Breaking the mold: The future of Indian educators Insights from 2019 Deloitte Deans’ Summit

9 minute read

20 August 2019

The workplace increasingly requires a multiskilled workforce. The Indian education system needs to transform itself, beginning with the reskilling and upskilling of educators to meet the requirements of tomorrow’s workforce.

When dean Danish—“Dan” to his students—started his career as an academician, he was not too familiar with the inherent issues in Indian higher education. But, as a faculty member, he gained insights about them over the years. Lately, these issues have begun to percolate into his own institution. He is particularly worried about the dearth of quality faculty. Dan’s institution has long been aware of this “shortage,” but had taken only ad hoc measures, such as hiring temporary professors, to manage the situation.

Learn more

Explore the Future of higher education in India collection

Download the Deloitte Insights and Dow Jones app

Subscribe to receive related content

Dan also believes that the rate of technological transformation makes it imperative not only for the future generation of employees (today’s students) to be adept at using technology but for faculty as well to be able to teach students using education technology (EdTech), such as mixed reality capabilities (encompassing virtual and augmented reality). According to him, the future will require teachers to break the current mold and reimagine their skills—the literal and the subtle, the obvious and the nuanced—in the context of changing realities.

Dan is not alone in worrying about these issues. In fact, in our recent survey of deans (see the sidebar “Understanding the Indian higher education sector” for more information on our methodology), more than eight in 10 deans (heads of educational institutions like directors or principals) worry about the lack of quality faculty in the Indian higher education system.1 They also understand that the roles and responsibilities of educators (faculty members, deans, and directors) are becoming centered around how they can play an integral part in enabling the future of work and the workforce—expanding beyond their current boundaries.

Understanding the Indian higher education sector

In April 2019, Deloitte conducted the Deans Summit for deans, directors, principals (all will be referred to as deans in this article) of 63 top-tier institutes in India. The deans from various institutions—including business, engineering, and other undergraduate schools—deep-dived into the challenges faced by the higher education sector and discussed ways to address them. In addition to the deans’ roundtable discussion, Deloitte surveyed the 63 deans, more than 900 alumni, and over 3,000 current students from these institutions. The insights gathered from a solutions lab and the survey have been captured in a series of four articles covering the following topics:

- Future of higher education

- Future skills of educators

- Future of work

- Reengaging alumni

This article focuses on the “Future skills of educators” and is a culmination of research, conversations with the deans, and a survey of different stakeholders in the Indian higher education market.

What new skills might the “Indian higher educator of tomorrow” require to be successful in a competitive marketplace? What’s triggering this need to upskill and reskill the Indian educator? How can deans play a more inclusive and holistic part in driving this change? How can EdTech help solve the problem of faculty shortage?

Drivers behind the skills revamp of Indian educators

Students will be entering a workforce where disruption and uncertainty are the norm and a multiskilled workforce is the top priority. Educators therefore need to revamp their own skills to adequately equip the future workforce. Primarily, three forces are driving this transformation:

- Students look for an “education experience”: The current set of students is veering toward science-based disciplines,2 and they are looking for an experiential learning-based education. In a recent Deloitte survey, 64 percent of students expressed this preference.

- The future workforce needs to be multidisciplinary: Convergence of multiple disciplines will play an important role in solving the world’s most challenging problems, and today’s students need to be equipped with more than one skill. The use of technology has now redesigned jobs into super jobs that also require more human skills such as problem-solving, communication, interpretation, and design.3 Faculty will therefore need to be well-versed and equipped in such disciplines and skills.

