Brazil: New president, old economic challenges

4 minute read

20 December 2018

President-elect Bolsonaro has his work cut out. Brazil's economic recovery has been slow and fiscal worries abound. While he appears to be making the right economic noises, any slack in implementation may just turn the tide.

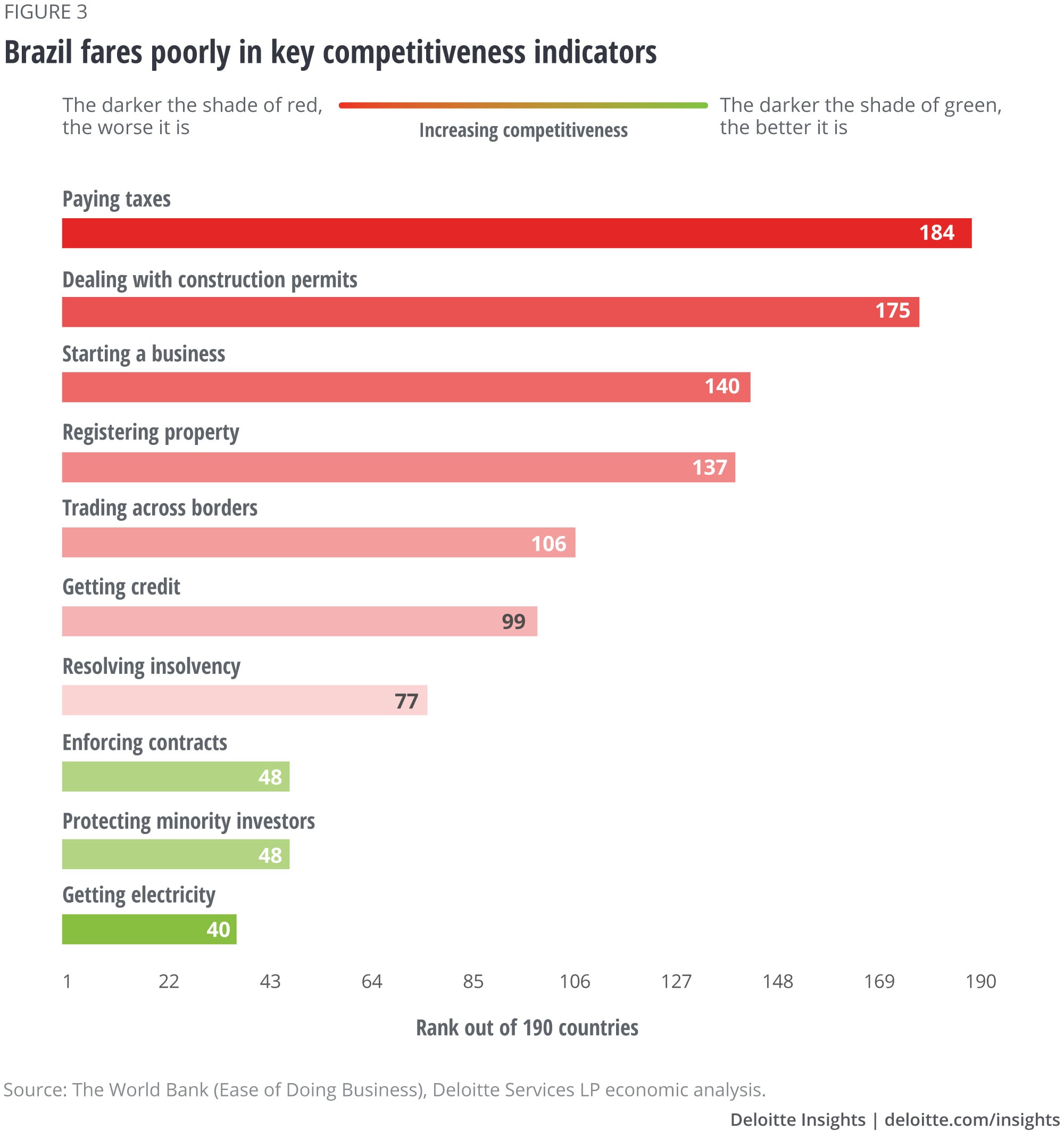

On January 1, 2019, Jair Bolsonaro will take over as the 38th president of Brazil.1 While no election in a modern democracy is a cakewalk, Bolsonaro’s economic challenges are more daunting than his presidential quest. The scars of the downturn of 2015–2016, the most severe since the new national accounts series started in 1990, are deep even as the recovery is slow.2 Real GDP in the second quarter was still 6.0 percent below what it was in Q1 2014. Yet it’s not just near-term economic activity that Bolsonaro will have to focus on. Fiscal health is a major worry—the country lost its investment-grade rating in 20153—and efforts so far to reform public expenditure have not been comprehensive.4 The economy also faces a lack of competitiveness; its tax regime, for example, is crying out for change—Brazil ranks 184 out of 190 countries in the World Bank’s doing business rankings on paying taxes.5 The president has started on the right note, cobbling together a credible economic team that has been lauded by financial markets.6 That is perhaps the easy part. Getting key legislation through to reform different sections of the economy will likely be more difficult.

