The inclusion imperative for boards Redefining board responsibilities to support organizational inclusion

20 minute read

02 April 2019

Corporate and nonprofit board members have an important role in building an inclusive environment that drives performance and financial results.

Yes, boards do matter for inclusion

Corporate and nonprofit boards of directors—spurred by a mix of persuasive research; pressure from shareholders, employees, customers and business partners; and their own intuitive sense of what’s right—have been working for years to improve diversity in their own ranks. For example, the percentage of women on Fortune 500 boards rose to 22.5 percent in 2018, up from 15.7 percent at the start of this decade. People of color on Fortune 500 boards increased from 12.8 percent in 2010 to 16.1 percent in 2018.1

Defining diversity and inclusion

While diversity and inclusion may be inextricably linked, they are not one and the same.

- Diversity refers to the presence of people who, as a group, have a wide range of characteristics, seen and unseen, which they were born or have acquired. These characteristics may include their gender identity, race or ethnicity, military or veteran status, LGBTQ+ status, disability status, and more.

- Inclusion refers to the practice of making all members of an organization feel welcomed and giving them equal opportunity to connect, belong, and grow—to contribute to the organization, advance their skill sets and careers, and feel comfortable and confident being their authentic selves.

The main difference between the two is that diversity is a state of being and is not itself something that is “governed,” while inclusion is a set of behaviors and can be “governed.”

Therefore, this report emphasizes the board’s role in governing inclusion. This by no means diminishes the importance of diversity and the need to continue to drive progress. On the contrary, boards should engage in conversations with management about improving diversity, and this in itself is an inclusive practice.

There’s little debate that driving diversity should continue to be an important priority for all organizational leaders; nevertheless, it is becoming increasingly evident that focusing on diversity without also focusing on inclusion is not a winning strategy.2 Management teams—their efforts often led by chief diversity, inclusion, or human resources officers—have started to recognize this, and some have taken concrete action to develop and execute inclusion strategies that go beyond diversity to create inclusive cultures at their organizations.

Inclusion, however, is an issue whose importance touches leaders beyond the C-suite. So, what can boards do to further promote and solidify an inclusive culture at the organizations they oversee? A great deal, it turns out. Although boards of directors remain one step removed from the C-suite’s execution focus, they have a meaningful role to play in building an inclusive enterprise, and they can govern in ways that put C-suites and organizations on a positive path.

Why should boards care about inclusion?

“The board setting an example is important,” states a director of a Fortune 500 industrial products manufacturer. “If the board is not both diverse and inclusive, it lacks credibility with management”—as likely as well with investors, customers, employees, and other stakeholders.

Yet boardroom conversation around the board’s influence over inclusion is often scarce. A review of some charters for board committees in areas with potential diversity and inclusion implications—such as nominating and governance, human resources, and compensation—revealed that while more than half mentioned diversity and inclusion, these references most often only pertained to demographic composition (diversity). A small minority of these charters made direct references to the board’s oversight of inclusive organizational culture, practices, or strategy (inclusion).3 Additionally, while many boards use tools such as board competency matrices in their succession planning efforts, most of these tools do not provide detailed insight into board members’ experiences and capabilities, including their experience or capability in practicing inclusive behavior.4

Qualitative research further reinforces the need for additional board focus on inclusion. Interviews with board members and executives of organizations across the marketplace reveal that a large majority of boards may not consider diversity and inclusion as separate concepts. Indeed, most boards’ current efforts in these areas focus mostly on diversity.5

Boards have an interest in encouraging inclusion as well as diversity, however. The uplift organizations receive from having an inclusive culture, and not just a diverse workforce, is substantial. Where an inclusive culture exists, employees are much more likely to see themselves as part of a high-performing organization in which teams collaborate and consistently meet client and customer needs. Teams also perform better when they are both diverse and inclusive—there is less groupthink and more innovation.6 In fact, the board, as a team, can also exemplify this pattern. When comparing low- and high-performing boards, high-performing boards are more likely to exhibit gender balance and inclusive behaviors.7

These outcomes of inclusion can translate into financial results. When operating under an inclusive culture and inclusive talent practices, organizations generate up to 30 percent higher revenue per employee, are more profitable than their competitors,8 and become eight times more likely to achieve positive business outcomes.9

In short, because diversity alone does not ensure that organizations are able to bring a wide variety of insights, life experiences, and perspectives to bear on their challenges and opportunities, boards should also value and promote inclusion as a separate yet connected priority.

