Transportation trends 2020 What are the most transformational trends in mobility today?

27 minute read

13 April 2020

Transportation agencies are in the process of making mobility systems more seamless, sustainable, accessible, affordable, and safe. Here are five transformational trends helping shape the mobility agenda in 2020.

View sections

Introduction

If you want a glimpse into where mobility is headed in 2020 and beyond, look no further than the San Diego region. There, the San Diego Association of Governments (SANDAG) is laying the foundation for a complete overhaul of the region’s transportation system. The goal is to make the system more sustainable, accessible, affordable, and safe, while providing San Diegans’ true transportation alternatives to trips made in single-occupancy vehicles.

Learn more

Explore the Government & public services collection

Learn about Deloitte's services

Go straight to smart. Get the Deloitte Insights app

SANDAG is making this a reality through its “5 Big Moves,” which are transformative strategies to:

- Leverage technology, sensors, and connectivity to change the way roads are used and managed.

- Develop a high-capacity, high-speed, high-frequency transit network, that includes new modes of transit and improvements to existing services.

- Introduce new mobility hubs, with a range of travel options, to address first- and last-mile challenges and to deliver a more seamless travel experience.

- Introduce flexible fleets of on-demand, shared, electric—and eventually, autonomous—vehicles that connect to transit within a mobility hub.1

- Build an integrated platform called “Next OS” that will serve as “the brain of the entire transportation system.” Next OS—central to achieving systemwide optimization—will turn integrated data into insights that planners can use to better manage transportation systems and the movement of people and goods. In its fully-realized state, this platform will help to create a “mobility marketplace,” nudging behaviors and creating a better real-time balance between supply and demand (figure 1).2

Ultimately, SANDAG hopes to create a more integrated, user-centered, accessible, and affordable transportation system that, in time, will supersede the car-centric model that has reigned since the Model T took to the road in 1908.

San Diego’s sweeping plan is underpinned by five transformative trends we see shaping the mobility agenda in 2020 and beyond. They are:

- Integrated, frictionless travel: Transportation planners see a growing need to make travel more seamless, with minimal stoppages or checkpoints. This trend is manifesting in many ways, including mobility hubs that enable multimodal transportation, the rise of mobility-as-a-service (MaaS), platforms for ticketless travel, and innovations in micromobility and last-mile connections.

- Digital identity: Transit and transportation agencies across the country are using digital technology to increase throughput, improve security, and help drive a better experience for users. This trend includes a move toward digital driver’s licenses to enhance security, and experimentation with biometric and facial recognition to improve efficiency and throughput at airports.

- Customer experience: Transportation agencies and the broader mobility ecosystem are placing more emphasis on customer experience—putting the user’s needs front and center and making it easier to use digital transportation tools. They’re also simplifying in-person transactions at local departments of motor vehicles, providing better infrastructure for pedestrians, and offering more inclusive travel options in urban areas.

