Digital media trends The future of movies

14 minute read

10 December 2020

Chris Arkenberg United States

Chris Arkenberg United States David Cutbill United States

David Cutbill United States Jeff Loucks United States

Jeff Loucks United States Kevin Westcott United States

Kevin Westcott United States

Movie studios and distributors have taken a direct hit from the pandemic. In response, they now have an opportunity to revamp the business models of a time-honored tradition to better meet the demands of the digital world.

The impact of COVID-19 on movie theaters has accelerated two preexisting trends: More people are staying home to enjoy movies and other entertainment, and more studios and media distributors are developing their own direct-to-consumer streaming services. While theaters have suffered heavily from stay-at-home norms, studios have also been deeply challenged. Productions were halted, some of the most anticipated theatrical premieres were postponed,1 and more top studios had to forgo theatrical releases altogether and go direct to consumers to generate at least some income.2 After the pandemic is over, it is unclear what role movie theaters will play in consumer entertainment or to what extent the existing system of releases will have been disrupted.

Learn More

Explore the Digital media trends survey, 14th edition

Read the executive summary

Explore the Thinking Fast series library

Learn about Deloitte’s services

Go straight to smart. Get the Deloitte Insights app

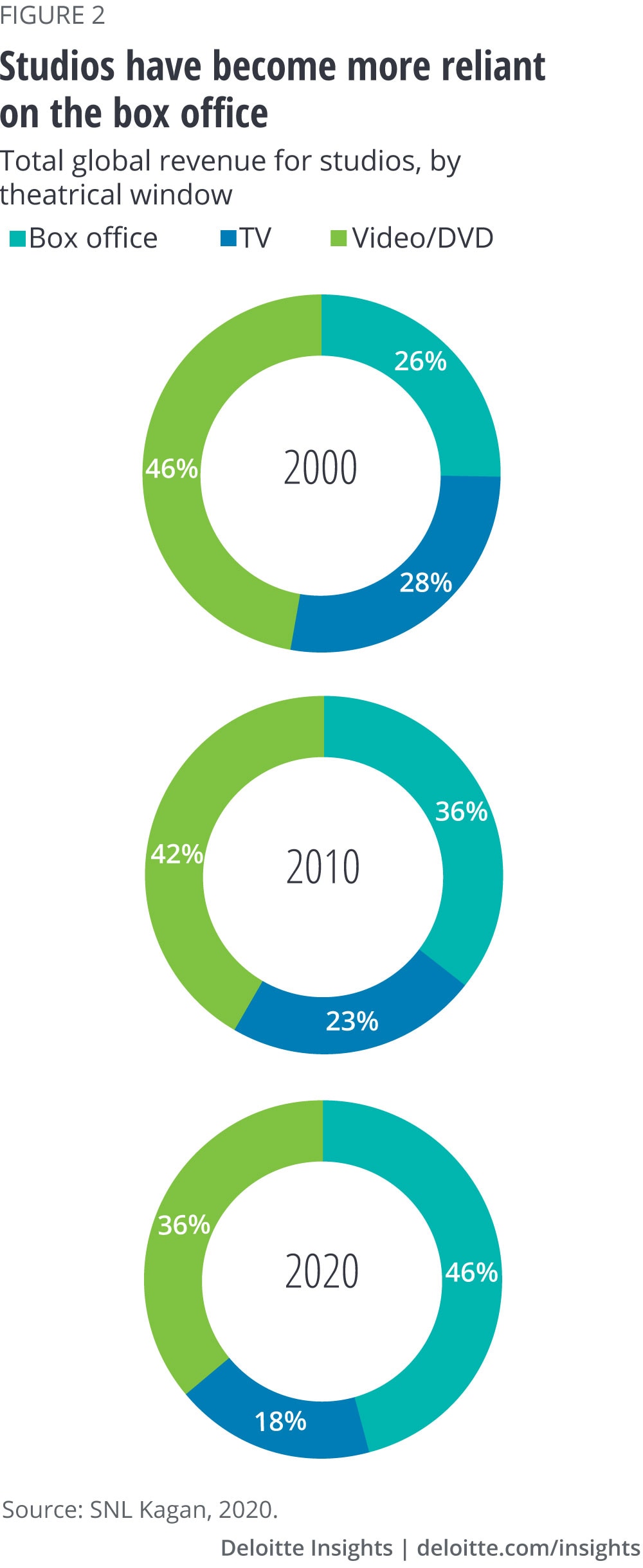

Studios derive almost half of their revenues from theatrical releases. Although the average number of movie tickets purchased by Americans each year has declined from 4.2 in 2009 to 3.4 in 2019,3 studio revenues are driven more by box office tickets now than they were 20 years ago.4 If theaters have a diminished role in the windowing system—the schedule of exclusive exhibition periods across theaters, home video, cable and TV, and streaming—it could force changes in how content deals are financed, what the terms for distribution look like, and how studios make money from their productions.

