Brazil It’s still too early to cheer despite a rebound in the third quarter

While uncertainties around COVID-19 remain, the country’s economy witnessed a recovery of sorts in Q3. However, much needs to be done to ensure long-term success.

The recovery in economic activity in the third quarter of 20201 is welcome news for a Brazil trying to shake off a tragic year as COVID-19 continues to infect people and claim lives.2 Yet it is too early to predict the nature of the economic rebound or even if it will continue. First, as in other countries, the economic outlook in Brazil will depend on the trajectory of the pandemic. While there is positive news about vaccines,3 ensuring that a sizable share of the population is vaccinated involves logistical challenges4 and therefore, will take time. Second, the domestic demand outlook is likely to remain challenging. A weak labor market and uncertain economic prospects will weigh on consumer confidence and hence, spending. This, in turn, will impact businesses, some of which have already been hit hard by the pandemic. The scenario for external demand is not much better, the global economy appears unlikely to rebound quickly.5 Finally, as the focus shifts from the recovery to economic fundamentals, Brazil will yet again have to reconcile with its fiscal health, which has taken a hit during the pandemic as the government stepped in to support those impacted by the downturn.

Domestic demand aided the economy in the third quarter

Learn more

Explore the Economics collection

Learn about Deloitte's services

Go straight to smart. Get the Deloitte Insights app

Real GDP grew by 7.7% quarter-over-quarter6 in Q3 2020, a sharp rebound from the two previous quarters of contraction. The recovery in Q3 was primarily due to a strong rebound in domestic demand. Private consumption, which accounts for a little less than two-thirds of the economy, grew by 7.6% in the third quarter—a contrast to the previous two quarters of contraction (figure 1). While consumer spending has faced headwinds from labor market weakness and people’s fears of contracting the virus, fiscal support for vulnerable households has helped offset these problems. Government consumption and investments also aided the recovery in Q3 (figure 1) although both face headwinds—while government spending will have to contend with deterioration in fiscal health, the trajectory of business investment will depend much on the recovery in consumer demand in the economy. The external environment remains challenging given the shock to global economic growth; reflecting this, exports contracted by 2.1% in Q3.

The rebound in Q3 notwithstanding, the economy is not yet out of the woods. GDP is still 4.1% lower than prepandemic levels with consumer spending 6.4% below what it was at the end of 2019.

Consumers continue to face uncertainty

While many consumers appear to have ramped up spending in Q3, whether that momentum will continue is uncertain. Labor market weakness continues as unemployment rises. The unemployment rate (three-month moving average) rose to 14.6% in September from 14.4% in August; the figure was 11.0% at the end of 2019. The more worrying factor is the sharp rise in people dropping out of the workforce. The workforce (three-month moving average) in September was 9.1% smaller than in December of the previous year. This is reflected in the sharp decline in the workforce participation rate (three-month moving average) during this period (figure 2), which is not only a concern for short-term consumer spending outlook but also for medium-term economic growth.

Labor market concerns likely weighed on consumer spending in the latter part of Q3, as shown by retail sales data. Growth in volume and value of retail sales has slowed since July—retail sales volume grew by just 0.9% in October relative to September. It’s not just economic woes, however, that are preventing consumer spending from recovering fast; the virus, too, is playing a role. Consumers appear to be shying away more from spending on certain services such as recreation and travel—most likely due to fears of the virus—than they are from spending on goods.7 Revenues of accommodation and food services businesses in September were 36.6% lower than December 2019 while air transportation revenues were down 65.2%. No wonder then, that, consumer footfall at retail and recreational places as of November is still down 13% from prepandemic levels.8

