Oil’s well?: Divergence and imbalance in the oil and gas ecosystem Decoding the O&G downturn

8 minute read

23 April 2019

The past five years of low and volatile oil prices have shaken the entire O&G industry. From corporate strategies, operational performance, financial results, to even innovation and talent, companies are exploring new ways to adjust to the new normal.

After a difficult 2015 and 2016, the oil and gas (O&G) industry began showing signs of coming out of the woods by mid-2018, with oil prices recovering to US$85/bbl (Brent). Many industry executives appeared to regain confidence as their companies’ financials improved, resulting in growing optimism about 2019.1

Learn more

Create custom PDF or download the full report

Read all articles in the series—Decoding the O&G downturn

Browse the Oil, Gas & Chemicals collection

Read an article featuring these insights from Rigzone

Read an interview with Deloitte’s Andrew Slaughter

Read an article on this report from Oil & Gas Journal

Subscribe to receive related content

But then, oil prices surprised everyone by sliding more than 35 percent (Brent) to US$50/bbl in the last quarter of 2018.2 If fears of oversupply and the three largest oil producers (Russia, Saudi Arabia, and the United States) competing for market share weren’t enough, the rise in geopolitical tensions and concerns of a global economic slowdown seemed to have dented the positive momentum built over the past 12–18 months in the oil market. Although the downward slide has now been halted by the November agreement between OPEC and its allies to curb supplies by 1.2 million barrels per day (MMbbl/d), the steep fall amid heightened volatility marks five years of the collapse in oil prices from above US$100/bbl levels in 2014.3

How have O&G companies navigated the past five years of the downturn? Did the operational and capital adjustments of O&G companies translate into returns for investors? How have margins and value migrated between O&G segments? Which segment saw the highest fundamental–market divergence? Answering such questions could be essential to gain a complete perspective of the health and prospects of the O&G value chain.

Although many industry pundits have provided piecemeal perspectives across the phases of the downturn and recovery, a consolidated analysis of the past five years and a complete perspective covering the entire O&G value chain could help stakeholders—from executive to investor—make informed decisions for the uncertain future.

With this in mind, Deloitte analyzed 843 listed O&G companies worldwide across the four O&G segments (upstream, oilfield services, midstream, and refining & marketing) in an effort to gain a deeper and broader understanding of the industry. The ensuing research yielded a six-part series, Decoding the O&G downturn, which sets out to provide a big-picture reflection of the downturn and share our perspectives for consideration on the future.

In part one of the series, we explore the overall O&G industry—its market dynamics, the health of its segments, regional performance, and innovation and talent.

Underperformance or divergence?

