National security readiness How data can improve national security crisis response

13 minute read

13 June 2019

Elaine Duke United States

Elaine Duke United States Matt Gentile United States

Matt Gentile United States Joe Mariani United States

Joe Mariani United States Mark Freedman United States

Mark Freedman United States

National security organizations need to be ready to respond to all types of crises, whether natural or man-made. How can data help them be truly ready?

Sun Tzu, one of history’s military strategists said, “The art of war teaches us to rely not on the likelihood of the enemy's not coming, but on our own readiness to receive him.”1 Indeed, for centuries, readiness has been a key requirement of militaries around the world. But today, we live in an increasingly complex world where not just the military but a variety of departments and agencies across government must be ready to respond to crises.

Learn more

Read more from the Aerospace & defense collection

Subscribe to receive related content from Deloitte Insights

Take, for example, a large-scale attack on a major US city. In the minutes, hours, and days that follow the blast, the Departments of Homeland Security (DHS), State, and Justice, the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), the Central Intelligence Agency, and others would jump into action to secure the scene, communicate warnings to the public, track down and arrest the culprits, make requests of foreign allies, comb through intelligence, and prevent follow-on attacks.

These national security organizations would need to effectively coordinate with each other, deploying and calling upon thousands of personnel and assets in a dynamic and dangerous situation. In many cases, these agencies would coordinate but not command, collecting information from hundreds of sources and distributing it to the right stakeholders. Each of them having pressing questions: What search and rescue capabilities are available near the scene of the incident? Which federal law enforcement assets can be deployed immediately, and how best can they communicate and coordinate with local police? What databases might have information relevant to the attackers and the victims? Who are the best contacts in foreign governments to consult on the international response to the attack?

These are important questions for national security organizations to answer during a crisis, yet execution can be surprisingly challenging. However, a few simple steps using technology can help connect national security organizations, providing a unified picture from top to bottom that can describe if the organization is truly ready.

Are national security organizations ready?

Even during regular operations, some national security organizations can struggle to see a unified picture of all of their assets and activities. For example, Customs & Border Protection (CBP) and the Coast Guard might both spot a vessel at sea with all the hallmarks of a narcotics smuggling operation. DHS leadership, however, may not be able to see that CBP’s helicopter is close enough to monitor the vessel until a Coast Guard ship arrives for interdiction. That can lead to obstacles in decision-making during a fast-moving operation, and unnecessary danger for forward personnel.

These specific examples can help focus the questions: What are the specific capabilities needed to respond to a terrorist attack in a specific place? Who is within range to interdict a vessel? When the questions become more abstract—are we ready to respond to every threat to the United States?—the difficulty increases exponentially. National security organizations face a daunting set of requirements: to be prepared for crises, natural and man-made, intentional and accidental, physical and cyber, in all their dimensions. Against a backdrop of proliferating threats and increasing demands on the US government to leverage every dollar in the budget, it’s time to ask, how can national security organizations be truly ready?

