Delivering innovative, better, and lower-cost state government The State Policy Road Map: Solutions for the Journey Ahead

07 February 2018

Such technologies as digital government, online self-service, and artificial intelligence offer government leaders a chance to rethink workflows and reduce costs often while enhancing service levels.

What is the issue?

A decade after the Great Recession, a number of states still face budget challenges. In 2015, 22 states had expenditures exceeding total revenues;1 30 states faced revenue shortfalls in 2017 and 2018 or both, according to the Center for Budget and Policy Priorities.2 Like always, money is tight.

Most governors are looking for ways to reduce costs without cutting programs. While you may think most of the low-hanging fruit has already been picked, such strategies do exist.

Learn more

View the full collection

Subscribe to receive Public Sector content

View the table of contents and create a custom PDF, or download the full collection

Sign up for the webcast

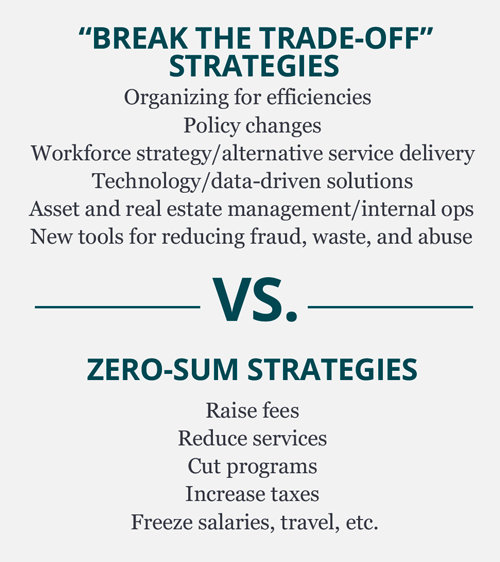

An ongoing challenge facing public operations is the trade-off between cost and quality. One way state leaders can address this challenge is to embrace new thinking and break the trade-offs through innovation. In the private sector, this takes the shape of making a better product for lower cost. For example, in the past, you could either serve lots of people with a standard product, or a small number of people with a customized product. Today, through personalization technologies, there is the potential to do both, and break the trade-off to offer “mass customization.”

In government, innovations that break the trade-offs can involve new technologies, new policies, or new service models to deliver equal or better quality for less money. Nesta, a UK-based think tank, calls such an approach “radical efficiency”: the art of developing different and better models—not just lower-cost versions of existing ones.3

Issue by the numbers: Breaking the cost-quality trade-off

- Thirty states face expenditures exceeding total revenues in FY17, FY18, or both (figure 3).4

- Some states have fallen further behind on funding their employee pension systems. The gap between state pension liabilities and assets grew to $1.1 trillion in 2015.5

- Huge savings may be possible from new automation technologies. The Deloitte Center for Government Insights projects that state governments can realize time savings of between 4 and 30 percent by implementing automation technology in the next 5–7 years. This translates to between $119 million and $931 million in potential annual savings.6

How can state leadership tackle the issue?

A new administration can be an opportunity for state leaders to look at state operations with a fresh set of eyes. Rapid changes in technology can create a chance to borrow great ideas from commercial best practices. Advances in understanding the customer experience likewise offer opportunities.

But what’s the best way to approach such an effort?

A methodical approach

Rather than starting with a set of preconceived notions and a few “prime targets” for cost reduction, taking a more methodical approach may be more effective. Start with analyzing your data—expenditure data, budget data, HR data, and performance data. The results of the analysis will identify some potential focus areas. With these focus areas identified, cast a wide net to generate ideas. Reach out to employees, senior government executives, think tanks, consultants, academics, and other partners.

The next step is key. How to choose from among the (hopefully) long list of cost-reduction ideas? One of the best approaches is to treat each idea as a “hypothesis” and critically test that idea against a set of criteria, including:

- Investment required

- Time horizon

- Likely return on investment

- Complexity and risk

- Impact on service levels

- Impact on state employees

This step can also include input from focus groups, surveys, and other “crowdsourcing” instruments. By critically testing these hypotheses up front, you can bring the best ideas forward.

Now, you can prioritize these ideas and start to execute with confidence. With a data-driven approach, you are more likely to pull the right levers and overcome possible resistance.

There may be opportunities for “incremental” cost savings—but saving even a small percentage of a large operation can generate meaningful savings. There may also be opportunities for more dramatic savings. For example, if you charge $20 for annual license renewals, a policy change could enable you to charge $60 for a three-year renewal instead—and cut the total number of transactions by 67 percent.

The break-the-trade-off ideas will likely fall into several different buckets.

