Consumers in advanced economies A tussle between tailwinds and headwinds

09 November 2018

Consumer spending in advanced economies seems to be on the upswing, buoyed by healthy economic activity and improved labor markets. However, rising tariffs and slow real-wage growth could play spoilsport.

Consumers in advanced economies appear to be back with a bang. In the United States, personal consumption expenditure grew 4.0 percent (at a seasonally adjusted annual rate) in Q3 2018, continuing the momentum of the past few years.1 In the Eurozone, consumers are slowly clawing their way back from the worst of the sovereign debt crisis of 2011–2013, with spending growing steadily since Q4 2013 (figure 1). Even in Japan, where the specter of deflation is yet to be completely routed, the role of consumer spending in GDP growth picked up in 2017 and in Q2 2018.

Learn More

Subscribe to receive more economics content

What explains this surge in consumer spending? More importantly, will the good times continue? It is likely that healthy economic activity, improving labor markets, and rising sentiment have all come together to prop up consumer spending in recent times. There are, however, clouds that lurk on the horizon—from rising tariffs to slow real-wage growth. And whether they will prevail over tailwinds is a question that many will likely be asking.

A swathe of factors is supporting consumer spending

Strength in consumer spending should come as no surprise, given steady economic growth and improving labor markets. In the United States, private sector nonfarm payrolls have grown by 200,000 per month this year until September, while unemployment fell to a 49-year low of 3.7 percent. In Europe, unemployment in the United Kingdom is at its lowest since February 1975, while in Germany, it is at the lowest since unification. Even economies that bore the brunt of the sovereign debt crisis are witnessing a labor market recovery, although slack remains in some. In Spain, unemployment was 15.2 percent in August, much below the peak of 26.3 percent in 2013, but still above the pre-2008 trough of 7.9 percent. And even in Greece where real GDP is still 25 percent below its 2017 peak, unemployment has been edging lower.