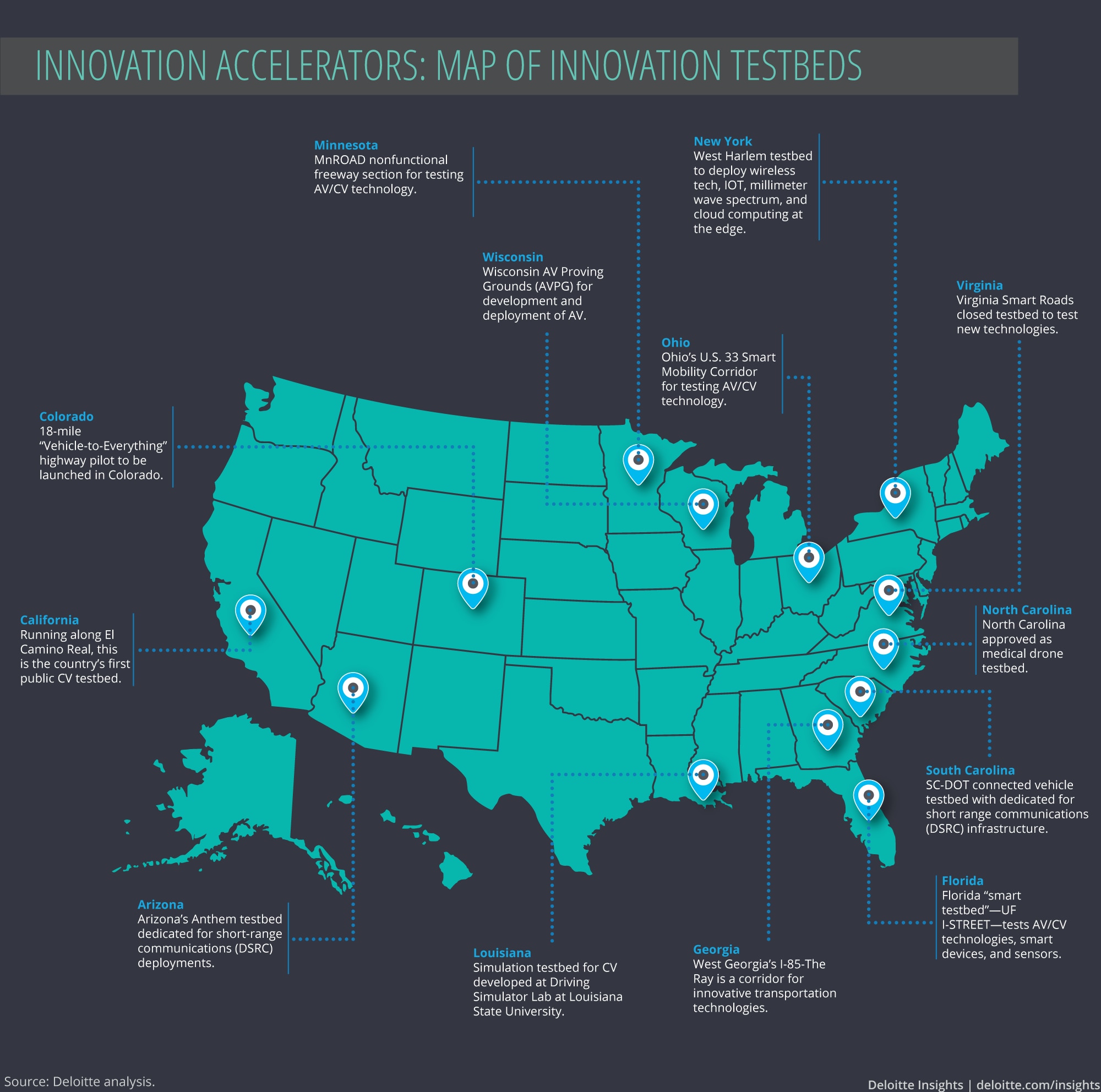

- Innovation accelerators: Transportation agencies are tapping into private sector expertise and building public-private coalitions to drive innovations in multimodal transportation, autonomous and connected vehicle technologies, mileage-based pricing programs, and much more.

- AI-augmented mobility: A transportation ecosystem enabled with artificial intelligence (AI) can harness the power of data, analytics, and cloud to help reduce travel time, manage congestion, improve regulatory compliance, support air traffic control, enable dynamic policymaking, and deliver many other benefits.

In this report, we examine these trends and how they are reshaping aspects of how people and goods move across the US transportation network—both on the ground and in the air. It is designed to assist public transportation leaders who see the necessity for change and are looking for innovative ideas to show the best way forward. Understanding these trends is a first step in navigating today’s fast-changing mobility landscape.

Sections

Integrated, frictionless travel

The principle of “moving people and goods from point A to point B” sounds simple. Dealing with the entire mobility ecosystem is anything but. Cities working to develop the mobility systems of the future face all sorts of complexities: varying geographies, different modes of transport and their interconnections, corresponding infrastructure requirements, varied payment methods, the difficulties of identity management, and much more.

But cities are moving ahead, experimenting with new infrastructure models and technologies to lay the foundation for more integrated and seamless mobility. Some of them, like San Diego, are going even further, entirely reimagining their mobility ecosystems.

Designing mobility hubs

A mobility hub locates multiple transportation services in one place, letting travelers move more seamlessly from one to another. Such a hub, while providing traditional transit services via bus, train, or light rail, might also: encourage walking; provide racks for bicycles on buses and trains; offer bikeshare, rideshare, and carshare programs; operate high frequency, local shuttle services; and enable other regional and local transit connections.4

With their integrated infrastructure, mobility hubs consolidate public and private modes of transportation to maximize first-mile and last-mile connectivity. They operate best when cities put them in areas with a high concentration of employment, housing, shopping, and recreation.5

Los Angeles’ Mobility Plan 2035 divides the mobility hub concept into three categories. Neighborhood mobility hubs, which focus on low-density population areas, include transit, wayfinding, bikesharing, and parking infrastructure. Central mobility hubs, designed for high-density areas, include carsharing, real-time transit information, public spaces, and electric vehicle charging stations. Regional mobility hubs are designed for very high-density areas, typically at the ends of transit lines. Besides the services available at central mobility hubs, they also offer layover zones for buses, substantial bicycle parking facilities, and retail space. The City of Los Angeles received a US$8.4 million federal grant to build 13 mobility hubs across the city.6

Mobility hubs are also an integral part of the San Diego Forward plan proposed by the 18 cities and county governments that comprise SANDAG.

