The new frontier Winning in the African oil and gas industry

10 minute read

15 March 2019

Africa is the last energy frontier, a vast continent of opportunities and potential pitfalls. Eight factors should be considered by multinationals looking to invest and operate in Africa.

Africa is the last energy frontier, a vast continent whose oil and gas reserves are expected by some analysts to see it emerge as the new global hub.1 But Africa has a habit of dashing forecasts.

In 2000, The Economist dubbed Africa ‘hopeless’.2 Over the next decade, Africa rebutted that tag: labour productivity rose, inflation dropped and economies boomed. The Economist positively revised its opinion of Africa in 2011.3,4

Three years later, a crash in oil prices changed that upbeat narrative with a devastating economic blow to African oil-producing nations. Economies have slowly recovered and Africa’s gross domestic product (GDP) growth is expected to accelerate to 4 per cent in 2019,5 providing grounds for cautious optimism.

What remained unchanged throughout the period is the potential of the African oil and gas sector. The continent possesses 7.5 per cent and 7.1 per cent of global oil and gas reserves, respectively.6 As international energy prices recover, the continent is again attracting investor interest.

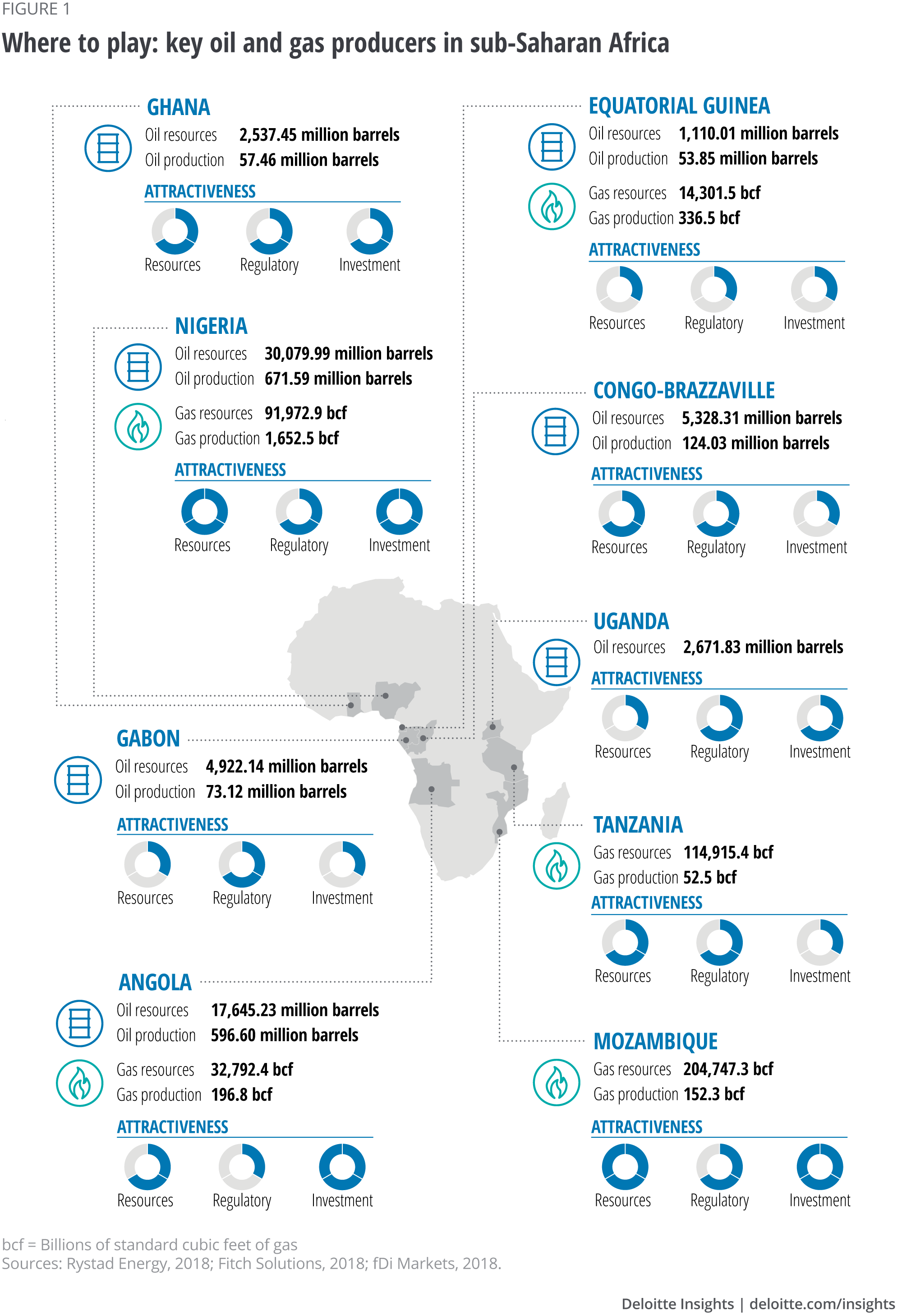

Recent oil and gas discoveries coupled with regulatory changes and fast-growing energy demand from expanding local consumer markets offer significant opportunities across the continent. In a 2018 report, African Oil and Gas State of Play, Deloitte examined notable destinations in nine sub-Saharan African countries.

In this article, we summarise the opportunities and potential pitfalls. It is not only the challenging operating environment, coupled with a lack of transparency, regulatory uncertainty and policy instability, and ongoing infrastructure deficit that hinder investment.

In African energy-exporting countries, oil and gas has historically been a primary driver of economic growth. Oil exports can account for more than 90 per cent of revenues and the bulk of fiscal revenues. Yet, countries have been unable to harness these windfalls for sustainable economic development and this is an ongoing constraint to business.

Players in the sector must also be mindful of disruptors likely to change the industry. These include rising global demand for liquefied natural gas; the growing prominence of renewables, which could have far-reaching implications; and the potential of the ongoing United States and China trade dispute to disrupt global trade, oil markets and supply chains.

Further, digitalisation is set to disrupt Africa’s oil and gas sector, where 30 per cent of production stems from legacy fields. The sub-Saharan Africa portfolio of ‘digitally behind’ assets risk becoming obsolete if digitalisation is not embraced. This makes the sector ripe for disruption, presenting opportunities for producers and other industry players.