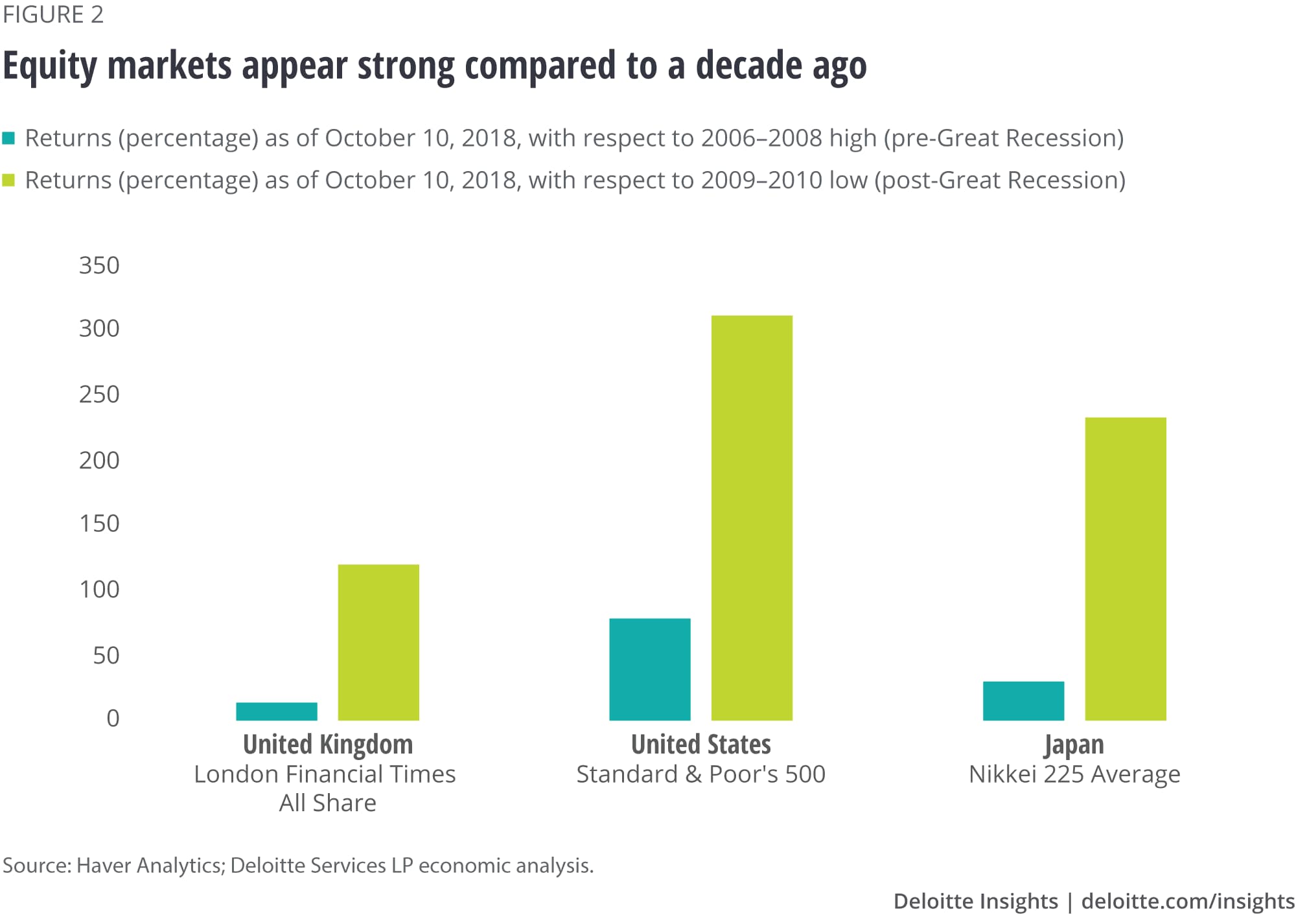

Consumers are also benefitting from rising income. Growth (year over year) in disposable personal income in the United States has averaged about 5.0 percent per month so far this year—thanks to tax cuts2—up from 4.4 percent in 2017. In the United Kingdom, however, household disposable income growth has been more muted since a strong annual rise in 2015 (5.7 percent). Adding to the surge in income are gains in equities and housing, both key components of household wealth. Despite recent volatility, equities have gained much in the United States, Europe, and Japan from a decade ago (figure 2). In the United States and the United Kingdom, home prices are now higher than their pre-crisis peaks. And even in Australia, despite slight declines this year, residential property prices are still up 61.8 percent compared to a decade ago.