Organizing for ongoing efficiency improvement

Develop institutional capabilities

Some states have created independent agencies that conduct periodic top-to-bottom reviews of state programs, agencies, and departments and make recommendations for maintaining, eliminating, redesigning, or restructuring them. Texas is one state with robust independent review capabilities. Created in the wake of a recession-led budget deficit, the Texas Performance Review (TPR), launched in 1991, resulted in savings of over $10 billion over the course of the next decade.7 Meanwhile, the Texas Sunset Commission has resulted in $981 million in savings and increased revenues over its 33-year history.8

Other states such as Arizona and Washington State are adopting lean thinking to maximize project impact while reducing waste.9 For instance, Arizona launched a results-driven management system called Arizona Management System based on lean principles. The idea was to track and improve state agencies’ performance on a regular basis, honing customer value. As a part of this initiative, the state has revised its processes and policies, saving millions. One such revised process is data-driven procurement, which helped Arizona achieve $20.4 million savings in 2016 alone.10 Similarly, following lean thinking, Washington State automated the monthly manual billing process, which involved 300+ organizations, generating savings estimated at $500,000.11

Build a balanced portfolio

To achieve results, leaders can build achievable, robust programs that contain a portfolio of initiatives to potentially reduce costs. Some pitfalls can include taking on too many initiatives at once and constructing a cost-reduction portfolio that lacks balance and coherence. This can lead to one initiative diluting the benefits of another and, possibly, a wider failure of confidence in the whole program.

Cost savings take a varying amount of time to extract. Think fast money and slow money. Fast money can come from opportunities that are not particularly complex to implement and where savings can be realized more quickly. Slower money can come from projects that are more complex, that may require a greater level of attention and management, or that have more dependencies with other projects underway. It can take years, for example, to extract savings from shared services, consolidation, and other changes in the government’s operating model. Additionally, the timeframe may be affected by the level of risk involved in the opportunity.

Workforce strategies

Personnel costs can represent a large chunk of state budgets. In looking for possible savings, state leaders may consider looking at functions that involve large numbers of public employees.

Outsourcing, automation, self-service, and other forms of alternative service delivery are several options state leaders can consider. Can the function be performed through self-service? Can parts or all of it be automated? Can it be contracted out or done through a public partnership? Can policy changes reduce effort with little or no impact on outcomes?

Careful workforce planning that takes advantage of natural attrition can help to minimize adverse impact on state employees.

Operating model: Reconfiguring bureaucratic structures to achieve policy outcomes in a different way

Often, the fiscal gap is so big that efficiency savings alone may not suffice. State officials can identify cost-reduction opportunities that change the shape and the way they do business, allowing services and policies to be delivered in a different way. This can take many forms, depending on the circumstances of the organization in question. Some common techniques that can help reduce costs through operating model change include:

- Implement shared services: Share back-office functions (for example, HR, finance, procurement) and delivery models with other departments or public bodies, including boards and commissions.

- Reduce overlap: Adjust the responsibilities of state agencies and departments by merging or modifying programs to reduce overlap.

- Rationalize: Reduce the number of agencies, units of local government, and “arm’s-length bodies” involved in delivering public services.

- Redesign: Adjust organizational hierarchies to increase spans of control and “delayer” middle-management roles through new workforce civil service paradigms and other means.

Changing the operating model can be harder than driving out efficiency savings because it can require state agencies and employees to fundamentally alter their ways of working and to adapt to a larger degree of change.

Policy choices: Changing costs without sacrificing mission

Policy choices can be a sensitive part of any cost-reduction program because they can affect large constituencies external to government. But this also represents an area where cost savings can be found without undue impact on core services. While some policy changes may require legislation, others may be accomplished through executive action.

Policy choices, in some cases, are rooted in long-ago decisions that established processes appropriate for the time but are no longer necessary due to technology changes. Does it really make sense to publish certain public notices in newspapers in the Internet age? Does having a different license plate for each county in the state justify the costs of managing multiple inventories? For that matter, is having a service office in each and every county the best use of scarce resources?

Reexamining existing policies can also reveal current practices that may be needlessly causing inconvenience to citizens. What is really gained by requiring documents to be notarized? Why can’t someone simply take a photo of his or her latest utility bill and email it in, rather than dealing with the hassle of finding an envelope and stamp to mail in a paper copy?

In some cases, there may be good reasons for continuing the current practices, but it never hurts to ask questions. Policy choices are driven by leadership, and cost-saving directives can often provide a useful spur to creative policy thinking.

Technology- and data-driven solutions

Rapid advances in technology, in areas including robotics, cognitive computing, and cloud, mean that almost every aspect of state operations can be reevaluated for streamlining through new technology.

In the past, tech upgrades in state government were often synonymous with large system implementations that were slow and costly to implement. Some systems will still fall under this category, but there are increasing places where more “lightweight” automation or cloud IT solutions can yield savings with less risk, less cost, and a faster payback in a shorter period of time.