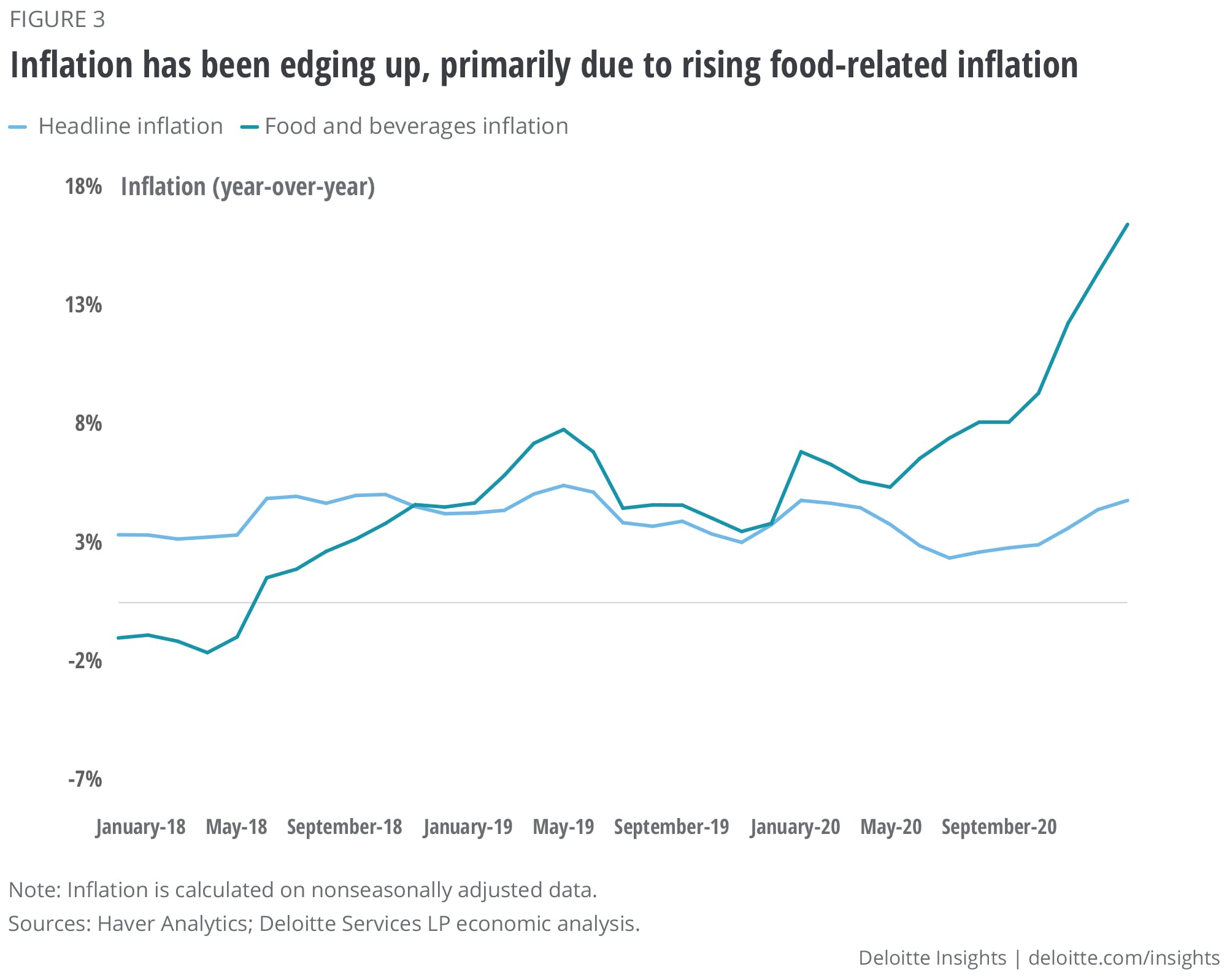

For households at the lower end of the income spectrum, two other concerns will likely weigh on spending in the near term. First is the reduction in monthly stimulus checks to vulnerable households. The value of these transfers for each household has halved to US$55 per month since September and may be withdrawn by the end of the year. Second, real earnings have been hit by rising price pressures in recent months. Headline inflation has been heading up steadily since June, primarily due to rising food-related inflation (figure 3). Prices of food and beverages, for example, were up 16% year-over-year in November, the sharpest increase in about 17 years.