- An acute skills gap resulting from rapid advances in technology calls for a curriculum overhaul: Employers are finding it difficult to find job-ready professionals. For example, 48 percent of Indian employers report difficulties filling job vacancies due to talent shortages.4 One reason is that barring a few top institutions, Indian curricula are yet to catch up with the rapidly changing technologies—big data, artificial intelligence, cloud computing, machine learning to name just a few.5 Most students—72 percent of those surveyed—believe their faculty too needs training in the use of technology for lecture delivery. A curriculum benchmarked to global standards also seems to be on top of mind for most students.6 It is time for Indian educators to not only disrupt the way they teach using advanced technologies, but to also play a key role in overhauling the curriculum. Efforts are evident, but the need is for a wider dissemination of advanced teaching tools and techniques.7

With technological disruption taking center stage in today’s workplace and various new tools such as mixed reality capabilities giving faculty the opportunity to offer students experiential learning, Indian higher educational institutions need to learn how to incorporate technology into their methods and curricula. But that’s not all; human skills such as communication, negotiation, and relationship-building play a role in career-building as well. How do institutions incorporate all these requirements into their faculty and curricula? We outline ways in which higher education can be upgraded to pave the way for an envisioned Educator 4.0 (see the sidebar, “Educator 4.0”).

Educator 4.0

The concept of Educator 4.0 is closely intertwined with Education 4.0—a future paradigm, wherein the learning and developmental needs of students (potential employees) will be in sync with technology-driven disruptions, specifically Industry 4.0.8 The Educator 4.0 would ideally:

- Incorporate Industry 4.0 technologies such as robotics, 3D printing, and mixed reality capabilities into their teaching methods

- Collaborate with established companies, start-ups, regulators, and alumni to harness various Industry 4.0 technologies, data, and new-age content

- Establish the blueprint for lifelong learning and development that transcends a single discipline or specialization

