Asian consumers Short-term risks may be a niggle this year

8 minute read

14 February 2020

In Asia, consumers are facing slowing economic growth and incomes this year. In some economies, household debt is also high. And any escalation of tensions in the Middle East may well topple the inflation applecart too.

As the memories of New Year’s Eve festivities recede from people’s minds, the dreary motions of everyday life take over. In Asia, as in other parts of the world, consumers are hoping for a better year—more jobs, more incomes, more wealth, and perhaps, less uncertainty. Yet it is less of hope and more of underlying economic and financial conditions that will determine Asian consumers’ prospects in 2020. While the economic outlook for Asia is favorable over the long term, with expectations of healthy economic growth, rising incomes and wealth, and an expanding middle class working in the region’s favor,1 there are a few risks in store this year. And in the spirit of the great John Maynard Keynes, it is worth looking at these near-term risks for they may well impact the fortunes, thereby spending and investment decisions, of Asian consumers this year.

Learn more

Explore the Economics collection

Learn about Deloitte's Services

Go straight to smart. Get the Deloitte Insights app

So, what do Asian consumers need to be wary of in 2020? Economic growth and uncertainty related to international trade is a key concern. While there are hopes that trade disagreements among major economic powers, especially the United States and China, will get resolved,2 it is still early days to say anything. Until a resolution is reached, these tensions will weigh on trade and investment in Asia and likely on the region’s economic growth, labor market, and personal incomes. And with household debt high in some economies, any decline in income growth will only add to consumers’ woes. Consumers in many parts of the region are enjoying low interest rates,3 but if tensions in the Middle East escalate, crude prices will likely rise, causing inflation to flare up. In that case, central banks will be forced to raise interest rates, thereby pushing up the cost of borrowing and repaying debt for consumers.

