Monetary policy in emerging economies A reversal in the cards?

8 minute read

10 May 2019

Weakening global growth prospects and the Fed’s pause in monetary policy tightening have resulted in emerging markets either halting tightening cycles or reversing direction. However, the recent rally in oil prices and risks associated with some emerging market assets could complicate monetary policy decisions.

In February 2019, the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) cut its key policy rate by 25 basis points (bps) and changed its stance to “neutral” from “calibrated tightening.”1 That and a further 25 bps cut in April marked a remarkable turnaround in monetary policy from the previous year when the RBI had hiked interest rates to counter rising inflation. The RBI is not a lone wolf in shifting its monetary stance. A few other central banks have followed suit—there were more rate cuts than rate hikes among a group of 37 emerging market central banks at the end of February and March, according to a Reuters report.2

A pause by the United States Federal Reserve (Fed) in its rate hike path3 has enabled central banks in emerging economies to go easy on the tightening cycles they started (mostly in 2017–2018). The Fed’s tightening since December 2016 had led to strains on liquidity inflows into emerging economies due to their narrowing interest rate differentials with the United States.4 These concerns have eased in recent months with the Fed keeping rates on hold for now. Consequently, key emerging market currencies have performed better this year than in 2018. And as inflation eases, central banks in these economies are expected to shift their focus to the slowing economic growth. However, a protracted rise in oil prices and risks concentrated in Argentina and Turkey could complicate monetary policy decisions across many emerging market economies.

Interest rate differentials with the United States have stabilized

Between December 2016 and December 2018, the Fed pushed interest rates up by 200 bps. This led to a reduction in interest rate differentials with emerging economies. For example, the differential between India’s repo rate (policy rate) and the upper limit of the federal funds rate fell from 575 bps in November 2016 to 425 bps in March 2018; it has fallen further since then, but more due to two rate cuts by the RBI this year. Similarly, the difference between China’s official rate and the upper limit of the federal funds rate has fallen by 200 bps since November 2016. A similar trend is visible for key emerging economies other than Argentina and Turkey where central banks have been forced to raise rates steeply to prevent accelerating inflation and a run on their currencies.