Solving the Indian higher educator conundrum

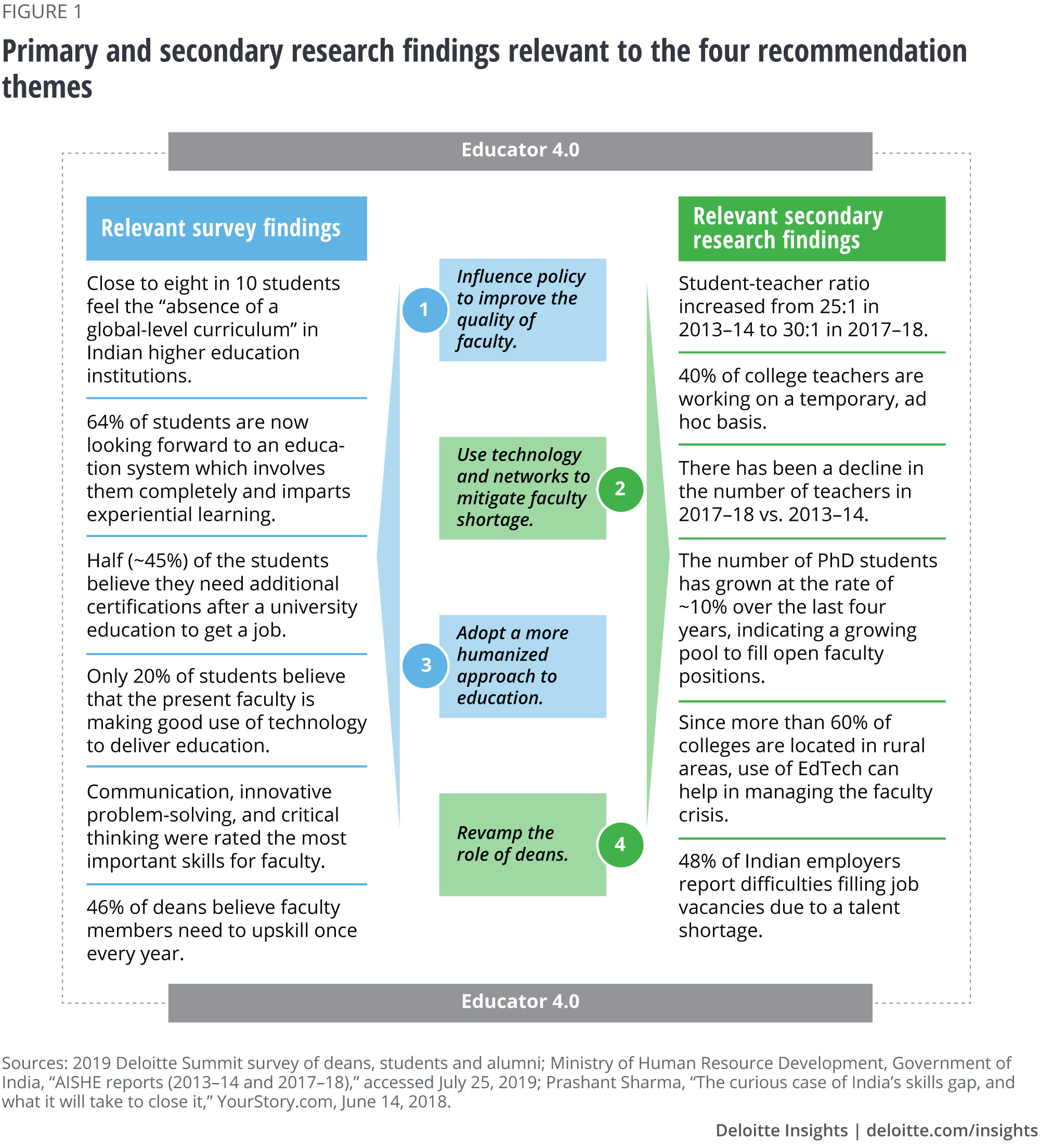

Based on extensive secondary research using data analytics and visualization9 as well as the insights generated from the Deans Summit 2019 in Deloitte,10 we have come up with four broad recommendation themes that converge on the vision of “Educator 4.0” outlined earlier.

Influence policy to improve the quality of faculty

Despite efforts, there has been little improvement in the quality of teaching at most Indian colleges (barring central universities or autonomous institutions).11 The dominant constraints seem to originate more often within academic institutions than outside of them. During the lab discussions at the Deans Summit, participants said that the challenge lies not just in technology adoption, but in the very mindset of faculty in terms of openness to embracing new technology and breaking hierarchical structures that restrict collaborative work.12

Policy-driven changes can therefore play an enabling role in breaking these barriers and reorganizing teams to make education more responsive to students’ requirements. In our survey, “faculty with research orientation” and “more practical courses than theory” came out as top factors that can bring in change and improve the quality of education. As one dean at the summit said, given the asymmetric capital allocation to research in response to changes in the global markets, there is a need to influence policy and maintain a fine balance between teaching and incentivizing research.13 Favorable policies in the form of research grants or incentives may help encourage higher educational institutions and universities to enable their faculty to go for training and enrichment. In addition, building centers of excellence (CoE) within academic institutions, establishing industry connects and interfaces, and nurturing more robust interactions over industry-sponsored research are other ways to enhance the quality of faculty.

Use technology and networks to mitigate faculty shortage

Technology can be a key enabler for institutions trying to overcome the shortage of skilled faculty and provide training that meets the talent needs of businesses today. A course well-endowed with technological tools (tablets, educational software) can not only cater to the “individualized” needs of the student but also enhance the teaching experience for the educator. Platforms such as STRIVR that offer end-to-end learning experiences are already revolutionizing training and professional development in the United States by using virtual reality.14 Additionally, online programs such as the Georgia Tech OMSCS course (Online Master of Science in Computer Science)—the largest master’s degree program in computer science—are not only a good way to refresh one’s technical abilities but are also accessible to many across the world.15 In India, for instance, leading tech companies have already established digital education initiatives aimed at training students on the latest Industry 4.0 technologies, as well as enhancing faculty capabilities by assisting them on course content strategy and experiential learning.16

Other solutions include more autonomy for faculty to pursue research opportunities with research institutes17 and recruiting quality faculty from a growing pool of available candidates.18

Alumni also form a significant cog in this wheel—they are intrinsic to students building transformative relationships that matter in the long run. Our survey shows that 84 percent of alumni are willing to support their alma mater financially as well as through academic-corporate connects.19 Quite a few reputed institutes in India involve their alumni through investments in incubation and research centers.