The rise of mobility-as-a-service

Streaming services, such as Netflix, have fundamentally changed the way people search for, consume, and pay for media. Transportation now stands at a similar frontier.

Helsinki’s mobility-as-a-service (MaaS) app, Whim, was one of the first mobility platforms to envision an integrated, multimodal future. Since 2016, Helsinki residents have used Whim to plan and pay for all modes of public and private transportation within the city—be it by train, taxi, bus, carshare, or bikeshare.7 Other jurisdictions are following suit.

Take the Regional Transport District (RTD), which provides public transportation to eight counties in Colorado, including the city of Denver. RTD recently partnered with the developers of the Transit app to simplify multimodal trip planning. Users can now plan trips across public and private mobility providers, including transit systems, ride-hailing companies, and bikeshare services. The app also integrates a ticketing platform that lets users make payments to multiple transport providers at once.8 RTD’s focus is on adding multiple cross-platform options to its own app, making trip planning and payment more seamless.9

That said, many MaaS applications have struggled to gain penetration, and getting the full suite of transportation modes on a platform can be difficult. Questions also remain about how effective MaaS can be in drawing travelers away from private car use.10 Increasingly, the most successful models are those with close collaboration or sponsorship from the local transport authority, as in the case of RTD.

Ticketless public transit

In the United Kingdom, transit riders can use the Ticketless mobile-ticketing platform to move from one point to another with minimal friction.11 UrbanThings, the company behind Ticketless, will soon launch a pilot of the “Be-in/Be-Out” system, in which the traveler’s Ticketless app will communicate via Bluetooth to track their journey and manage fare collection without them having to take their phone out, providing a no-stop travel experience.12 Several cities in the United States are also moving toward mobile and integrated ticketing. The Las Vegas Monorail was the first public transit system to let passengers use Google Pay to purchase tickets. Customers of San Francisco’s 22 transit agencies will soon be able to pay for travel on their mobile devices. And Los Angeles plans to improve its TAP Smart Card to integrate payments across different mobility options.13