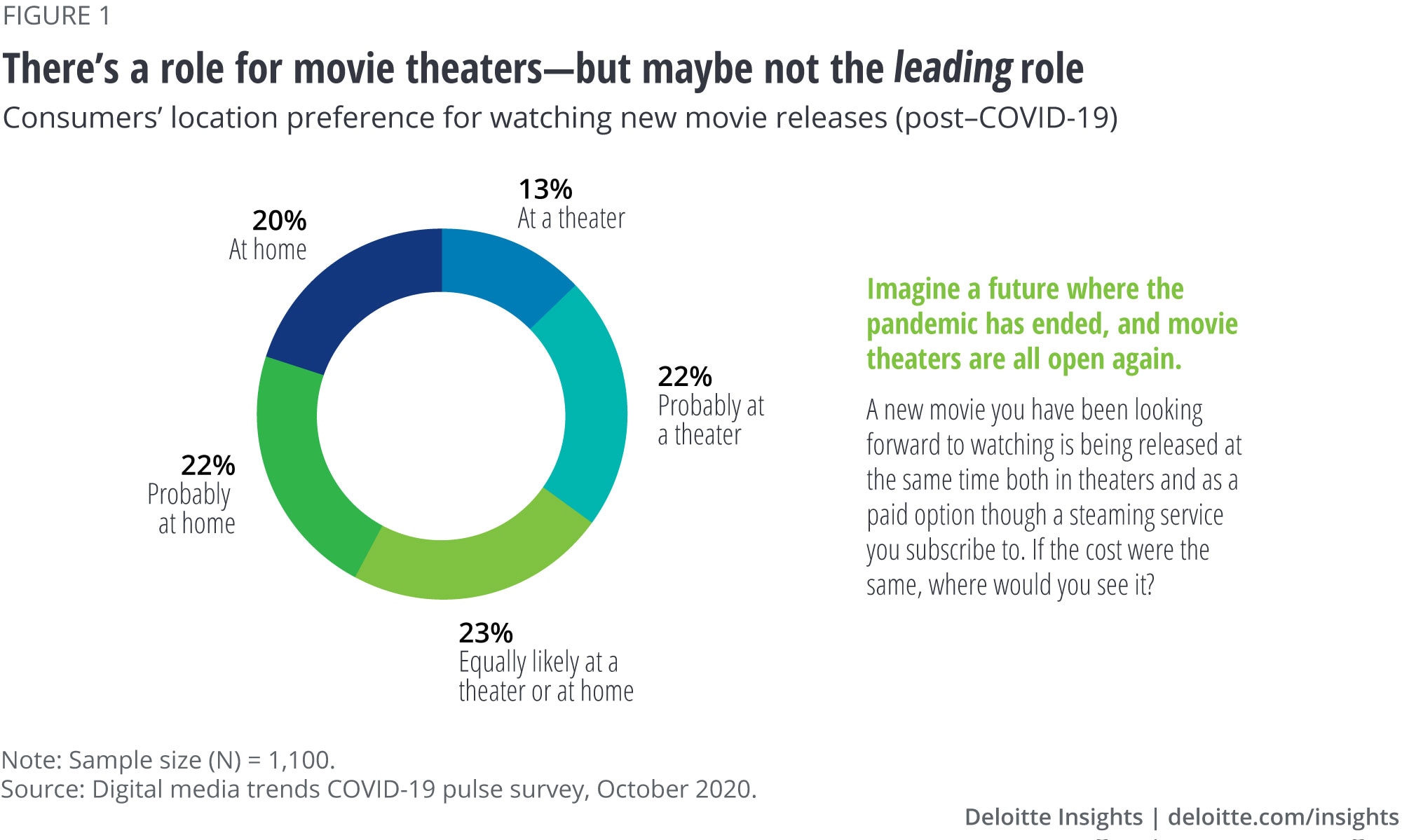

Although streaming may look like the obvious path forward, studios can’t fully monetize all their franchises and derivative content through streaming services, particularly if they don’t control their own distribution channels. For those that do, deploying streaming services is very costly. Many have yet to show much profit, despite their expanding market valuations.5 Early experiments with premium video-on-demand (PVoD), where first-run movies are offered directly to consumers on streaming services, have had mixed results during the pandemic. At the same time, if the pandemic were over, 68% of consumers want to watch at least some movies in theaters (figure 1).6 Clearly, it is not as simple as just shifting to streaming.

With more people opting for home entertainment experiences and more studios developing their own distribution channels, studios have a chance to reconsider movie windowing and revenue models. Is a movie only a “movie” if it is first released in a theater? Should some movies skip the theater and go directly to consumers via streaming and PVoD? Are there different forms of value that can be unlocked with direct-to-consumer services? These are questions studios should be asking at this unprecedented moment.

The right answers could hinge on a studio’s perspective about the future of content, how they reach and engage audiences, and how they shift to deliver ongoing value to consumers and subscribers.

The changing landscape of movies

Studios are very reliant on box office sales, which rose from 26% of total global revenues in 2000 to 46% in 2019 (figure 2).7 With almost half of their revenues from theatrical releases, studios are understandably concerned about upending a century-old model in favor of digital distribution.

Studios typically release new movies to theaters with an exclusive window: A film cannot be shown on any other channel during the theatrical release. On average, studios share 45% of box office revenue with the theater operator. Most movies make about 75% of total US box office revenue in the first 17 days (including the first three weekends), yet they can stay in theaters for another 60 to 75 days to capture the remaining 25%.8 The longer a movie runs in theaters, the more the revenue share shifts in favor of the venues.