Adopt a more humanized approach to education

One thing that stood out in our interviews is educators calling out the necessity of helping students develop human values. With organizations moving from employee experience to human experience, soft skills and emotional intelligence are essential for building long-term careers.20 These skills also come in handy for building lasting relationships that can be a critical foundation for students, especially in the context of the psychosocial pressures they operate within.

One challenge is to help faculty develop skills that will allow greater bonding with students and understanding their beyond-the-classroom needs. Therefore, there is an urgent need to develop and maintain a continuum of learning and development opportunities for faculty in these areas. This would involve specialized classroom-based trainings on soft skills, live, simulation-based trainings, and observation of the best practices followed in corporate offices. Microcredentials—which some niche US digital education organizations have been experimenting with and piloting—can similarly help Indian higher education faculty to acquire a range of new competencies from several digital education platforms.21

“It is not just about creating employability … Where is the life of the mind?”–2019 Deloitte Deans Summit participant

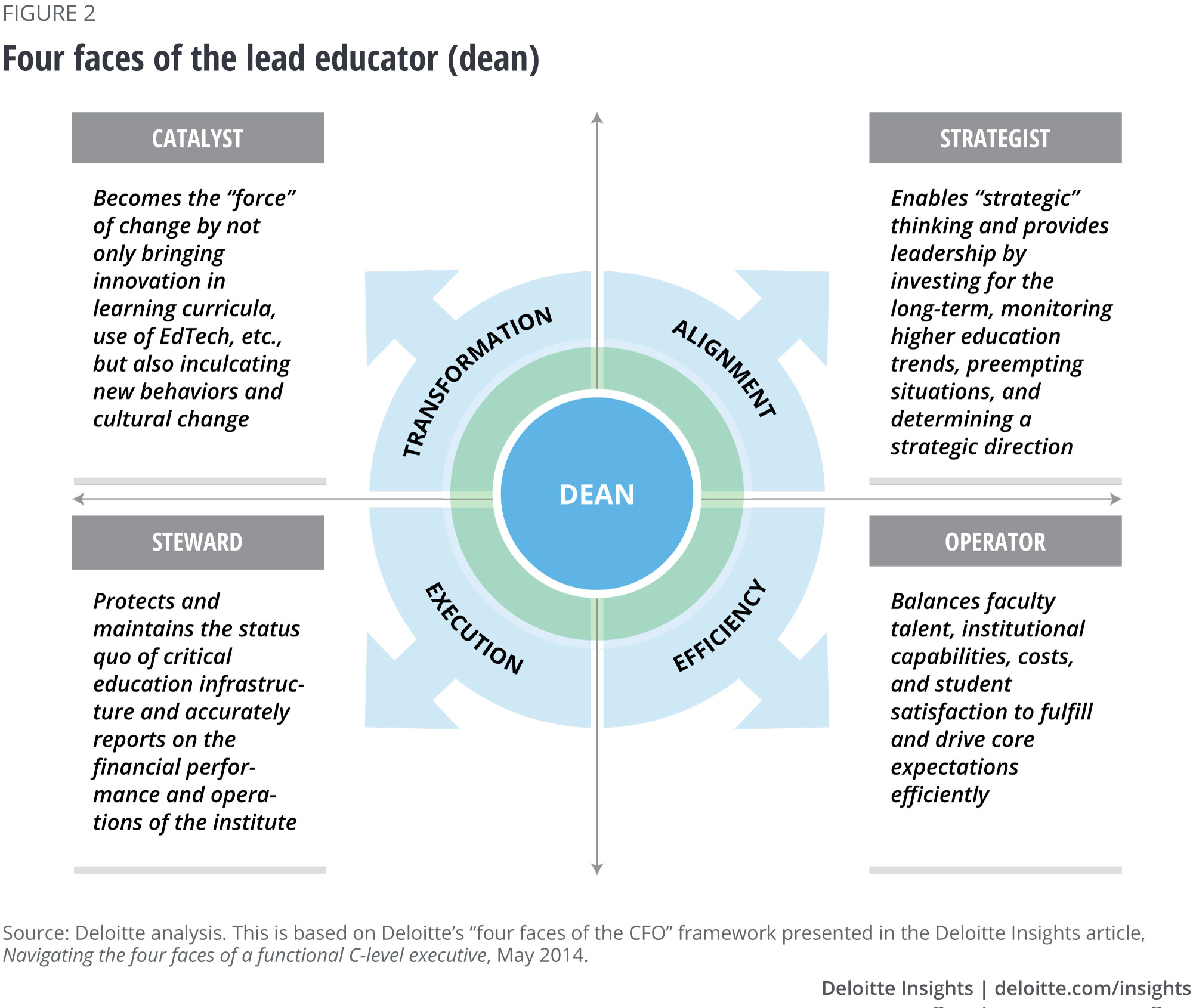

Revamp the role of deans

With the changing realities of learning, there is a need to focus on the four faces of the lead educator—a prioritization based on roles, elaborated in figure 2. Deans and directors need to begin analyzing the multiple roles they currently play, prioritize focus areas, and balance these in the light of the external forces that are disrupting education today.

For example, Dan, the dean mentioned in the introduction, may have immersed himself in the steward and operator roles ever since he joined the institution. But changing times call for a role transformation. From spending 60–70 percent of his time focusing on tasks related to execution and efficiency, Dan may now need to pivot to the catalyst and strategist roles in line with his institution’s need for a focus on transformation and alignment in the face of disruption. This means a large proportion (60–70 percent) of his time and effort should go into catalyzing behaviors and culture which lead to innovation and into enabling strategic thinking that builds long-term resilience against disruptive change.

