The outcomes approach has become more popular in recent years, but it’s still relatively uncommon. Most programs still use metrics that focus on processes, tasks, and outputs (e.g., checks issued, referrals made, etc.), rather than the quality of engagement and tangible improvements in the lives of those they serve. Inflexible timescales and the pressure to accomplish more with fewer resources also make it hard to move from an output mindset.

In the United States, the state of Oregon uses data integration to more fully understand and compare the impact of its programs and services on children’s lives. The Oregon Child Integrated Dataset securely combines and analyzes data from five state agencies—the Department of Education, Early Learning Division, Department of Human Services, Oregon Health Authority, and Oregon Youth Authority—to identify opportunities to better support positive outcomes for children.19

Wales has a national outcomes framework that describes how it will measure improvements in care and support services. This framework considers personal outcomes, improving well-being by understanding what matters to people and what they want to achieve.20 For example, a person might want to find stable employment, regain their independence at home after a hospital stay, or reconnect with estranged parents.

By acknowledging people’s goals and aspirations and giving them some control over their care, providers can help them find the best path forward. Scotland’s Self-Directed Support program, for example, gives beneficiaries a budget to plan their own services as equal partners with social care staff.21

Agencies can also focus on outcomes in procurement and contracting. Rather than designing a contract that funds a specific number of workshops for domestic violence survivors, for instance, an outcomes-based approach would require a provider to show fewer repeat cases of domestic violence among its clients as a result of its work.

In the United States, Rhode Island’s Department of Children, Youth, and Families (DCYF) has made significant strides in outcomes-based contracting. In 2016, DCYF completed a procurement cycle that resulted in 116 new contracts organized around 15 outcome-based service categories tied to specific objectives. The contracts asked providers to propose programs to help children and families achieve specific outcomes; this flexibility allowed local experts and providers to offer ideas DCYF hadn’t considered before. Since this procurement cycle, DCYF has seen a 66% increase in its number of contracts with family-based foster homes and a 23% reduction in its share of foster children living in group settings.22

6. Focus resources on what works and based on feedback from clients and families

Social care agencies tend to capture data on problem areas, such as lost jobs, criminal convictions, homelessness, and hunger. They rarely seek data about what’s going well for individuals or communities. Little attention is paid, for example, to how many elderly people get to medical appointments with help from volunteer drivers, or how many previously unemployed people find stable, well-paying jobs. But a government that wants to improve people’s lives needs to understand community strengths.

Strengths-based data collection considers community assets and the positive aspects of people’s lives. Shifting the focus to “what’s right” can identify untapped or underused community resources and assets. It helps to nurture resilience rather than dependency.

In one strengths-based approach called asset-based community development (ABCD), social care agencies identify people with specific talents and resources and connect them with complementary needs. The idea is to build on strengths already in the community, focusing on what residents can do for one another. In the United Kingdom, for example, as part of the York City Council’s ABCD program, one resident who overcame serious health challenges now serves as a community health champion, arranging activities that foster relationships among people in her community.23

ABCD advocates point to five kinds of assets found in every community—people with skills and abilities; associations formed to achieve common purposes; institutions such as businesses, schools, and government organizations; physical assets such as land and the built environment; and connections among individuals. Programs based on ABCD harness these assets to improve the social determinants of health in their community, using social capital—the level of connectedness among residents—to drive changes that improve well-being for everyone.

In Whitesburg, Kentucky, for example, a community partnership called the Letcher County Culture Hub builds on local assets to improve community capacity and wealth based on a model called community cultural economic development.24 This group has helped start new local businesses and expand others; helped local artists, farmers, teachers, and others use their skills to generate revenue; and revived two local, moneymaking cultural institutions, a square dance, and a bluegrass festival.25

A social care system for today

Large-scale change often requires a watershed moment, one that forces us to acknowledge and accommodate a new world order. The Great Depression was one such example, giving rise to the New Deal. The September 11 terrorist attacks were another, transforming international air travel and national security. COVID-19 and its associated costs represent another such moment, one with the potential to reshape health and social care systems.

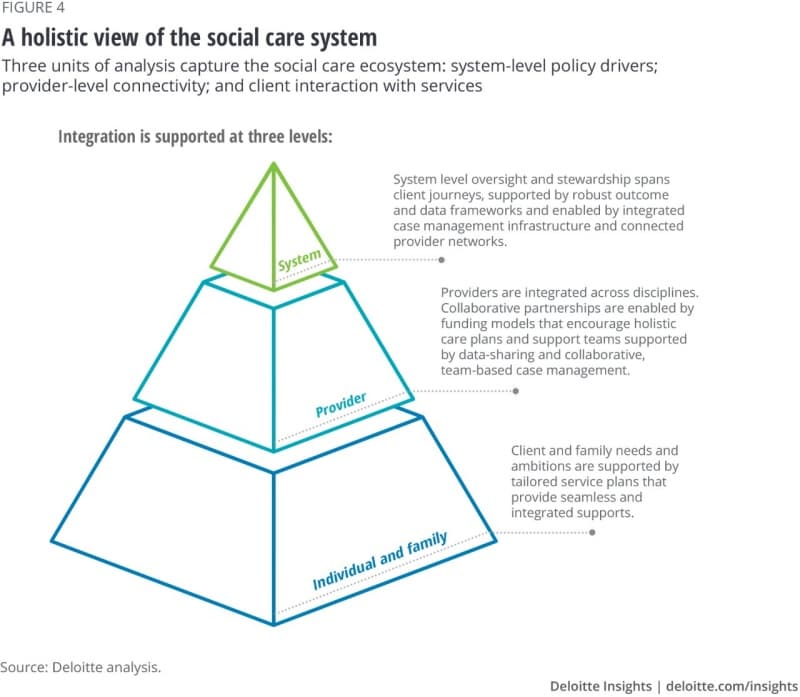

Various jurisdictions have advanced many of the concepts behind the new social care value chain, but it’s occurred in a piecemeal fashion. The new orthodoxies have yet to take root across all levels of the social care system (figure 4). When they do, here’s how a holistic ecosystem of care will take shape:

On the system level, the social care system will provide oversight and stewardship across the entire client journey, with support from robust outcomes-based data. Connected information systems will support integrated case management, collaboration among provider networks, and seamless care journeys.

On the provider level, agencies and provider partners will be integrated across disciplines, with funding models that enable collaborative partnerships. This model will encourage holistic care plans and care teams supported by data-sharing and case management systems.

On the client level, the system will tailor a unique care plan to fit the needs of each client.