Inclusive smart cities has been saved

Inclusive smart cities Delivering digital solutions for all

17 minute read

28 August 2019

Kathleen O’Dell United States

Kathleen O’Dell United States Adam Newman United States

Adam Newman United States Jenny Huang United States

Jenny Huang United States Nick Van Hollen United States

Nick Van Hollen United States

As inclusion becomes integral to urban centers, how can it be extended to smart city programs? And how can technology better enable inclusion across city services, public engagement, and economic opportunities?

Moving from technology-centric to citizen-centric smart cities

As urban populations grow increasingly diverse, many cities are turning to technology and smart city solutions to build more livable environments and improve the delivery of public services.1 These initiatives have the potential to expand access to city services, improve public engagement, and spur economic growth. However, smart city design and implementation shortcomings, coupled with the digital divide between different population segments, might unintentionally leave some communities behind. This is forcing cities to confront the question: How can digital solutions advance, rather than impede, inclusion?

This article explores the relationship between technological innovation and inclusion in today’s cities. Based on research, interviews, and engagement with city leaders around the world, we outline approaches that municipal governments can apply to make digital solutions more accessible and useful for their residents.

Prioritizing inclusion in urban development

inclusion

/ɪnˈkluːʒ(ə)n/

The idea that everyone should be able to use the same facilities, take part in the same activities, and enjoy the same experiences, including people who have a disability or other disadvantage.2

Learn more

Explore the Smart cities collection

Read more from the Government and public services collection

Subscribe to receive related content from Deloitte Insights

Download the Deloitte Insights and Dow Jones app

Today’s cities are larger and more diverse than ever. More than half of the world’s population now lives in urban centers, and this proportion is expected to increase to nearly 70 percent by 2050.3

While urbanization has helped improve living conditions for millions of people around the world, there are often chronic economic and social disparities among city dwellers. In the developing world, one out of three urban residents still lives in slums with inadequate basic services.4 Meanwhile, across all the countries that are part of the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), the income gap between the richest and poorest 10 percent of the population has increased by almost 30 percent over the last 25 years. In both settings, historically marginalized communities, including low-income, elderly, immigrant, and disabled residents, have not always shared in the prosperity of urban revitalization.5

These widening inequalities have brought the concept of inclusion to the forefront of urban development: providing all residents with equal access to city services, and allowing them to participate in municipal decision-making and benefit from the city’s economic growth.6 These efforts have been reinforced by calls to action from the international community. In 2012, the United Nations established Sustainable Development Goals to guide its development agenda through 2030, including aiming to “make cities and human settlements inclusive, safe, resilient, and sustainable.”7

The case for inclusive cities

Cities that effectively foster inclusion not only offer greater opportunities for their residents but often also reap widespread economic benefits.

A study by the Urban Institute analyzed the relationship between inclusion and economic health in 274 of the largest cities in the United States over the past four decades. The study found that, with few exceptions, cities that are more inclusive have better economic health indicators than those that are not.8

Figure 1 shows a mapping of each city’s economic health ranking against its inclusion ranking. This inclusion ranking combines economic inclusion and racial inclusion, or the ability of residents with lower incomes and residents of color to contribute to and benefit from the economy. Economic inclusion measures income segregation, housing affordability, and the share of working poor residents. Meanwhile, racial inclusion considers racial gaps in homeownership, poverty, and educational attainment.

Being smart and inclusive

Over the last decade, smart city initiatives have leveraged technology in many different ways. Data platforms and cloud-based systems enable cities to gather comprehensive data and make data-driven decisions, mobile applications allow residents to more easily communicate with local government, and sensor technology and predictive analytics help cities better align services with resident needs and proactively respond to crises before they arise.9

For example, in Kolkata, India, a startup has provided postal addresses to more than 120,000 slum residents using geocoding technology, helping them obtain documentation to access government services, open bank accounts, and register to vote.10 In London, a joint venture between Google and the Royal London Society for Blind People is helping the visually impaired navigate the city’s transportation network using beacons to provide audio instructions via a smartphone application.11

However, there are also examples of well-intentioned smart city initiatives inadvertently deepening existing inequalities when they lack transparency, fail to engage community members, or overlook residents’ diverse needs and preferences. In particular, some early initiatives drew criticism due to a perception that they focused too much on high-income city areas and failed to distribute benefits equitably within the city.12 These challenges generally stem from a set of common missteps during the three overarching phases of a smart city initiative: design, implementation, and reflection (figure 2).