It is time for boards to recognize both their potential for influencing inclusion and their responsibility to do so, not only for the sake of their own organizations and employees but, where relevant, also for the sake of their various stakeholders. “Shareholders ask about diversity and inclusion because they know [diversity and inclusion] add to long-term shareholder value,” says Kosta Kartsotis, chairman and CEO, Fossil Group. Furthermore, as markets and customer preferences shift, boards and executives benefit from recognizing that prioritizing the inclusion of diverse customers and stakeholders is key to staying competitive in the marketplace.10

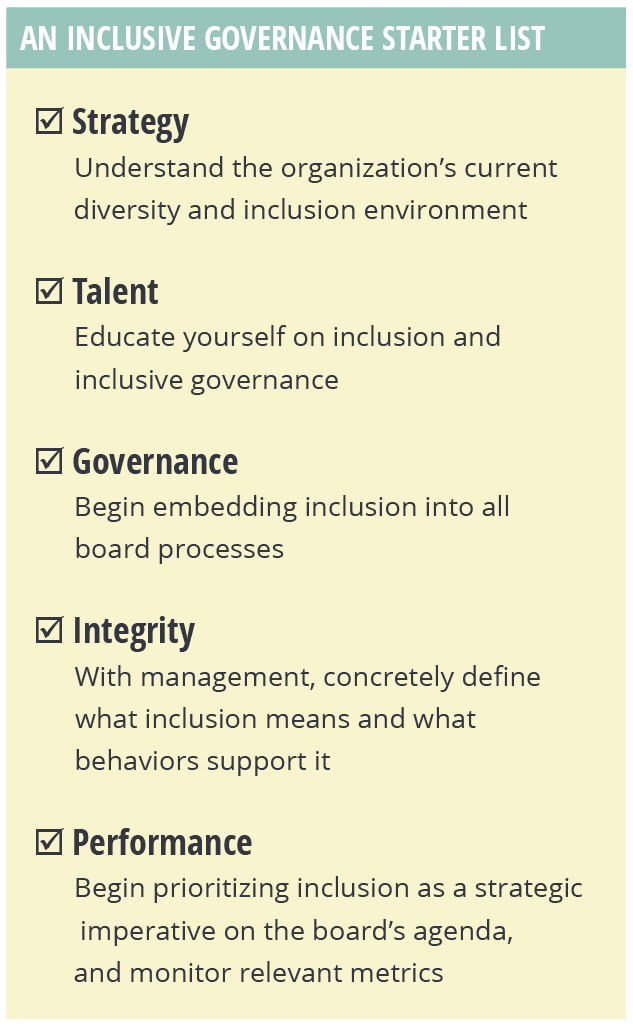

How can boards shift into an inclusion governance mindset? While it may seem an amorphous undertaking, it is possible for boards to chart a clear way forward that embeds inclusion into every facet of the organization’s work, workforce, and workplace.

Influencing inclusion: The board’s responsibilities in five key areas

“It all starts at the board to set the tone for inclusion as a priority both internally and externally.”—Ken Denman, governance & nominating committee chair, Motorola Solutions

Past research reveals, and our interviews confirm, that boards of directors traditionally own five key areas of organizational oversight: 11

- Strategy

- Governance

- Talent

- Integrity

- Performance

As these responsibilities evolve to account for changes in regulations, the business environment, and society in general, the role boards play in influencing inclusion within each of these five areas is becoming even more important.

Strategy

“Boards don't run the company—they govern. Boards can ask questions about the culture, whether or not it’s inclusive, and how to support an inclusive culture with the business strategy. That's the board's job.”—Director, various Fortune 500 organizations

In the most inclusive organizations, inclusion is seen by all employees as critical to business strategy.12 However, building an inclusive culture does not happen overnight. Boards can expedite progress by helping management define a common vision for what inclusion means and embed that vision directly into the business strategy.

In defining the vision for inclusion, the board and management will want to consider how individual, organizational, and societal biases may interfere with reaching inclusion goals. For example, if individuals with different identities are hired or promoted, or leave the organization, at unequal rates, what could this indicate about the level of inclusion employees might experience at the organization? If community partners and vendors do not have inclusive policies within their own firms and operations, what signals might a partnership or contractual relationship send to employees and the marketplace? If products and services are not designed to meet the needs of a diverse set of customers, how might this affect the company’s bottom line?

Additionally, the definition of inclusion should tie into the organization’s objectives, vision, mission, and strategy, perhaps using language directly from the organization’s mission statement. The tighter the alignment, the more deeply the inclusion message will resonate with board members, executives, and the broader workforce, and the more likely it will be to elicit behavior changes that contribute to a more inclusive culture.