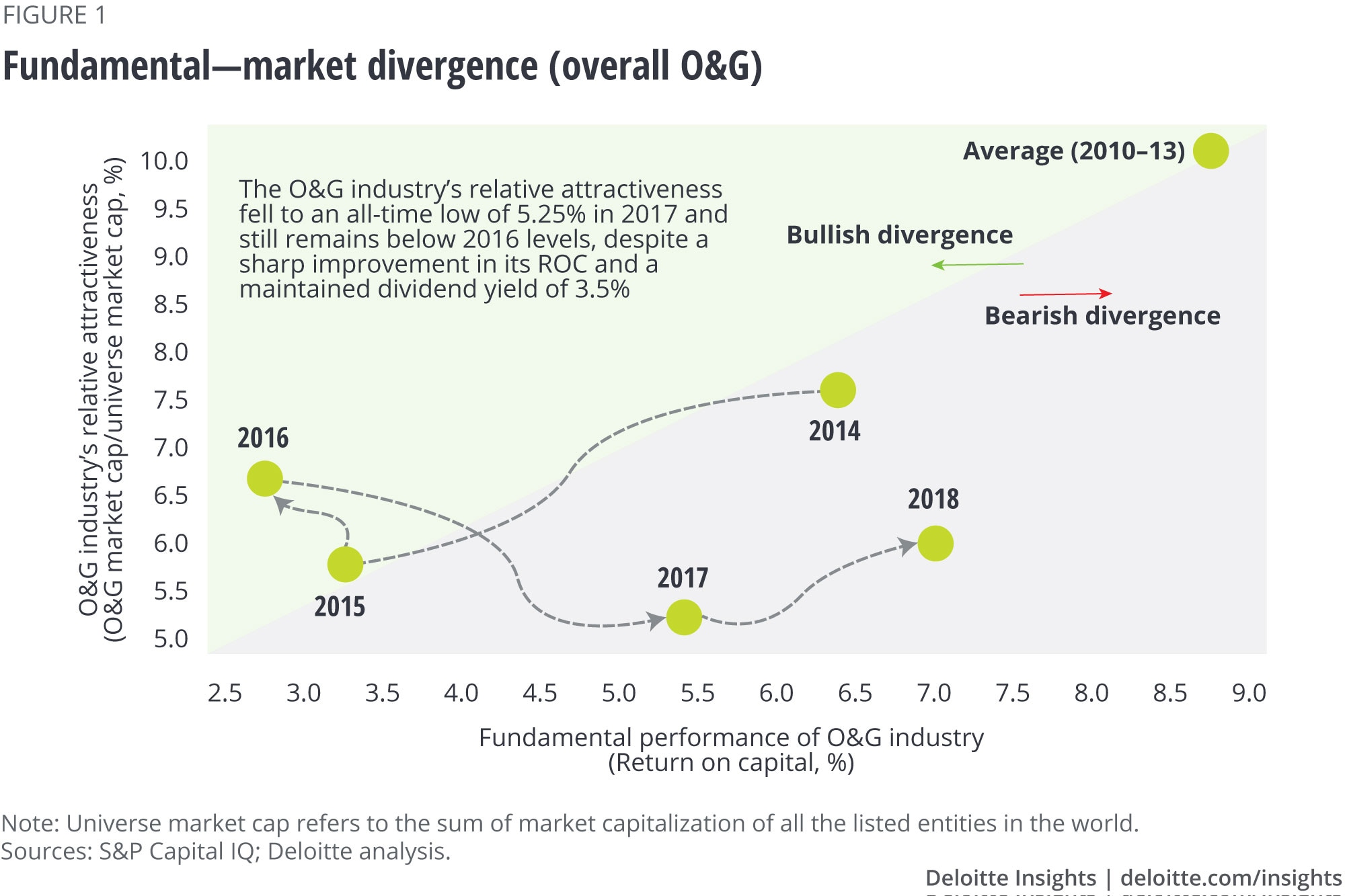

In the pre-downturn period (2010–2013), the O&G industry commanded roughly 10 percent of listed companies’ market capitalization worldwide at around US$5 trillion (figure 1).4 By the end of 2018, this figure fell to 6 percent, with only two O&G companies in the top 25 companies of the world by market capitalization.5 The fall in the industry’s attractiveness has come at a time when the global economy expanded by 23 percent to US$70 trillion over the past five years.6

Undoubtedly, this reduced attractiveness of the industry is likely because of lower and volatile oil prices and weaker financials of O&G companies. However, the market seems to have disregarded recent efforts of O&G companies to drive capital efficiency in their projects and overall financials. For example, the industry’s return on capital, which hit lows of 2.7 percent in 2016, has recovered fast and is today close to pre-downturn levels even in a sub-US$65/bbl price environment (6.9 percent in 2018 as against 7.3 percent in 2013).7

Likewise, there has been far less appreciation of the fact that the industry maintained its higher-than-average dividend yield of 3.5 percent (as against 2.4 percent of other industries worldwide) even during the past five years of the downturn. The O&G industry returned more than US$720 billion in dividends between 2014 and 2018, the second highest after the financial services industry.8 In addition, share buyback programs also transferred cash to shareholders.

Although the market’s expectation of sustained weakness in oil prices could explain this bearish divergence, the industry’s continued emphasis on operational performance, shareholder distributions, and free cash flows should not be ignored for long—it has the potential to help it to win back investors’ trust in the times to come. In fact, the industry is estimated to generate more free cash flow in 2018 than it did in 2013 when a barrel of crude traded at an average of US$112/bbl.9

Which O&G segments have driven this divergence?