“Cities often think about [smart city] programs in a homogenous way, not an equitable way. Without understanding the people that are going to live in this smart city—what their priorities and problems are—we’re not going to get to them … So, we must be very intentional about how we deploy for those communities.”—Aura Vasquez, former commissioner, Los Angeles Department of Water and Power13

Applying an inclusion lens to digital service delivery

Recent smart city initiatives have sought to address these issues by focusing on the needs and preferences of city residents rather than the capabilities of connected infrastructure. The latest generation of smart cities uses data, digital technology, and human-centered design to promote decision-making, not only by government but also by residents, businesses, and other city stakeholders. Taking this democratization of urban development a step further, some cities are inviting residents to cocreate solutions to local problems by empowering them with the requisite resources, skills, and knowledge.14

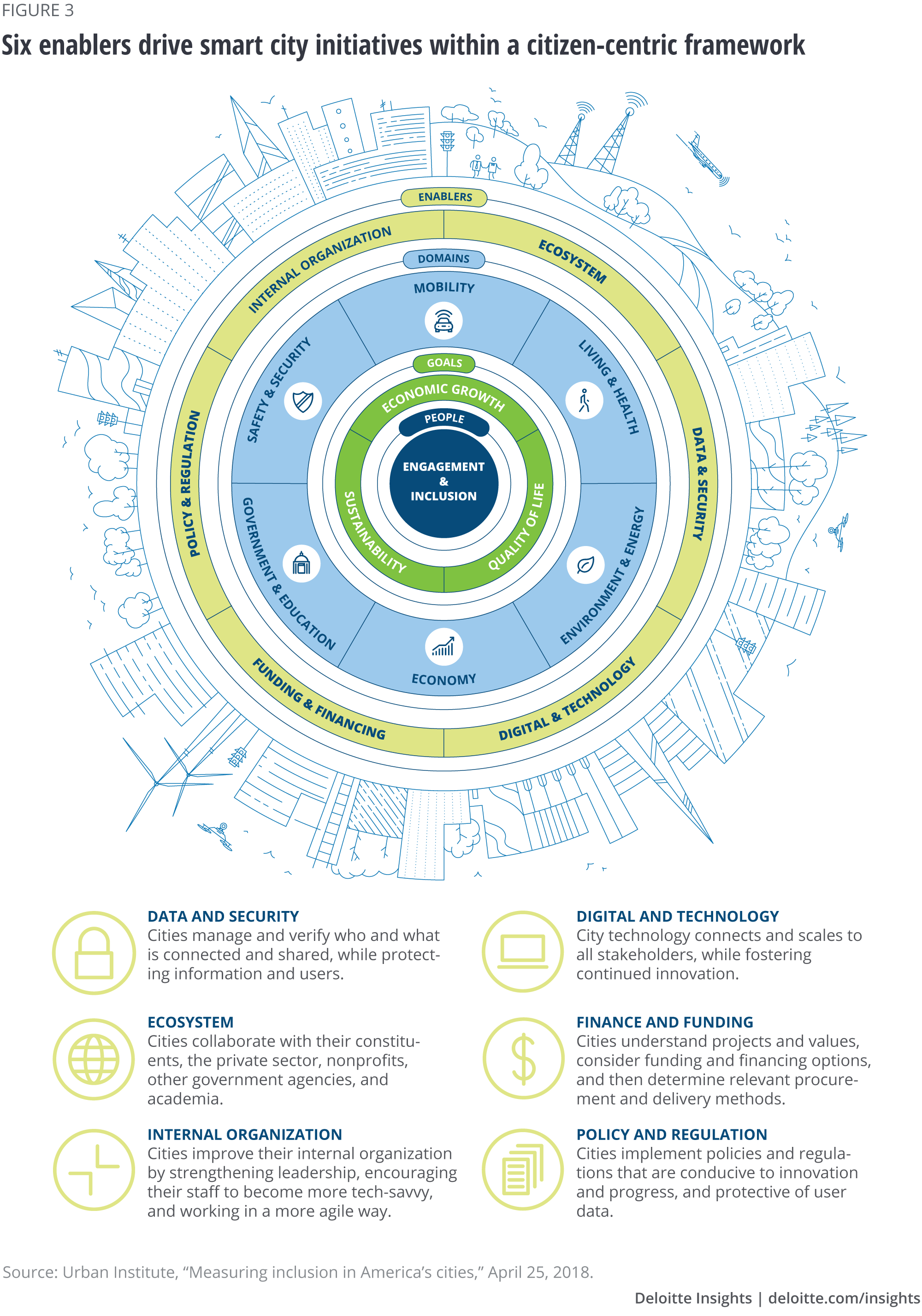

Smart city initiatives that shift from being technology-centric to citizen-centric put engagement and inclusion at the center, as shown in figure 3. Using this framework, cities have more tools to engage diverse stakeholders in solution creation and share the benefits of smart cities—quality of life, economic growth, and sustainability—with all residents. Six enablers work around these core principles to bring smart cities to life: data and security, digital and technology, ecosystem, finance and funding, internal organization, and policy and regulation.

Data and security: Increasing representation and transparency in government data

The emergence of digital platforms and connected devices has propelled cities to integrate data throughout their government processes, driven in large part by a desire to enhance efficiency and tailor services to residents’ needs. Yet when governments collect incomplete data or fail to engage residents in decisions regarding how their data is used, they run the risk of undermining the utility of and trust in public data management.15 They can avoid these pitfalls through the following approaches.

Protect the digital rights of residents

When city leaders engage directly with residents to build and codify digital rights—the rules by which cities collect, use, and protect data on city residents—they promote social trust and buy-in for smart city initiatives that rely on public data. Digital rights can materialize in privacy and use policies, technological sovereignty directives, and free software tools that allow residents to interact with public data more efficiently.16 Amsterdam created the “Tada-data disclosed” manifesto that is signed by over 80 government and private sector organizations. This document lays out the six principles of data use in Amsterdam: inclusive, controlled by the people, tailored to the people, legitimate and monitored, open and transparent, and from everyone and for everyone.17

Address “digitally invisible” populations