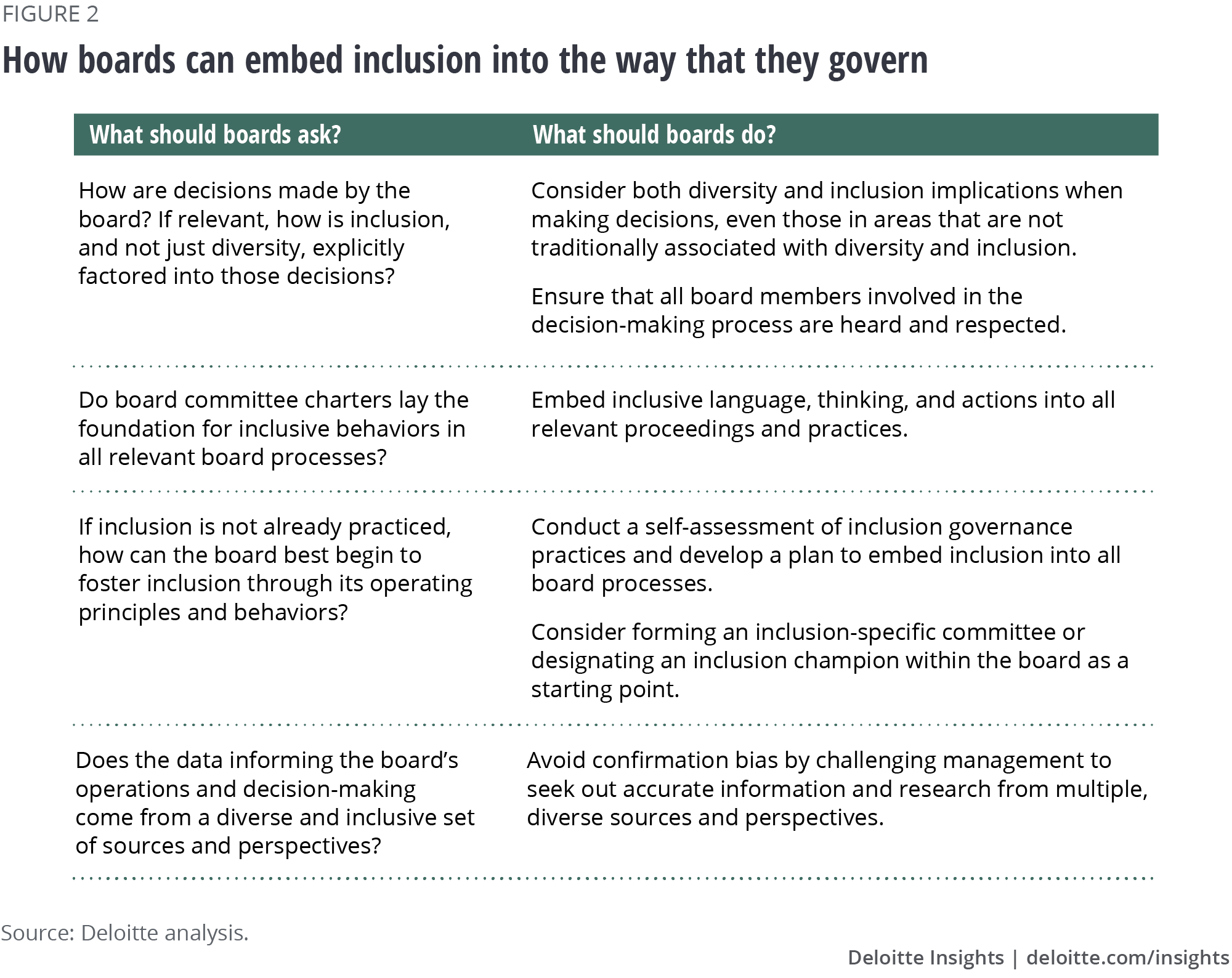

Governance

“To truly embody and govern inclusion, the board should reflect the diversity of [the organization’s] customer base in its composition, create an inclusive culture within the boardroom itself, and integrate inclusive thinking and behaviors into all of the ways that the board operates.”—Trudy Bourgeois, founder and CEO, Center for Workforce Excellence

It is incumbent upon boards to govern and operate with an inclusion lens—particularly as they preside over shifts in strategy, advise on major investments, and monitor risks. Boards that demonstrate inclusive governance practices integrate inclusive thinking in all board proceedings and understand how their actions and decisions may lead to inclusion-related implications. Consider these potential boardroom scenarios:

- As an example of how board members interact, when having heated discussions or discussing sensitive topics in board meetings, are all board members able to contribute equally and do they feel welcome to do so? If not, how can the board operate differently to create an open and authentic environment for all of its members?

- As an example of governing business strategy, when the board is helping to evaluate whether to acquire another organization, does the board consider how the target’s level of inclusion—informed in part by the diversity of its workforce—compares to the organization’s own? If the target is not as advanced in these areas, what risks could the organization thereby assume, and how can they be mitigated?

Similarly, inclusive board committees consider inclusion as a key element when crafting and executing their separate charters, perhaps going so far as to explicitly detail expectations for operating in an inclusive manner.

As a first step in holding itself accountable for inclusive governance practices, boards may even consider establishing a committee, temporary or permanent, focused specifically on inclusion. This inclusion committee’s mandate would be to elevate inclusion’s visibility in the boardroom and promote inclusive governance practices across all board committees and procedures.