Making a case for micromobility

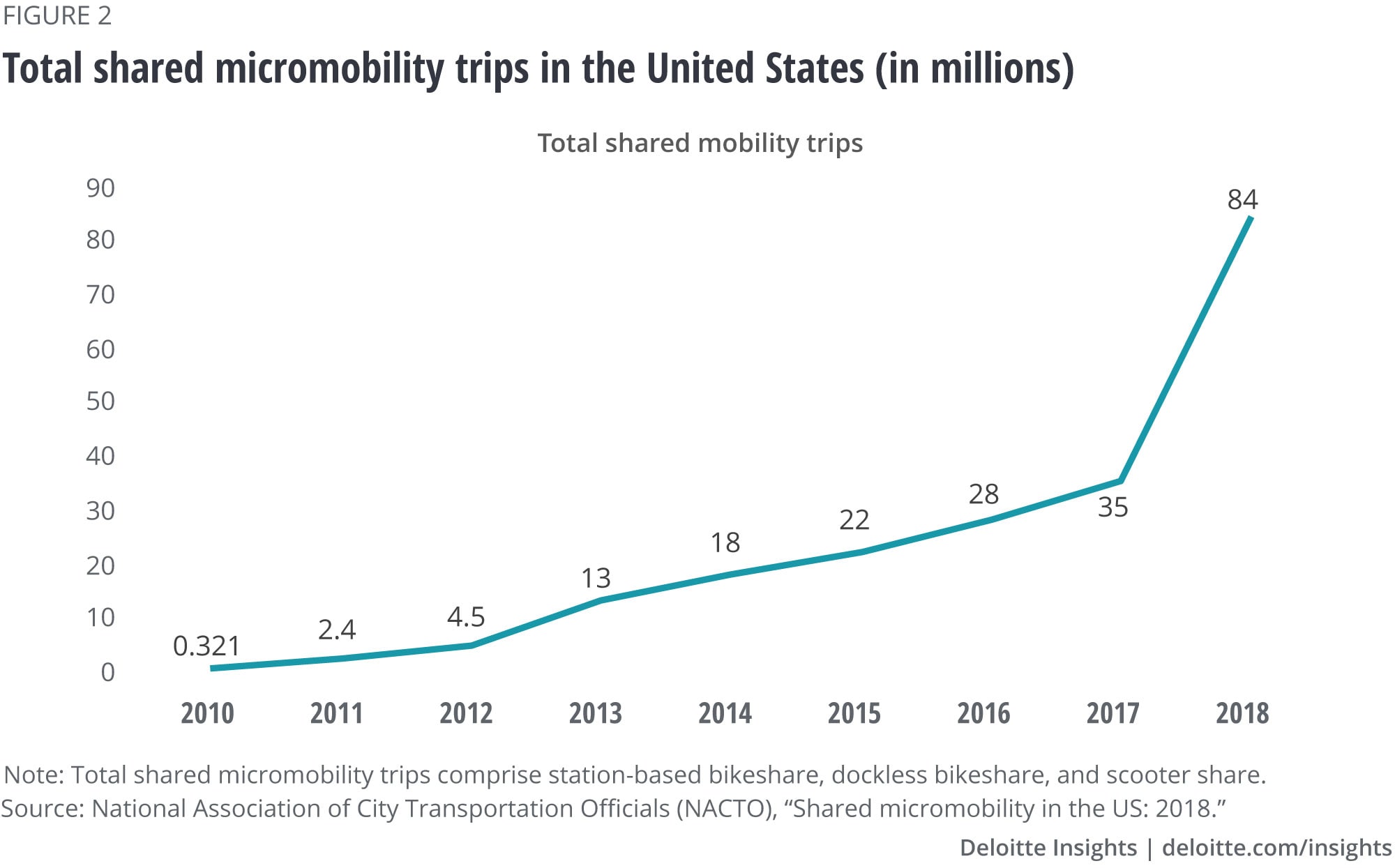

New forms of micromobility, such as electric scooters and shared bikes, promise to better connect people with public transit, reduce reliance on private cars, and make better use of travel space, all while reducing greenhouse gas emissions (especially as vehicle life spans improve). Micromobility is growing more popular (figure 2), but it also suffers from growing pains, and it often faces resistance, as seen in the sometimes rocky relationship between municipal governments and e-scooter companies. Although still in its infancy, micromobility could potentially help solve the first-mile/last-mile problem and narrow the gap between the transit services a community provides and the services its residents need. As with any other disruptive innovation, however, proponents of micromobility must find ways to balance the needs of cities, citizens, and service providers. To succeed, stakeholders will need to develop relationships built on trust, while still allowing competition and new entrants. [Read more: Small is beautiful—making micromobility work for citizens, cities, and providers.]

Digital identity

Transportation and border protection agencies and their stakeholders are using digital and AI-based technologies to give users a more convenient and secure travel experience. One example of the digital identity trend is the effort to digitize driver’s licenses. In the air, e-passports are already making inroads at airports globally, and efforts are underway to improve the traveler experience and security using biometrics and facial recognition technologies.

Moving from analog to digital driver’s licenses

Louisiana, Iowa, Colorado, Idaho, Maryland, and the District of Columbia are all in various stages of piloting and implementing digital driver’s license technology. A digital driver’s license is a digital copy of a driver's license that can be stored on a smartphone.14 In Louisiana, for example, drivers can store their digital driver’s license data on the VerifyYou app, which lets users authenticate the digital document with the state’s Department of Motor Vehicles.15

Not only do digital driver’s licenses increase convenience for citizens, but they could also reduce fraud as they’re less susceptible to counterfeiting or tampering than paper licenses. They also let law enforcement agencies quickly and securely view an individual’s data and verify their identity.

Frictionless airport experience using biometrics and facial recognition

The more people choose to fly, the more pressure they put on airport infrastructure, and the longer they must wait in queues at ticket counters and security checkpoints. In 2018, more than 1 billion passengers passed through airports in the United States.16 To help tackle this problem, many airports are deploying multiple technologies that can digitally identify travelers and speed up passenger processing.

With electronic and biometric passports (passports embedded with a chip containing biometric information) now available in more than 150 countries around the world, airlines and airports are turning to facial recognition and biometric systems to streamline the travel experience.17 At more than 40 airports across the United States, frequent flyers who belong to the CLEAR accelerated screening program can use their fingerprints to identify themselves when they board flights.18 Biometrics, in the future, could allow passengers to do away with multiple travel documents such as tickets, boarding passes, baggage tags, and other IDs.

A glimpse of this can be seen at Atlanta’s Hartsfield-Jackson international airport. Delta Air Lines, in collaboration with Customs and Border Protection (CBP) and the Transportation Security Administration (TSA), has launched the country’s first biometric terminal at the airport. The terminal uses facial recognition technology to move passengers quickly from the curb to the gate. Passengers opting to use the service can check in at the self-service kiosk and drop their checked baggage at the counter, never needing to scan a boarding pass or show a physical ID. They simply verify their identity through facial recognition at the TSA checkpoint and board their flights. More than 25,000 people used the service to expedite their movement through the airport within three months of it being rolled out.19