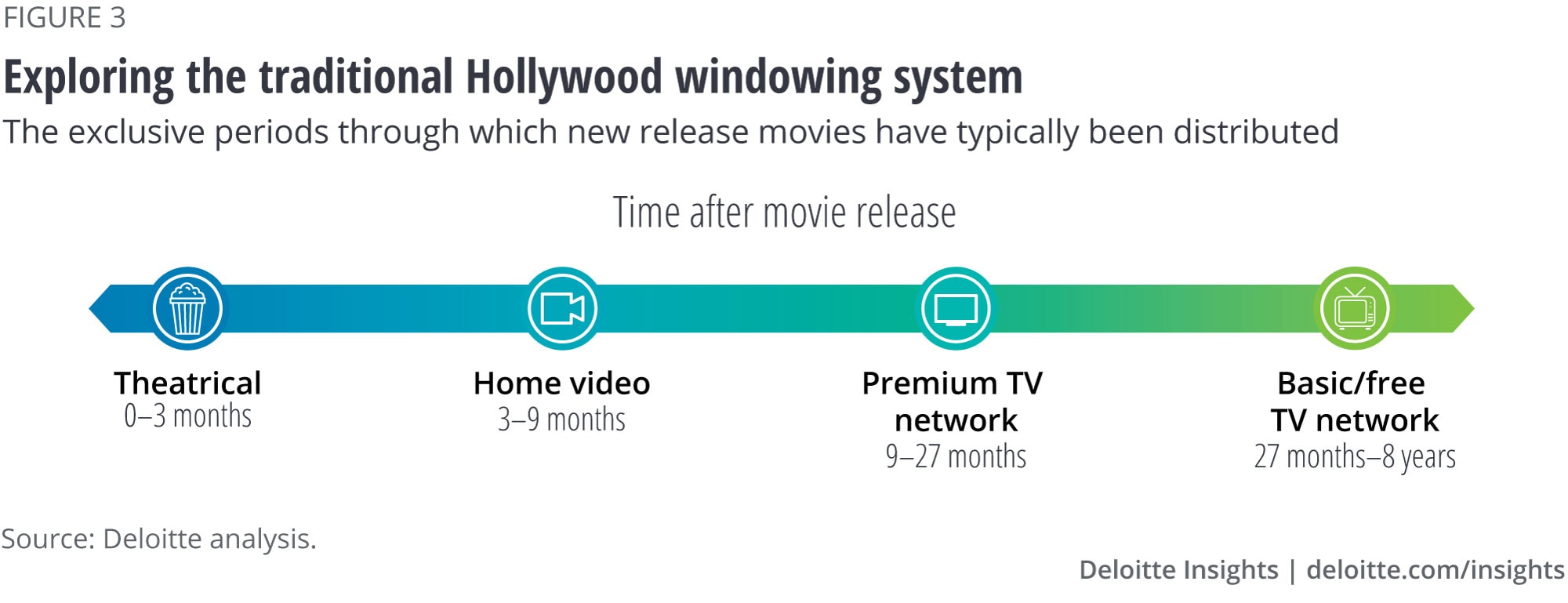

Although they are usually the first, movie theaters are just one of the windows that studios and distributors use to release films (figure 3). Traditionally, the windowing system has ensured that revenue generated by each platform is protected by rights to show movies during a particular time frame. For example, the theatrical window ensures movies are only available in cinemas over the first 90 days, followed by the home video and premium TV windows. They are not always distinct, however. Some overlap, while others, such as home video, may extend indefinitely.

Theatrical releases not only drive box office revenues; they also typically determine how revenue from subsequent windows are negotiated. For example, the license fee for TV windows is determined by the success of the theatrical release: the higher the box office revenue, the higher the license fee paid to studios. If more movies skip theaters or shorten theatrical windows in favor of digital platforms, fewer movies would likely be able to generate required box office results or reach minimums for TV deals. Likewise, movies still account for much of the daily scheduling on premium cable networks. Changes to the theatrical window—such as releasing a movie on PVoD instead of in a theater—could create a domino effect of change across other windows and put more pressure on the success of streaming efforts to compensate.

This shifting landscape puts studios in a difficult position. They may be able to reach more people through streaming services, particularly during the pandemic, but doing so could undermine theaters and the large revenues they generate. It could also affect revenue from other windows—if they choose to use them. Such considerations impact upfront financing of productions, existing distribution agreements, and licensing terms.

Arguably, exhibition windows have primarily been actuarial—a launch plan negotiated to anchor financing of productions and then monetize their steady release to different consumer segments. As on-demand streaming services have expanded, they have put more pressure on the traditional post-theater windows, such as premium and basic pay TV. In addition, consumers have come to demand instant access to services of all stripes. When convenience and immediacy are paramount, the time delays that consumers face with the windowing system may feel like unnecessary friction.

Enter premium video on-demand