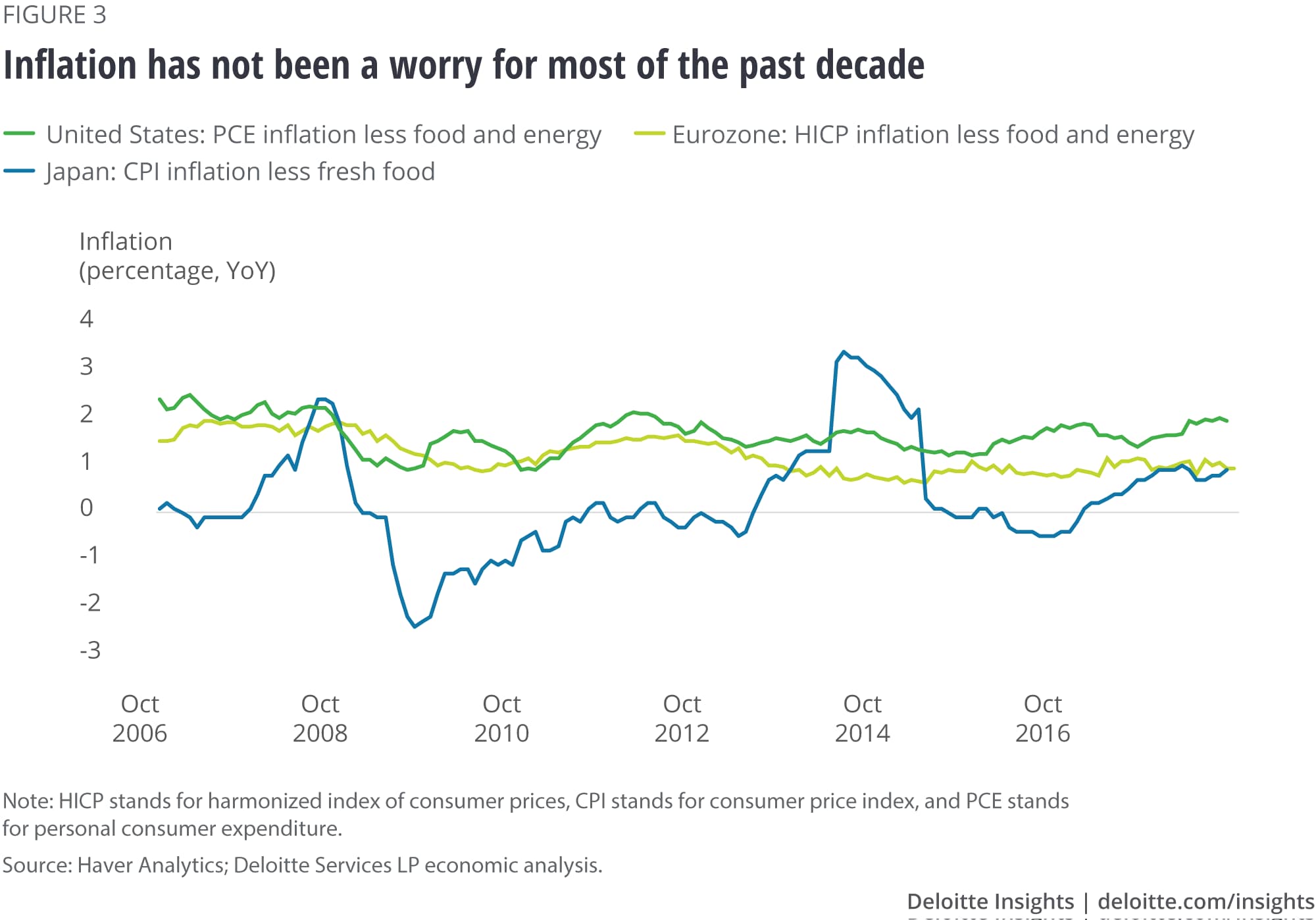

Consumers have also benefitted from nearly a decade of low interest rates. The US Federal Reserve (Fed) started raising rates only in late 2015 and the pace of increase has been gradual.3 The European Central Bank (ECB) has until now not changed its ultra-low policy rate regime, although it has toned down its asset purchases program.4 And Japan shows no signs of changing its loose monetary stance any time soon.5 In such a scenario, consumers have benefitted from lower costs of borrowing. With inflation still within respective central banks’ range (figure 3), purchasing power has received a boost for much of the past decade.

Clouds on the horizon

The current bout of consumer strength is, however, not immune to headwinds. Some of these are headwinds arising from policy changes such as rising tariffs, while others such as the rising burden of housing costs and rent are more to do with asset price trends. While some of these may be more near-to-medium term in nature, others, such as an aging population and its impact on dependency, have more long-term implications.

