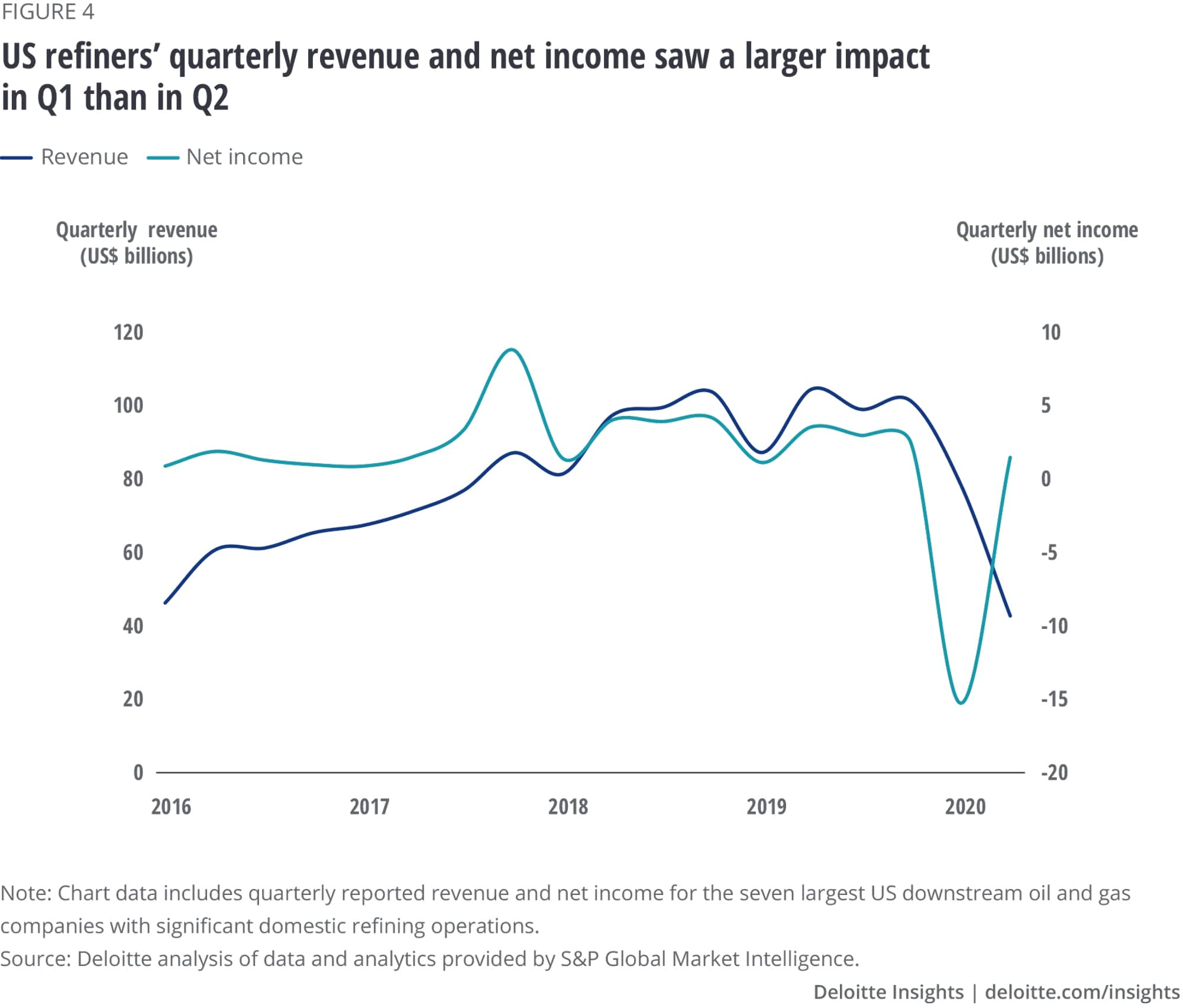

Despite the shifts in yields, lower utilization and declining product prices took a bite out of sales with overall estimated US refining revenue falling 60% quarter on quarter. Perhaps unsurprisingly, estimated US-wide refinery income turned negative in 2020 for the first time since 2013 (figure 3). Reported quarterly revenue and earnings of the largest US downstream oil and gas companies correlated with our monthly estimates. However, due to the lag crude acquisition and product sales, as well as the impacts of inventory effects, the impact of COVID-19 were felt more sharply in Q1 than in Q2 by these companies (figure 4). The overall magnitude of the impact was similar between monthly estimates and quarterly reported data.