The pandemic seems to be forcing the hand of major studios. They either lose money by delaying theatrical releases or launch first-run films directly to consumers over streaming services. According to Deloitte’s Digital media trends 14th edition fall pulse survey, only 18% of US consumers have attended a movie in a theater since the COVID-19 pandemic began.9 Even if they had the option, only 29% of consumers would feel comfortable going to a theater within the next month.10 Prolonged closures, and the reluctance of moviegoers to return to theaters when they reopen, have put theater chains under tremendous financial pressure.11

During the crisis, PVoD has emerged as a viable way for studios to reach movie fans, while also posing a challenge to the traditional windowing system. PVoD movies are available on subscription streaming services where consumers can view them at launch for an additional price of around US$20— often double the average theater ticket price12 but significantly less than the US$35 a typical family might pay at the box office.13

During the early phase of COVID-19 stay-at-home orders, Deloitte found that 22% of consumers had paid to rent or watch a PVoD movie, and 90% of those said they would do so again.14 As the pandemic has continued, studios have released more movies via PVoD, and viewership has grown. As of October 2020, 35% of consumers say they’ve watched a PVoD release.15

This growth is promising, but convincing the majority of consumers to pay a premium to stream a movie at home may take time. Among consumers who have not paid to watch a PVoD movie, cost was the top factor.16 This challenge could be greater when streaming services charge for PVoD movies on top of monthly subscription fees. However, consumer interest in PVoD could wane once the COVID-19 pandemic has retreated and movie theaters are considered a viable—and safe—option.

Perhaps the biggest question is whether studios can get the same revenues from PVoD they do from theaters. One benefit of PVoD is that studios can get a larger share of revenue. When movies are released in theaters, studios keep 55% of the box office revenue. With PVoD, that share is close to 80%. Studios could reduce the cost of theatrical distribution by shortening those windows to favor a PVoD release. A recent agreement between a major theater chain and a studio reduced the theatrical window to 17 days, after which movies would be available on PVoD.17 With theaters under pressure, studios could negotiate lower revenue share or lower guarantees.