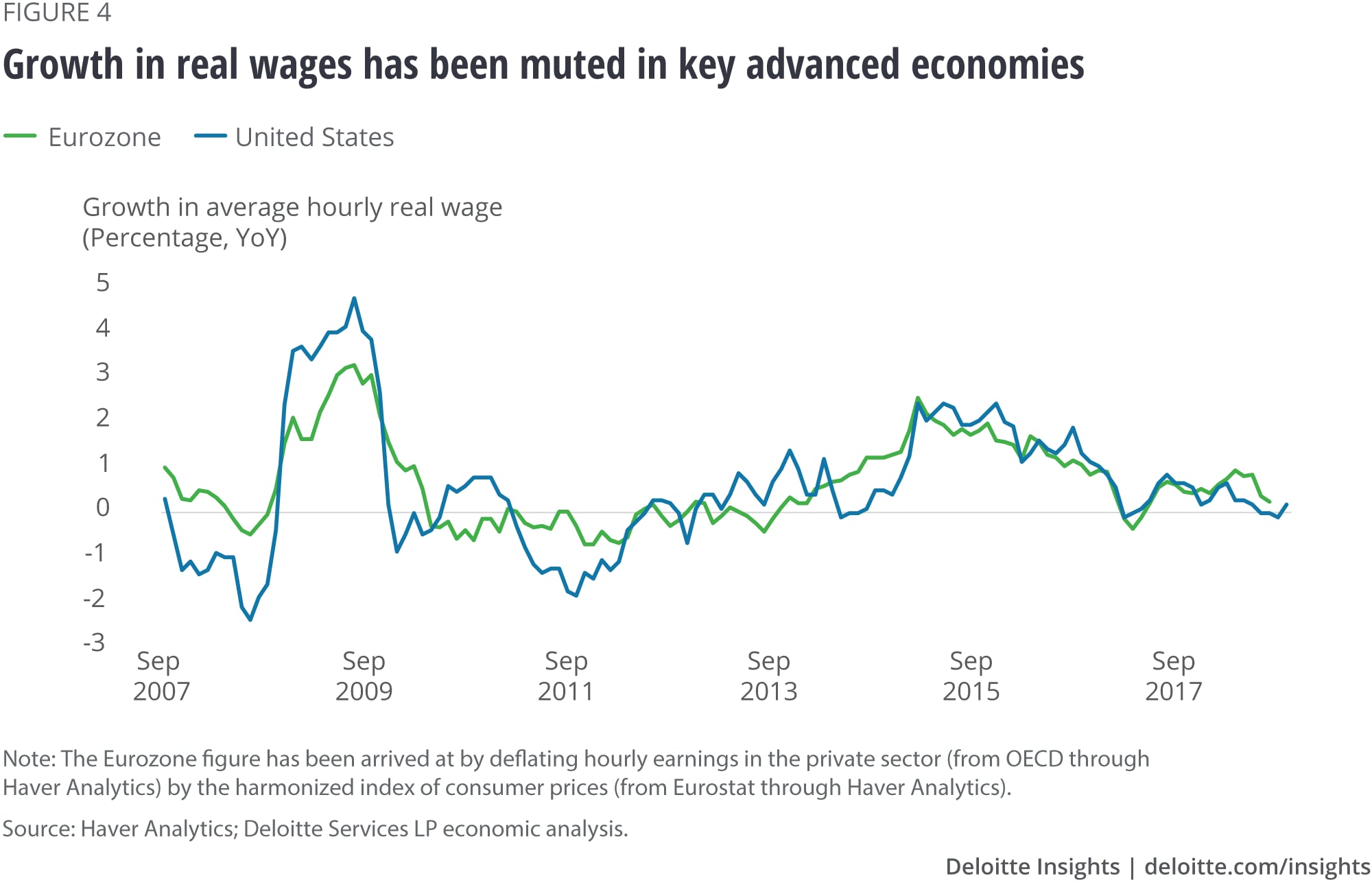

That slow real-wage train

While incomes have been rising, real wages—nominal wage adjusted for inflation—have not gone up by much, thereby weighing on consumers’ purchasing power. In the United States, the average annual growth in real average hourly wage has gone from 2.2 percent in 2015 to just 0.4 percent in 2017; real wages have gone up by less than 0.2 percent so far this year. Surprisingly, this slow trend in real-wage growth is despite a tightening labor market. The story in the eurozone is no different—wage growth in recent years has been muted at best (figure 4). The worry is that if wages don’t pick up fast, any rise in inflation could further derail real wages.