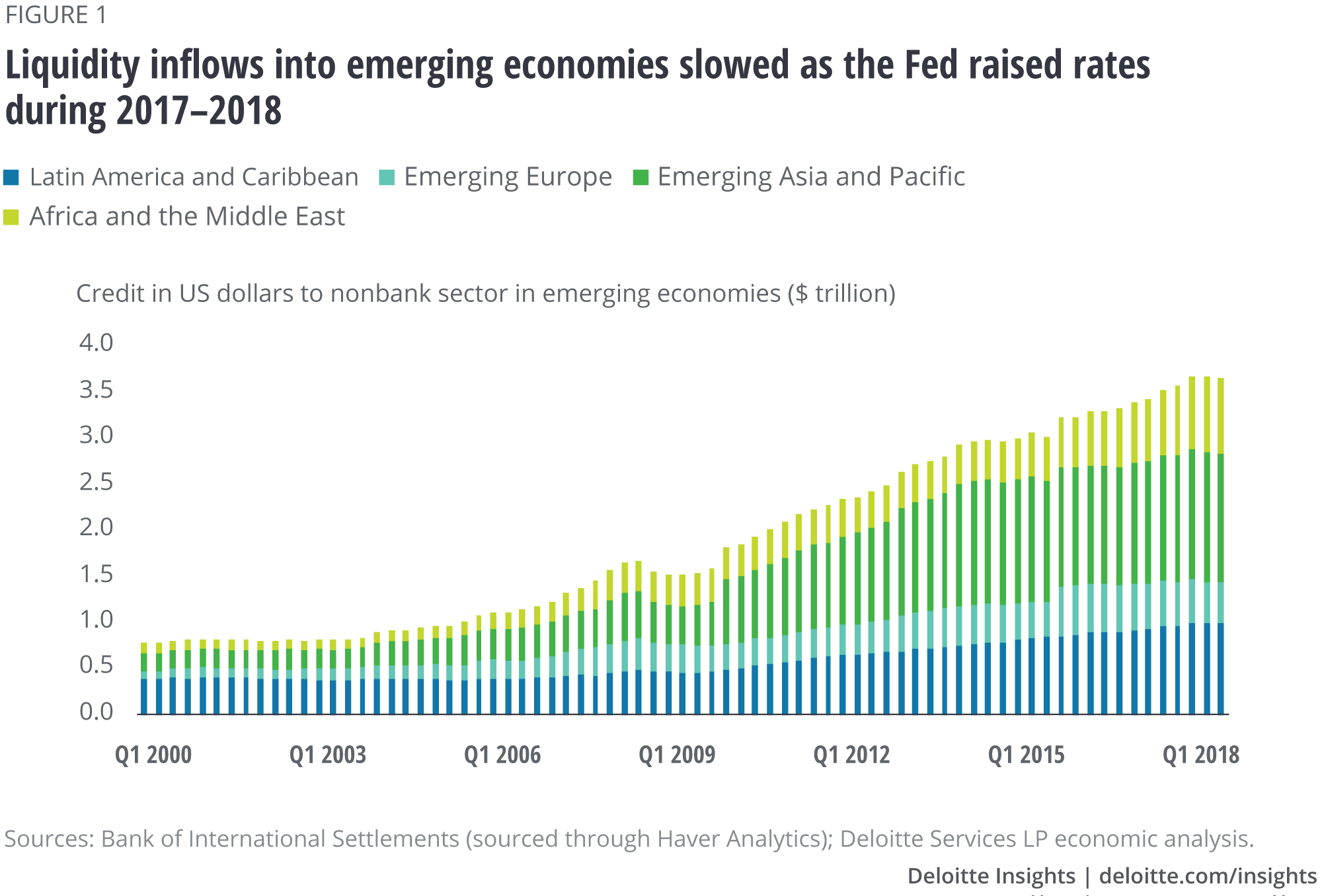

The decline in interest rate differentials had an impact on liquidity flowing into emerging economies—the pace had already slowed post 2014 due to worries about Fed tapering—with credit in US dollars to the nonbanking sector in emerging economies declining by 0.4 percent in Q3 2018 (figure 1). With the Fed, however, pausing its rate hike cycle since December 2018—Deloitte’s economists, in their baseline scenario, expect only a further 25 bps hike this year5—interest rate differentials between the United States and emerging economies have stabilized, thereby putting a lid on liquidity outflows. In China, for example, rising equity markets have attracted strong inflows, while in India, net portfolio inflows have turned positive since January.6 The Institute for International Finance expects this recovery in inflows into emerging economies to continue into 2020.7 For central banks in emerging economies, this has come as a great relief.