The tech revolution is reshaping the economy, and state government is a target-rich environment for opportunities to use automation to improve efficiency. Mobile applications, for example, can allow field workers, such as social workers, to input and access critical data on-site, creating huge efficiencies without incurring massive costs.

Digital government, online self-service, artificial intelligence, and a host of other technologies offer a chance to rethink workflows, reduce costs, and in many cases to do so while enhancing service levels.

In addition, technology now allows for data-driven solutions that, through predictive analytics, can dramatically improve the allocation of state resources, from people to facilities to budget dollars.

Read more about how state governments can apply cognitive technologies in AI-augmented Government. |

Management by data to optimize programs and operations

Big advances in data analytics in recent years can help states save time, money, and energy.12 By making decisions based on data rather than intuition, states can allocate budget resources to maximum effect.

Consider Oregon, a leading state in using data to advance more evidence-based programs and services. The state targets many of its grants to local public safety agencies to test strategies that reduce recidivism and save prison costs. In human services, the state’s Pay for Prevention initiative directs funds to evidence-based interventions with the goal of preventing children and youth from entering the state’s child welfare and foster care systems in the first place, ultimately saving tax dollars.13

Asset management

From real estate and fleet maintenance to procurement and energy efficiency, state governments control significant assets. In some cases, practices established in the past may not be optimal today in light of new technologies or new practices. For example, states are now able to better understand usage patterns in offices and design flexible spaces that meet the needs of the modern and often mobile workforce. This can result in avoiding construction of new buildings or reducing the total square footage needed to support the existing workforce.

Internal operations

Robotic process automation (RPA) can replace the keystrokes on scores of repetitive manual tasks sometimes common in internal operations, allowing workers to focus on higher-value work. These technologies can take over repetitive tasks from human workers, freeing up those workers to perform more high-value activities. Bots, which mimic the actions of human workers, can automate processes in human resources, finance, payroll, IT, and procurement (figure 4).

Procurement rules and hiring processes are also potential targets for innovation. Finance and budgeting functions can be dispersed and highly manual.

Cutting fraud, waste, and abuse

Elimination of fraud, waste, and abuse is the equivalent of found money—money that can be spent on delivering real value.

Read more about fighting fraud, waste, and abuse in Shutting down fraud, waste, and abuse. |

Fraud perpetrators can be highly inventive. Keeping pace with them requires states to build anti-fraud systems that contain all relevant information and are capable of learning new fraud patterns on the fly. However, new tools that allow states to employ artificial intelligence-enabled fraud detection are coming online and can help states build such systems.

Tennessee’s Medicaid program TennCare took a holistic approach when it enforced statewide sharing of suspected fraudulent provider lists. The relatively simple policy, procedure, and technology changes associated with this move allowed Tennessee to save $50 million in one year, according to TennCare’s former director.14

Behavioral “nudges” can boost voluntary individual tax compliance

Tax systems overwhelmingly rely on voluntary compliance, for both individuals and corporations. Efforts to boost compliance through enforcement can be costly and difficult. The emerging field of behavioral economics, or nudge thinking, has the potential to increase revenues without raising taxes. A successful example of nudge thinking application comes from the Canadian province of Ontario, where the government turned to behavioral science to tackle delinquencies in employee health tax (EHT) filing by the businesses. To assist employers who were running late on filing, Ontario tested new messaging that focused on implementation intentions. In 2015, a subset of employers tweaked their collection letters, guiding participants about where they could file a return (directing them to websites and the mailing addresses of service centers) and providing detailed instructions for filing and deadlines. A month later, employers using the implementation intention approach reported a 13 percent increase in their filings vis-à-vis the control group that received the standard delinquent message.15

Nudge toolbox: Implementation intentions

Committing to a plan can help individuals accomplish a specific goal by spelling out “how, when, and where” they intend to carry out an action, which is known as an implementation intention. In a number of studies concerning fruit and vegetable consumption, people who expressed their dietary goals in an “if/then” format—for example, “If I am at home and I want to have dessert after dinner, then I will make myself a fruit salad”—consumed significantly more healthy foods.16

You don’t have to look far for inspiration

NCGEAR

In 2013, North Carolina launched an initiative to analyze and reform state government operations. Better known as the North Carolina Government Efficiency and Reform, or NCGEAR, this initiative was a “data-based approach to improving state government processes, enhancing customer service, and realizing cost savings and cost avoidance.”

After a comprehensive evaluation of the executive branch (which includes major state agencies), the NCGEAR published its final report in March 2015 with 22 reform recommendations. Following an eight-step process of opportunity identification, the initiative’s recommendations included a host of major changes, such as transitioning to an enterprise-wide approach for state programs and services from the current traditional agency-focused approach. The initiative is expected to result in savings worth $14 million in the first year, cumulating to $615 million by 2025 in net present value.17