The economy is clawing its way back, but only just

Learn more

Explore the entire Economics: Americas collection

Subscribe to receive more economics content

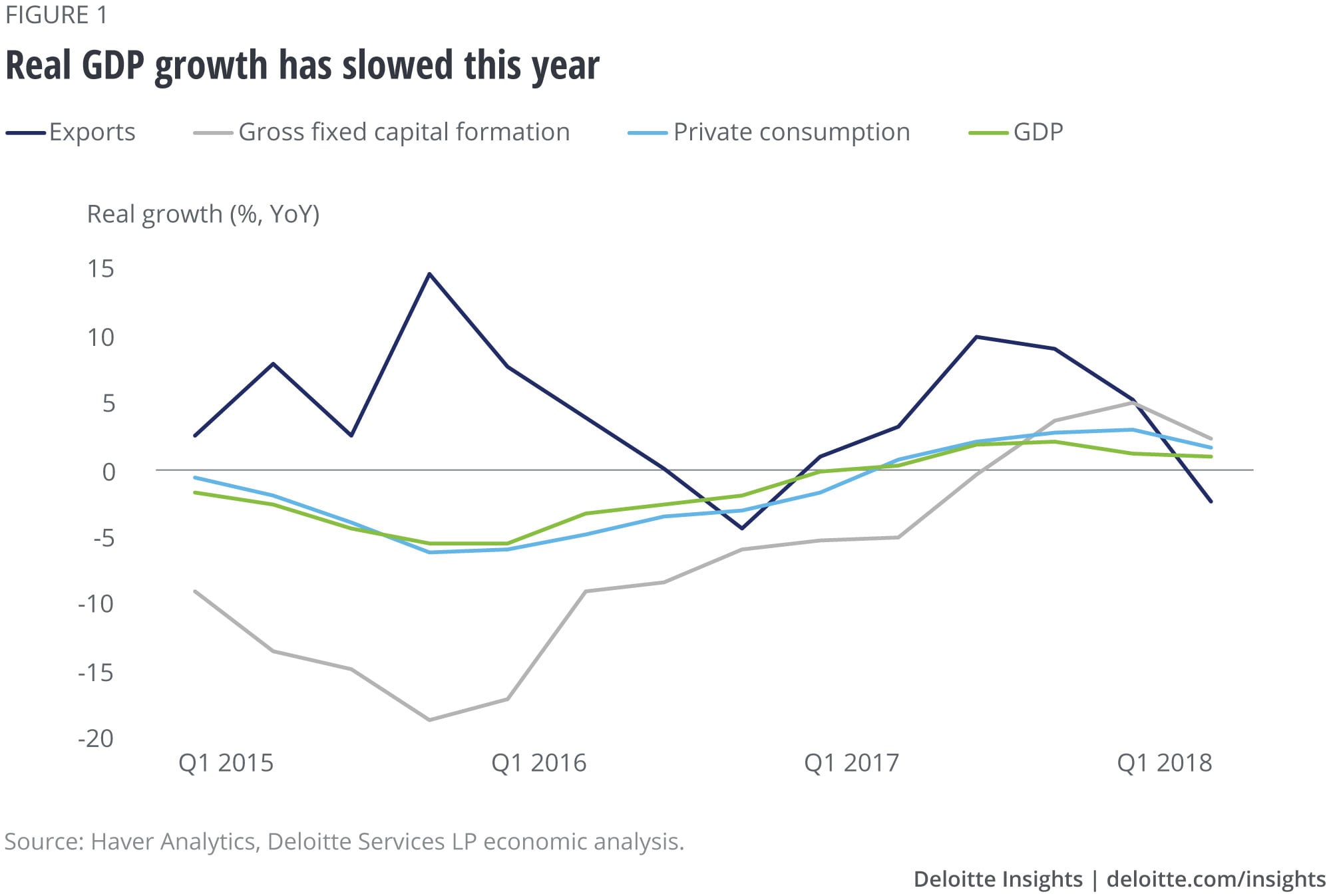

The economy expanded by 1.0 percent year over year in Q2 2018, slowing marginally from the 1.2 percent rise in Q1. Indeed, Brazil’s economic recovery has been slow due to poor fiscal health, elevated debt and debt-servicing costs for consumers and businesses, and a lack of strong progress in improving long-term private sector competitiveness.7 Contribution to economic growth by consumers and businesses has slowed this year. Private consumption growth, for example, slowed to 1.7 percent in Q2 from 2.9 percent in Q1. Exports too suffered a setback in Q2 (figure 1) and government spending is unlikely to contribute directly to growth in the near to medium term as policymakers try to curb high public debt. Given this scenario, it is not expected to be a V-shaped economic recovery.

What’s holding back consumers?

For consumers, labor market gains have been low given the slow pace of the current economic recovery. The unemployment rate (three-month moving average) was 11.9 percent in September, lower than the high of 13.7 percent in March 2017, but a long way to go to reach the December 2013 low of 6.2 percent. Net job gains, on average, have turned positive only this year (January to September) after suffering average annual declines since 2015. These numbers indicate that there is still much slack in the labor market. No wonder then that real wage gains have been low—real average earnings have grown by just 1.0 percent so far this year, down from 2.3 percent in 2017; the figure, however, is better than the 2.3 percent decline in 2016.