Keep an eye on economic growth

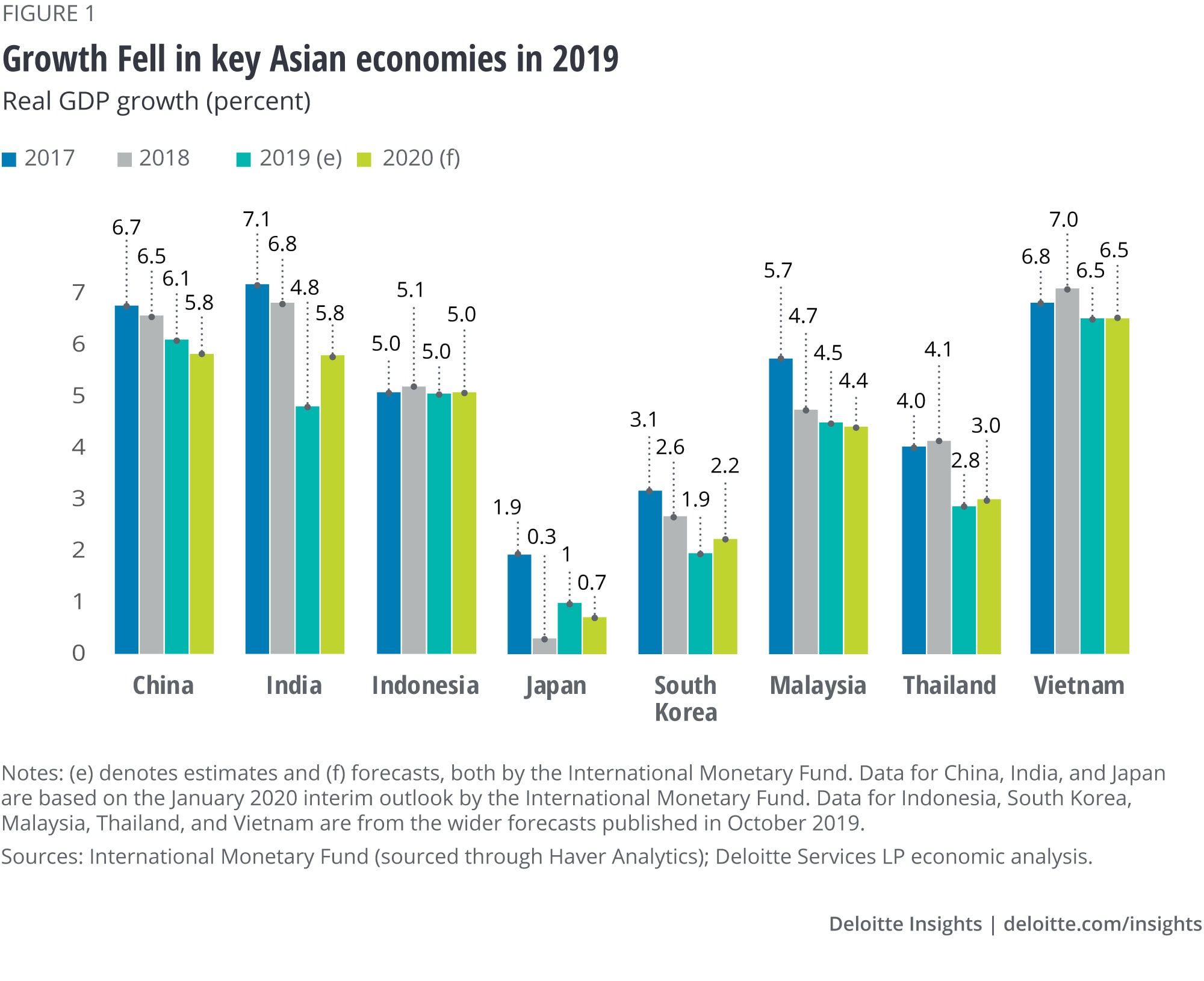

Strong growth due to fiscal and monetary sops in the earlier part of the last decade—to overturn the worst effects of the Great Recession—has given way to slower, yet likely more sustainable, growth in Asia. This trend is likely to continue into 2020, according to estimates by the International Monetary Fund (IMF).4 Emerging and developing economies5 in the region grew by an estimated 5.6 percent in 2019, down from a 6.4 percent rise in 2018. Overall, the region’s estimated growth in the last five years of the decade (6.4 percent) is lower than in the first five years (7.6 percent). Specifically, growth in China has been slowing steadily—by more than 4 percentage points over 2010–2019—and is expected to decline further this year as the economy matures, credit-fueled expansion slows under the weight of rising debt, and trade tensions with the United States add to uncertainty. In India, disruptions due to demonetization, introduction of a goods and services tax, and deterioration in banks’ asset quality have pushed growth down to an estimated 4.8 percent in 2019 from 8.2 percent in 2016.6 Economic activity has also lost momentum in Indonesia, a key Asian market, with growth slowing from an average of 5.8 percent per year in 2010–2014 to an estimated 5 percent in the following five years. The trend is similar for Malaysia.

For developed markets such as Japan and South Korea, growth is unlikely to pick up sharply this year. While Japan is still struggling despite years of quantitative easing to escape deflationary pressures, trade tensions have weighed on South Korea’s economy (figure 1).

Income growth has slowed in major economies

Slowing growth in key economies has impacted labor markets there. In India, for example, unemployment was 7.7 percent in December 2019 from a low of 3.8 percent in July 2017.7 In China, employment growth has been steadily declining since 2015—in fact, employment contracted by 0.1 percent in 2018. Unemployment has picked up, albeit slowly, in South Korea since August 2019. And in countries such as Malaysia, although unemployment has held steady of late, the figure is relatively higher than in the first half of 2010–2019. Given that GDP growth is unlikely to swing up sharply in 2020, improvement in labor-market conditions will likely only be gradual.