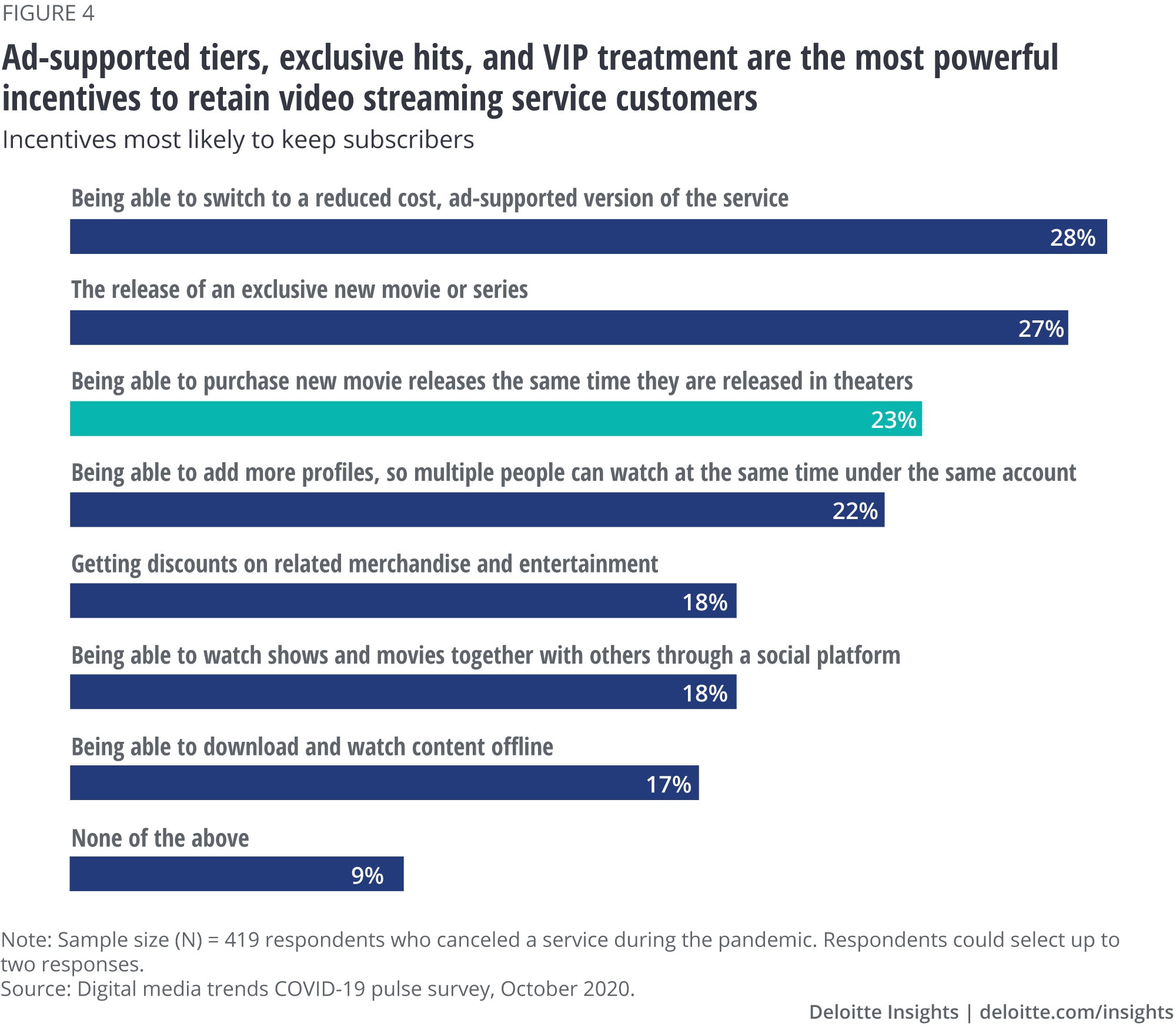

PVoD could help studios make their streaming services more valuable to subscribers, satisfy consumer desire for new content, and make them feel like a VIP. A direct-to-consumer release could frontload the cost of preparing a film for streaming distribution, both as a PVoD release and an ongoing part of the streaming catalog—a growing requirement for streaming video services. Studios could even consider developing windowing within their streaming services, staging releases across PVoD, basic subscribers, and ad-supported streaming audiences. For studios that have their own video streaming services, offering subscribers exclusive access to PVoD when a movie is released in theaters could be the kind of perk that could prevent churn (figure 4).