Imbalance within the O&G ecosystem …

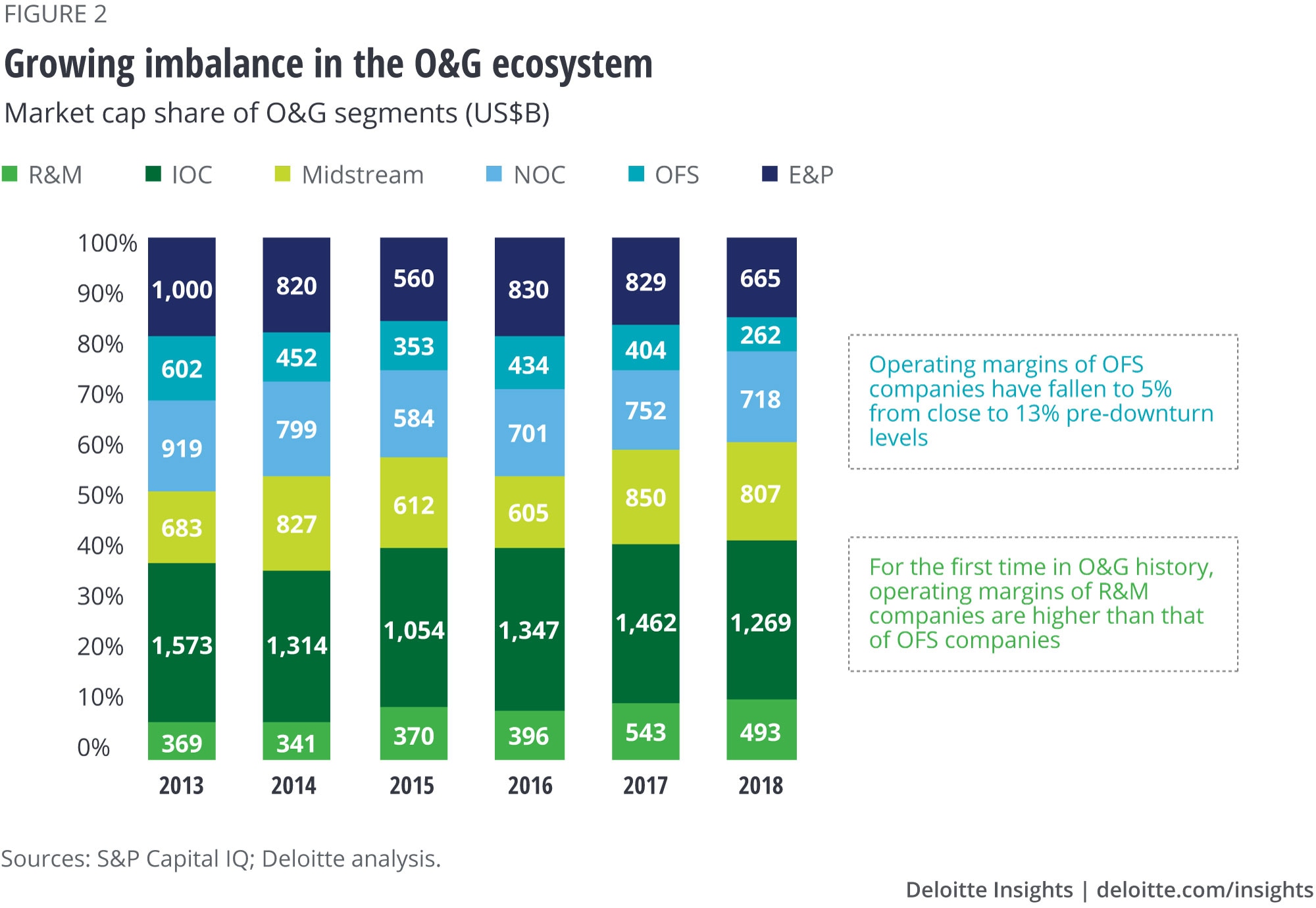

A fit-for-future O&G industry needs a healthy ecosystem of producers, service providers, shippers, and processors and marketers. Without it, the gains of a recovery would likely go to a select few, while losses from a downturn could affect many, potentially impairing the ability of certain segments to attract capital and grow sustainably. While it’s normal for value and margins to migrate across the ecosystem, especially in a downturn, the migration in this downturn has been highly skewed and unhealthy for the most part. And this has been our big worry related to this downturn.

Although producers are recovering, and in some cases growing again, many in the oilfield services (OFS) segment continue to struggle for survival. For example, market capitalization of the OFS segment, which is the backbone for both shale growth and offshore revival, has fallen by half to US$262 billion and the entire segment is now less than the size of the biggest supermajor.10 In fact, currently, only one OFS company figures in the list of top 25 O&G companies worldwide by market capitalization (figure 2).