The final check-in with such a system happens at the boarding gate. Using CBP-powered facial comparison technology, the airline can match a passenger’s photo in real time with an image stored in a secure cloud database, thus allowing gate agents to skip scanning the passenger’s boarding pass. Over the years, CBP claims to have achieved an accuracy rate of 99 percent.20 However, challenges around security, privacy, and algorithmic bias remain and continue to be a major focus for federal agencies and industry partners.21

Customer experience

Department of Motor Vehicles (DMV) commissioners have long known that customers who are unhappy with services at their local DMV often take their complaints all the way to the governor’s desk. People transact a lot with local DMVs, which can make their experiences a bellwether for the constituent experience with the state and local government writ large. So, it’s no surprise that as an increasing number of jurisdictions across the United States appoint chief citizen experience officers to manage and improve the experience citizens have while interacting with government, transportation services rank high on their agendas.22

Transportation agencies themselves, along with the broader mobility ecosystem, are also placing more emphasis on customer experience (CX). That means putting users’ needs front and center, simplifying transactions, providing better wayfinding infrastructure for pedestrians, and offering more inclusive travel options.

Improving self-service at DMVs

In recent years, many DMVs have addressed the problem of long wait times for services and limited service hours and locations through a mix of technology and process changes. Many states have implemented self-service kiosks in DMV offices to handle routine transactions. They’ve also added kiosks at high-traffic partner locations, such as grocery stores, saving many citizens a trip to their local DMV branch. In California, for example, residents can visit a DMV kiosk to obtain vehicle registrations and license plate stickers, while also performing other routine transactions.23 Washington D.C. and Maryland residents can perform their own emissions screening using 24-hour self-service kiosks that feature touch screens and audio with step-by-step instructions on the inspection process.24

Building more inclusive mobility infrastructure

Federal data shows that nearly 20 percent of Americans—57 million individuals—have disabilities, and 6 million of those people have difficulty getting the transportation they need.25 To make it easier for pedestrians with limited mobility to plan accessible routes, the University of Washington’s Taskar Center for Accessible Technology has developed AccessMap, a map-based app that lets users enter a destination and receive suggested routes based on customized settings, such as limiting uphill or downhill inclines.26

Some cities are introducing new vendor requirements in an effort to deploy solutions that are more inclusive, in terms of both physical accessibility and cost. They’re also lowering regulatory barriers for providers that address inclusion. For example, new rules from the District of Columbia’s DOT say that operators of dockless vehicle services must offer rental options that don’t require smartphones. They must also offer pricing plans for users with low incomes and distribute their vehicles more equitably across the district’s eight wards.27

Helping pedestrians better navigate urban areas

Another important experience that transportation and infrastructure planners are trying to improve for travelers is finding their way around. Through its Legible London initiative, for instance, Transport for London (TfL) uses human-centered design principles to help citizens and visitors find their way more easily around the city. New tools include maps to indicate how far one can walk in five minutes or 15 minutes, taller signs to accommodate detailed information, transport interchange information, and traditional directional signs.28

Improving the transit experience

Customer experience plays a critical role in increasing public transit ridership. Increasingly, transit leaders are focused on building integrated digital platforms, offering diverse payment channels, and improving the use of data to better understand their customers in an effort to improve their transit experience.29 Offering integrated multimodal options digitally, like what RTD is doing in Colorado, is one way of providing a more seamless experience to passengers.

TransLink, the regional transportation authority in Vancouver, upgraded its fare system and now allows passengers to use wearables like wristbands for payment using their “pay-and-go” facility.30 Metrolinx, the regional transportation authority for the Greater Toronto and Hamilton Area, has partnered with a grocery chain to allow passengers to pick up their groceries from their home stations.31

Some cities are going a step further and creating positions in their transit agency focused on customer experience. In 2018, the city of Seattle appointed a chief customer experience officer (CCEO) for Sound Transit, the city’s transit agency serving the Seattle metropolitan area. The CCEO’s role is to ensure that CX is an integral part of all new transportation development in the city.32

Innovation accelerators

Transformative innovation requires an environment that celebrates risk-taking and urges people to learn from their failures. An organization that fosters innovation—including in the field of transportation—might focus on developing solutions of its own, or on driving innovation among other stakeholder groups.33

Tapping into private sector expertise and solutions

Some government innovation units in the transportation world focus on “spinning-in” promising solutions from other sectors, adapting them as needed. That’s what the US Department of Transportation (USDOT) did when it awarded US$14 million to Carnegie Mellon University to launch a transportation research center called Mobility21. One of the center’s critical goals is to follow up its research with pilots and then transfer successful technologies to partners in the “real world.”34 One of the solutions under development at the center is the Intelligent Mobility Meter (IMM), which counts the number of pedestrians, cyclists, and vehicles in a particular area. The project expands on previous counting solutions to develop better technical capabilities and counting accuracy, and has encouraged the use of these meters in real-world settings.35