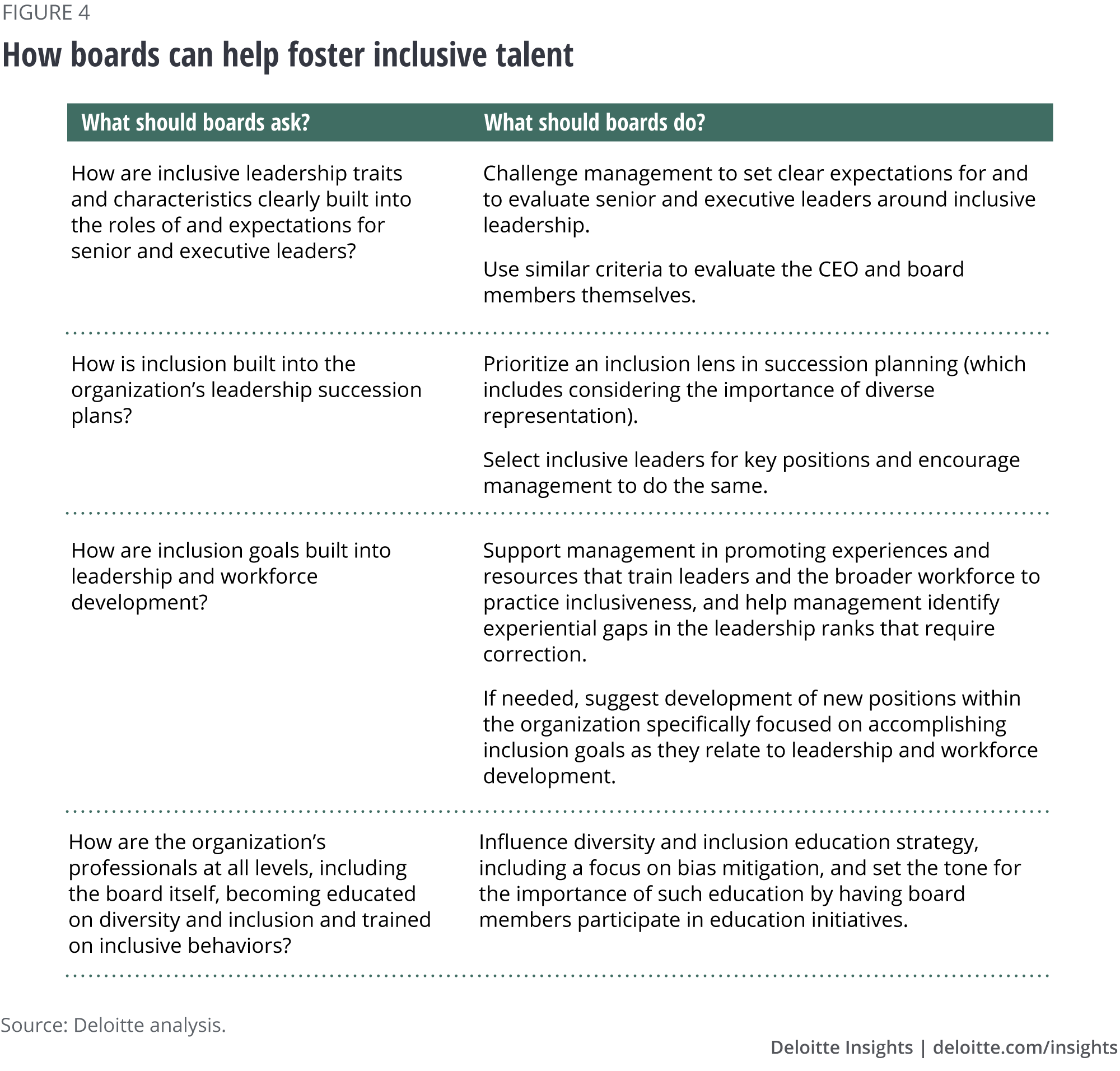

Talent

“Where the board can influence inclusion is in asking questions like, ‘What is [management] doing to ensure that people at all levels and of all backgrounds have an opportunity to be developed and mentored into the senior management levels?’”—General Lester Lyles (USAF retired), Chairman, USAA and director, General Dynamics and NASA

It is often said: Tone starts at the top. Boards can best advance the inclusion agenda not just by embodying inclusive leadership traits among their own members, but also by holding management accountable for developing the organization’s talent—executives, managers, and front-line employees—into inclusive leaders.