Some city leaders have difficulty collecting the data of hard-to-reach, “digitally invisible” residents. Chief data officers and policymakers can address this issue by improving the management of public datasets,18 which typically involves maintaining an inventory of data across organizational silos, mapping the data journey from the point of collection, and identifying digitally invisible populations. Cities can also enlist the support of local community leaders, conduct in-person outreach, and use multilingual formats to overcome common trust, resource, and language barriers to data collection.19 The city of Syracuse’s open data platform, DataCuse, aims to consolidate data from across city departments into a single platform accessible to residents, civic organizations, businesses, and other interested parties. The city also has 24/7 access to interpreters to improve communication with residents with limited English proficiency.

“Ultimately, city data is the property of the people, so we have a duty to be good stewards of their information. It’s a modern-day imperative for government: to be transparent about what we are doing and responsible in managing and using the people’s data.”—Ben Walsh, mayor, city of Syracuse20

Eliminate data-driven biases

In addition to evaluating data privacy and transparency, cities can gauge the accuracy and impact of data-driven algorithms that guide policies and operational decisions. Advocates for historically marginalized groups argue that these analytical tools sometimes unconsciously discriminate against residents based on demographic information, such as bail bond algorithms that assign higher risk scores to black defendants and child neglect predictors that disproportionately target poor families.21 Cities can address these concerns by proactively evaluating algorithms for biases and being more transparent about how the resulting analyses are used to inform positive interventions. Johnson County in Kentucky developed an algorithm that predicted when previously incarcerated residents with a history of mental health issues were at risk of recidivism. Rather than using this data to monitor and police these residents, the county focused on connecting them with mental health resources.22

Digital and technology: Expanding digital access and skills

Residents’ participation in smart cities is contingent on their ability to access and navigate digital channels and services effectively. Despite expansions in urban broadband infrastructure over the last two decades, many city dwellers still lack high-quality internet access.23 Advancements in cellular network technology and the advent of 5G internet have the potential to dramatically expand wireless internet capabilities and improve connectivity for mobile-dependent populations.24 While these trends represent a step in the right direction, many cities still face internet adoption and usage gaps along geographic and economic lines.25

Assess internet infrastructure availability

Cities looking to expand digital connectivity can begin by assessing the availability of internet infrastructure and cataloging the various modalities by which services are accessible. Using this information alongside internet adoption data, cities can identify households that may be excluded from digitally enabled services. In Kansas City, Google Fiber conducted a comprehensive study of internet access on behalf of the municipal government to help guide the expansion of internet services to low-income communities and inform the city’s digital equity strategy. The study included an analysis of the types of services that connected residents without broadband (i.e., using slower internet speeds) could not access.26

