Serial and small M&A strategies that work for consumer products companies

4 minute read

20 August 2020

Frequent, small-sized acquisitions have proved profitable and value accretive.

The disparate fortunes of consumer products companies

Go back five years. In 2015 we saw a group of just over 200 US consumer products companies that were middle-of-the-road performers (figure 1). As our multiverse framework bears out, they were companies at a crossroads. Fast forward four years. Their fortunes have diverged substantially. About one quarter of them have significantly improved their performance and total shareholder return by enhancing the quality of their business, building their financial resources, or both. In contrast, about 20% have fallen considerably on those same dimensions and are producing negative returns for their shareholders. Some companies, both within and outside the scope of our analysis, met a worse fate—approximately 195 consumer products companies have filed for bankruptcy since January 2019,1 and 40% of these companies have done so in 2020.

Learn more

Explore the Consumer products & retail collection

Learn about Deloitte’s services

Go straight to smart. Get the Deloitte Insights app

No company wants to be on the losing end of this competitive struggle. But what is the right path for high-quality growth? While the specific strategies of individual companies vary widely, companies have always had the option to pursue growth organically or inorganically. Of course, many do both. Our analysis centers on the acquisition approach and attempts to determine its effectiveness specific to the consumer products industry.

Acquisition as a strategy for growth

To analyze the role of acquisitions in growth, we studied 1,015 global public consumer products companies that collectively were involved in 2,484 transactions over the last decade. Our initial analysis showed that consumer products companies that made acquisitions, as a group, performed better than the overall industry on profitability as well as value metrics. Most notably, the acquirers’ three-year total shareholder returns are substantially higher than the industry median over the time period.

In order to better understand what is driving this finding and clarify the contribution of acquisitions, we compared companies that made acquisitions a core part of their strategy against those that only occasionally made acquisitions. This comparison revealed two groups (figure 2):

- Serial acquirers: Companies that, on average, carried out at least one deal every year. In practice, they are mostly large food and beverage companies with market capitalizations of more than US$1 billion, located in the United States and Europe.

- Less-frequent acquirers: Companies that, on average, execute fewer than one acquisition every year. Most are smaller in size, but about 30% are large companies. They operate most frequently in either the food and beverage or apparel space and have an evenly spread geographic presence.

Which strategy works best?