Even as reported revenue fell in Q2, net income rebounded because oil prices fell in line with product prices. In addition, volumes sold will likely remain low in the short-to-medium term. Volume growth will likely be weaker in the 2020s even after the economy recovers if current regulatory and mobility trends continue. Moreover, if fixed operating costs can’t be reduced, the decade could be marked by weaker earnings even as the short-term impact of COVID-19 passes.

Oil and gas demand recovery could be slow even after COVID-19 is contained

The short-term path to recovery is uncertain, with a range of alternative indicators sending mixed signals. While car travel is up by 160% by some measures since its April nadir, daily commuting in major US cities remains 70% below pre–COVID-19 levels.9 Air travel also remains down—30% below pre– COVID-19 levels.10 With COVID-19 cases increasing across several states, the likelihood of widespread business reopenings, leisure travel, and a return to retail shopping and restaurant dining may prove remote in 2020 for many large US cities.11

The medium-term path to recovery for different countries will likely be different because of their diverging ability to contain the spread of the pandemic, particularly as regional flare-ups lead to second and third waves of infections. The International Energy Agency projects that global consumption will rise from 91.9 million bpd to 97.1 million bpd in 2021. However, this is still almost 3 million bpd below 2019 levels.12 The United States is expected to be more resilient, reaching 2019 levels by mid-2021 (figure 5). Any fuel demand forecast requires significant caveats, with consumption tied heavily to both economic growth and the ability of individuals to travel safely, both in part a function of the spread and severity of COVID-19 over the next 12 to 18 months.

For fuel demand to return to pre–COVID-19 levels by 2021, two things likely need to happen: First, the trend of working from home would need to shift back because 15% of daily trips are taken to commute to and from work—representing a significant source of gasoline demand, which itself is roughly 45% of US refinery output.13 Second, both domestic and international air travel would need to return some semblance of normal, even if they remain below 2019 levels for several years. This may prove to be a bridge too far, particularly for international flights, unless current traveler sentiment trends change. The International Air Transport Association projects that air travel could remain 30%–40% below pre–COVID-19 levels even in 2021—indicative of a long-term drag in jet fuel demand. Additionally, deliveries of new planes dropped 50% in 2020 and passenger air traffic can take up to five years to recover. The industry could shrink by as much as 20% compared to 2019 peak levels over the next few years. This bodes poorly for refiners because prior to COVID-19, jet fuel comprised another 10% of US refinery output.14

While the early-to-mid 2020s could be a period of recovery and demand growth for some fuels, business as usual will likely not return anytime soon. This leaves downstream oil and gas in a bind. Second quarter utilization rates were at decade lows, with margins drifting downward and remaining negative for many refiners over the past few months. Even though utilization will likely increase through H2 2020, the demand for some products such as jet fuel could be low for several years, preventing many refineries from fully returning to pre–COVID-19 run rates.15 And it’s not just the short or medium term, the long-term outlook will also likely require refiners and retailers to adapt to shifting markets.

Over the next few years, the fuel markets will likely recover from the impact of COVID-19 and other cyclical factors, but downstream oil and gas companies could also face several longer-term, structural challenges. These challenges will likely include declining fuel demand; rising carbon constraints; competition from EVs and alternative fuels such as ethanol, biodiesel, compressed natural gas (CNG), and hydrogen; and increasing international competition. These headwinds could lead to a 15% decline in US gasoline consumption, not offset by increased refined products exports.16 Less demand, and therefore, lower refinery throughput, combined with fixed operating costs, could permanently lower US downstream companies’ earning potential if they don’t take steps to increase margins and find new outlets for their products.

Post–COVID-19, the energy transition may reduce long-term refined product demand

The growing focus on emissions reduction and the energy transition could put downward pressure on fuel demand in the United States. First, US fuel economy regulations including CAFE standards will reduce gasoline consumption over the next 10 years. These standards, first enacted in 1975 to improve the fuel efficiency of light-duty vehicles such as passenger cars, pickup trucks, and sports utility vehicles, have shaped fuel demand in the United States. The requirements were tightened significantly during the Obama administration, leading to a 30% increase in fuel economy for light-duty vehicles over the last decade, with further efficiency gains targeted through 2025. These regulations had a significant impact on fuel demand in the United States. For example, the number of vehicle miles traveled in the country increased by 10% between 2010 and 2019, but domestic gasoline demand only rose by 3% over the same period.17