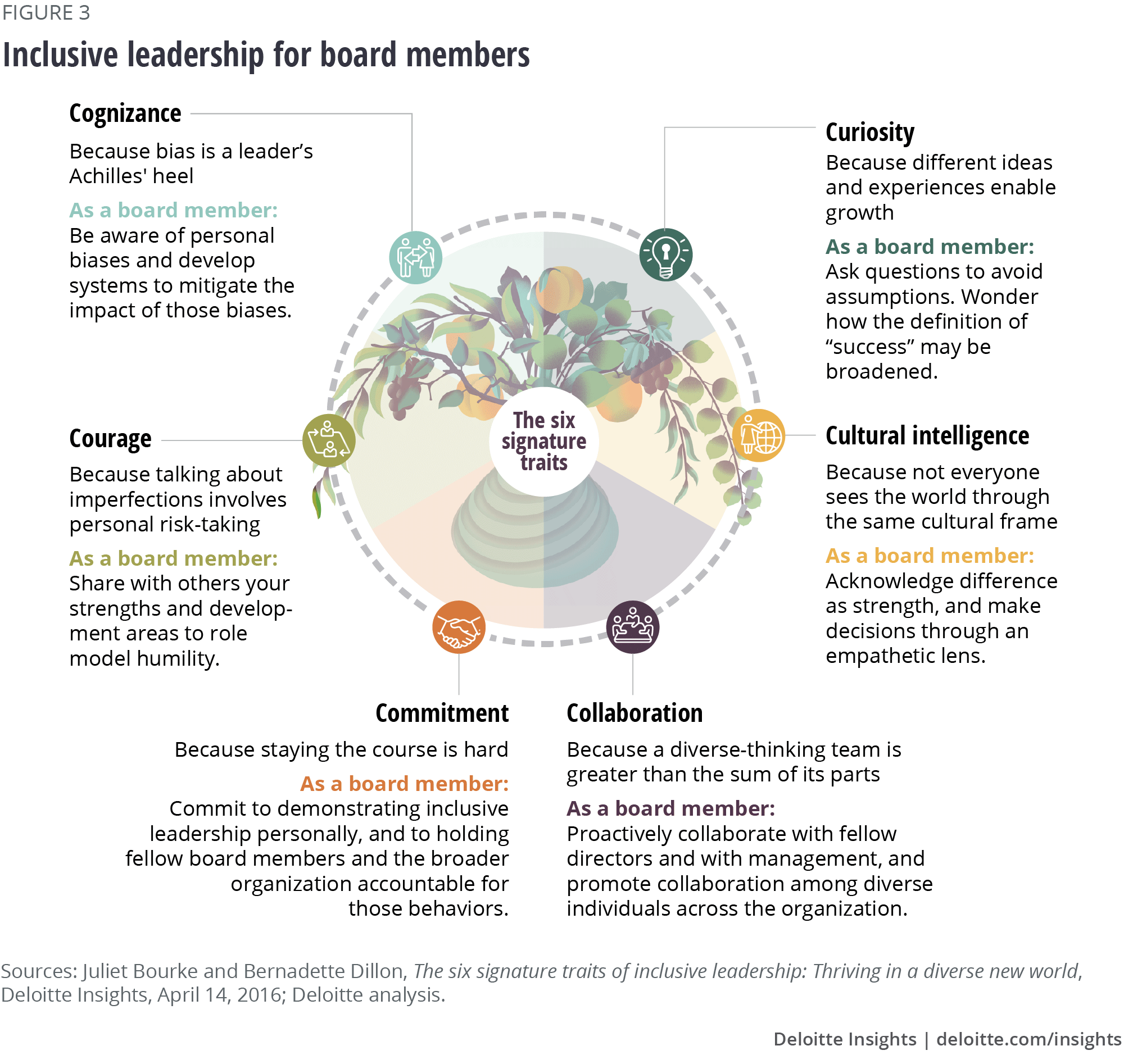

In general, inclusive leaders recognize and value people and groups based on their unique characteristics and learn to mitigate biases stemming from stereotypes. They also leverage the thinking of diverse groups of individuals for smarter ideation and decision-making, reducing the odds of being blindsided by up to 30 percent, increasing innovation by up to 20 percent, and fostering a sense of trust.13

Deloitte has identified six signature traits of inclusive leadership: commitment, courage, cognizance, curiosity, cultural intelligence, and collaboration (figure 3).14 Board members can use these traits as a starting point for modeling inclusive leadership in all of their daily interactions and behaviors, both inside and outside of the boardroom.

To promote a pipeline of inclusive leaders, boards can encourage management to set these same six traits as formal competencies for senior leaders by embedding them into the organization’s performance management, professional development, and succession planning processes. “Organizations would rarely promote business leaders who don’t demonstrate a level of financial knowledge, and this same thought process should be applied for demonstration of inclusive behaviors,” says Trudy Bourgeois, founder and CEO of the Center for Workforce Excellence. “Inclusion is, in fact, a business imperative. So, if you are being considered for a top leadership position, then you should have already demonstrated competency as an inclusive leader.”

Finally, boards have a role in challenging management to cultivate inclusive leadership skills throughout the enterprise. Employees see inclusion as one of the most important factors in deciding where to work, and they want inclusion to be fundamental to their daily work experiences.15 To achieve this, boards, as well as middle management and other employee groups, also play a critical part in championing and driving inclusive behaviors and practices. Collective accountability from all employees for fostering an inclusive culture is key to a successful and sustainable long-term inclusion strategy.