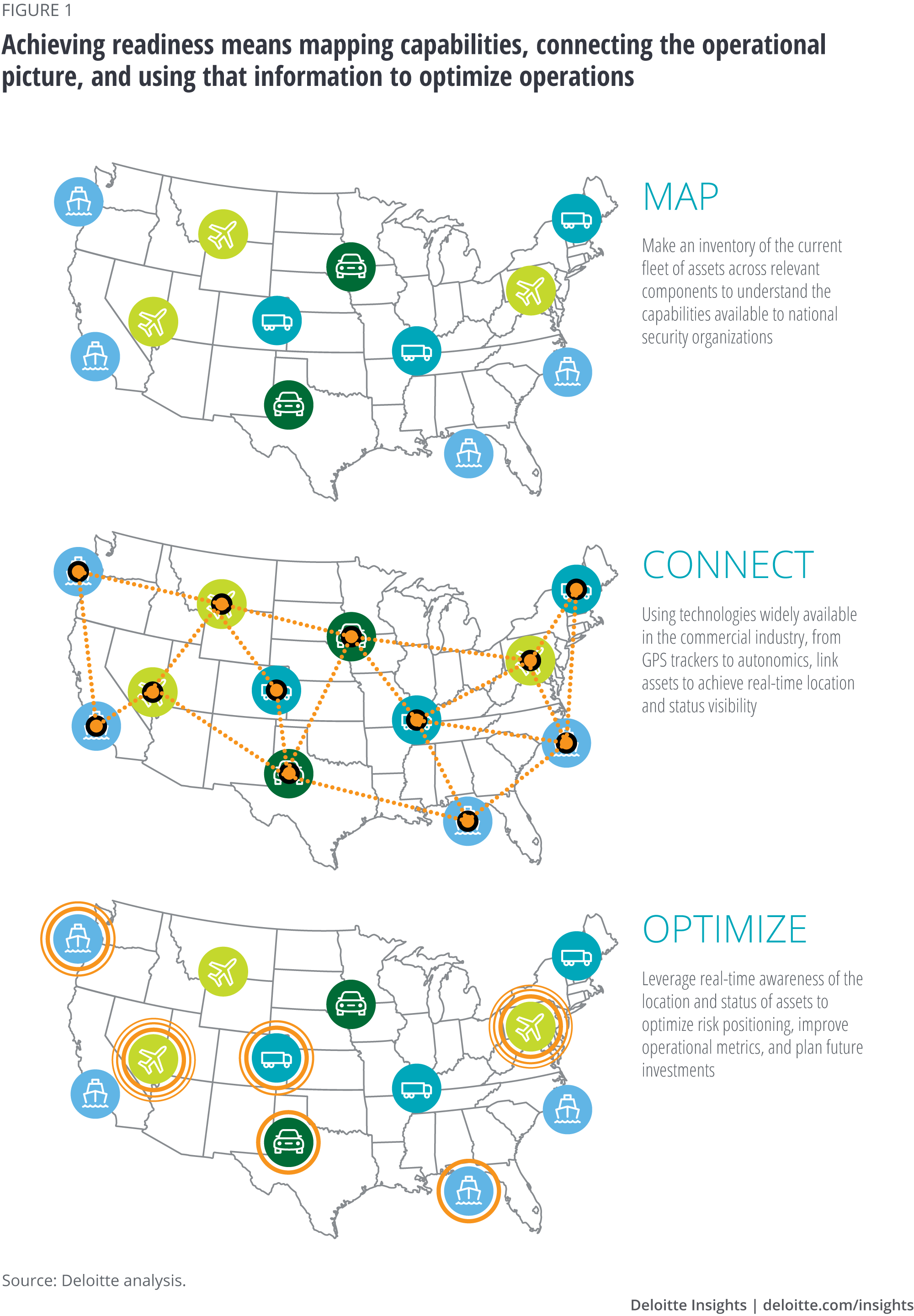

One possible answer is that national security organizations could benefit from a better, more cohesive understanding of their own capabilities—that is, how they can leverage the capabilities of each of their constituent parts (component organizations of DHS, embassies of the State Department, field offices of the FBI, and so on), as well as the assets that enable them. To ensure readiness across the national security enterprise, departments and agencies should develop an adequate system for answering what their capabilities are today, where they should spend the next dollar to improve them, and how to deploy them optimally. That means they should map their assets—what and where they are, and what their status is—and connect that data across the organization. Then, the components, bureaus, posts, or offices that own or operate the assets can gain the insight needed to optimize performance and investment, allowing national security organizations to improve their overall crisis response (see figure 1). As national security organizations gain a deeper and broader picture of their own capabilities, they can improve readiness for the risks that might arise.