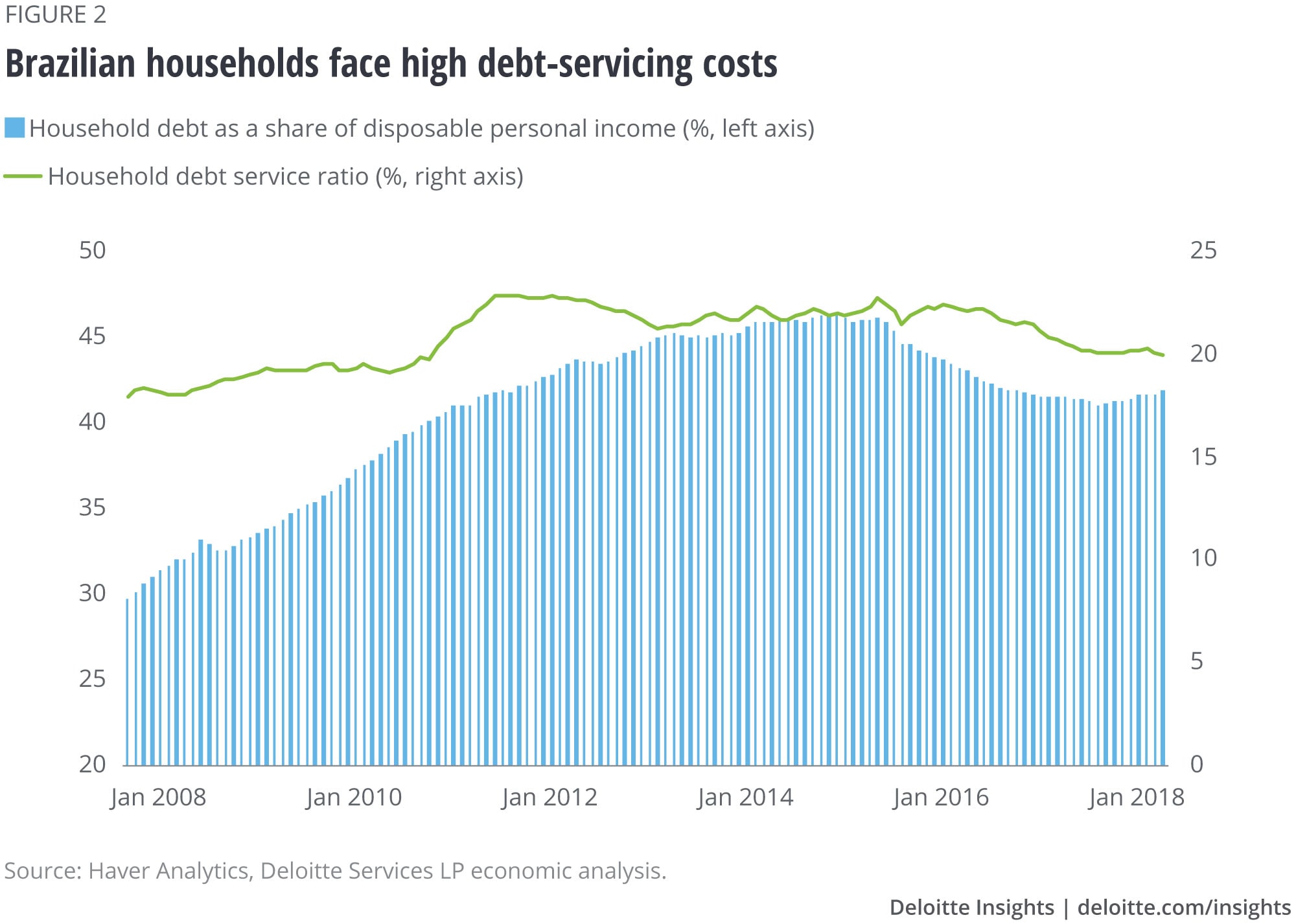

Households are also struggling with high debt and debt-servicing cost. Back in January 2005, when an economic boom was underway, household debt was 18.4 percent of disposable personal income, but by September 2018, it had risen to 41.9 percent. While this may seem low relative to the figures for Canada, Australia, and some Southeast Asian nations, Brazilians face challenges in servicing and drawing down debt.8 First, income growth has slowed in recent years: Personal disposable income grew 4.7 percent per year, on average, in 2014–2017 compared to 11.6 percent in 2010–2013. Second, the debt-servicing cost is high (figure 2) due to high lending rates. For example, even though the target interest rate in September was 6.5 percent, the average lending rate was 38.1 percent.9

Businesses grappling with twin problems of demand and competitiveness

Like consumers, businesses are also facing a challenge with high lending rates. High rates, along with weak demand growth, are likely to weigh on business investment in the coming quarters. Retail sales volumes, for example, have grown by just 2.2 percent so far this year, a far cry from the 8.4 percent rise back in 2012. In the face of slowing demand, businesses have been loath to invest. And that too when they have existing capacity to fall back on should demand rise quickly—capacity utilization in the industry was 77.8 percent in September, much lower than in the pre-downturn years (82.2 percent in 2012 and 82.5 percent in 2013). It’s interesting to note that real gross fixed capital formation grew for the first time in 15 quarters in Q4 2017, an indication of how much businesses have suffered in recent years.

Demand may not be enough to induce strong business investment over the medium to long term; for that, the economy’s competitiveness has to improve (figure 3). According to the World Bank’s 2019 rankings for ease of doing business, Brazil ranks 109 out of 190 countries, much below emerging market peers such as China (46) and India (77).10 The current rank is