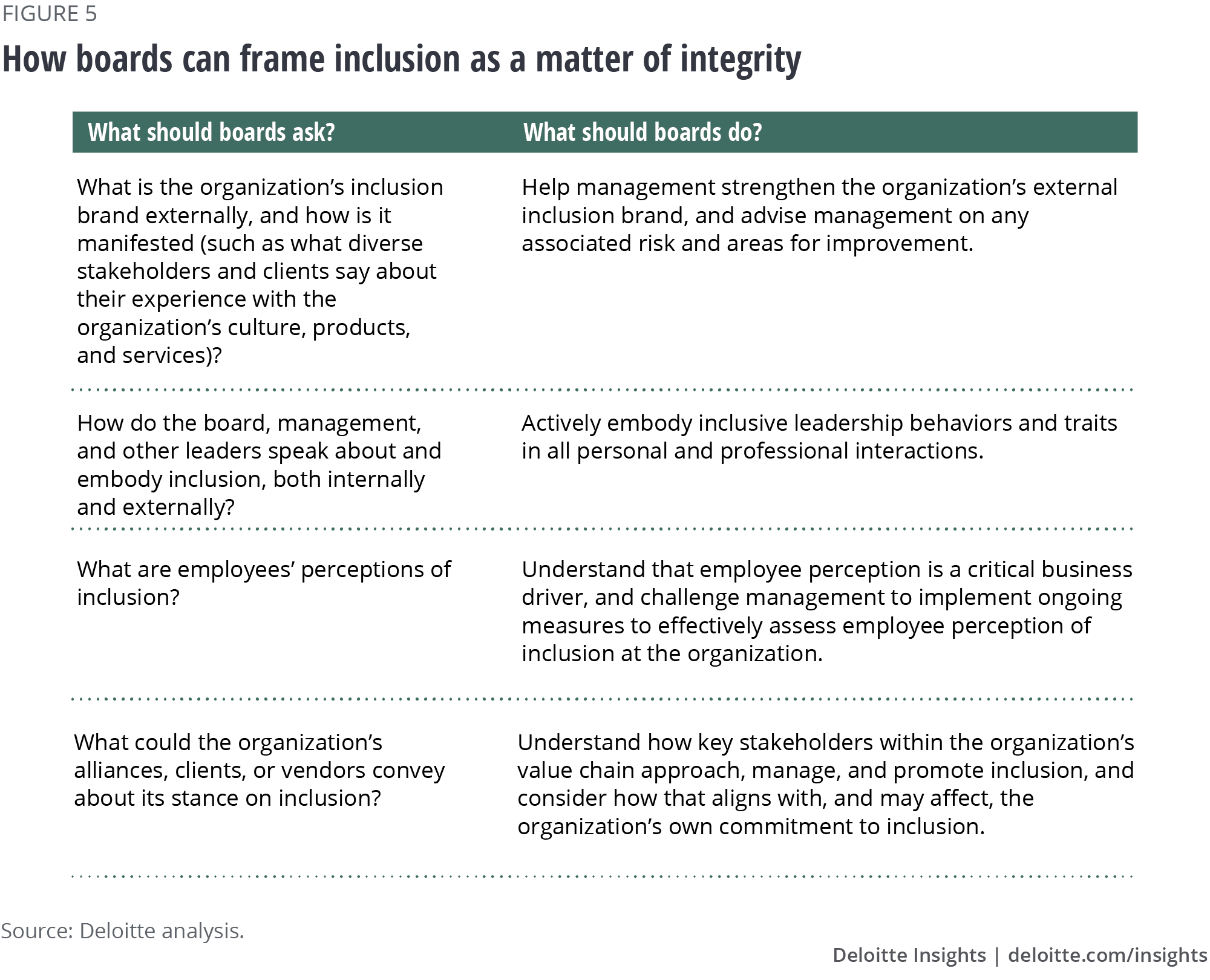

Integrity

“When boards think and act inclusively, it sends a very clear message [about] what's important to the company.”—Billie Williamson, director, Kraton Corporation, Cushman & Wakefield, and Pentair

By setting the tone for inclusion and prioritizing it both internally and externally, a board has an opportunity to hold itself accountable for maintaining the integrity of its inclusion vision and to improve public perception of the organization and its brand.

Board members can advance a commitment to inclusion by leveraging their unique social and political capital to be a champion and role model, while looking for opportunities to directly acknowledge and formally promote their commitment to inclusion: in communications to shareholders, in public appearances, in interviews and conference presentations, and informally in networking and professional conversations.

Elsewhere, the board can guide management to consider how the organization itself talks about or represents inclusion in communications—whitepapers, press releases, marketing materials—and what the organization’s people say in the media. Finally, the board can encourage management to consider the integrity of the prospective partner’s inclusion vision when entering into alliances with other organizations or contracts with supply chain partners.