Mapping the assets

For national security organizations, being ready for risk starts with knowing their own capabilities, which translates to having a real-time, ground-truth picture of subordinate and component assets, and when needed, the assets of other partners and critical enablers. Without understanding what assets exist and are available to address a threat, national security leaders could struggle to obtain a unified readiness picture. The national security community’s capabilities flow from three critical assets—equipment, personnel, and infrastructure. In the case of DHS, each of these are managed by suborganizations operating semi-independently, with DHS headquarters providing departmental coordination. Other national security organizations, even if they have direct command over their subordinate organizations, likely still lack the ability to see an up-to-date and actionable unified picture of the assets at their disposal.

Operational equipment, personnel, and infrastructure are spread across the United States and globally, housed under multiple organizations with distinct needs and missions. However, they still need to be deployed or employed when tasked by leadership, and during a complex crisis, this must happen rapidly and in coordination. For this to happen, national security leaders need an appropriate view of readiness, risk, and operations, while each component or subordinate organization within their departments and agencies must understand its own position in the larger picture. The challenge is in developing an asset management system that brings a picture of these capabilities together for decision-makers, while maintaining flexibility and delegated authorities for fast action.

This may seem almost impossible to implement—just finding the location of all of a department or agency’s assets is a big enough challenge, and understanding their status often means reporting up and down the chain. But mapping technologies that track asset location and status are already at work in many commercial companies today. Real-time data streams taken from real-world assets allow shipping companies to track their fleets, manufacturers to map their production lines, and consumers to follow their food delivery orders via an app.2 These technologies turn every employee check-in, every rotation of a connected turbine, and every scan of a product or package into data that contributes to an overall picture of activity and performance. To improve their own readiness, national security organizations should begin by moving beyond a reporting model in which components, bureaus, posts, offices, and other sub-units report their status up and down the chain to a more dynamic, granular, data-driven map of organizational capabilities.

Connecting assets and organizations

Building a map of capabilities is just a first step. To create a real-world, real-time picture of the location and status of personnel, equipment, and infrastructure, organizations should connect their assets. In practice, that means deploying and leveraging smart technologies to each asset class throughout component or subordinate organizations within national security departments and agencies:

Equipment. When responding to a crisis, national security organizations often need to quickly identify equipment that may be housed across a range of offices or components and surge it in a coordinated and effective way. For example, when the FBI is called to the scene of a crisis, it’s not enough to know which helicopters are nearest to the situation—it’s also critical to know if they’re ready to fly and if pilots are available. The special agent in charge at the local field office would want to see not only what relevant equipment she has at her disposal in-house, but also what is at the nearest adjacent field office, what can be pulled in from other field offices, and what needs to be surged from headquarters. Sensors are widely deployed in many industrial systems, aircraft, ships, and vehicles. By combining sensor data with the location of the equipment in a common data platform, leaders can see a more detailed and accurate picture of assets’ availability and maintenance status, enabling smoother crisis decision-making.

Personnel. Many national security organizations, such as the State Department, employ rotating workforces. For example, foreign service officers usually spend two years at an embassy before moving on to a different assignment. This system is ideal for building a well-rounded workforce that benefits from a diversity of experiences. But without skills-based personnel management tools, it can become easy to lose track of which employees may have valuable expertise from previous assignments that could be relevant to a crisis today. Creating these tools is often the first step to making available detailed information about what each worker can do, so that it’s easy for leadership to find the best experts across a global workforce in a time of crisis.3 Equipping personnel in the field with wearables and apps can enhance their awareness of key developments and allow them to make more informed decisions and connect with other parts of the organization across different time zones. Technologies such as augmented reality can extend this data advantage even further by allowing the perfect expert for any situation to be virtually present. For example, some airlines are already using augmented reality to connect maintenance personnel at small airports with experts so that they can make complicated fixes immediately instead of waiting for the experts to fly in, which can create costly delays.4

Infrastructure. DHS is responsible for monitoring the infrastructure that enables our safety, so real-time knowledge of the status of critical infrastructure can be just as vital as having the right equipment and the right people. Just as knowing what equipment is at your disposal and how to quickly get ahold of the right expert can be critical to emergency response, it is also important to have a full picture of the infrastructure required to make that response successful. That includes knowing which refueling depots are operational, which ports can handle incoming shipments, and which nearby airfields can be made available for unexpected air traffic. Smart sensors embedded in infrastructure, ranging from ports to tarmacs, can provide this information.