Conversely, operating margins in what have historically been the least lucrative O&G businesses, downstream and midstream, have shot up higher than what an average integrated producer and service company makes. For example, downstream margins of 6 percent are now higher than the 5 percent margins of a service company. Similarly, a midstream company’s fees/spread per unit of volume transferred has remained flat at a minimum, while the underlying commodity’s price has fallen by more than 50 percent during the downturn.11

Today’s lopsided producer–contractor–customer relationship, or the health of the O&G ecosystem, means that stabilization in the industry may still be a few years away, or that a big rationalization could play out.

… with a high regional variability in valuations

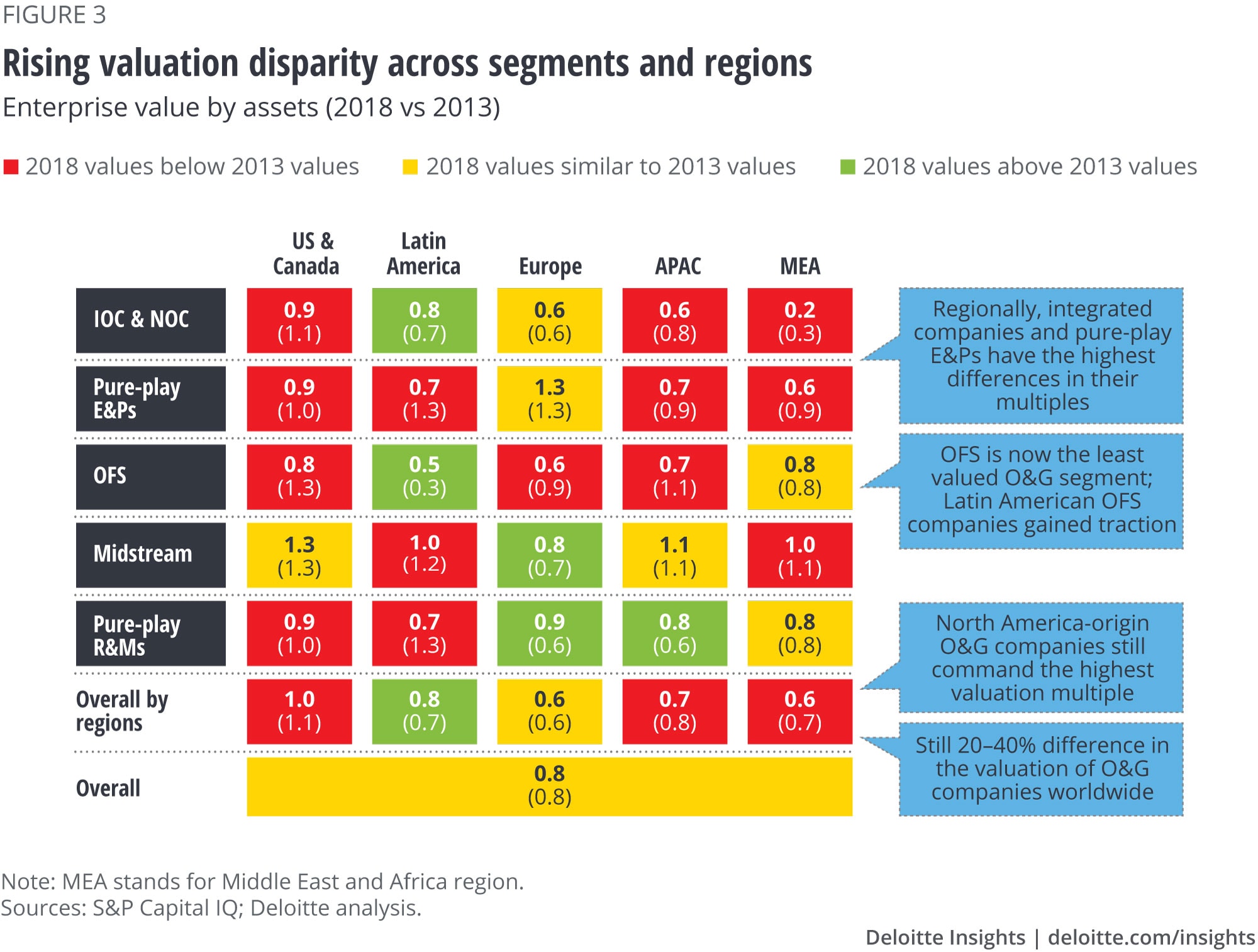

Unlike earnings, which have remained highly variable, the more stable, tangible assets provide a clearer picture of the industry’s performance and attractiveness. The industry has remained undervalued in general, with the market valuing O&G companies significantly below their book value or replacement cost at around 0.8 times (enterprise value/total assets, see figure 3).

