Individuals and their connections are the key to innovation

The DIB is a people industry. A few companies may have solutions or technologies that others cannot match, but for the vast majority—even the largest companies—maintaining a competitive edge depends on talent. A skilled and diverse workforce is more likely to innovate, and an experienced workforce is more likely to deliver results on time.8 As a result, competition for skilled, experienced talent in the DIB can be intense.

Success in the DIB, then, rests on access to talent. But access to talent is yet another people problem. A job seeker may scour the web and various job posting websites to find the right job, but the sheer number of job postings and job seekers can render ineffectual the effort to connect the right talent to the right job. In other words, a typical job seeker will struggle to find the right opportunity unless they have a connection that helps them even know where to look, and a company cannot find talent unless they know where to look for that talent.

Both of these problems rest on relationships.

Job seekers need relationships to find the right positions, and companies need the right relationships to find the candidates they need. The health and innovativeness of the DIB as an industry depend on both companies and individuals creating those relationships as efficiently as possible. In some sense, innovation depends on networking.

Some of the most studied innovation hubs in the world such as Silicon Valley or Boston-Cambridge first appeared because the right mix of people was brought into close proximity and allowed to make social connections.9 Fostering connections between government, companies, and talent is one major factor in creating an innovative DIB.

Here we can turn to a real-world case study to see these forces in action. Huntsville, Alabama, is a positive outlier in networking culture and business collaboration. Business leaders almost universally reported to us that they found their peers to be open and interested in networking, even in cases where they might be competitors on another deal.

The results of this culture are clear to see in the growth and productivity of the industry in the Huntsville areas. Madison County, where Huntsville is located, ranks seventh among all US counties for defense contract spending.10 That demand, along with additional work from NASA and the research universities in the area, has created a rich innovation ecosystem. In fact, Huntsville has the highest number of engineers per capita in the United States.11 And the economic benefit of this relationship-based innovation ecosystem is evident. Huntsville is on par with or better than national averages across education, income to mortgage ratios, per-capita household income across races, unemployment rates across races, and the percentage of minority groups below the poverty line.12

But even in the positive environment of Huntsville there are problems that limit the diversity, and therefore, innovativeness of the DIB. For example, while Huntsville’s rates of business ownership by minorities and women are better than national averages, they are still below representation. Minorities make up 34% of Huntsville’s metro population, yet account for only 27% of business owners. While that number is above the national average of 18%, Huntsville also has a larger minority population than the national average, meaning that there is actually a larger gap in representation of minority business owners in Huntsville than in the nation as a whole.13 Women, similarly, are 51% of the population and 47% of the labor force in Huntsville, but only 44% of business owners. The true number for solely women-owned businesses (i.e., not owned jointly with a man) is likely even lower—in the high-20% range.14

These statistics do not mean that Huntsville is not paying attention to diversity. In fact, quite the opposite, Huntsville is doing better than the national average on many of these measures. But that is exactly why these continued disparities are so striking: In some ways, Huntsville is a positive outlier, yet even it suffers from the exact same lack of diversity as the rest of the country. If this lack of diversity is not due to inattention or lack of interest, then it must stem from more difficult, structural factors about how the industry itself operates. This is particularly striking because the same challenges with diversity that appear in Huntsville occur at the national level as well. For example, the mid-20% range for sole female business ownership in Huntsville is also consistent with estimates of female executives in the entire aerospace and defense industry, estimated at between 19%–25%.15 For other minority groups, representation can be even lower among executive ranks: It is estimated that Black or African Americans make up only 5% and Latinos a mere 4% of executives in aerospace and defense.16

These are more than just interesting statistics; they have a real impact on performance and on lives. For companies, research from numerous industries shows that greater diversity in workforce and leadership lead to increased revenue and corporate performance. For example, manufacturing companies that increased their representation of women in leadership by 30 percentage points, saw a 15% increase in corporate revenue.17 That boost in revenue can also be a boon to local communities. Black or African Americans in Huntsville have nearly double the rate of unemployment of white residents, and Latinos see roughly half the average household wage.18 So increases in employment in high-paying industries such as the DIB can be a significant economic benefit to these communities.

But above all, greater diversity in the DIB is about mission. The DIB is not just any industry. It exists to help the country prevent and win wars. To do that, it needs the most innovative people and the most innovative companies. Research continually shows that innovation comes from combining diverse sets of ideas, and that diverse companies produce innovations at a higher rate.19 People from diverse backgrounds bring diverse sets of experience with them, exactly what is needed to address complex problems. A lack of diversity in the DIB is leaving innovation on the table at a time when it is critically needed.

“Network equals net worth”

To find the root of these challenges with diversity, we first need to understand what makes companies successful in the DIB. Companies and individuals are both more likely to succeed if they have significant social capital—that is, the set of relationships with customers, partners, and others.20 Those relationships provide better knowledge of what opportunities exist, what customers are looking for in certain bids, what technology solutions are emerging, and where to find the right talent for particular tasks.21 And those connections are important to the DIB itself: They help create efficiency in the industry and provide assurances that those selected for a job can deliver as promised.

But these densely connected networks can also make it difficult for newcomers to break into the industry. Without something of value to trade—whether that be a new technology or the owner’s personal relationships—new entrants, whether companies or individuals, will likely find themselves relegated to junior partnership roles that hinder their long-term growth.22 The problem for the DIB is that these things of value are not uniformly distributed. Certain populations have greater access to things that the DIB values, making it easier for them to enter the industry. For example, retired military officers may often have existing personal relationships with clients and be able to speak their language, making them more attractive hires than nonveterans. Individually, these decisions are rational and good for each company and individual, but if every company follows suit, it can unintentionally create a more homogenous workforce than desired, effectively making it more difficult to get diverse perspectives.

To be successful, new entrants trying to break into the DIB, whether as individuals looking for jobs or companies looking for work, need to find something the wider network values. The challenge is that the individuals in that wider network tend to gravitate toward those like themselves. Many of us are naturally more comfortable with those like ourselves, who share similar backgrounds, hobbies, ways of talking, and so on. Research on everything from hiring decisions to business partnership formation show that these ties of sameness, called homophily, play an important if subconscious role in many business decisions.23

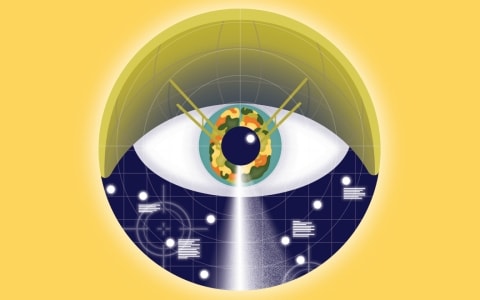

How much companies/individuals seek sameness is variable. The more homophily in a network, the harder it will be for underrepresented minorities to break into the main network and be successful.24 This phenomenon has been seen in everything from collaborations to academic citations, so it is no surprise when we see it in Huntsville’s DIB ecosystem as well. Take subcontracting relationships for example. With the major defense contractors being so large and dominant in the industry, subcontracting can be a key lifeline for small businesses. When examining the subcontracting relationships for the largest 12 defense contractors in Huntsville, we find that, while minority-owned companies make up 29% of businesses in our sample (on par with the 27% of all businesses in Huntsville that are minority owned), they received only 8% of all subcontracts and 4% of all subcontracting dollars awarded.25 By graphing these relationships, we can also see how many minority-owned companies exist—almost literally—at the edges of the business ecosystem, struggling to break in (figure 1).