The current administration issued a new rule—Safer Affordable Fuel Efficient (SAFE) Vehicles Rule—that pared back increases for future models, but still requires future cars and trucks to be more fuel efficient than today’s models.18 Considering the average age of light-duty vehicles is more than 10 years, this rule is expected to lead to lower per-mile fuel demand through the 2020s and into the 2030s in the absence of a more substantive rollback of fuel efficiency regulation. Similarly, new standards have been implemented for heavy-duty vehicles, targeting trailers and heavy-duty pickup trucks, and are expected to reduce fuel consumption by 9% and 17% respectively by 2027. Some efficiency gains may be offset by consumers purchasing larger vehicles, but the overall downward trend will likely continue.

Even if internal combustion engine efficiency gains plateau in the 2020s, US gasoline demand could decline because of increased EV adoption. In Utility decarbonization strategies paper, Deloitte estimated that US plug-in hybrid and battery electric vehicle sales could be between 2.7 million and 2.9 million in 2030—an order of magnitude higher than the 330,000 EVs sold in 2019. This could potentially comprise 15%–20% of total US light-duty vehicle sales by the end of the decade.19 As battery costs decline and charging infrastructure availability increases, EV competitiveness against internal combustion engine vehicles will likely only increase, leading to increased downward pressure on US domestic gasoline demand.

As EVs are becoming increasingly popular, alternative fuels such as biodiesel and hydrogen could also become more widely accessible over the next 10 years. The near-to-medium term threat to traditional downstream players is likely limited, but alternative fuel production is growing rapidly from a small base. Today, US renewable diesel consumption is less than 40,000 bpd, much less than the 3.5 million bpd of distillate consumed domestically. By 2030, it could plausibly double.20 Additionally, almost 1 million bpd of ethanol is sold for blending and use as transport fuel.21 While historically most gasoline sold contains up to 10% ethanol, changes in regulations aimed at reducing fossil fuel consumption could lead to increased availability of higher ethanol content fuel.

Beyond biofuels, CNG and hydrogen fuel cell vehicles could increase rapidly depending on regulations and financial incentives. Natural gas already powers roughly 25% of US transit busses and could make economic sense for other heavy-duty vehicles, including those used in local deliveries and long-distance trucking. There are less than 10,000 hydrogen fuel cell cars on the roads in the United States today, in part because infrastructure is lacking for hydrogen fuel cell vehicles outside of California.22 However, regional penetration could increase if fueling stations become more prevalent. Biofuels and alternative fuel vehicles will not likely displace fossil fuel demand in the short term and each individual fuel represents only a small fraction of the current fuel market. However, the increase in access to EVs and alternate fuel sources will likely incrementally reduce refined product demand growth in the short-to-medium term and could displace it in the longer term.

The impact of new regulations promoting fuel efficiency, EV sales, and access to alternative fuels could be more than offset by refined products exports. However, the opportunities for export growth could prove limited due to saturated end markets and increasing international competition. The United States exports more than 800,000 bpd of gasoline, 1.3 million bpd of distillate, and 200,000 bpd of jet fuel—amounting to more than 10% of total production. Most product exports go to the Caribbean and to Latin America, particularly Mexico. The United States exports few barrels to fast growing countries in Asia.23 This could make it difficult for US downstream oil and gas companies to increase exports to offset lower domestic consumption. US gasoline exports to Mexico were equivalent to 65% of its domestic consumption in 2019, making it difficult for US refiners to increase market share.24 This number was practically 0% for China and, because of overcapacity, US exports will not likely be competitive against Chinese barrels in the short-to-medium term.25 Considering the ambitious refining growth targets of other Asian economies, the region will not likely be a major source of US export demand.