PVoD could help studios make their streaming services more valuable to subscribers, satisfy consumer desire for new content, and make them feel like a VIP.

Going direct: From revenue per window to revenue per user

The combined drivers of flattening theatrical revenues, rising in-home entertainment, and the shift to streaming distribution are putting greater pressure on the windowing system. For studios and distributors, direct-to-consumer distribution channels may require a strategic reassessment of monetization—and a willingness to shift their perspective. For example, streaming revenues may never directly replace those from theatrical and linear TV.18 So, what new kinds of value can a direct-to-consumer solution enable? How can studios and distributors move from revenue per window to revenue per user?

Just as streaming lowers the friction for audiences, it can also make it easier for studios and distributors to get more relevant content and advertising in front of the right audiences. Typically, digital services can generate much more data about engagement than theaters can provide, such as data based on content interests, demographics, and location. Leveraging data-driven insights can potentially reduce risks in content development and financing while enabling more effective targeting for ad-supported services. Studios could also use data to identify valuable segments such as “super users.” Deloitte has found that consumers who watched a movie via PVoD are more likely to have subscribed to additional paid services such as streaming video, streaming music, and gaming.19 This could lead to greater acquisition and retention for studios that offer broader entertainment packages.

For major studios with their own streaming services, PVoD can be a lever to attract new subscribers and retain existing ones with exclusive releases. The trend to develop original content as a lure for streaming subscribers will likely only continue, but providers may need to experiment with pricing and even ad-supported options to reach more segments. They may need better insight into which content attracts subscribers and keeps them on the service and which content doesn’t. Armed with this knowledge, studios can focus their dollars on content that contributes to profits.

Although only the largest studios control a streaming service, they also see the need for original hit content—a need they may struggle to fill. Smaller studios may be able to negotiate better terms with streaming services if they offer PVoD exclusivity though, again, they should weigh the costs against the benefits. Ultimately, trends in media consumption in an increasingly competitive landscape underscore the need for studios of all sizes to reconsider windowing. Studios now have an opportunity to take a more nuanced and measured approach to how different types of content may perform on different distribution channels.