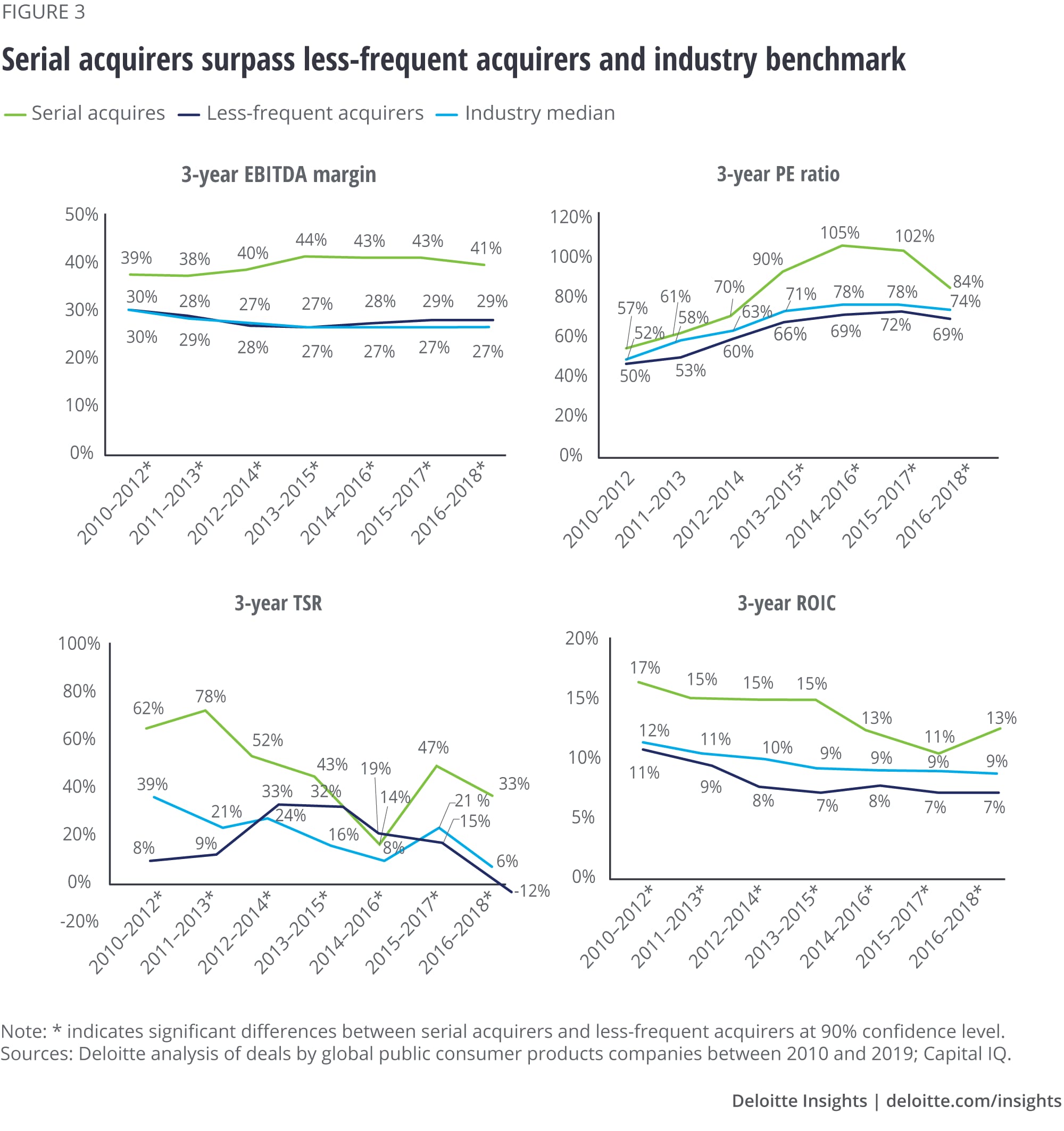

To determine how well companies that followed serial and less-frequent acquisition strategies performed, we compared their results on a series of three-year industry benchmarks tracking EBITDA, price-to-equity ratios, total shareholder return, and return on invested capital (figure 3).

Serial acquirers outperformed both the industry median and the less-frequent acquirer group on all four industry benchmarks. To confirm that serial acquirers’ performance wasn’t due solely to their large size, we compared only large companies in each group. We found that serial acquirers outperform the group of large-company infrequent acquirers on three-year total shareholder return, a success metric used in the initial multiverse analysis. The result provides further evidence that the credit for success likely lies in the unique serial acquisition strategy.

What makes serial acquirers successful?

There are likely many elements at play for a given consumer products company, but we see three primary factors that stand out in our analysis of serial acquires:

They buy small

Most deals made by serial acquirers involved buying small companies with an average transaction size of only US$22 million. These deals do come at a premium, so the choice isn’t obvious. On average, the purchase prices were 6.5x the revenue for smaller targets versus 1.2x for large. Yet, in absolute terms, each small deal required only around 1/20th of the investment needed for large deals. Smaller capital outlays meant the downside risk of each individual deal was contained.

They buy to extend and explore

Instead of trying to further grow share in their existing offerings and markets, serial acquirers often bought companies that helped them try new things. These acquisition targets often had different product or service offerings or access to parts of the market not served by the acquiring company. For example, Anheuser Busch was able to add breadth to its portfolio through strategic acquisitions of unique craft and European import brands, including Goose Island, Blue Point, 10 Barrel, Elysian, Devils Backbone, Golden Road, and Four Peaks. Serial acquirers also sought new technology or business capabilities to help them address emerging industry opportunities. And the intangible in-market experience held by these target companies could arguably be harder to obtain through organic investment.

They get better at integrating

If practice makes perfect, serial acquirers have much more experience integrating acquisitions. They have learned how to accommodate small, innovative businesses into their portfolio without disrupting the very value they wanted to capture in the process.