Another example, from across the pond, is the partnership between TfL and Bosch to help tackle urban mobility issues in the United Kingdom. TfL brings technical knowledge and a plethora of data sets from its unified API and open data platforms. Bosch provides a dedicated space called the “Connectory” to serve as an urban mobility lab where researchers from across the mobility ecosystem can collaborate. Bosch also provides urban mobility experts to guide and mentor startups and small businesses in the transportation space.36

Setting up sandboxes to increase innovation

Transportation agencies can encourage innovation by creating sandboxes and related infrastructure for developing and testing cutting-edge technologies. Transportation agencies can derive value by enabling others to innovate more effectively.

Consider Suntrax, the state-of-the-art facility developed by the Florida Department of Transportation (FDOT) and Florida’s Turnpike Enterprise (FTE). The FTE currently uses the facility to test tolling technologies. By 2021, the facility will expand to support autonomous vehicle (AV) and connected vehicle (CV) testing on a 2.2-mile-long test track. Suntrax also provides a 200-acre facility to test AV technologies in highway, high-speed, and urban settings.37 Similarly, the Texas Innovation Alliance provides controlled testing facilities for AV technology in Austin, Houston, Dallas, Fort Worth, San Antonio, and El Paso.38 Michigan’s Mcity is another initiative that aims to build an AV and CV ecosystem. Launched in 2015, the program is led by the University of Michigan and 65 industry partners, with more than US$16 million in research funding.39

AVs hold the potential to make public roadways work markedly safer by addressing 94 percent of crashes caused by human error.40

Ohio is already home to the largest contained testing site for AV and CV technologies—the SMARTCenter. With a majority of AV and CV testbeds cropping up in urban areas, the USDOT recently awarded Ohio a US$7.5 million grant to pilot AV technology on rural roads. DriveOhio, a collaboration between Ohio’s Department of Transportation and academic partners, will lead this rural AV testing project.41

Officials at USDOT and Ohio DOT point out that 97 percent of land in the United States is rural and could be the ideal setting for testing and improving AV technologies. 42

Building a public-private coalition to drive transportation innovation

Along with states and the federal government, cities and local transportation agencies are also collaborating to create innovative transportation solutions. For example, Los Angeles recently launched the Urban Movement Labs (UML), a public-private coalition to drive innovation in transportation. The UML includes the Mayor’s Office of Economic Development, the City of Los Angeles Department of Transportation, Los Angeles World Airports, the Port of Los Angeles, and private partners including Lyft, Waymo, and Verizon. The coalition will also include partners drawn from the nonprofit world and academia, along with residents.43

The UML will generate solutions for the city’s daily challenges and then test those solutions on testbeds within the city. One of its initiatives, the Ideas Accelerator, will use a mix of crowdsourcing and cocreation models, allowing anyone to propose a solution or a problem that needs solving. The UML’s other initiatives focus on driving economic and workforce development in transportation and building testbeds to explore cutting-edge solutions in a controlled environment.44

In some cases, states, regions, and the private sector have come together to tackle particularly thorny mobility issues. For instance, the Mileage-Based User Fee (MBUF) Alliance was formed in 2010 to explore and pilot different MBUF models as alternatives to the gasoline-based tax funding model.45 The alliance unites multiple mobility stakeholders, including state transportation departments, businesses, think tanks, academic institutions, and transportation experts. The MBUF conducted its first road usage charge (RUC) pilot, OReGO, in the state of Oregon. Pilots have since followed in Delaware, California, Minnesota, Missouri, and Washington.46

Similar initiatives are trying to drive innovation in commercial freight transportation via road, rail, and air. AllianceTexas, a planned community within the Denton and Tarrant counties in Texas, serves as a global logistics hub for multiple freight companies, including the BNSF Railway, the Fort Worth Alliance Airport, FedEx’s Southwest regional sorting hub, and Amazon Air’s regional hub.47 AllianceTexas recently established a Mobility Innovation Zone to test and foster smart infrastructure and smart mobility innovation. For instance, the zone plans to test unmanned aerial systems (UAS) and autonomous integrated freight management systems in a sandbox environment.48

AI-augmented mobility

The growing toolkit of AI technologies—including computer vision, natural conversation, and machines that learn over time—has the potential to enhance almost every aspect of today’s mobility ecosystem. AI can enable intelligent transportation systems (ITS) in many areas, from traffic management and smart signaling to road safety improvements, transit scheduling, and real-time information for commuters.