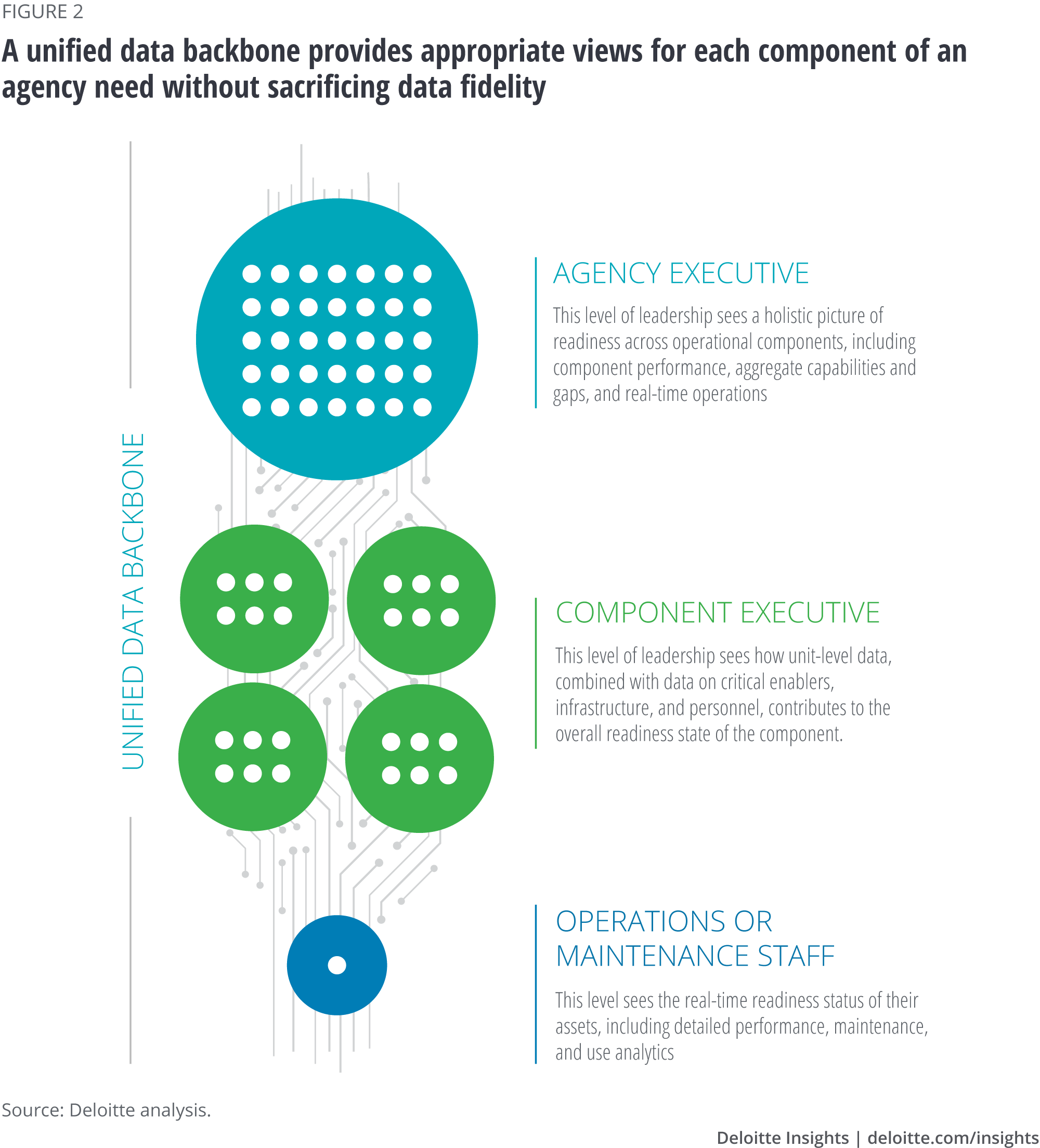

Simply gathering this data is not the end, however—it has to be put to use. Connecting means incorporating smart technologies into a mapping plan, but it also means connecting the data generated by those streams to a single digital backbone that spans headquarters as well as subordinate or component organizations (see figure 2). The digital backbone stores the data in an accessible way, so that it can be analyzed across an entire national security organization to gain real insight. Then, it allows both the local mechanic and the DHS secretary, the foreign service officer and the secretary of state, the local special agent and the FBI director to see a readiness picture derived from the same data streams. The mechanic can see the flight readiness of an aircraft, and the DHS secretary can view emergency response capability readiness—enabling all involved to make real-time decisions across the organization.

This access to the data allows leaders to zoom in and out, encountering both the granularity and the broad, emergent trends of their readiness posture. It allows each constituent part of the organization to work toward greater excellence within its specified mission sets, and when needed, to operate in a coordinated way across the broader department. With that knowledge, leaders can take the right action to optimize performance in the real world.

Optimizing for readiness

Mapping and connecting assets enables leaders to start asking the right questions. By combining the real-world and real-time pictures of all their assets, decision-makers can create what is essentially a “digital twin” of the agency and its components.5 This digital, data-driven picture of the organization allows leaders to conduct detailed scenario planning. They can test the agency in different types of crises and operations that would be impossible to recreate in real life. Moreover, by seeing how the agency performs in these various contingencies, planners can understand where gaps in capability exist and where the next dollar of investment should be spent to best fill those capability gaps—whether through additional capacity, more advanced training, or new assets.

To understand if a national security organization is truly ready, decision-makers need to understand core readiness questions:

What capabilities are needed to meet the risk? What are the capabilities, assets, and enablers that allow national security organizations to execute their missions? This is the starting point for readiness, and understanding the mission, along with all potential mission conditions, is paramount.

Are those capabilities ready for action? What is the current state of the personnel, capabilities, and supporting infrastructure needed to meet the risk? This measures how close the assets that the organizations can call upon are to the needed capabilities.

Where should the next dollar go? How should a national security organization invest to achieve the greatest impact? In the case of DHS, this is a particularly acute challenge as its component organizations vary widely in their purpose, capabilities, and readiness needs. The components should focus on achieving their own optimal outcomes—how they can be most ready for their unique mission sets. But at the leadership level, DHS coordinates, but does not own, many assets critical to emergency response. Therefore, the data from connected assets, personnel, and infrastructure can help DHS make key decisions on how to improve readiness at all echelons, from component-level budgets all the way down to individual aircraft.6

The unified data backbone depicted in figure 2 can help national security organizations answer these questions, allowing the operational components and subordinate organizations to optimize their own organizations, while connecting to headquarters for global coordination.

Deploying readiness

How can national security organizations begin to implement this approach to readiness? The critical insight is that smart technologies, connectivity, and data are only as useful as the organization allows—it’s the people who must make them work. Therefore, it is important that leaders think about the organization holistically when implementing the technology solution. And that can be especially challenging in large agencies, which have a number of complicating organizational factors:

- Unique legacy systems across dozens of components, bureaus, posts, offices, etc.;

- Limited insight into assets and personnel across subordinate units;

- Existing, but not fully integrated, data sources; and

- Reliance on vital partners across the interagency to execute operations, but limited ability to mandate or direct action.7