Currency recovery means something less to worry about

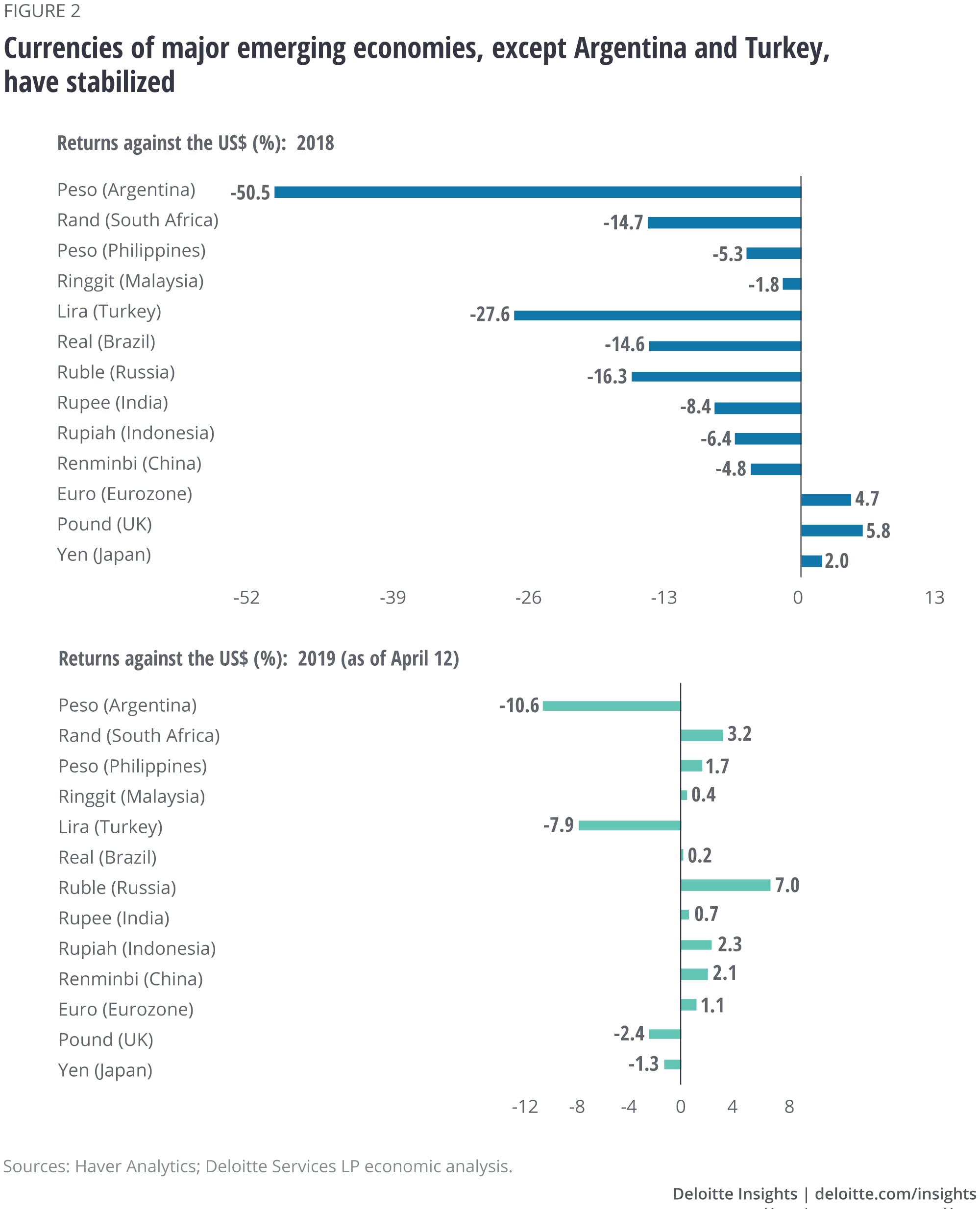

Emerging market currencies have recovered some ground this year after suffering in 2018 (figure 2). The Russian ruble, for example, is up by 7 percent so far this year (as of April 12) against the US dollar, despite continuing sanctions on the economy; the currency had shed about 16.3 percent against the greenback in 2017. And in Brazil, although much of the economy’s fortunes hinges on the fate of reforms, the real appears to have stabilized this year after weakening by 14.6 percent to the US dollar in 2018.

For oil importers such as India, easing oil prices in the final quarter of 2018 likely helped in relieving the pressure on external balances, enabling the rupee to claw back to some extent. Interest rate hikes in 2018 have also helped some currencies. In Indonesia, for example, Bank Indonesia raised rates five times in 2018 by a total of 175 bps, thereby ensuring that the rupiah did not fall by as much as (say) the Indian rupee during the year. The Turkish lira and the Argentinian peso, however, do not follow the above pattern. After a 50 percent decline against the US dollar in 2018, the peso is down again this year as investor confidence in the country hasn’t returned.8 And in Turkey, the lira continues to weaken as an economic contraction adds to the pain of diminished central bank credibility.9