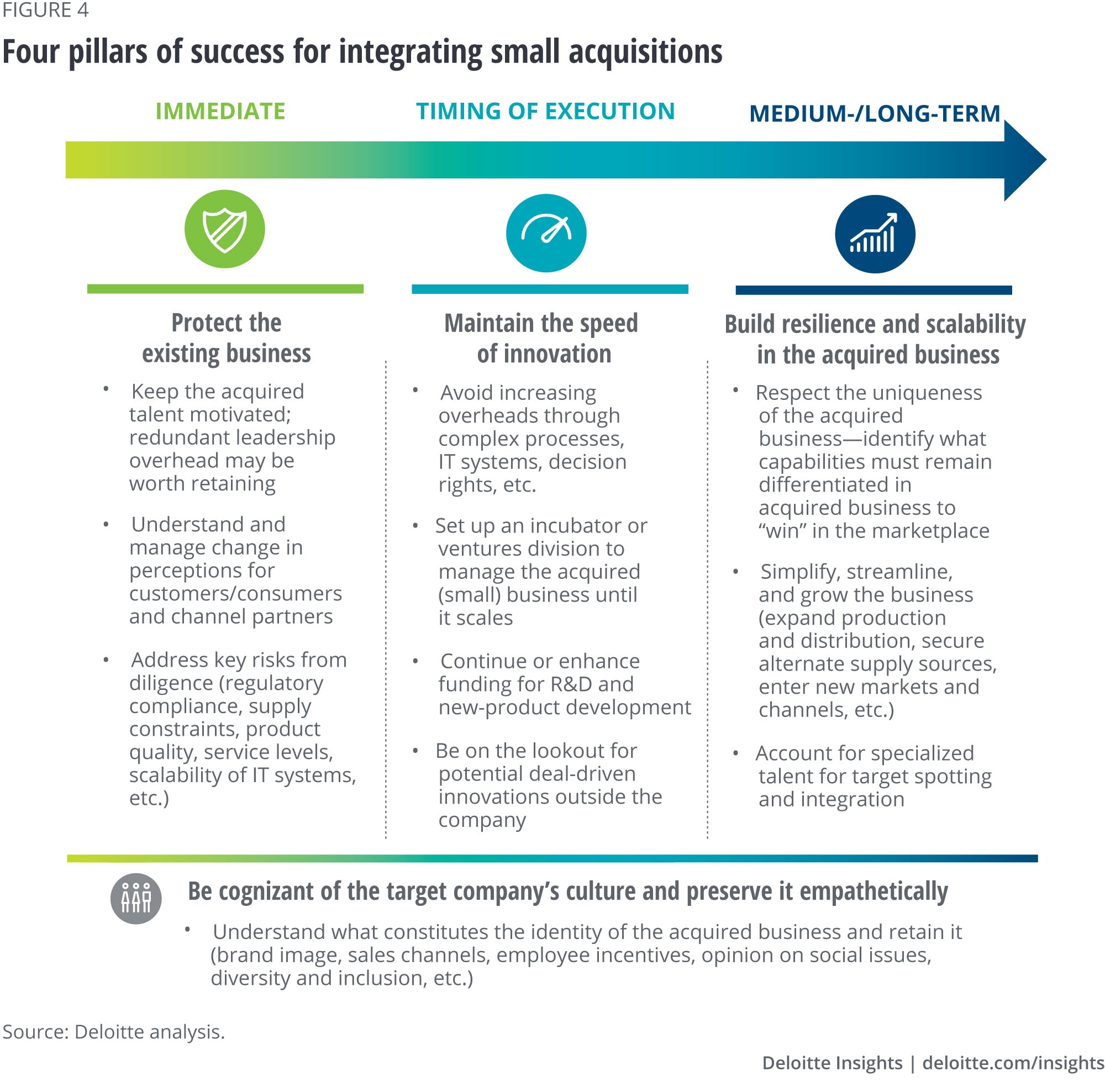

Companies can tap into the four pillars to integrate acquisitions more successfully (figure 4).

This moment in time

The outbreak of COVID-19 poses perplexing challenges for the consumer products industry and many others. The dual safety and financial concerns resulting from the pandemic are causing consumers to change their buying behavior and shift to new, often digitally mediated channels.2 As a result, many smaller companies are facing liquidity issues and are struggling to manage their formerly high-growth premium products. It is a time of both challenge and opportunity. Consumer products companies should quickly adapt their offerings and build out new capabilities to meet the moment. Larger companies, with balance sheets to support the strategy, can follow serial acquirers’ approach and buy small, innovative companies to solve for the new, unmet needs. Smaller companies, which could be potential targets, should consider how they would be positioned to help an acquirer extend into and explore new offerings and markets. Regardless, the most successful deals will likely be those integrated through a process that protects the existing business while maintaining the speed of innovation and respects the culture while scaling out for value capture.

© 2021. See Terms of Use for more information.

More on Consumer products

-

Small positive signs in the consumers’ dual-front crisis Article4 years ago

-

The future is coming ... but still one day at a time Article4 years ago

-

ConsumerSignals Interactive5 days ago

-

Augmented shopping: The quiet revolution Article5 years ago

-

Retail distribution Collection