A portfolio of content and distribution channels

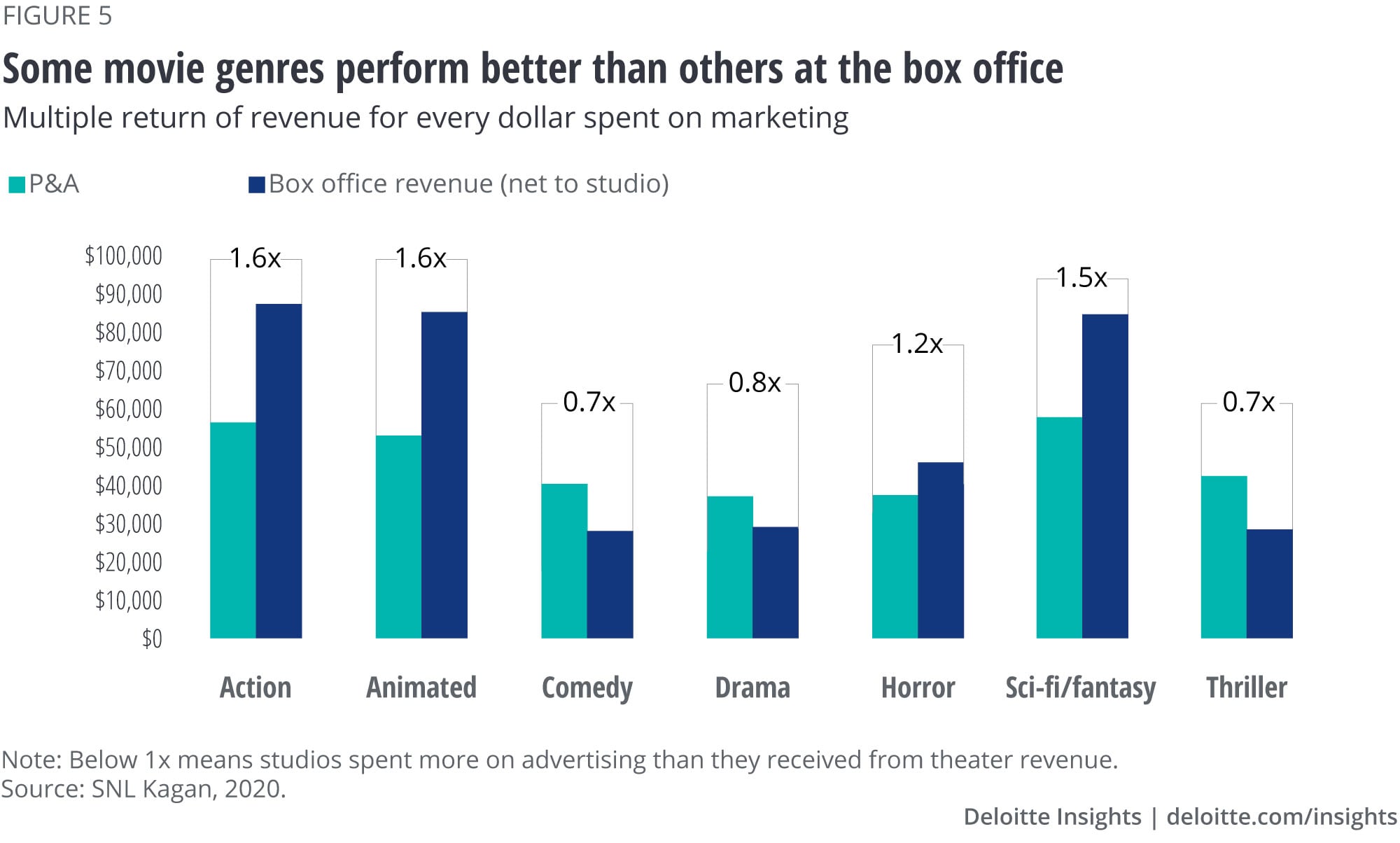

Although studios receive 45% of their overall release revenues from movie theaters, not all movies are theatrical successes. Relative to their marketing costs, action movies, science fiction and fantasy, and animated features show the strongest returns from movie-going audiences (figure 5).20 Comedies, dramas, and thrillers more often see negative returns on advertising dollars; they cost more to market than they earn in cinemas.

Given the variable performance of different genres, studios could use genre and film budget to determine the length and feasibility of theatrical runs. Some movies may be well-suited to big theatrical windows while others may have a shorter time at the box office—or none at all. The term “direct to video” has often had negative connotations, signaling a production not good enough for theatrical distribution. With Emmys and audiences piling up for streaming services, the same may not be true for “direct to streaming.”

The industry could benefit from reconceiving storytelling and cinema. By moving past the TV-or-cinema dichotomy, studios could pursue a more diverse array of storytelling vehicles. For example, they could increase development of shorter and less cost-intensive content types, attracting younger audiences and talent while leveraging social media and video-sharing platforms for distribution and promotion. Such pathways can reinforce larger franchises and promote or resurface more expensive original content such as features, films, and series. Studios should consider a franchise strategy that consistently engages fans with new content on multiple platforms, rather than waiting until a new movie is released.

The challenge for studios and distributors is to better understand which channel is appropriate for which kind of content, and how to match that with the right audiences. Data can help, but it may be more interesting to redefine content to focus on storytelling, entertainment, and audience engagement and retention, rather than on where it fits into exhibition windows or whether it debuted on TV or in movie theaters. This could enable studios and media companies to become more flexible and meet the evolving preferences of viewers.

Different strokes for different studios

The calculus will likely vary widely depending on the type, size, and reach of a given studio. Major studios and distributors with their own direct-to-consumer streaming services have greater capacity to change, but also carry higher risk and drag. Some are clearly focused on streaming subscriptions; others have retained elements of linear TV with ad-based models. All are weighing the costs of producing original content, licensing back catalogs, and adjusting consumer pricing. Although many young video streaming services are focused on subscriber acquisition, the looming battle is in retention.