How the African industry is evolving

Nigeria is a mature oil-producing economy with substantial foreign direct investment (FDI), but delays in reforming the sector have deterred further investment. Governance challenges, corruption, as well as economic, security and high cost concerns also hinder investment.

The country is still the region’s largest oil and gas producer overall and is expected to be the largest refiner and exporter of petroleum products in Africa by 2022. Improving economic conditions and transport sector growth could see domestic consumption increase by 31 per cent between 2017 and 2023. Investment in gas infrastructure, such as new pipelines, will boost production. Opportunities exist for players with the government intending to privatize ten power stations as part of efforts to guarantee an effective and sustainable power supply in the country.7

Angola is less attractive from a regulatory perspective. It also grapples with corruption, high business costs, low growth and a lack of business diversification. Yet, Angola has the second-largest oil resources and is the second-largest oil producer in sub-Saharan Africa.

As a result, it is receiving increasing levels of FDI, boosted by the Angolan government passing several policies in early 2018 encouraging foreign investment.

Angola also has the fourth-largest proven natural gas reserves, although the country only produces small amounts commercially. A 2018 presidential decree offers incentives for investment. Consumption is expected to more than double between 2017 and 2023, although the large distances between gas production sites and consumers and a lack of pipeline infrastructure are significant constraints.

Several African countries are looking to stimulate investor interest through affiliation with the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC).

Congo-Brazzaville joined OPEC in 2018. This, together with a licensing round of 18 blocks (onshore and offshore), could increase investment and reverse declining reserves and production. Production will ramp up in 2019 as projects come online. Refined products consumption has been rising, growing by 28 per cent between 2010 and 2017. This should continue to grow apace with the country’s rapidly increasing population. Refinery capacity is still the main constraint.

Equatorial Guinea joined OPEC in 2017, but lacks new discoveries and is working maturing oil fields. While oil and gas resources are likely to shrink in the coming decade, the country is still the second-largest producer of natural gas. In May 2018, Equatorial Guinea announced plans to develop a natural gas mega hub linking onshore processing and offshore production facilities.

Crude production has been on the decline in Gabon since 2010. The country re-joined OPEC in 2016 and revamped legislation in the hope of attracting investment, particularly for offshore exploration. These revisions should make licensing and fiscal terms more competitive and flexible.