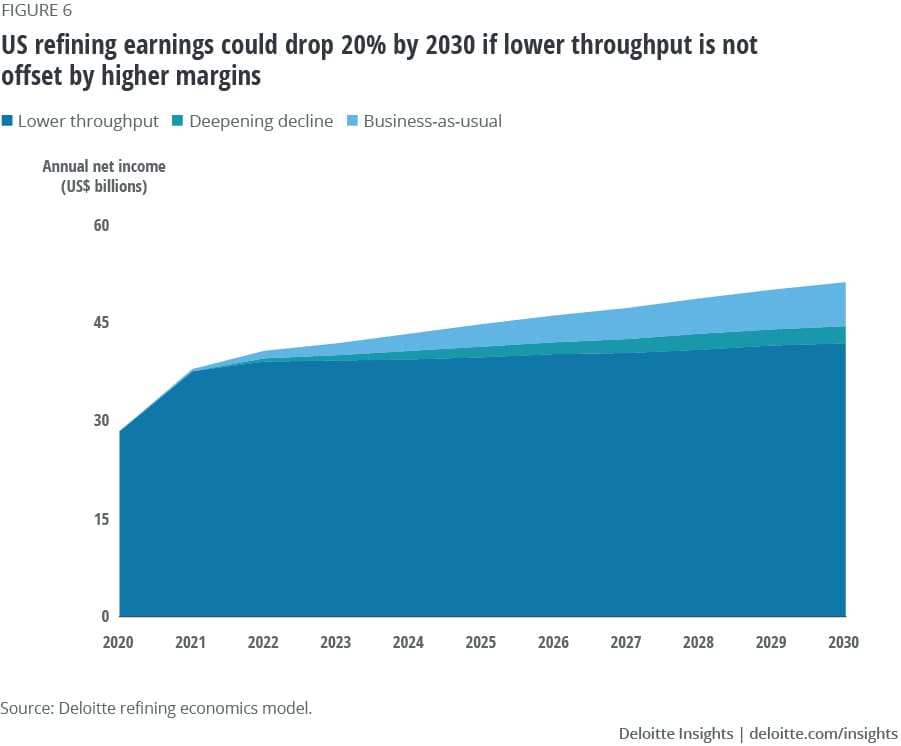

If refined products exports do not increase substantially over the next decade, refinery throughput could fall from 17 million bpd in 2019 to 16 million bpd in 2030. Moreover, if throughput does decrease, a “deepening decline” scenario by 2030 could lead to 2.4 million bpd fewer barrels refined compared to a “business-as-usual” scenario where utilization remains robust and US refining capacity continues to grow incrementally each year. If lower throughput is not offset by reduced fixed operating costs, net income could be flat for most refiners over the next decade and 20% lower than what would be expected if historical growth continued (figure 6). To offset these declines, downstream oil and gas companies can boost their margins by reducing costs, optimizing their supply chain, and increasing market share. This will be particularly important for companies in the Northeast and the West Coast that could face declining fuel demand sooner than in other parts of the country (see sidebar, “The mobility evolution will be regionalized.”)