Manufacturing is faring better than services, but uncertainties for businesses continue

The uncertainty in domestic demand, especially consumer spending, doesn’t make it easier for businesses to operate, and more importantly, expand. Data from the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics’ monthly index tracking revenues from key services sectors reveals that despite a rebound in Q3, the index is still 9.7% below December 2019.9 Worst affected are accommodation and food services and air transport (figure 4)—not surprising, given the difficulties of social distancing while eating out, staying in hotels, and traveling on a plane.10 With the pandemic still a key factor, expectations haven’t improved; business confidence in the services sector remains at a level that is net pessimistic.11

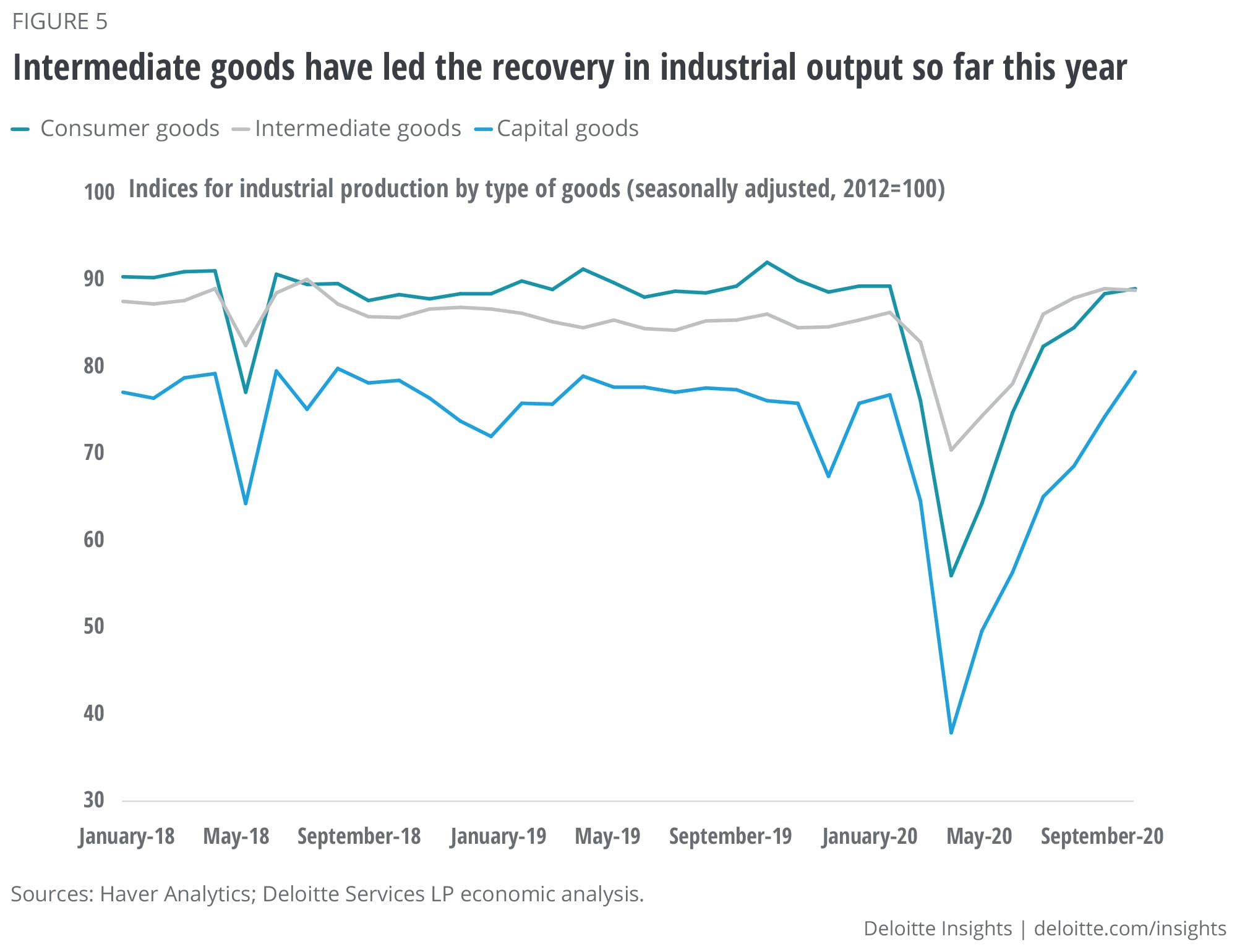

Manufacturing has fared better than services, with output steadily recovering from April’s lows—output is now higher than what it was at the end of last year. Confidence among manufacturing businesses, as measured by the Getulio Vargas Foundation (FGV), has turned to net optimism since September (in contrast to services businesses). In fact, the FGV index is now at its highest level since mid-2010.12 As manufacturers respond to pent-up demand, capacity utilization has gone up and at 80.3% in October is now at its highest level since April 2015. Overall industrial production, however, continues to be weighed down by volatility in mineral extraction. That is most likely due to shaky global demand and prices for minerals such as oil and gas and to a lesser extent, iron ore. This is unlikely to change in the near future given economic uncertainties in the global economy. Also, analysis of industrial output by type of goods reveals that intermediate goods have performed fairly well while output of consumer goods—both durables and nondurables—continues to face pressures from weakened consumer demand (figure 5).

Short-term policy support can only go so far

Monetary and fiscal policy have both been proactive during the pandemic.13 The government has provided fiscal support worth about 12% of GDP, and Banco Central do Brasil (BCB) has chipped in with 250 basis points worth of rate cuts and liquidity support. The question is, will more follow? That may be unlikely. First, a rise in inflation will likely make