China Bracing for a slowdown

Notwithstanding expected growth deceleration, quality of growth could well be improved if policymakers took advantage of trade deal–induced liberalization measures by shifting the growth impetus to consumers.

The seemingly miraculous progress of trade talks between China and the United States is in line with our expectations (see our previous piece entitled More economic tensions and heightened uncertainty ahead of trade deal on Deloitte Insights).1 The United States will roll back some of its tariffs while China will execute its committed purchase of US products and further open up its domestic markets (mainly in financial services).2 Of course, there will be some uncertainty in 2020 because none of the thorny issues such as subsidies to state-owned enterprises or technology transfers have been dealt with in the so-called “phase one” trade deal. The reality is that both sides have become more realistic and this realism has paved the way to a trade deal. Nonetheless, China bashing is likely to resurface during the US presidential election 2020 as in the past.

Learn more

Explore the Economics Collection

Subscribe to receive related content

Download the Deloitte Insights and Dow Jones app

On the home front, China’s continued economic resilience in the face of a global slowdown and the protracted trade war with the United States clearly point toward the fact that its policy framework should focus on structural reforms or a faster pace of liberalization (in the financial sector in particular) and refrain from unleashing a large fiscal stimulus. This has been Deloitte’s position for some time now and the Q3 GDP growth of 6 percent has not shaken it. Unlike economies in crisis, China still has much policy leeway in the sense that certain reforms can be undertaken without sacrificing the growth target of around 6 percent. This seems to have been understood by policymakers, as not long ago the government announced its decision to do away with the foreign ownership ceiling of asset management companies.3 In the short run, we believe that the best policy response to the present situation would be continued implementation of measures to ensure better market access for both foreign companies and private enterprises. This will make further escalation of the ongoing US-China trade war difficult.

However, what the Q3 GDP growth rate figures have done is reignite the eternal debate on whether China’s policies should be more pro-growth or not. If economic deceleration continues, it is conceivable that the growth rate will dip below 6 percent in the coming quarters. But should this really be a cause for concern? The chief purpose of a GDP growth target is maintaining social stability. In China, social stability is all about job creation. At the height of the Asian financial crisis, premier Zhu Rongji had pledged to deliver 8 percent GDP growth. A widely accepted view then was that 1 percent GDP growth could be translated into 2 million jobs. But this kind of relationship between growth and employment no longer holds true, as in recent years the Chinese economy has undergone profound structural changes, with consumption playing an increasingly important role as a growth driver. The services sector now accounts for 46.3 percent of total employment, though it doesn’t necessarily contribute much to a high GDP growth rate.4

In most developed and some emerging markets, the Philips curve—a basic economic theory on the trade-off between inflation and the unemployment rate—is being challenged.5 Intuitively, a tight labor market should result in higher inflation, urging policymakers to respond with a tighter fiscal policy or raise interest rates or do both. But, today, the reality on the ground is that there are scant signs of inflation in the US economy and unemployment rates have hit an all-time low. But, far from raising interest rates, the US Federal Reserve is likely to cut interest rates twice in 2020 based on fears of a possible economic slowdown caused by the trade war. Would the frustrations faced by western central banks—the Fed, the European Central Bank (ECB), and the Bank of Japan (BOJ)—to reflate their economies justify a greater dose of fiscal stimulus in the west? The ECB is clearly moving in that direction with its continued quantitative easing (QE) which, if looked at closely, is really nothing less than a quasi-fiscal expansion. In China today, growth is decelerating while inflation is slowly creeping up (the September consumer price index exceeded 3 percent for the first time since November 2013, and the number reached 3.8 percent in October). Of course, this is mainly due to the surging pork prices caused by the African swine fever virus, which suggests that an overshooting of inflation remains unlikely in 2020. In the final analysis, with low interest rates in most economies, it is becoming tempting to resort to fiscal stimulus.

However, China’s situation is very different from most developed nations where growth is likely to be sluggish in 2020 (except for the United States). The floor for China’s economic growth rate is around 4 percent (largely due to confident consumers), assuming investment and trade do not make any contribution to GDP growth. Of course, the Chinese economy is unlikely to grow at a rate as low as 4 percent in 2020. Our baseline growth projection ranges between 5.5 percent and 6 percent in 2020, assuming there will be a moderate stimulus. This could come in the form of a mild adjustment of the RMB exchange rate—always a good option for boosting exports and enhancing the effectiveness of monetary policy. In developed countries, efforts are also being made to introduce measures that will have the effect of automatic stabilizers (e.g., unemployment benefits) kicking in when a downturn occurs. But in China, since policymakers can easily approve big projects with accommodative bank lending, there is always the risk of overdoing the fiscal stimulus as in late 2008.