According to studies, the global market for AI in transportation is expected to reach US$3.5 billion by 2023.49

Reducing travel time

The city of Pittsburgh has experimented with an AI-driven traffic light system that adapts to current conditions instead of following a preprogrammed pattern. Computer vision and radar enable the system to see vehicles coming from all directions. This traffic data powers a predictive model used to modify traffic signaling patterns in real time. The city initially installed this system at 50 intersections and plans to scale up to 150. The system has helped reduce travel time by 25 percent, braking by 30 percent, and idling by more than 40 percent.50

Active traffic management

Rather than using static time-of-day models, active traffic management (ATM) uses current and predicted traffic condition data to dynamically manage traffic and congestion on roads.51 In Seattle, the state of Washington has created smarter highway corridors that include ATM-based signage and variable speed limits to better manage incidents and maintenance of roads. On the Interstate 5 corridor where the system was implemented, the number of annual crashes fell from 434 to 296.52

Ensuring restricted lane compliance

With the number of high-occupancy toll (HOT)/high-occupancy vehicle (HOV) lanes on the rise, AI technologies can help inspect the number of travelers in a vehicle using a restricted lane. Currently, officers have to conduct manual inspections, making HOT/HOV lanes costly to operate and their restrictions difficult to enforce. Cities and states are exploring technologies such as vehicle occupancy detection systems that can help catch drivers who use restricted lanes illegally. Such systems use infrared cameras to capture images near toll lanes, with additional computer vision technologies to detect the number of passengers in the car.53

In 2018, California’s Metropolitan Transportation Commission allowed three companies to test their camera and video analytics technology in the state.54 The system uses video analytics technology to detect vacant seats in a vehicle, but it does not use facial recognition technology.55

Advanced air mobility

Along with AV and CV technologies, advanced air mobility (AAM) is gaining traction and has the potential to transform how we move goods and people in urban centers and regions. NASA and the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) are leading efforts to accelerate the development and safe integration of AAM into the US national transportation system. NASA is collaborating with a broad set of stakeholders to develop an industry concept of operations for urban air mobility (UAM). The goal is to describe a vision and the foundational concepts required to put air transportation within the reach of the public as a transportation option—shifting urban traffic into the airspace over metropolitan areas in the United States.56

The FAA has brought together state, local, and tribal governments, along with private sector entities, to test advanced unmanned aircraft systems (UAS) operations. Under this effort, UPS Flight Forward conducted its first package delivery by drone flying medical supplies at WakeMed's hospital campus in Raleigh, North Carolina on September 27, 2019.57 This was followed by approval for Google’s Wing Aviation, LLC to conduct package delivery operations.58 The AAM landscape is expanding with passenger and delivery drones’ potential to save time, reduce congestion, and improve logistics.59

Assisting air traffic control (ATC)

AI is also making inroads in aviation by assisting air traffic controllers. For instance, London Heathrow airport’s ATC has to deal with fog and low ground visibility from time to time. To tackle this problem, the airport has installed multiple ultra-high-definition cameras that send visual data to the AI system, Aimee.60 Analyzing the data in real time, Aimee tells controllers when an aircraft has exited and alerts them to clear the arrival of the next flight. Once fully operational, the system is expected to improve landing capacity by 20 percent.61 With an increase in urban air mobility, air traffic management systems will need to adopt a more scalable model. This is where unmanned aircraft system traffic management (UTM) comes into play. NASA’s Ames Research Center is currently leading the UTM project by partnering with more than 100 organizations across government, academia, and industry.62

The rise of “digital twin” capabilities

In a hyperconnected world powered by the Internet of Things (IoT), transportation planners and policymakers have access to unprecedented volumes of data. Today, planners and policymakers use advanced modeling and simulation capabilities to put this data to use to test new transportation solutions in digital environments that duplicate real-world conditions. For example, SANDAG is using its Activity-Based Model and “sketch planning” tools to compare the benefits of road-widening to relieve traffic congestion with the benefits of other potential improvements, such as fast rail lines or light rail systems.63

Digital twins could be used to run simulations based on real conditions on roads, highways, and toll plazas, among other facilities. They could also be used to improve air traffic management. For example, a software-enabled system called the Airport Operations Performance Predictor (AOPP) ingests a vast amount of historical and current air traffic data and uses advanced analytics to build thousands of scenario simulations. These simulations can help air traffic controllers address real problems on the ground, such as predicting on-time arrivals and departures, determining which flights and airlines to prioritize, managing resources in the event of emergencies, and more.64

Airservices Australia, the country’s government-owned provider of air navigation services, is investigating the use of a digital twin in conjunction with IoT and machine learning. The goal is to better manage conventional air traffic, whose volume is expected to double in the next 20 years, along with unmanned aerial vehicles that could soon crowd the airways. Using historic data, the organization’s Service Strategy team developed a digital twin of Airservices’ current air traffic network and started running tests to see if this could help better manage the network. Four initial proofs of concept demonstrated that the technology could enhance flight routes, improve takeoff times, and reduce delays.65

Challenges and closing thoughts

The five transportation trends discussed in this report do not constitute an exhaustive list. They simply provide a glimpse into some of the major shifts afoot across the US mobility landscape. The solutions associated with these trends are not one-size-fits-all; they will evolve in different ways in different jurisdictions.