the central bank more cautious in easing rates further. While core inflation is still low—2% in November—headline inflation and inflation expectations have been going up since the middle of the year due to a surge in food prices. So, even though BCB has retained its accommodative stance to support the economy, it hasn’t cut rates since August. It is likely that the central bank will look at the inflation data and how it moves relative to its target (2.5%–5.5% for 2020 and 2.25%–5.25% for 2021) before easing further. And it will also keep an eye on the lagged impact of rate cuts on economic growth.

The challenge for fiscal policy is greater. First, the economy entered the pandemic on the back of a high government debt-to-GDP ratio. While reforms such as the pensions overhaul in 2019 reassured investors, the government will be aware of what happened in 2014–2016 when the lack of a fiscal reform plan brought in rating downgrades and surging bond yields. Second, given a high dosage of stimulus this year, fiscal health has deteriorated further (figure 6). For example, despite some improvement in Q3 due to rising revenues as the economy grew, the budget deficit was 17.3% of GDP, much worse than the annual 5.4% deficit in 2019. While the deficit is expected to fall from this level due to the recovery in GDP from the lows of Q2, it is likely to continue to remain high in the near to medium term. Therefore, the need for more borrowing is unlikely to ease. The International Monetary Fund forecasts net general government debt to rise to 82.8% of GDP over the next five years.14

The route to sustained recovery for Brazil, therefore, is not merely continued policy support, although that will undoubtedly help in easing economic pressures in the near term. The key for better medium- to long-term economic success lies in reforms, especially in enhancing competitiveness and fiscal health. Not only will that likely ensure a rise in long-term potential GDP growth, but is expected to also draw adequate support from investors, thereby keeping borrowing costs low.

© 2021. See Terms of Use for more information.

Explore the Economics collection

-

A view from London Article3 days ago

-

Economics Insider Collection

-

Federal Reserve monetary policy in the time of COVID-19 Article4 years ago

-

South Africa economic outlook, November 2024 Article4 months ago