The mobility evolution will be regionalized

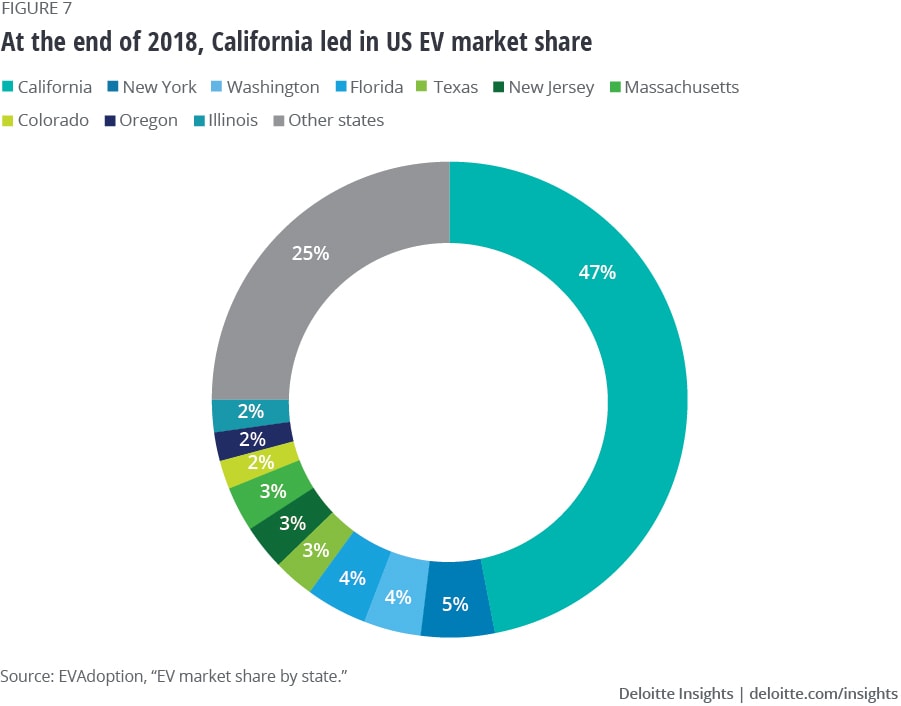

The impact of changing mobility preferences—and more broadly the energy transition—is not expected to be homogeneous across the United States. It will likely vary by city, state, and region. By the end of 2018, almost 50% of all EVs sold were in California, followed by New York, Washington, and several other highly populous states (figure 7). EV sales as a percentage of total light-vehicle sales were higher in several of these states as well, particularly on the West Coast, where EVs represented 7.8%, 4.3%, and 3.4% of vehicles sold in California, Washington, and Oregon, respectively—well above the nationwide 2% market share.

Because of EVs’ current limited range and their need for proximate charging infrastructure, sales are expected to primarily grow in urban areas in states with stronger alternative fuel vehicle incentives. As EV sales jump from 300,000 per year in 2019 to almost three million by 2030, sales will likely continue to be concentrated in many of the same places where they are today. If total EV sales grow to be almost 15%–20% of the US market by 2030, it could exceed 50% in some states in the Northeast as well as the West Coast. In Petroleum Administration for Defense District (PADD) 1 and PADD 5, which include states from the Northeast and the West Coast, respectively, the decline in gasoline demand could be substantially higher than the 15% projected for the United States overall.

Downstream oil and gas companies in these PADDs will likely need to adapt to more rapid and sustained market shifts because of the accelerated adoption of EVs, alternative fuel vehicles including those powered by hydrogen fuel cells, and stricter state environmental regulations. Refiners in PADD 5 could face more challenges due to limited pipeline access to other regions and varying fuel specification requirements, including those set out by the California Air Resources Board.26 And it’s not just gasoline, California regulations could also lead to substitution of renewable and lower-carbon fuels for fossil-fuel derived diesel.27 PADD 5 refineries have been engineered to meet specific regional needs and will not likely be easily adaptable to either other US PADDs or international export markets, exacerbating the challenges that downstream companies face across the United States. Over the longer term, downstream operators in these regions should focus on reducing excess capacity and building new, greener operations to meet local market needs.

Five opportunities to outperform in the face of challenging market conditions

For many US downstream oil and gas companies, the 2020s will not be a decade marked by volume growth. However, there will likely be opportunities for increased revenues and earnings if they successfully adapt to changing market conditions. In the short term, refiners have limited room to maneuver, squeezed by volatile oil and products prices, with many lacking the flexibility afforded by storage and distribution networks as well as a large-scale retail footprint. What will be key is expanding market share—or finding new markets—while reducing operating costs and improving supply chains to optimize the crude to customer pipeline. Five levers can help downstream oil and gas companies outperform despite the challenging market conditions: deliberate retail strategy, capital discipline, supply chain management, digital acceleration, and talent strategy (figure 8). Using these tools can increase the total value captured from refining, distributing, and selling a barrel of oil while reducing market risks inherent to the industry.

Deliberate retail strategy

Differentiation can be challenging for companies in commoditized markets such as transport fuels. Retail stations connect refineries with their end customers, but often downstream companies sell their products through channel partners or in wholesale markets. If demand for refined products decline in the United States over the next 10 years, rising retail market penetration can help increase market share and provide customer demand data. Even for downstream companies that sell their products through third-party operated distribution and retail networks, improved partner relationships and integration of retail data into existing operational modelling can provide benefits.

Over the past few years, foot traffic in convenience stores and retail stations has increased 16%, creating opportunities for downstream companies to grow through the tail-end of the value chain.28 Not only is the number of convenience stores increasing, there’s also been a rise in the number of businesses beyond retail gas stations in transport-adjacent industries such as meal delivery and ride-sharing. Across industries, availability and convenience are typically the top reasons consumers choose retailers.29 The consumer push toward convenience has negatively impacted most fuel retailers, with strong backcourt competitors gaining market share.30 In particular, retail outlets that focus on either premium products and services or on value have outperformed those that try to do both. A deliberate retail strategy can be critical in increasing differentiation and financial performance. This can be important for refiners as well as retail station operators, as downstream companies that can improve the customer experience through wholly owned or partner-operated retail stations can potentially increase their fuel sales. They can also boost margins through additional sales from convenience store goods and services, including faster growing digitally intermediated products.