Conduct surveys of internet adoption rates

Even in cities with widespread internet coverage, gaps in residents’ connectivity may still exist. Internet adoption rates can vary based on the affordability of internet plans and residents’ willingness to pay for them. Neighborhood internet adoption surveys help cities better understand why some residents choose not to subscribe to these services and accordingly establish tailored programs to improve adoption levels. The city of Seattle issues a technology access and adoption survey every four years under its Digital Equity Initiative; the survey includes both demographic details and specific broadband performance measures.27

Establish digital literacy programs

Beyond internet access and adoption, cities should also ensure that residents have adequate digital knowledge and skills. Many nondigital natives do not know how to use an internet connection to find information, access services, look for jobs, or complete homework. Working with libraries, educators, community centers, nonprofits, and businesses, cities can establish digital literacy programs that teach residents basic skills for operating a computer, navigating the Web, and keeping their data secure.28 The city of Louisville partnered with various private partners and municipal agencies to help improve its residents’ digital literacy. One such partner was Google Fiber, whose “Grow with Google” program included digital skills training for community partners and one-on-one mentoring for residents.

“We need to think beyond whether families have broadband connections to how they use those connections to succeed in the community. We think of it as a three-legged stool: The internet enables it. The hardware leverages it. And the skills piece brings it all together.”—Grace Simrall, chief of civic innovation and technology, city of Louisville29

Ecosystem: Driving community cocreation

Many cities are embracing new community engagement models that bring residents, civic organizations, businesses, and other city stakeholders into the solution creation process. This cocreation approach can produce solutions that are more closely tied to the needs of city residents and promote broader stakeholder buy-in for new initiatives.30 However, when historically marginalized groups are excluded or underrepresented in this type of collaboration, cities risk designing solutions that may not meet their needs.

Establish inclusive living labs

Living laboratories are dedicated public spaces where cities can test smart solutions in a real-life context and understand how they interact with residents and public infrastructure. They allow cities to assess how an initiative may be received by various constituents and make any necessary adjustments prior to rolling it out to the whole city.31 As the city of Boston began to scale up its smart city efforts, the Mayor’s Office of New Urban Mechanics formed Boston Beta Blocks—dedicated areas with diverse constituencies that test and evaluate new technologies. Each zone has a dedicated zone advisory group, made up of representatives from neighborhood associations, health collaboratives, small businesses, and local youth groups, that provides feedback directly to the city government.

“We want to be sure that we are being completely open to communities to give us whatever type of feedback they want to. Some of that might be ‘don’t put that in my neighborhood,’ and that is a response that we value.”—Jacob Wessel, public realm director, city of Boston32

Develop resident advisory committees

A smart city advisory committee comprising city residents serves as a platform for committee representatives to voice their community’s needs and preferences. In some cases, cities may formally integrate resident advisory committees into broader smart city planning and governance processes. In Toronto, the Planning Review Committee selects residents through a civic lottery to represent the broader resident population in city planning efforts, which includes some smart city initiatives. Committee representatives proportionally match the city’s gender, age, and minority demographics based on the latest census.33

Use multimodal crowdsourcing

Multimodal crowdsourcing involves gathering pain points, ideas, and feedback from community members via different modes of information exchange. Cities can use a variety of digital tools to tap into the collective intelligence of constituents—but they should also conduct offline outreach to account for diverse communication preferences. Jerusalem’s innovation team issued a survey to the community to brainstorm ways to grow local small businesses. Recognizing the diverse cultures within the city, the survey was distributed in Arabic, English, and Hebrew. Facebook was used to reach the Arab and secular Jewish neighborhoods, while in-person canvassing was used to reach the ultra-Orthodox communities. The survey received more than 100,000 responses from 15,000 people.34

Finance and funding: Incentivizing inclusive innovation

Funding smart city initiatives, which are typically characterized by large upfront technology costs, is often a persistent challenge for city governments and can be even more difficult for projects targeting low-income or hard-to-reach populations. Without dedicated financing mechanisms and funding sources for inclusive initiatives, cities can struggle to incentivize solution developers, technology providers, and other private sector actors to deploy solutions that benefit historically marginalized groups.