New contenders

While established oil and gas countries look to reinvigorate FDI, the spotlight is also shining on Africa’s new contenders. As the region’s newest oil producer, Ghana has seen the highest growth in oil production among its peers.

In late 2018, the country launched its first offshore licensing round with six blocks. This contributed to a rise in exploration activity. A long-debated Petroleum Bill, passed in August 2016, is set to improve the broader regulatory environment and remove major barriers to exploration.

A favourable ruling in September 2017 on the long-running maritime border dispute with Côte d’Ivoire also brightens the country’s prospects. But refining capacity is constrained, and limited oil pipeline infrastructure may affect consumption.

Mozambique holds the largest gas resources in the region, so has the largest untapped potential. Domestic and governance challenges aside, the country has seen the largest flow of FDI over the past eight years among its peers.

Recent discoveries multiplied proven reserves and will underpin the country’s projected economic recovery. Plans for the coral floating liquefied natural gas development in the Rovuma Basin, as well as the Anadarko Petroleum project in the north are two prominent developments. Given the complexities of these projects, production is not expected until 2022.

Tanzania has the fastest-growing economy among its oil and gas-producing peers in the region and the second-largest natural gas resources. While production is low, the discovery of new offshore fields has the potential to transform the economy. Its closer location to Asian markets gives Tanzania a geographical edge over peers, although exports of liquefied natural gas based on a planned onshore export facility have been delayed for at least five years.

Another market to watch is Uganda. Discoveries in 2006 proved the country has the fifth-largest oil resources in the region and new exploration licences are being awarded. Production is expected to start in 2021 and the construction of a pipeline from Hoima (Uganda) to Tanga (Tanzania) began in 2018.

Considerations for winning

There is no universal recipe for winning in the sub-Saharan Africa oil and gas sector. However, soft and hard skills, paired with the right timing, and an understanding of market-specific conditions will bring success. Eight factors should be considered by multinationals looking to invest and operate in Africa.

Investing in local partnerships. Given the complexity and nuances of local markets, finding the right local partners is crucial. Partnerships may range from those focused on geographical and technical expertise to those that provide access to networks, channels and local decision-makers.

Local partners with on-the-ground experience can help entrants understand local business etiquette and culture. These ‘softer’ elements are crucial to success. Partnering with experienced businesses can help a market entrant navigate the local regulatory environment, overcome distribution challenges and avoid costly mistakes.

The complexity of the search for the right partner should not be underestimated. Due diligence is necessary when evaluating potential partnerships, particularly in the context of mitigating the risk of unwittingly becoming complicit in corruption.

Capitalising on local market knowledge. Working with entities across the public and private sector can prove difficult given the trust deficit between governments and businesses. To narrow this, use trusted local advisors and mediators with a proven track record. While hiring local staff is one choice, partnering, or acquiring local firms allows fast-track access to knowledge and networks.

Although a wealth of data, information and insights exist on African economies, investing in data collection, on-the-ground insights and expert information is also crucial. In-country market experience allows companies to gain first-hand knowledge and to build long-term strategies.

Understanding local customs and business culture. Investing in partnerships and market knowledge promotes an understanding of local customs and the business culture. Players need to consider their ‘style’ of entering a new market. Business practices differ and the wrong approach might come across as overconfident or arrogant. Intelligent engagements with stakeholders can help ease market entry.

Building a winning business in Africa is a longterm play. A focused approach to understanding the practices and customs in one market may help expansion into other African economies.

Developing local content and localisation strategies. Players must embrace localization to lower supply chain costs, boost local skills development, reduce risk and enhance their reputations with the governments and local communities in which they operate.

Local legislation prescribes or at least encourages a minimum procurement of local goods, services and labour. The consequences of noncompliance vary from monetary penalties to impacts on the granting or renewal of licences. For local content to be sustainable, a long-term and end-to-end localisation approach must be followed throughout the project life cycle from exploration through to decommissioning.

To develop longer-term and broader-view localization strategies, players should engage with local communities, authorities and stakeholders from early on. The value of localisation plans appears when they form part of the overall development plans of the host country. It is then that localisation strategies create true socioeconomic value.

Creating value beyond compliance. When navigating the compliance landscape, companies must move beyond ‘tick-the-box’. Implementing industry and technical expertise helps companies enable increased socioeconomic impacts, improve business and operational efficiencies, and share value.