While upcoming changes in the mobility ecosystem offer significant opportunities, governments that pursue these innovations will likely also have to grapple with issues such as data management, ethics, the prioritization of benefits, and the role of the private sector.

Managing data

The massive volumes of data available to transportation agencies will continue to grow in the coming years. By some estimates, in the AV and CV future, each car will produce more than 4,000 GB of data per day.67 This data can be used to help identify citizen travel patterns, reduce delays, and ameliorate congestion. For now, though, many cities are struggling to manage these oceans of information and extract useful insights to inform decision-making.

Moreover, most cities have yet to devise open data policies that would let them integrate across all elements of their infrastructure. Vast volumes of data remain trapped in silos, hindering efforts to develop seamless mobility solutions.68

Managing data ethics (and increasingly AI ethics)

As transportation agencies collect and analyze more and more data, questions will inevitably arise about how to use this data while ensuring security and safeguarding personal information. The debate on data governance will likely cover questions such as: Who will collect the data? How will it be stored? Who can access it? Can it be used beyond its initial purpose? Who has the right to allow additional access? Can the data be tokenized and masked? How and when should the data be destroyed?

The advent of AV technologies also opens up a debate around the potential ethical implications of cognitive technologies. Transportation agencies are still trying to draw up rules to govern accountability for the actions of these vehicles.

Beyond AVs, the problem of algorithmic bias could also make the use of AI-driven systems problematic. For instance, men and women have different mobility needs. Women more often than men tend to travel shorter distances, and practice “trip-chaining,” running household errands, picking up and dropping off children, and traveling with the elderly.69 When algorithms are used to make decisions about things such as bus routes and schedules, a lack of robust and reliable data about these mobility patterns is bound to produce skewed results.

Breaking the individual vs. system tradeoff

Another important question is whether the data available to transportation agencies should be used to optimize single trips or enhance systemwide operations that affect millions of passengers. One way to answer this question effectively is by first studying the needs of citizens. The principles of human-centered design should inform mobility decisions so new systems meet the needs of the people they’re intended to serve. It’s hard to change people’s travel habits unless you offer them appealing alternatives. The popularity of new transportation modes introduced in the last couple of decades—on-demand rentals, bikesharing programs, ride-hailing services, on-demand shuttles, e-scooters, and more—indicates that people are indeed willing to change, as long as the value proposition is compelling. Timely and ongoing feedback from citizens is essential for tailoring mobility offerings.70

Managing stakeholder tensions

Both the public and private sectors have diverse roles to play in designing a city’s seamless mobility operating system. Not every public transportation agency has the capabilities, resources, or funds to realize its mobility goals on its own. That’s where the private sector can help, providing expertise and resources that public agencies lack and, in many cases, providing essential funding. The challenge is to balance the public sector’s multidimensional role—as a strategist, catalyst/convener, regulator, operator, and more—while still effectively engaging the private sector.71

Managing the mobility divide

New mobility services could open up access to jobs, education, and health care opportunities that have historically been out of reach for many underserved communities. However, if these mobility services—that fail to reach areas most in need—are predicated on participation in the digital economy (e.g., smartphone, digital payments, credit card), or are too expensive to be viable options, the existing mobility divide may further widen. There should be a governance framework in place that allows the private sector to capture value while addressing the needs of all citizens.

Looking ahead

The need for simpler, faster, more convenient, and more sustainable transportation will likely only increase with time. So, too, will the number of innovative solutions ready to help usher in a new era of mobility befitting of the age of AI.

In a world of constant change, transportation leaders will need to be more intuitive—to sense and respond to new technology opportunities, social challenges, and citizen needs as they emerge—and more open to solutions that harness data, technology, and human experience capabilities to tackle both new and long-standing transportation challenges.

As governments and their private sector partners contemplate their next moves, they should consider the five trends that are currently reshaping the landscape and ask how these trends might inform their own journeys toward a better transportation future.

© 2021. See Terms of Use for more information.

Learn more about transportation & hospitality

-

Transportation Collection

-

The road logistics industry in India Article5 years ago

-

How are global shippers evolving to meet tomorrow’s demand? Article5 years ago

-

Creating IoT ecosystems in transportation Article5 years ago

-

Keeping London moving Article5 years ago

-

Toward a mobility operating system Article5 years ago