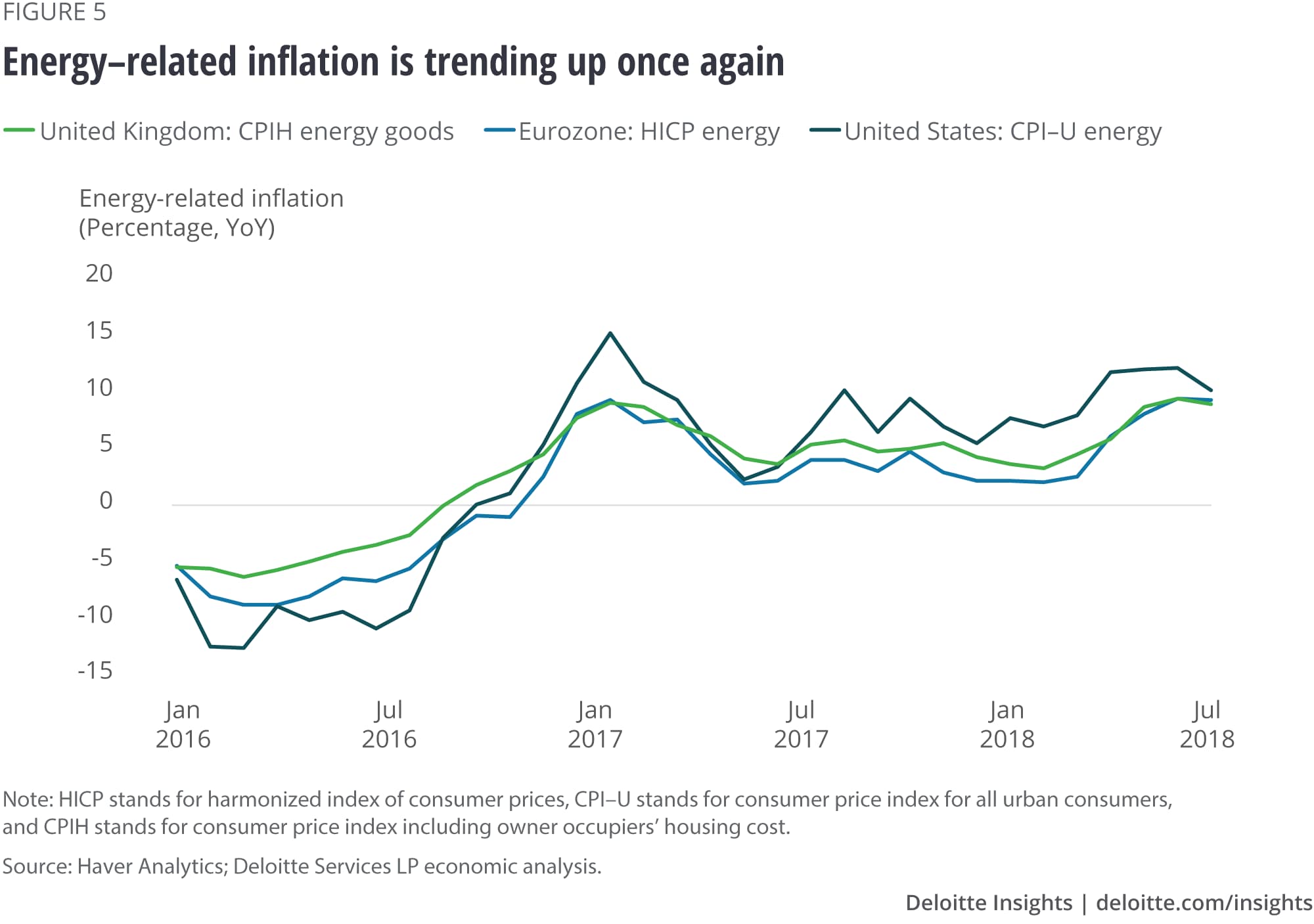

The fumes of rising fuel prices

The elongated spell of low-to-moderate inflation in advanced economies could change. First, rising energy prices will likely dent consumer wallets. Global oil prices, subdued for much of 2015, have since picked up pace. Brent, as of October 10, is at US$ 83.0 per barrel, up 24.5 percent this year following rises of 17.4 percent in 2017 and 49.2 percent in 2016. With the agreement between OPEC and non-OPEC members to cut output holding for now6 and Iranian supplies likely to be hit beginning in November due to US sanctions,7 oil prices will likely remain elevated in the near term. Rising hydrocarbon prices have, in turn, pushed up the energy component of consumer inflation (figure 5). Second, as the trade tiff between the United States and China intensifies,8 the casualty may be consumer budgets as import prices rise; any supply chain disruptions of major US and European manufacturers in Asia and North America will likely add to the pain.9 Finally, aggregate demand itself is rising fast in countries such as the United States, and this will likely put more upward pressure on inflation.10