A breather from soaring prices

Inflation has eased in recent months in key emerging economies. In the Philippines, for example, headline inflation fell from more than a nine-year high in September 2018 to 3.3 percent in March. In India, inflation has nearly halved from levels witnessed in the first half of 2018 (figure 3). Even in Turkey, inflation eased from a high of 24.5 percent in September 2018 to 19.7 percent in March. There are two notable exceptions—Russia, where inflation has been edging up this year (5.3 percent in March), and Argentina, where inflation has shot up (51.3 percent in February) due to a breakdown in central bank credibility and a consequent plunge in the peso.10

There are three likely causes of declining inflation in key emerging economies. First, global oil prices fell sharply from October 2018 to January 2019 after rising by an average of 38.5 percent year over year between January and October of 2018. Second, the lagged impact of monetary tightening during 2017–2018 has also pushed inflation down, although core inflation is still relatively high in countries such as India where it is mainly lower food prices that are impacting inflation. Finally, currency weakening across emerging markets has likely run its course and this has put the brakes on imported inflation this year.

Slowing economic activity is a concern

In 2018, China’s economy grew by 6.6 percent, the slowest pace of growth since 1990. Slowing growth in China does not augur well for key emerging economies, more deeply interlinked with the world’s second-largest economy and with each other than ever before (figure 4). And with the US economy also expected to suffer a slowdown between 2019 and 2020,11 growth in key emerging economies is likely to suffer. Even in India, where annual growth picked up in 2018 compared to the previous year, year-over-year growth in real GDP fell steadily from 8.1 percent in Q1 to 6.6 percent in Q4.

Oil-exporting emerging economies—such as Russia in Europe, and Nigeria and Angola in Africa—will face pressures if the recent spurt in oil prices, mostly due to supply cuts by key oil producers and fears of supply disruptions due to conflict in Libya and tightening sanctions on Iranian exports by the United States, fizzle out.12 Slower growth in China and a strong US dollar will likely keep other commodity prices also in check, thereby impacting growth in key commodity-exporting economies in Africa and Latin America. No wonder then that the International Monetary Fund (IMF) expects growth in emerging markets and developing economies to slow to a little under 4.4 percent this year from 4.5 percent in 2018 and 4.8 percent in 2017, with the agency cautioning about downside risks if stressed economies such as Argentina and Turkey do not recover as expected.13

Monetary policy dynamics will likely vary across economies

The global economic context is strikingly different in mid-2019 relative to just a year or two ago. Weakening global growth prospects and the Fed’s pause in monetary policy tightening have resulted in central banks in emerging markets either halting tightening cycles or reversing direction (figure 5). In fact, with inflation easing and economic activity slowing in emerging markets, a broad shift to monetary loosening could be in the cards. It is likely that economies will react differently. While most emerging economies are likely to shift focus to growth as economic activity slows, monetary policy in Argentina and, to a lesser extent, Turkey, will be geared more toward stabilizing their currencies and inflation outlook. In March, the Central Bank of Argentina hiked rates sharply once again, reversing the efforts between December 2018 and February 2019 to lower already-high interest rates. Add to this emerging market mix, upcoming elections in countries such as India and Indonesia. The mix of fiscal policies that results after the election of new governments in these economies may further influence the course of monetary policy there. A spoiler for oil-importing emerging economies could be a continuation of the recent rise in oil prices—between January 28 and April 22, the price of Brent has gone up by 23.8 percent. If this surge sustains, inflation in these economies may make a comeback, thereby dulling the likelihood of a shift in stance to monetary easing. For now, central bankers can only wait and pore over incoming data as they plot their next moves.

More from the Economics collection

-

Rising corporate debt: Should we worry? Article5 years ago

-

All in a day’s work—and sleep and play: How Americans spend their 24 hours Article6 years ago

-

How the financial crisis reshaped the world’s workforce Article5 years ago

-

A forecast of housing construction in the United States Article5 years ago

-

Millennials: The overqualified workforce Article5 years ago