Creating value for surrounding communities and contributing in a meaningful way to economic diversification and developmental challenges needs a new socioeconomic framework and new business models. The principle of Shared Value is such a framework. It aims to address social issues with a business (profit) model to make positive gain and win-win choices where stakeholders (players, communities and local government) share an interdependent future. The key premise is that the competitiveness of a business and the health of the community in which it exists are interwoven.

Through business decisions, policies and practices related to products, services, supplier, and local economic cluster development, companies can advance the economic benefits and social conditions of their communities while enhancing their competitiveness. Active stakeholder engagement and communication are required on a long-term basis to fulfil potential and manage risks.

Portfolio management and diversification. Players need to decide on their portfolio at the outset of operations. Diversification beyond core business functions may be necessary to overcome business challenges omnipresent in many African countries. For example, ensuring electricity for day-to-day business operations may mean investing in power infrastructure.

Acquisitions for securing infrastructure, skills, or distribution networks is one approach. Strategic acquisitions enable firms to diversify their portfolio and move into new sectors. For example, some firms have looked to balance the risk of commodity price fluctuations in oil and gas by diversifying into renewable energies.

As capital intensity, cyclical prices, and long horizons rule oil and gas operations, portfolio management focusing on the core business is important. As portfolios evolve, they need to be rebalanced for greater focus on transformational changes that leverage multiple types of innovations simultaneously.

Embracing digitalisation. Robotics, digitisation, and the Internet of Things (IoT) are transforming the operational environment of oil and gas companies, creating greater productivity, safer operations, and cost savings. However, a Deloitte survey of industry executives found current initiatives focus on core innovation with shorter term returns. This approach is linked to the challenges faced in re-evaluating projects following the oil price downturn after 2014.8

For players, one of the advantages of adopting digital technology could be the resilience these technologies offer to downturns and adverse consequences in Africa. Players benefit from a coherent framework that helps achieve near-term business objectives, measures digital progression through stages of evolution, and offers a pathway to transforming the core of operations, real assets and the business model. A strategic road map can assess the digital standing of every operation and identify digital leaps for achieving specific business objectives.

Further, the rapidly changing dynamics of the industry require new technology-driven solutions to respond to disruption. Disruptors stem from many avenues, including customers expecting a consistent digital experience across channels and content.

Identifying risks and planning for uncertainty. Companies need to plan for the risks of investing and operating in Africa. These include regulation and policy, third parties such as partners or suppliers, infrastructure, labour and the environment. Macro risks, such as political, security, governance, economic, structural, country liquidity and currency risks, also loom large. Technological risks, such as cyber and other digital risks are also becoming more prominent in Africa.

Political tensions are often short-term, and associated with elections and fast changing perceptions. These can receive broad media coverage and firms need to respond quickly. Long-term risks, like structural issues within a society, come with less urgency and mitigation is long and costly. Yet, these often prove to be most damaging. To help navigate the complexities and to chart a path of success, tools such as scenario planning help identify and mitigate risks in innovative ways.9

In practical application, there is no one-size-fits-all approach. Risk, compliance and controls need to be integrated in one system across the firm. Further, players need to make sense of the local environment and develop local mitigation strategies for individual markets, rather than at a group level. Understanding the evolving risk landscape enables risks and opportunities to be managed in a way that is both opportunistic and sustainable.

Conclusion

The conclusions presented in the article are based solely on assessment of the oil and gas sectors in the individual countries and do not refer to the broader socioeconomics aspects of particular countries.

It is important to note that the eight cross-cutting factors outlined cannot occur in isolation. A key ingredient is to establish an ecosystem that enhances collaboration between various industry stakeholders. Such ecosystems are fostered by incentives that encourage organisations to participate, thereby unlocking further collaboration and innovation.

Ultimately, ecosystems lower costs and encourage innovation through collaboration between players along the supply chain. Trust between suppliers and operators is vital to create long-term partnerships that can reap the benefits of an integrated environment. Nurturing an ecosystem where innovation can truly thrive is essential in the African oil and gas industry to generate significant value for customers, shareholders and employees.

© 2021. See Terms of Use for more information.

Read more on Oil and Gas

-

The new frontier Article6 years ago

-

How the shale revolution is reshaping the US oil and gas labor landscape Article6 years ago

-

Global renewable energy trends Article6 years ago

-

Building a fit-for-the-future portfolio in upstream oil and gas Article6 years ago

-

From bytes to barrels Article7 years ago

-

Your mileage may vary Article8 years ago