Of rising housing costs and worries of bubbles in some economies

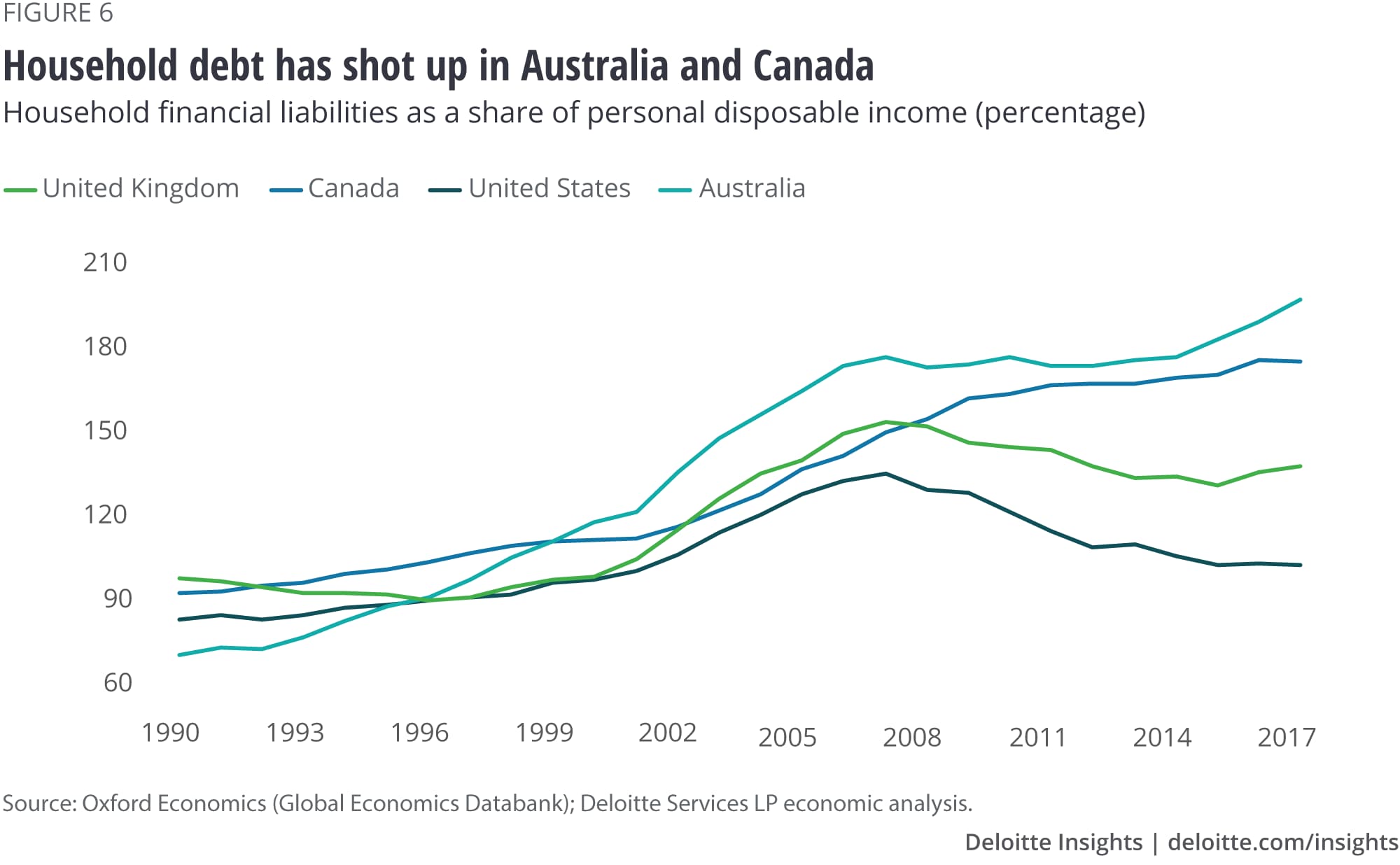

As home prices and interest rates rise in the United States, the American dream to own a home is still a bit more distant for some despite the recovery post the Great Recession.11 The homeownership rate (64.4 percent in Q2 2018) is still below the peak of 69.4 percent in Q2 2004, and consequently, people are renting more.12 This has boosted rents—rent-related inflation has been rising faster than headline inflation since May 2012,13 thereby denting consumer purchasing power. In some of the world’s biggest cities—Hong Kong, San Francisco, New York, London, and Toronto—soaring prices are making homes unaffordable for even high-skilled workers;14 the alternative to buying—to rent—is denting people’s finances as rents rise with more demand.15 Those who don’t own a home (or equities) have been left out of the surge in home prices (or equities) over the past decade and are hence losing out on the consequent rise in wealth.16 Rising home prices also likely raises the risks from high household debt, a key factor leading up to the Great Recession. This is worryingly evident in Australia and Canada, although US households appear to have moved away from the high debt levels of 2007–2008 (figure 6).17