Develop private-public inclusion funds

Local governments can pool public and private sector funds to address specific equity challenges by aligning public and private sector incentives around technology usage and economic growth. In particular, cities can work with telecommunications and technology companies to invest in expanding internet access and digital skills, which benefits local communities while also broadening these companies’ customer bases. Federal policies and grants may help raise capital, such as Opportunity Zone designations that provide preferential tax treatment for investments in economically distressed communities.35 The US$24 million San Jose Digital Inclusion Fund, which aims to close the digital divide, is supported by revenue from small cell usage fees paid by telecommunication companies to upgrade broadband networks, in addition to other public and private funding.36

Develop and launch innovation challenges

City-sponsored innovation challenges can be an effective method for spurring public innovation and unlocking private sector investment using a limited amount of government funding. Innovation challenges typically involve a government commitment to provide seed capital to solution developers focused on addressing specific urban challenges identified by city leaders. These programs can help demonstrate the viability of new technologies and service models while also evaluating the impact they have on the community. The US$8 million Michigan Mobility Challenge was established to generate mobility solutions for the elderly, disabled, and veteran populations—groups often left out of the rapidly changing smart mobility landscape. The challenge received over 40 proposals and awarded 13 grants.37

Leverage competitive procurements

Cities can leverage their purchasing power to incentivize service providers to address inclusion challenges. When issuing procurements, cities can require bidders to include considerations in their proposals, such as how they will engage underserved communities, track inclusivity, and mitigate exclusionary practices. In its Regional Smart Mobility Assessment request for proposals, the city of Nashville requested outreach support to engage various stakeholders, including “representatives of traditionally underserved populations.”38 Many cities are using competitive procurement strategies to reduce broadband access gaps by mandating that providers offer affordable plans for low-income households.39

Internal organization: Driving intergovernmental collaboration and tech-savvy staff

Smart city initiatives span a wide range of domains and applications, but are often planned and executed by centralized chief data, technology, or innovation officers. While these offices house the resources needed to manage technology investments, they rarely possess the long-standing community relationships held by other city departments, such as health, economic development, or family agencies. Cities have adopted new internal processes, workforce capabilities, and governance models in an effort to overcome this organizational challenge.

Create internal councils with ties to underrepresented communities

A dedicated inclusion council staffed with representatives from city agencies who have ties to underrepresented populations can help smart city initiatives reflect the true diversity of their residents’ needs. Cities can empower these councils by mandating their approval of new smart city initiatives and publicly elevating their profile. The government of the District of Columbia (D.C.) launched the Innovation and Technology Inclusion Council, an advisory committee that works with the mayor to improve economic opportunities for city residents and businesses. The council comprises 25 members, including representatives from government agencies focused on economic development, education, and technology; the innovation offices of local universities; and D.C. residents. The council collaborated with the mayor’s office to provide recommendations for closing innovation and technology inclusion gaps, such as access to broadband infrastructure; science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) educational programs; and entrepreneurial resources.

“Diversity is a defining characteristic of D.C.’s thriving innovation and technology ecosystem. We wanted to be intentional about working with our communities and sister agencies to grow our innovation and technology ecosystem in an inclusive manner. The Innovation and Technology Inclusion Council is helping us do just that.”—Joy James, technology and innovation portfolio manager, government of the District of Columbia40

Empower city employees with technology skills and tools

As technology is increasingly embedded throughout cities’ operations, innovation offices can arm other city departments with the tools and skills needed to develop smart solutions that address inclusion challenges. For example, San Francisco’s chief data officer created an in-house data academy that hosted workshops to help city employees use data more effectively. The workshops train staff on relevant data tools and skills and serve as informal channels for cross-departmental knowledge sharing.41

Embrace cross-departmental communication

Cities can also formalize processes and systems that break down knowledge silos that limit the reach and efficacy of smart city initiatives, such as cross-departmental communication channels, data-sharing practices, and data warehouses. In Los Angeles, all departments engaged in smart city pilots meet bimonthly to discuss status updates, opportunities for collaboration, available grants, data-sharing, and emerging technologies. This has resulted in greater coordination, such as the Bureau of Street Lighting’s sharing data collected by smart street lighting applications, related to environment, health, and other areas, with relevant departments.42

Policy and regulation: Making inclusion a strategic imperative

Cities use policies and regulations to set expectations and guidelines for smart city initiatives. When enacted properly, these tools can serve as effective platforms for managing private vendor influence and protecting the interests of underrepresented populations. Yet in many cities, innovation is outpacing policy development and leaving behind existing frameworks that are too broad to govern emerging technologies. Many residents and advocacy groups are encouraging cities to update these outdated frameworks to address growing data privacy concerns and improve accountability for stated inclusion goals.43