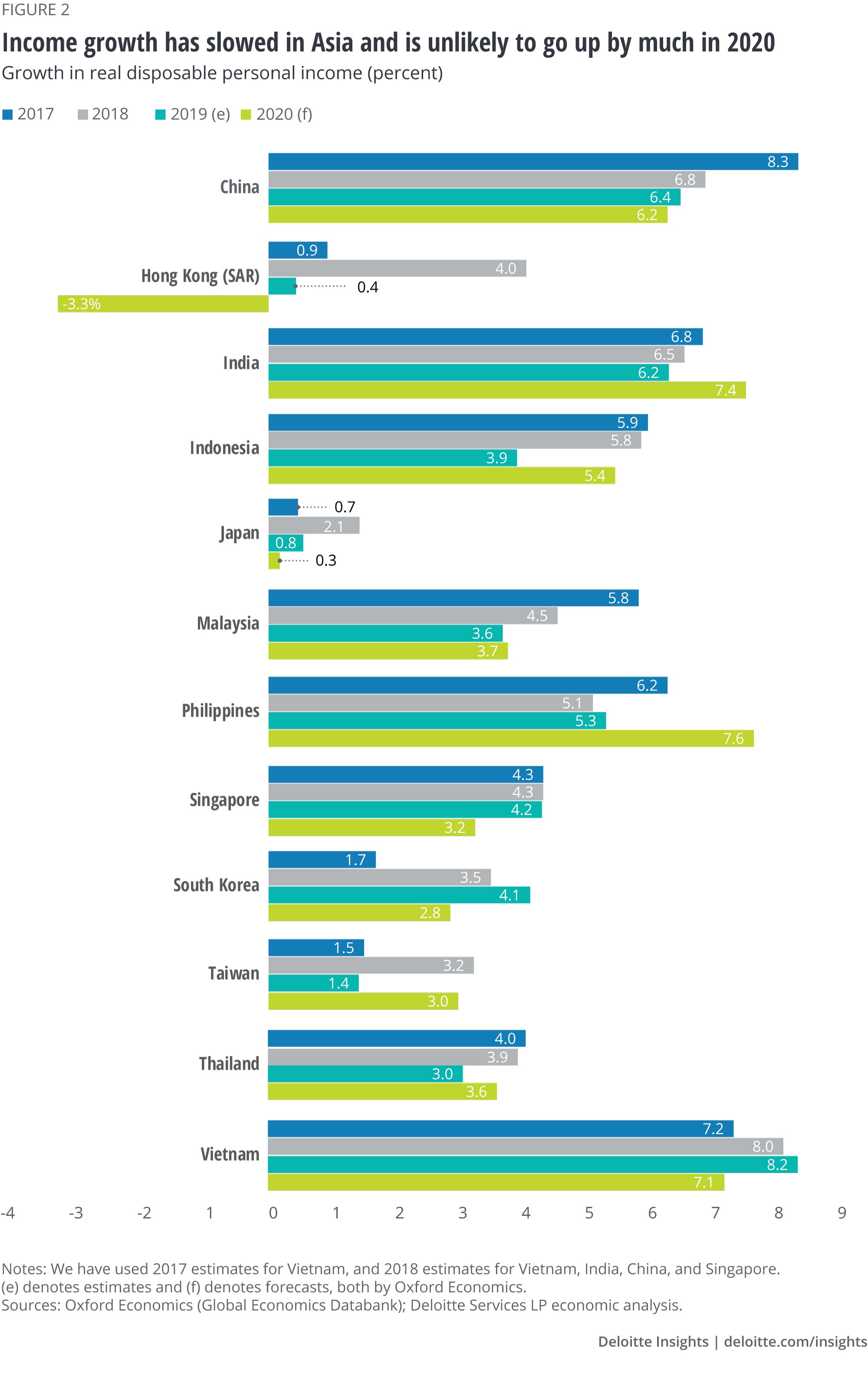

Slowing GDP growth, along with its impact on labor markets, has weighed on income growth in key economies in the region. According to estimates by Oxford Economics,8 growth in real disposable personal income in China is estimated to have fallen from an average annual rate of 11.4 percent per year in 2010–2014 to 7.0 percent in 2015–2019.9 Relative to 2018, growth in real disposable personal income in 2019 is estimated10 to have slipped in quite a few major economies in the region; it likely fell the most in Hong Kong (SAR), followed by Indonesia, Taiwan, Japan, Thailand, and Malaysia. Oxford Economics’ forecasts for 2020 is a mixed bag—while real incomes are expected to grow faster year on year in countries such as India and Indonesia, they will likely not in China, Japan, and South Korea (figure 2).