Taking on the burden of aging

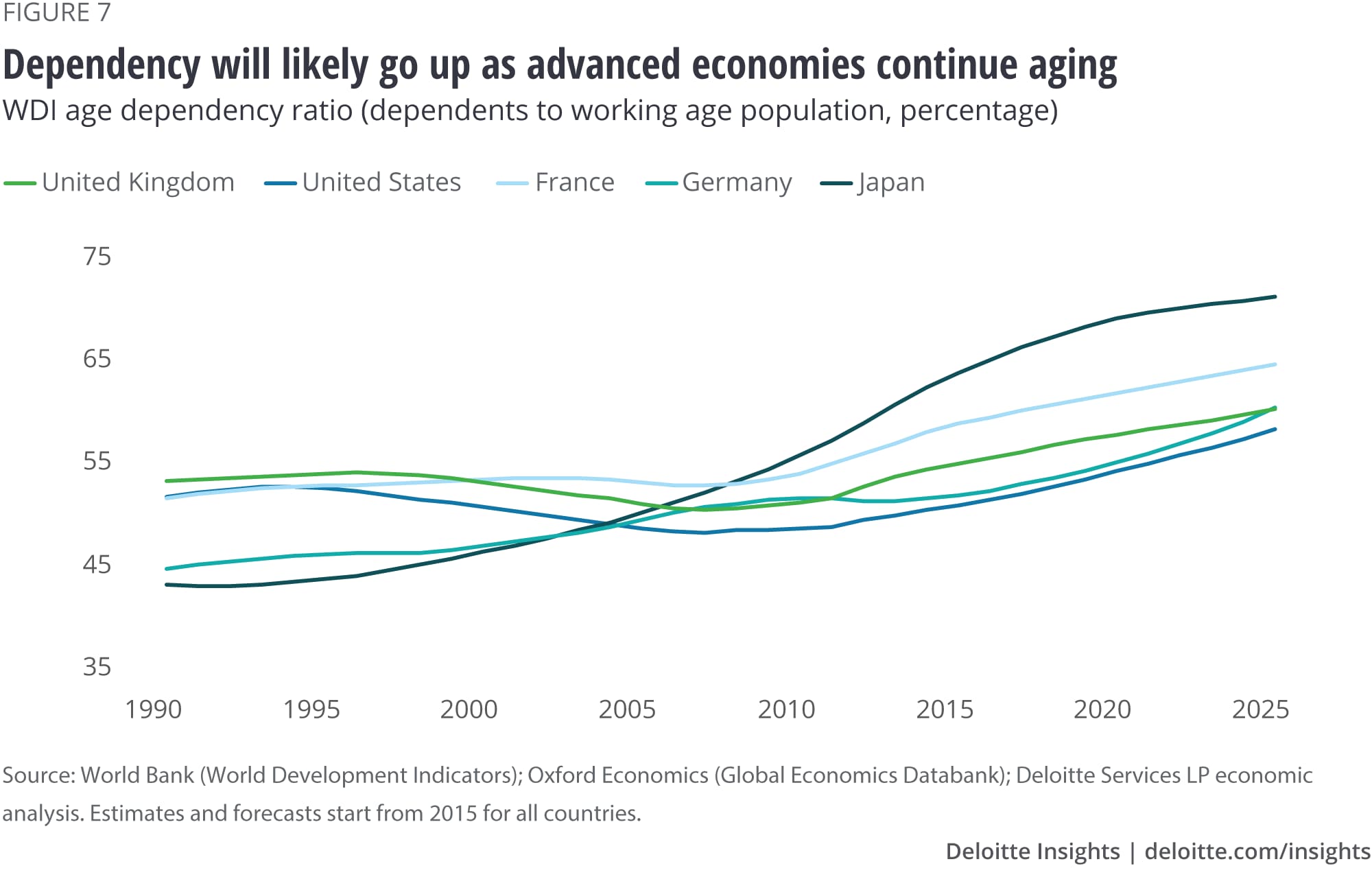

The population in advanced economies are aging and with it the burden of supporting the elderly is increasing.18 This is perhaps most evident in Japan where those aged 65 years or above are likely to constitute 29.3 percent of the population by 2025, up from 11.9 percent in 1990; in contrast, the share of those aged 14 years or below is expected to fall to 12.4 percent from 18.4 percent during this period.19 With this trend likely to continue in Japan and many key advanced economies, the burden of supporting an elderly population will increase (figure 7).20 And this won’t be easy given the lack of strong productivity growth in the past decade.21 In such an environment, younger households today can either expect to pay more taxes in the future (or save more) and spend less while staring at a longer retirement age.

Treading with a bit of caution

Will the tailwinds supporting consumer demand be able to outsmart the risks in the horizon? It’s not clear now, although consumers will likely not have a smooth ride. With borrowing costs set to rise as the Fed keeps to its gradual rate hike path and the ECB winds down its assets purchase program, consumers’ ability for home and even some retail purchases will likely be affected, especially if real wages remain sluggish. And even if consumer spending crosses all these hurdles, both the quantum and pattern of consumption may change in the future in advanced economies due to factors such as aging, and rising income and wealth inequality. Income inequality has been going up fast in key advanced economies with wealth inequality apparently even starker than income inequality.22 And a study by Deloitte found that there is also a widening wealth chasm between younger households and older counterparts in the United States, thereby setting the stage for a poorer country in the future.23 This may well lead to subdued spending by younger households, especially those down the income and wealth ladder.

© 2021. See Terms of Use for more information.