At a regional level, however, EV/asset multiples have varied significantly despite O&G being a commoditized industry. In fact, there is 20–40 percent divergence in the valuation of companies/segments by regions. Although North America-based O&G companies have seen a fall of 10 percent in their valuation multiple, investors still generally value them close to their replacement cost. On the other hand, Latin American and European O&G companies have largely seen a flat to positive change in their valuations over 2013 levels.

Similarly, most private integrated oil companies (IOCs) and state-owned national oil companies (NOCs), especially outside North America, have received much lower valuation despite their stable integrated and/or diversified structure. On the other hand, OFS has turned into the least valued O&G segment, while the multiple of downstream companies worldwide hasn’t expanded like their margins over the past few years.

One can conclude that investors don’t seem to be buying into the O&G industry just to play price and margin cycles in pure-play businesses/regions or to park money in the safety of integrated structures. Although company-specific strategies and results that provide an upside beyond simple oil price increase could dictate investors’ interest, such high differences in valuations in an improved macro and oil price environment could set the stage for mega- and cross-regional M&A in the O&G industry.

Employment and innovation have somewhat resisted the downturn

The fall and heightened volatility in oil prices have troubled many executives, upset investors, and led to unforeseen migration of value and margins within the O&G industry. But what has been the impact of this downturn on innovation and the workforce in the industry? Did the downturn, along with automation, affect hiring in the industry? Did O&G companies favor a manufacturing and mass production mindset over technology- and data-led optimization?

Although the industry’s overall employment levels fell during the downturn, 2017 saw a recovery in headcount, and the current employment numbers of 4.5 million are only 1 percent below the 2013 numbers. The reason: About 300,000 layoffs in oilfield services, pure-play E&Ps, and private IOCs were largely offset by a hiring of 255,000 employees by NOCs and pure-play midstream and downstream companies (figure 4). Although redistribution of jobs between the segments/regions accelerated, especially those that are analytics-based, the industry’s volume growth and innovation seem to have supported overall employment by creating new and more work profiles.12

Similarly, the 16 percent fall in the industry’s research and development (R&D) expenditure to US$13.5 billion has been much less than its curtailment of capital expenditure. Impressively, the hardest-hit OFS segment maintained its R&D spending of US$3.4 billion and downstream registered its highest R&D spend in 2017. On the other hand, surprisingly, most large IOCs and NOCs have reduced their absolute R&D spend despite the established role of technology in lowering breakevens during the downturn. Although internally generated innovation is generally considered important, a balanced and united focus on innovation is also critical as organizations must often complement their internal innovation capabilities with solutions, ideas, and technologies from external partners and vendors.13

Lessons from the downturn

The lower-for-longer environment seems to have shaped the industry in its own unique way, and is likely to continue to do so in the near future. Although company-specific strategies that provide an upside beyond oil price and generate sustainable efficiencies will often determine investors’ interest, a few pointers could help the industry to respond favorably to the new reality:

- O&G companies with fit-for-future portfolios should effectively position themselves as a strong value/yield investment and strongly talk about their progress in growing free cash flows, maintaining shareholder distributions, and increasing their ROC to investors.14

- Advantaged segments and players should bring a balance to today’s lopsided contractual relationships by sharing in the economics of efficiencies created by contractors and vendors, thus providing a win–win relationship.

- O&G companies across the value chain should stay invested in harnessing capabilities of the new-age workforce and remain open to accelerated innovation happening outside the industry as well.

Volatility has always been the name of the game in the O&G industry. However, the past five years have forced many companies to rethink their strategies. A strong understanding of the downturn could therefore help companies determine where to play and how to win. In the next few articles, we will examine all O&G segments through the lens of the downturn. Explore the entire Decoding the O&G downturn series to understand how you can thrive amid uncertainty.

© 2021. See Terms of Use for more information.

More insights for Oil, Gas & Chemicals

-

From bytes to barrels Article7 years ago

-

Refining at risk Article7 years ago

-

Following the capital trail in oil and gas Article10 years ago

-

A renaissance in the domestic oil and gas industry Article11 years ago

-

Global renewable energy trends Article6 years ago