Slower income growth and labor market strains, in turn, have slowed the pace of growth in consumer spending. Passenger vehicle sales fell 18 percent in India between April11 and November 2019 compared to a year before.12 In China, growth in the value of retail sales picked up in the first quarter of 2019 but has been on a broad downward trend since. A similar trend is evident for retail sales volumes in Indonesia and Thailand. In Japan, retail sales growth picked up sharply in September, before the sales tax hike in October 2019,13 only to then contract in October and November. In Hong Kong, political tensions took a toll on tourism and consumer spending.14 By November 2019, retail sales were down 32 percent from December 2018.

Don’t forget household debt

For consumers in economies such as South Korea, Thailand, Malaysia, Taiwan, and China, there is yet another worry—high household debt. Household debt in these economies and a few others (figure 3) has surged over the past two decades, first picking up pace in the years leading up to the Great Recession and then in the subsequent recovery as governments there turned to consumers to drive economic growth through easy credit and fiscal incentives.15 The rush to take loans for everything from houses to cars pushed up household debt. Between 2010 and 2019, for example, total household financial liabilities are estimated to have grown by an average annual rate of 19.3 percent in China, 13.0 percent in India, 8.7 percent in Malaysia, and 8.4 percent in Thailand.16 With incomes not rising by as much as debt, households’ debt burden has gone up.

Interestingly, while China’s household debt burden appears less than some of its Southeast Asian neighbors’, the surge has happened over a short period. In 2005, for example, household financial liabilities in the country amounted to 29 percent of disposable personal income; by 2019, that figure is estimated to have increased more than threefolds to 88.5 percent. While the risk from high debt is likely manageable in a low interest rates environment and a strong labor market, any uptick in the cost of repaying debt and strains on the labor market may take a toll on households and, hence, consumer spending.

Geopolitical risks may put inflation back in play

Consumers in major Asian economies enjoyed lower cost of borrowing in 2019 than in 2018. The Reserve Bank of India, for example, cut its key policy rate by a total of 135 basis points in 2019. Central banks in Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Thailand, and South Korea also cut rates that year. While monetary easing last year was due to a shift in focus to economic growth, what aided such rate cuts was benign inflation. Risks to inflation have, however, risen in recent months. Inflation is edging up in China and India, partly due to short-term supply constraints. A bigger risk to inflation though is any flareup in tensions in the Middle East, a major exporter of crude oil to Asia. On January 3, for example, the price of Brent crude went up by 3.4 percent due to rising tensions between Iran and the United States.17 Any escalation for an elongated period would push oil prices further up, thereby aiding consumer inflation in key crude importers in Asia. And if this is followed by a dent to currencies, imported inflation will likely go up. As of writing of this article, tensions appear to have eased for now and oil prices have receded.18

Consumers in Asia will be hoping that the risk of potential conflict in the Middle East reduces and that risks in the near term give way to more healthier prospects over the medium to long term. After all, they can draw comfort from expectations that economic growth in key economies in the region is expected to pick up in 2021–2024,19 with the uptick likely to gain momentum if current trade-related disagreements are resolved. That would aid gains in household income and wealth and will ensure that the legions of the middle class keep expanding.

Browse the Economics collection

-

Global Weekly Economic Update Article6 days ago

-

A view from London Article2 weeks ago

-

Japan economic outlook, October 2024 Article2 months ago

-

Canada Economic Outlook Article4 years ago

-

Monetary policy in emerging economies Article5 years ago