despite the recent easing of cross-border trading, reforms in credit information, and introduction of an online registration system for companies.11 It still takes 1,958 hours in a year in Brazil to pay taxes; contrast this to Singapore’s 49 hours.12 This dents tax payments and collection, especially from small businesses who may not be able to afford the large talent pool of accountants and finance professionals to pay taxes.

Time to walk the talk

To tackle short-term demand challenges as well as to initiate long-term reforms will be a big ask for the new administration. Coalition building to pass contentious reforms won’t be easy given the plethora of parties in the new legislature—there are 30 parties in the lower house.13 A good start perhaps would have been to pressure the outgoing legislature to pass minimal pension reforms before the new one takes over—with elections over, previous legislators would have less to worry of repercussions at the ballot box than the newly elected ones. But that seems unlikely now.14 Nevertheless, the president-elect and his team have made the right economic noise so far.15 The decision to merge certain ministries to cut the flab and the appointment of reputed people to key posts (like Paulo Guedes to the consolidated economy ministry) have reassured financial markets—between October 29 and November 27, the Ibovespa has gained 4.9 percent.16 Yet as often witnessed, markets are unforgiving as well. Any slack in tackling key challenges may just turn the tide. That is something that the president-elect would like to avoid.

© 2021. See Terms of Use for more information.

Explore more economics content

-

Canada Economic Outlook Article4 years ago

-

Global Weekly Economic Update Article4 days ago

-

Trade in services: Vital to US economic growth Article8 years ago

-

Consumer spending: Understanding what it is and how it is evolving Article6 years ago

-

All in a day’s work—and sleep and play: How Americans spend their 24 hours Article6 years ago

-

Mexico economic outlook, January 2025 Article2 months ago