Home and stock ownership are primary drivers of wealth

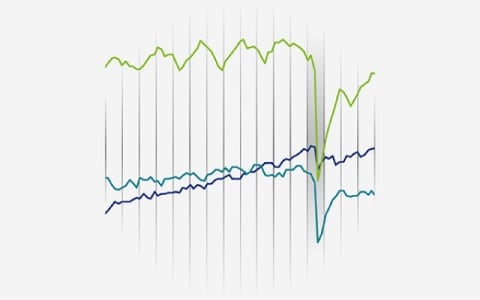

Let’s first examine the evidence that homes and stocks are major contributors to growth in US household wealth. Between Q4 2019 and Q4 2021, total US household wealth rose by US$32 trillion after dipping during the COVID-19 recession in Q1 2020. Furthermore, the pace of growth in net worth was much faster during the bounceback after Q1 2020 than it was in the pre–COVID-19 expansion.8

According to a US Federal Reserve analysis, 80% of the post–COVID-19-recession growth in wealth between Q4 2019 and Q1 2021 (the most recent data at the time of the study) can be attributed to an increase in asset prices, particularly to increases in real estate, stock, and bond value.9 Though equity prices fell sharply between February and March 2020, they rebounded quickly after the Fed, US Treasury, and Congress took steps to stabilize financial markets.10

The value of real estate holdings increased 12.6 percentage points between Q4 2019 and Q1 2021.11 This rise, according to the Fed study cited above, was almost entirely due to a 13% increase in median home prices during 2020 and 2021, not to an increase in homeownership rates.12 Recovering stock markets provided even more of a boost.

These trends tell us that owning a home and/or stocks gives households a distinct advantage in growing wealth. It’s not that a higher percentage of people own homes or stocks today than they did in early 2020—as shown below, ownership rates have been mostly flat—but that those who did enjoy a dramatic rise in the value of those assets since then.

Despite a narrowing of the wealth gap postrecession, home and stock ownership among racial/ethnic minorities still lag those of white households

To understand whether the postrecession growth in US household wealth affected racial/ethnic wealth disparities, we examined data from the Federal Reserve Board’s most recent 2019 Survey of Consumer Finances (SCF), a triennial survey providing detailed financial data on households by race/ethnicity and age. Unsurprisingly, the numbers show clear differences in wealth between households that the SCF classifies as white, Black, and Hispanic (a fourth “other” category was not included in our analysis, as it is too heterogenous to allow for meaningful comparisons. See the sidebar for a full explanation). These gaps, however, are not constant over the years but widen and narrow in different time periods.

In the economic expansion before the COVID-19 recession, wealth disparities among races/ethnicities were on the rise. On average, white households added US$34,400 to their median real wealth between 2010 and 2019, while Hispanic households added US$17,100 and Black households only US$5,300. The standard economic measure of inequality—the difference between the median and the mean of each group’s income or wealth13—shows that wealth inequality just before the recession was much greater than income inequality, both between races/ethnicities and within each race/ethnicity (figure 1), although income inequality also rose during this time.14