Capital discipline

Capital discipline has always been important in downstream because it’s a volatile, commoditized industry. However, the challenges will likely only increase over the next decade because of potentially declining demand and an existing large, legacy asset base. Unlike the recent boom in greenfield petrochemical investments, US downstream investment has focused on brownfield projects and debottlenecking. These smaller scale investments have focused on incremental growth, with refining capacity increasing 7% since 2010. Going forward, capital allocation will likely need to focus on agility. Part of that means investing in more advanced refinery units that increase yield flexibility, but it also means reducing capital spending while still maintaining access to broad distribution networks needed to gain access to customers and markets.

Three steps can help conserve capital while meeting demand. First, downstream companies should look to divesting noncore refining assets, particularly those without access to other domestic and international markets. Second, they should assess the viability of converting refineries into storage and distribution channels, or in some limited cases, biofuels production plants. Last, high cost, underperforming refineries should be retired to improve profitability of other assets. All three options should be on the table to protect margins throughout the commodity price cycle.

Supply chain management

By focusing on capturing value in individual parts of the supply chain—from crude procurement and product slate to distribution and retail—downstream companies may fail to maximize overall value generation for the entire organization. Part of the challenge is simply better inventory management and connecting economic and operational models to market data. The other part is lack of agility. In the first half of 2020, both crude and product prices fell sharply as fuel demand dropped but oil supply remained robust. For some of the largest refiners that led to higher feedstock costs as well as lower revenues and negative net income because they were caught in between a large swing in the energy markets.

While downstream companies can’t avoid the ups and downs of the commodity markets, taking steps to increase their supply chain sophistication can mitigate some of the price and volume risks they face. First, downstream can proactively gauge shifts in product demand through better market-sensing. Second, implementing a more systematic hedging program can reduce price dislocation and ensure margins. And third, integrating crude procurement, refinery economic models, and distribution networks can incrementally increase per-barrel margins not just at the refinery gates, but also at the tanker rack and gasoline pump.

Digital acceleration

Digitalization can drive better talent, supply chain, and commercial strategy by generating more data, including from novel sources. For example, credit card and sales data can provide insight into consumer demand for fuels and improve sales and trading models. Real-time storage availability, inventory, and refinery operation data can improve asset utilization and increase margins by better connecting supply to demand. And better vendor and personnel management software and analysis can cut redundant costs and reduce waste.

However, downstream companies should take a more holistic approach to digitalization to fully benefit from automation as well as data generation and analysis. To ensure such an approach, these companies should identify gaps in the data and points of connection between the different systems used in different parts of the business. If these gaps can be addressed, retail and markets data can be leveraged to increase margins and cut costs through integrated digital-physical systems.

Talent strategy

Unlike upstream oil and gas and oilfield services, downstream companies may not be able to ramp up and down employment based on market conditions. After all, much of their operations involve fixed assets like refineries and tank farms with the last mile of distribution and sale networks being owned by channel partners. For those without retail operations, upgrading controls, equipment, and software can streamline the decision-making process and reduce overall headcount needed to operate and maintain assets. Similarly, technology can be used to pare back back-office activities by automating functions such as data gathering and report generation. For those with distribution and retail assets, rethinking their approach to talent may be more challenging. Here, too, however, technology can help increase productivity and reduce costs by better matching talent supply to demand. This can be particularly true for organizations who have recently acquired or divested a significant number of assets and need to resize their talent strategy to match their new operational footprint.

Building a more resilient refiner

Downstream oil and gas has historically been a challenging industry with high upfront capital costs, limited opportunities to manage margins, and relatively slow domestic demand growth. The rapid decline in fuel demand and prices caused by the spread of COVID-19 exposed some of the long-term risks refiners will face if domestic fuel consumption declines and is not offset by increased international exports. Oil and gas companies often have large, legacy asset bases with fixed costs and little operational room to maneuver. To sustain long-term profitable growth, these companies will likely need to rethink their value proposition and how they can increase and better capture the value they generate. Focusing on deliberate retail strategy, capital discipline, supply chain management, digital acceleration, and talent strategy can help downstream oil and gas better adapt to shifting markets and potentially declining fuel demand.

More in Oil, gas & chemicals

-

Oil’s well?: Divergence and imbalance in the oil and gas ecosystem Article6 years ago

-

Shale’s next act Article5 years ago

-

One Downstream Article5 years ago

-

Refining & marketing: Eyeing new horizons Article6 years ago

-

Refining at risk Article7 years ago