Strategies to overcome scale-related challenges

Establish and/or strengthen the results management office (RMO): When overseeing a portfolio of projects, it is critical to have a project management office (PMO) that tracks progress in terms of spending and project milestones. A central office that tracks progress, funding applications, and expenditures for a group of initiatives can provide decision-makers a 360-degree view of funding flows.

Taking the idea further, public officials could establish a results management office (RMO), which not only plans and tracks progress on a portfolio of projects, but also provides a focus on mission-related results—the outcomes of these projects. Leaders can use an RMO to drive progress by coordinating across agencies, facilitating decision-making, and helping overcome barriers to progress. RMOs can also develop common reporting systems to help agencies measure results on an ongoing basis.6

Depending on the portfolio of projects involved, a PMO or RMO might be at the state or local level or at the level of either a state, local, or federal agency. Agency-level tracking can be easier to administer but could reinforce existing silos.

For example, to monitor the effectiveness of installing electric vehicle (EV) charging stations with IIJA funding, a state-level RMO might track multiple goals such as an increase in EV adoption, coverage of stations across different areas in a region, and compliance with federal spending requirements. It could also track critical outcomes such as job creation, workforce development, and equity. The RMO then becomes a critical resource for documenting not only how federal dollars were spent, but the impact of that spending.

Maintain a holistic view of initiatives: To avoid tackling just one small piece of a puzzle, agencies should understand the larger system. Identifying linkages between the laws provides a more holistic view. Take EVs, for instance. IIJA provides $5 billion for EV charging infrastructure. The IRA catalyzes adoption of that network through tax credits of up to $7,500 for new and up to $4,000 for used clean vehicles.7 These investments are designed to work in harmony to further a vision of more sustainable transportation. If the chargers aren’t built where EV demand is high, or if consumers lack access to chargers when tax credits materialize, the investments may fail to create the intended impact. The impact to the power grid is a key consideration as well.

Similarly, an RMO can provide a holistic view of projects, including furthering a “dig once” approach for projects spanning across transportation, broadband, and water. Given the high costs and disruption of digging up roads, some small delays to coordinate would be well worth it. Officials can start by identifying the interactions between interrelated initiatives.

Expand the talent pool: Successful implementation of these laws will require access to skilled professionals. State and local governments will need to develop, borrow, or buy this talent. Public leaders should explore investing in their own workforce, working with external partners such as universities to help develop their staff, and supplementing the public workforce through contractors and secondments.

An important objective of the legislation—which offers unprecedented levels of funding to help boost skills—is to augment the private sector talent supply through workforce development initiatives. Governments should identify the skills shortfalls that the industry may experience in the implementation of these programs, and invest in innovative partnerships with government, industry, nonprofits, and educational institutions to close those gaps. Given the surge of investment in transportation, broadband, and green energy, certain construction skills are likely to become execution bottlenecks.

Getting more young people interested in the trades early on and building awareness about apprenticeships and careers in construction, civil engineering, or transportation will be key to creating a steady pipeline of workers. States such as Indiana, Arizona, Texas, and Washington have been emphasizing the benefits of construction jobs, including their potential to pay entry-level professionals more than a liberal arts degree might.8 With the motto “Graduate Saturday, jobsite Monday,” Indiana’s Civil Construction Pathways Program offers high school students a three-year career pathway into construction.9 The curriculum includes lab activities on paving, bridges, construction inspection, erosion control, heavy-equipment operation, etc., followed by an internship with a local company in their senior year.10

Complexity: Many participants collaborating on multiple goals

Some tasks involving large expenditures can be relatively straightforward to execute, such as increasing the benefit level of an existing program. Other tasks, however, come with more complex execution challenges, and that’s the case with the many programs stemming from the IIJA, IRA, and CHIPS.

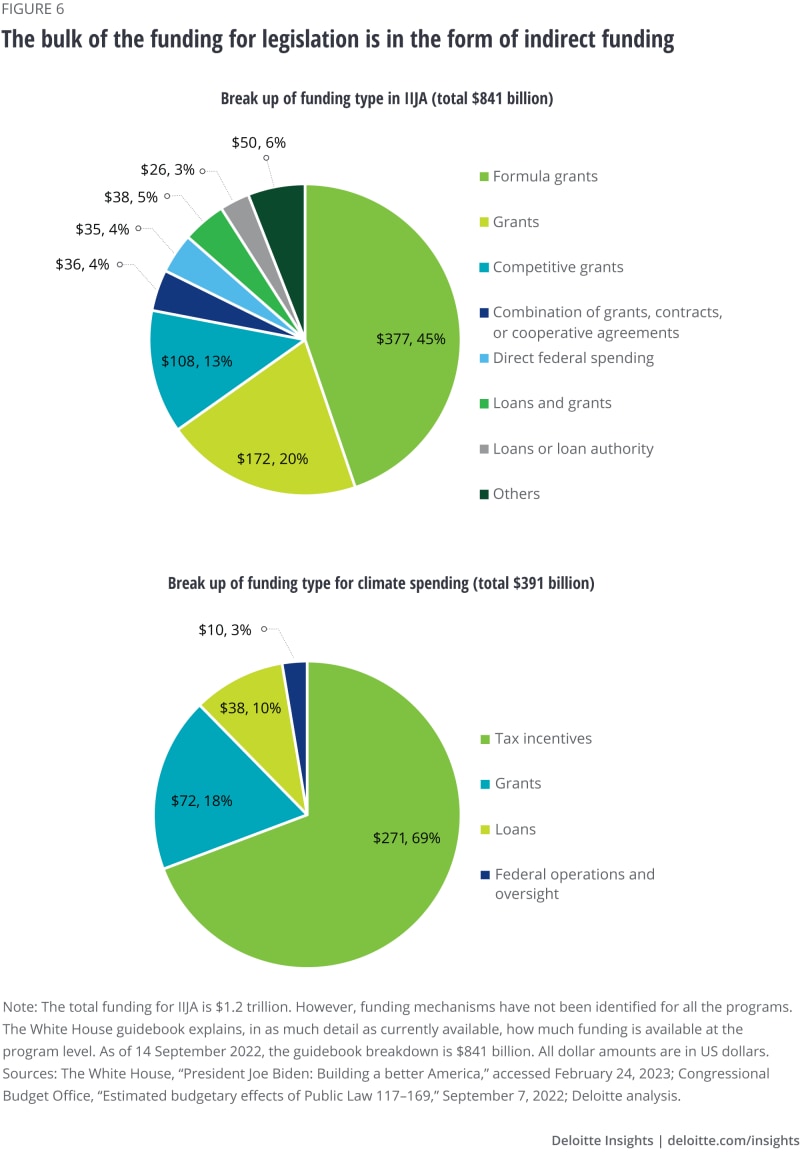

These laws create myriad new programs. They have numerous initiatives with detailed legislative language that may require clarification and input from several agencies. They establish competitive grants, tax credits, and other indirect payments, with funds flowing not only to state and local governments, but to businesses, nonprofits, and academia.

Under IIJA alone, more than 45 federal bureaus and 16 federal agencies and commissions are allocated funding for 369 new and existing programs.11 Grants fund more than 200 programs and represent 78% of the total funding.12 The multiple programs, levels of government, and goals bring with them complexity challenges.