Performance

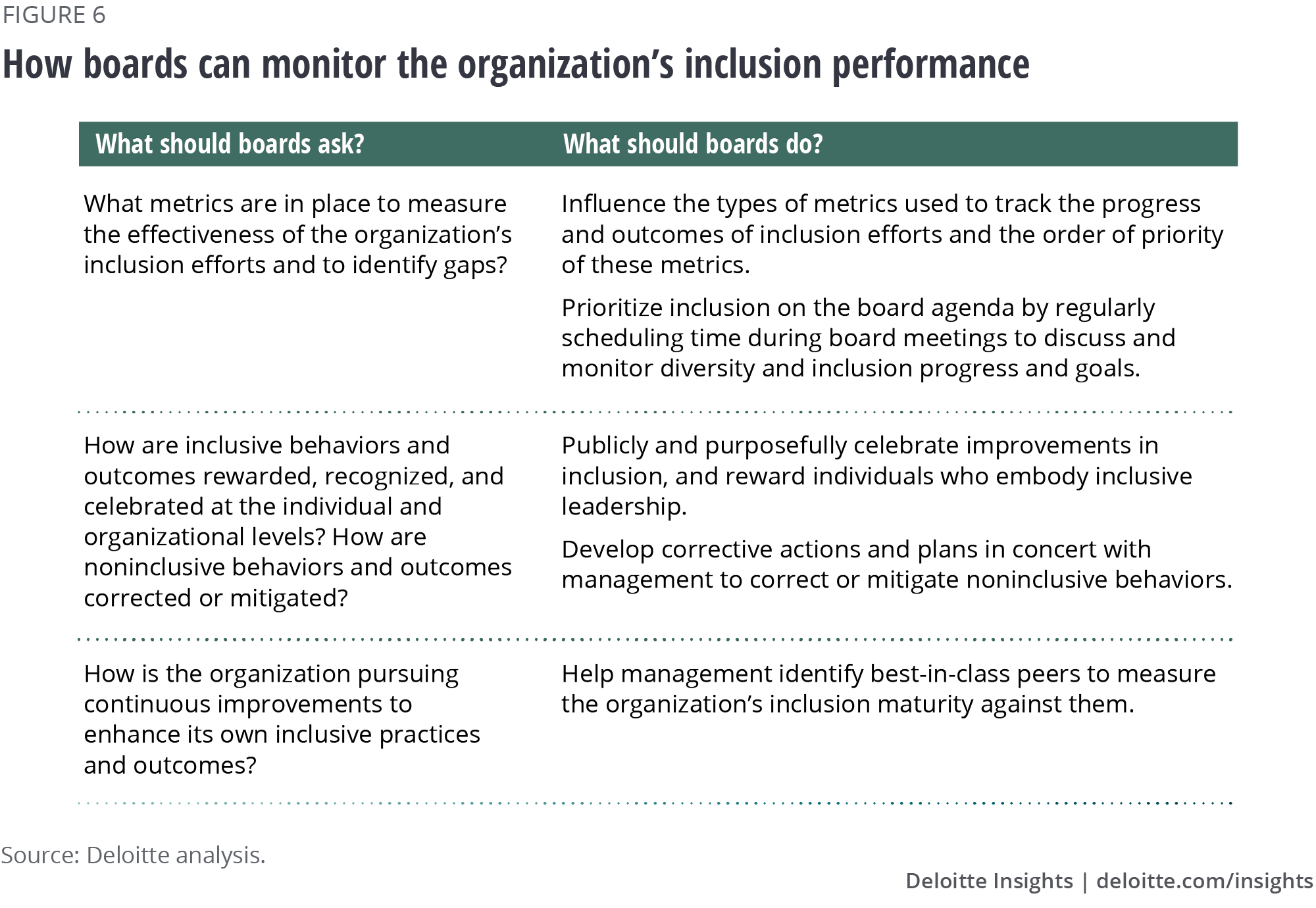

“[Driving] inclusion has to be a shared responsibility, but the roles are different. Management executes and advances the [inclusion] mission, and the board holds management and the organization accountable to that mission.”—Sheila Penrose, chairman, Jones Lang LaSalle Inc. and director, McDonald’s Corporation

Transformations of any kind are subject to fatigue and failure unless someone is held accountable for outcomes. Building and maintaining an inclusive culture is no exception, which requires the board to hold the entire organization—management, all employees, and the board itself—accountable.

It is the board’s role to monitor diversity and inclusion metrics at a high level, while requesting that management collect and analyze the relevant data (see the sidebar, “Measuring diversity and inclusion”). For instance, roughly 32 percent of respondents to a 2017 human capital survey indicated their organizations do not measure or monitor diversity and inclusion in their recruiting efforts.16 Boards can play a significant role in closing the gap in this as well as in other areas. With data, the board can not only track the organization’s progress, but also guide its own efforts to operationalize the board’s multifaceted role in embedding inclusive thinking and behavior in strategy, talent, governance, integrity, and performance.

Measuring diversity and inclusion

To measure diversity, organizations can track the rate at which they hire and employ people in various demographics, which may be characterized by gender identity, race or ethnicity, military or veteran status, LGBTQ+ status, or disability status, among other traits.

To measure inclusion, which can often be more challenging, organizations can compare the rates of retention, promotion, and attrition among the various demographics used to track diversity. Beyond measuring these factors, organizations should go further to understand the reasons for any differences and whether a lack of an inclusive culture is an underlying cause. Additionally, organizations can field ongoing pulse surveys that ask employees about their perceptions of the work environment, levels of engagement, and overall employee experience.