To be successful, studios may need to move closer to their audiences and work to continuously provide greater customer value. Complicating matters, they are competing with tech and telecom giants that don’t need their media arms to turn a profit, because their main businesses lie elsewhere. The deep pockets and market power of these companies can put studios in a bind, whether they’re buying content, selling it,21 or producing originals.

Smaller studios looking for the best and most profitable distribution channels to reach target audiences have more flexibility to experiment but may need to clearly articulate their value to digital distribution owners. In some cases, they may sell content. In others, they may be brought on as production partners. Small studios could also benefit from moving past the TV-or-cinema dichotomy. They could consider ways to extend their stories and characters across video gaming, for example, or other immersive experiences, integrating multiple mediums and channels to tell stories and engage audiences. Their flexibility with how, where, and when movies are released can support greater options for their distributors. In addition, small studios could gain access to more cinema slots if large studios reduce their theatrical releases.

Not only is the calculus variable for studios, the math may be changing. Measuring box office tickets against streaming or PVoD revenues is not an apples-to-apples comparison. Direct revenues from streaming may be lower but they may be less volatile, replaced by more stable monthly subscriptions, similar to how boxed software suites have shifted to subscription services. Migrating to more streaming can offset other costs such as marketing for multiple release windows. Digital distribution can use data to better understand churn, incentivize retention, and make advertising more targeted and effective. Deploying a portfolio approach to content and distribution could allow bets to be spread better. For example, it could enable greater retention of niche audiences with more low-cost productions, rather than leaning so heavily into blockbuster box office hits. Each of these options can add more value to offset theatrical losses. Ultimately, studios and distributors have an opportunity to shift their objectives from maximizing the revenue of windows to maximizing the revenue of users—a key step in getting closer to their customers and delivering greater value.

Measuring box office tickets against streaming or PVoD revenues is not an apples-to-apples comparison.

When the pandemic lifts, there will still likely be a role for theaters. As more streaming services vie for compelling original content, many of the showrunners, screenwriters, and actors creating it are still drawn to the prestige of cinema. When people feel safe to assemble again, theaters could see a strong rebound. Studios will continue to deliver big theatrical experiences, but how theaters adapt and demonstrate value against a growing at-home market may likely determine their longevity. They should bear in mind that the overwhelming consumer trend of the digital era is about removing friction and enabling greater convenience. The windowing system should evolve, as it has with previous shifts in media and distribution. Studios and distributors, who see the value of controlling and capitalizing on the customer experience, can help drive that evolution. How quickly media and entertainment companies address their existing dependencies will likely play out in the shifting competition for audiences and entertainment.

Moving forward: Key considerations for studio executives

The pandemic has challenged many industries to rethink their business and operating models. Here are questions studios and movie distributors can work through to determine how distribution and revenue models may need to change going forward:

- If more studios can distribute directly to audiences, what is the unique role of the theatrical release? How can theaters offer a differentiated experience from the modern living room—and a differentiated window for studios?

- How could changes to movie revenue models influence how studios approach licensing strategies over a movie’s lifetime? How would these changes align with broader direct-to-consumer strategies?

- How can studios take a portfolio approach to movie distribution? In which instances are streaming and PVoD the best solution, and what are the trade-offs against other windows that may be profitable but declining?

- Will streaming and PVoD be able to fully replace theatrical revenues and will they cannibalize future revenue streams? Or is there a more nuanced and strategic way to think about the value of each?

- Amid almost universal streaming penetration, what is the role of the pay TV audience and the high margins they deliver to the industry?

- How can studios take a franchise-maximizing view that creates different forms of derivative content exclusive to theatrical releases while also creating other content to attract and retain subscribers to their fledgling streaming services?

- How can studios and distributors attract more creatives who may be interested in storytelling beyond the traditional TV-or-movie options?

While the pandemic has hit the movie industry hard, it also offers an opportunity for the business models of a time-honored tradition to loosen up and better meet the challenges of the digital world. Streaming is becoming a necessity, following fundamental shifts in content distribution and on-demand audiences. Navigating these shifts can require time and patience, and may challenge traditional ways of developing, distributing, and monetizing content. Media and entertainment companies able to see the opportunities in change and the value of thinking differently can be empowered to help define the fast-approaching future.

Explore the Technology collection

-

Unbundling the cloud with the intelligent edge Article4 years ago

-

Evolving partner roles in Industry 4.0 Article4 years ago

-

Data management barriers to AI success Article4 years ago