Develop privacy policies that put citizens first

Many cities have broad privacy policies that aim to protect the rights of their citizens; at the same time, new technologies and data collection practices, such as cameras and video surveillance, have amplified privacy concerns of many residents.44 To manage these concerns, cities can better educate the community about the objectives and capabilities of proposed technologies, engage community members in an ongoing dialogue about privacy issues, and solicit resident input on how and where certain technologies can be used. In 2013, Oakland residents protested the expansion of the municipal Domain Awareness Center, a hub that aggregates the data and operation of surveillance technology within the city. In response, the city worked across departments to develop a privacy and use policy for the center and establish a permanent resident-led Privacy Advisory Commission (PAC). The PAC recently passed the city’s Surveillance Technology Ordinance, which mandates that any technology employed by the municipal government undergo an impact assessment and be accompanied by a policy that clearly states how it can and cannot be used.

“It’s about process. It’s important for any Oaklander to know that for any technology, we looked at the impact on civil liberties and equity and developed a use policy based on that.”—Joe DeVries, chief privacy officer, city of Oakland45

Update municipal regulations to reach hard-to-serve residents

Municipal policies and regulations, such as permitting, licensing, and zoning rules, are levers that city governments can pull to advance more inclusive technology deployments. Cities can require technology vendors to deploy solutions in a more inclusive manner and lower regulatory barriers for providers that address inclusion challenges. The Department of Transportation in Washington, D.C., enacted a new rule that requires dockless vehicle operators to offer nonsmartphone options for trip rentals, low-income pricing plans, and more equitable daily distribution of the vehicles in all eight municipal wards. The city also incentivized the disbursement of adaptive vehicles for people with disabilities by exempting them from the vehicle quota.46

Establish inclusion-oriented goals and metrics

Municipal governments can demonstrate their accountability and commitment to digital inclusion by including goals and metrics that measure the inclusivity of smart city initiatives in citywide strategic plans. In 2013, the city of Chicago published a technology plan that contains performance indicators for digital access, digital engagement, quality of services, and digital workforce growth to evaluate the success of technology-enabled initiatives.47 The city government is now partnering with G3ict and World Enabled, nonprofits focused on inclusive and accessible technology design, to pilot a new assessment tool to track progress and guide the city’s future technology planning efforts.48

Where do cities start?

As city governments contend with the needs of growing populations and increasing pressure for equitable digital service delivery, they have a lot to consider. While many are already beginning this process, some cities are still figuring out where to start.

Here is a set of simple questions oriented around the design-implementation-reflection framework discussed earlier. No matter where a city is in its smart city journey, city leaders can use these questions to apply an inclusion lens to the development and evaluation of smart city initiatives. The answers will likely reveal gaps and opportunities to plan, implement, or improve smart city initiatives.

Design

- Have we engaged a diverse group of city residents to understand the needs and challenges they face and integrated these findings into the solution design?

- Have we considered whether our technology or program design will miss key segments of the city’s population?

- Have we engaged with other city agencies and partners who have deep relationships with historically underrepresented communities in our city?

- Have we employed innovative finance and funding strategies that support improved service delivery for low-income or hard-to-reach city residents?

Implement

- Do city residents agree on a common vision for the initiative, and is there an engagement mechanism in place to gather and incorporate their feedback throughout implementation?

- Have we chosen pilot locations that enable us to test the performance of the initiative with a diverse set of residents?

- Have we brought city residents into the conversation about data privacy, and have we put in place policies and procedures to safeguard the data we collect?

Reflect

- Have we selected performance metrics and collected data that will fairly represent the initiative’s performance across a diverse set of demographics and geographies?

- Have we directly engaged the community to understand how residents feel about the initiative?

Smart, connected infrastructure and data-driven technology have the potential to improve the lives of millions of urban residents in the United States and billions around the world. Yet many urban dwellers fear smart city efforts will serve only the affluent and fail to safeguard their data and privacy, potentially increasing divisiveness and inequality. Cities that make inclusion and engagement a cornerstone of their smart city efforts can build long-term trust with their communities and ultimately realize the full potential of these initiatives.

© 2021. See Terms of Use for more information.

Learn more about smart cities

-

Smart cities Collection

-

Addressing homelessness with data analytics Article5 years ago

-

Smart government Article5 years ago

-

Renewables (em)power smart cities Article6 years ago

-

Making smart cities cybersecure Article6 years ago

-

Making micromobility work for citizens, cities, and service providers Article6 years ago