But readiness is still achievable. Not only are many of the core technologies already proven in the commercial world, national security organizations likely have much of the needed data already. In fact, some parts of the US government are already leveraging data on hand to implement readiness in areas such as maintenance and operations. The US Air Force recently began using data that had been generated for years by C-5, C-130J, and B-1 aircraft to feed predictive maintenance algorithms.8 The same approach can be used for data that other agencies already capture, from airports to embassies to intelligence fusion centers. All this data has a value, and tapping that value can be key to achieving a new level of readiness. (To read more about how the Internet of Things and predictive maintenance are already helping organizations, check out Making maintenance smarter.)9

Naturally, any transformation of a large bureaucracy can be challenging. However, hard-won lessons from other government and commercial modernization efforts can help smooth the transition to a real-world, real-time readiness picture.10 In fact, national security organizations can turn many of their organizational challenges into advantages as they deploy readiness solutions. While commercial businesses often must integrate new technologies into their core operations with consequences that potentially affect the entire organization, US government departments and agencies can target, compartmentalize, and iterate without risking the mission. Here’s how they can begin:

Understand the possibilities

A basic understanding of the technology frontier is vital. That usually involves immersing organizations in an ecosystem of innovation, to bring leaders at every level up to speed on the latest technology developments and relevant applications. That also involves some catching up on industry developments: Just as you can track the location of an Uber or a pizza delivery, and UPS can track the location of its entire fleet, DHS should be able to track the location of its mobile assets. And it involves meeting industry at the frontier, such as learning the applications of artificial intelligence to autonomics.

Build a proof of concept

While the impact of a new approach to readiness can be transformation, that transformation does not need to take place overnight. In fact, beginning with small pilot projects can expose what works and what doesn’t, increasing the overall project’s chances of success. Take the example of a leading heavy equipment manufacturer that wanted to create a “smart factory” with visibility into where all its products were in the assembly process.11 Rather than leaping in with a large up-front investment, the company began small, adding sensors to only one production line at first. Doing so allowed it to identify and fix technical hiccups with communication and see the real benefits the project could create. Armed with that real-world ROI, the manufacturer was able to confidently scale up the project to other parts of the factory. For the State Department, this might mean starting with team-level innovations within a particular embassy before expanding solutions across the entire organization.

Iterate and scale

After piloting one or two solutions, take stock of lessons learned.12 Pilots do not need to be perfect before iterating on successes. Even small changes can add great value. For example, even if it’s daunting to tackle live autonomics data, ensuring that all aircraft across the emergency response enterprise are always streaming standardized location data provides substantial benefit at limited cost, and simply providing relevant stakeholders access to location data can prove extremely valuable during an emergency.

Don’t forget about partnerships

National security organizations often rely on partners across the interagency, in the private sector, not-for-profits, foreign governments, and state and local organizations in almost every domain. Mapping those relationships, understanding their capabilities, and incorporating them into planning can improve the fidelity of a data-driven picture of an agency’s operations. National security organizations should start small, with targeted pilots with select partners, and test outcomes during routine operations and exercises before deploying the solution in a crisis.

In the end, national security organizations are not expected to make leaps using technology alone. Progress will likely depend on how people deploy technologies to forward the mission, how each sub-component within an organization leverages data in its operations, and how national security leaders integrate these innovations into a holistic picture of capabilities.13 And there are predictable obstacles along the way. A Deloitte survey shows that finding talent, breaking down silos, strengthening cybersecurity, and getting strong sponsorship from leaders are all key challenges. But they’re challenges that many organizations have already overcome. Armed with a few key principles, decision-makers can implement a readiness plan to unleash the power of data across the national security enterprise. By using proven technologies in new configurations throughout an organization, leaders can gain a real-time, real-world picture of their capabilities and truly be ready for risk.

Explore the Government and public services collection

-

Government & Public Services Collection

-

Expecting digital twins Article6 years ago

-

The Reimagine Learning network: Tackling persistent problems Article5 years ago

-

The smart base Interactive6 years ago

-

Finding the right innovation Article5 years ago

-

Military readiness through AI Article5 years ago