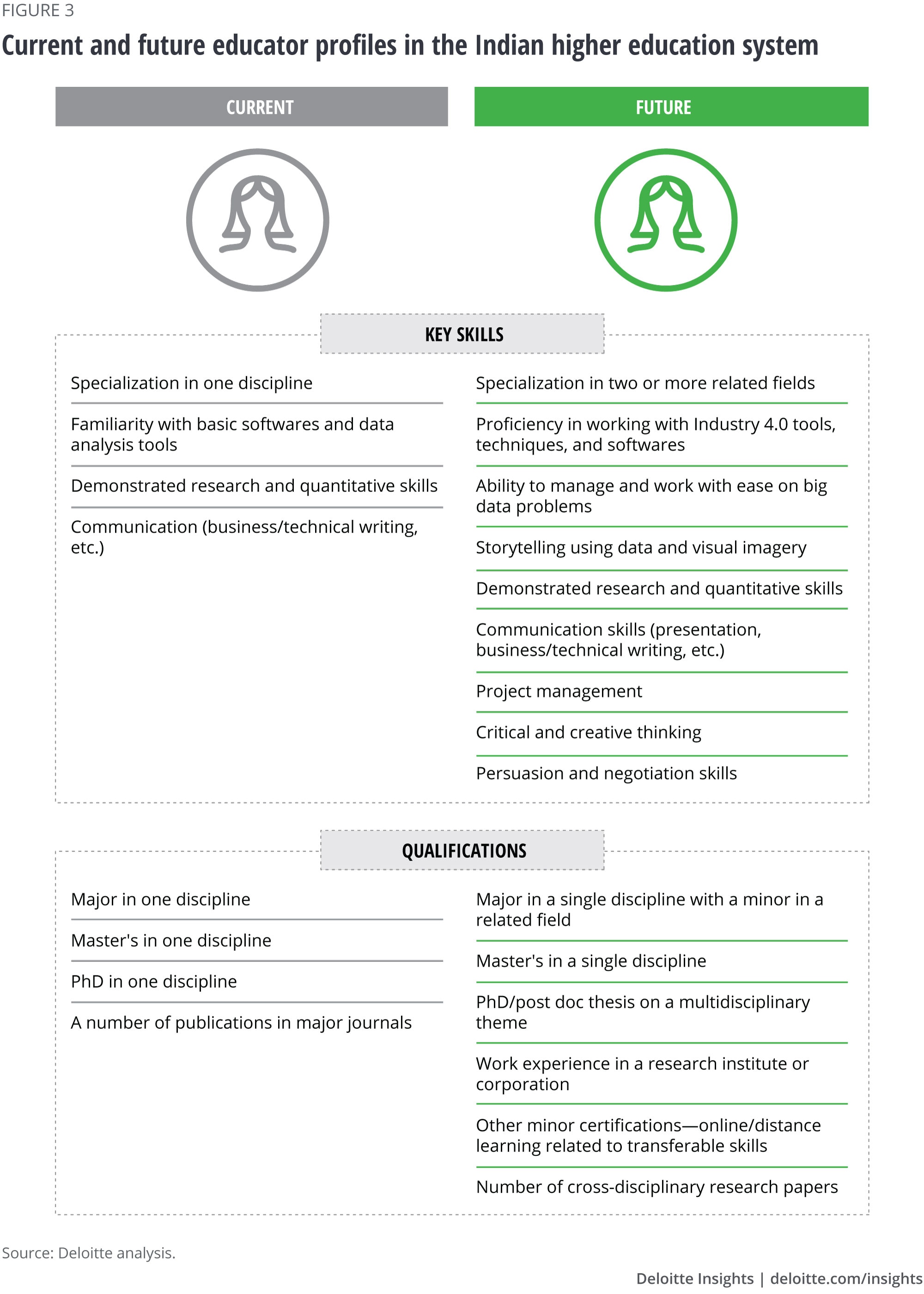

The Indian Educator 4.0—Imbibing a multitude of skills catalyzing gradual transformation

Considering the dynamic changes affecting the future of Indian educators, the nature of skills, education, and experience that faculty will require and the time they will need to spend on various pedagogical activities are some of the elements that are likely to undergo changes. Considering this, a generic profile of the future Indian educator will look different (see figure 3).

A cross-hybridization of skills is imminent. Our survey results point out that in addition to research and quantitative skills, a typical professor will also need to be well-versed in soft skills as well as proficient in the use of the latest tools and software. This can likely help the professor make teaching more of an experiential affair.22 Familiarity with managing, analyzing, and weaving a story out of big data will likely be an advantage. All of this will likely translate into renewed priorities for professors with regard to day-to-day activities. Instead of spending more than 70 percent of their time on teaching and administration, they will now spend a third of their average day on research and consulting and learning and development. EdTech will play a major role in this role revamp, given that familiarity with Industry 4.0 tools, techniques, and processes will be a prerequisite.

Skills can only be acquired and honed over time through education and exposure: Professors will have a minor degree in two or more of the related disciplines, with ad hoc online courses and certifications filling the education gap. They should also have demonstrated technical writing skills in some of their cross-disciplinary research papers. This development will be in sync with work becoming increasingly multidisciplinary. In addition, experience in research institutions or multinational corporations might also receive greater weightage in faculty selection.

Creative, critical, and strategic thinking skills will be highly valued among future educators across all major disciplines. These transferable skills will enable them to pivot their roles from pure teaching and administrative work to become a strategist or catalyst for their institution, apprising students with the realities of the modern workplace and helping them embrace the changes effortlessly.

Realizing this vision of the Indian Educator 4.0 may seem like a distant possibility now, but with steady espousal from various stakeholders in the education and business ecosystems, it is feasible.

© 2021. See Terms of Use for more information.

Explore more on higher education

-

Delivering on the promise of Indian higher education Article5 years ago

-

3D opportunity for higher education Article6 years ago

-

The Reimagine Learning network: Tackling persistent problems Article5 years ago

-

Student success by design Article6 years ago

-

Future of public higher education Article6 years ago

-

K–12 education: Old debates yielding to new realities Article7 years ago