Boards can enhance management’s accountability for progress in inclusion by purposefully rewarding good inclusion performance. While 78 percent of respondents to the aforementioned survey believed inclusion to be a competitive advantage, a mere 6 percent of respondents indicated that their organizations actually tie diversity and inclusion outcomes to performance management and compensation.17 Therefore, at the most senior levels of the organization, boards should consider linking some percentage of performance-based compensation to meeting inclusion objectives. For the rest of the workforce, boards may also encourage management to develop ways to hold all employees accountable for inclusive behaviors. These may include tactics such as developing formal performance expectations or creating monetary incentives, awards, or recognition programs.

Finally, boards should also evaluate their own performance in individually embodying inclusive leadership traits and collectively conducting inclusive governance practices. This evaluation can be incorporated into annual board self-assessments or, if a board decides to form an inclusion-specific board committee, through the inclusion committee members’ due diligence.

Where organizational inclusion objectives are not being met, the board can work with management to develop plans for corrective action. Such plans may include deployment of additional awareness and education for areas in need of improvement, or removal of employees who exhibit actions contrary to an inclusive culture.

What can boards do now?

“The endgame is inclusion, and that is how you come up with better results and better solutions for shareholders.”—Director, Fortune 500 petroleum company

Creating and sustaining an inclusive culture may be one of the most difficult challenges an organization’s leadership, including its board, can undertake. Unlike engineering a better product or rooting out process inefficiencies, it can require teaching people how to rethink or eliminate deeply ingrained and even subconscious perceptions and behaviors. But the potential rewards are too dramatic, the moral imperatives too strong, and the risks of failure too great for boards not to lead on this issue.

The concepts outlined in this report are not intended to serve as a one-size-fits-all solution. Each organization should adapt its inclusion governance approach to reflect its own characteristics: its size and geographic reach; the complexity of its organizational structure; whether it is public, private, or nonprofit; the industry in which it competes; its current levels of diversity and inclusion maturity; and the size and complexity of its board.

Nonetheless, taking steps to cultivate inclusion in the board’s five key areas of responsibility can help lay a path for boards to:

- Articulate the current state of the board’s approach to inclusion governance

- Assess that approach against leading practices

- Identify what can be done to achieve inclusive governance goals

- Implement the changes necessary to accomplish those goals

By setting an example of inclusion in the boardroom, by advocating for an inclusive culture both internally and externally, and by holding management accountable for taking concrete measures to embed a culture of inclusion throughout the enterprise, boards can move a needle that’s been advancing far too slowly for far too long.

Appendix: Research methodology

The idea that boards of directors have a role in governing inclusion, or in promoting an inclusive culture within their organizations, has not been widespread across the marketplace. A recent and thorough review of existing governance, diversity, and inclusion literature uncovered no material works on the subject. The topic’s novelty was further confirmed by an analysis of board committee charters, which found little to no direct mention of inclusion governance as a board responsibility. Similarly, interviews with current governance, diversity, and inclusion thought leaders uncovered little previous or current work in board governance of inclusion, though most demonstrated support for the concept.

Deloitte Governance Framework

This report outlines five key areas that boards can influence in governing inclusion. The recommendations are shaped both by Deloitte’s understanding of the traditional responsibilities of corporate boards and by the insights of seasoned board members and governance leaders. They represent an evolution, through an inclusion lens, of the five key board governance elements, where the responsibility of the board is typically heightened, first introduced in Framing the future of corporate governance: Deloitte Governance Framework.18 This framework and its elements are largely supported by existing governance literature.

Interviews

As part of the research for this report, the authors interviewed 14 executives and board members, as well as two diversity and inclusion subject matter experts. These interviewees currently sit on the boards of or hold executive management positions at 45 organizations, 19 of which are Fortune 500 companies (data collected via BoardEx).

The interviewees were identified either by Deloitte professionals or by board members at the organizations with which they are or had been associated. All of the interviewees met one or more of the following criteria:

- The individual currently serves or had served on the board of a Fortune 500 company.

- The individual is or had been an executive at a Fortune 500 company, where he or she has or had close ties to or knowledge of governance matters.

- The individual’s organization has demonstrated leadership in diversity and inclusion efforts, with accomplishments such as receiving a nomination from the National Association of Corporate Directors NXT initiative annual awards, which recognizes boards of directors that promote greater diversity and inclusion.

- The individual has demonstrated expertise in the areas of governance, diversity, and inclusion.

The interviews were conducted by phone and were semi-structured. They covered questions that included, but are not limited to, how the interviewees’ organizations define diversity and inclusion; how the interviewees saw the role of the board in governing inclusion; and which inclusion governance practices already were in place at their organizations. Two researchers reviewed the transcripts to capture key themes.

Read more on topics around Diversity and Inclusion

-

Value of Diversity and Inclusion Collection

-

Fighting workplace gender bias Article6 years ago

-

The diversity and inclusion revolution Article6 years ago

-

Diversity and inclusion Article7 years ago