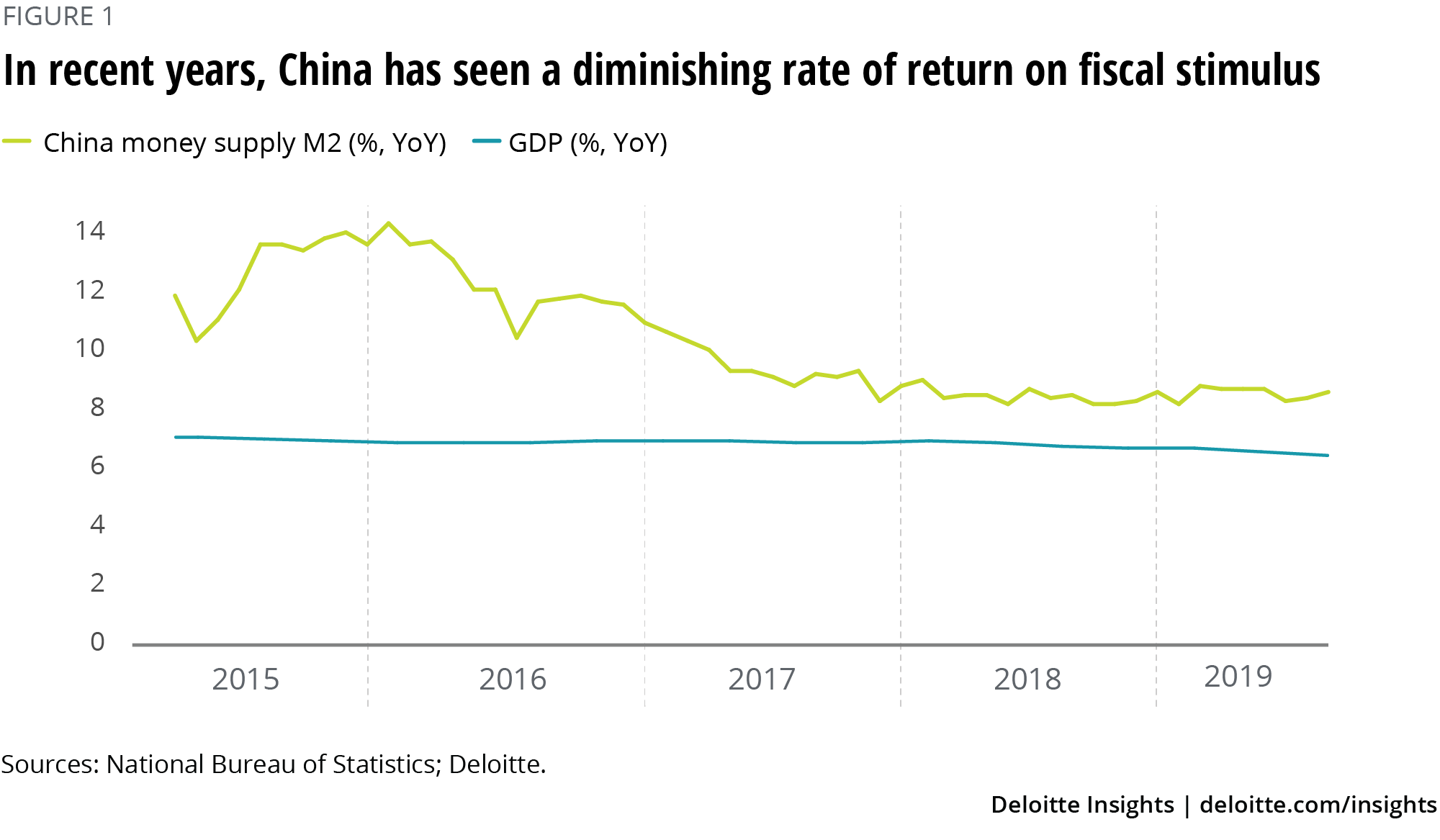

The main source of China’s economic slowdown is a legacy of past stimulus (leverage and excess capacities) as it has become abundantly clear in recent years that credit has a diminishing rate of return in terms of generating headline growth (figure 1).

Yet, in 2019, China has seen a policy U-turn on the de-leveraging campaign as official narratives have put “structural adjustment” on the backburner. Meanwhile, there has been greater emphasis on poverty reduction with a stated goal of realizing total “elimination of poverty” by 2020. In terms of policy implications, this means that China recognizes the need to achieve greater fairness—perhaps at the cost of bank asset quality. In our view, this is the right policy approach in light of the widening income disparity in China. The Gini coefficient for China has been creeping up since 2015 and reached a score of 0.468 in 2018; 0.4 is the warning level set by the United Nations. If de-leveraging continues to be put on the backburner in 2020—a plausible policy choice when corporate investment has been adversely affected by supply chain uncertainty even with the US-China truce in place—then it would be better for consumers rather than corporates to increase leverage and for zombie companies to be gradually weeded out (meaning there could be some reduction of excess capacity). The key question is whether consumers will remain confident in the face of a slowdown or the slide in the economic growth trajectory to 5–6 percent.

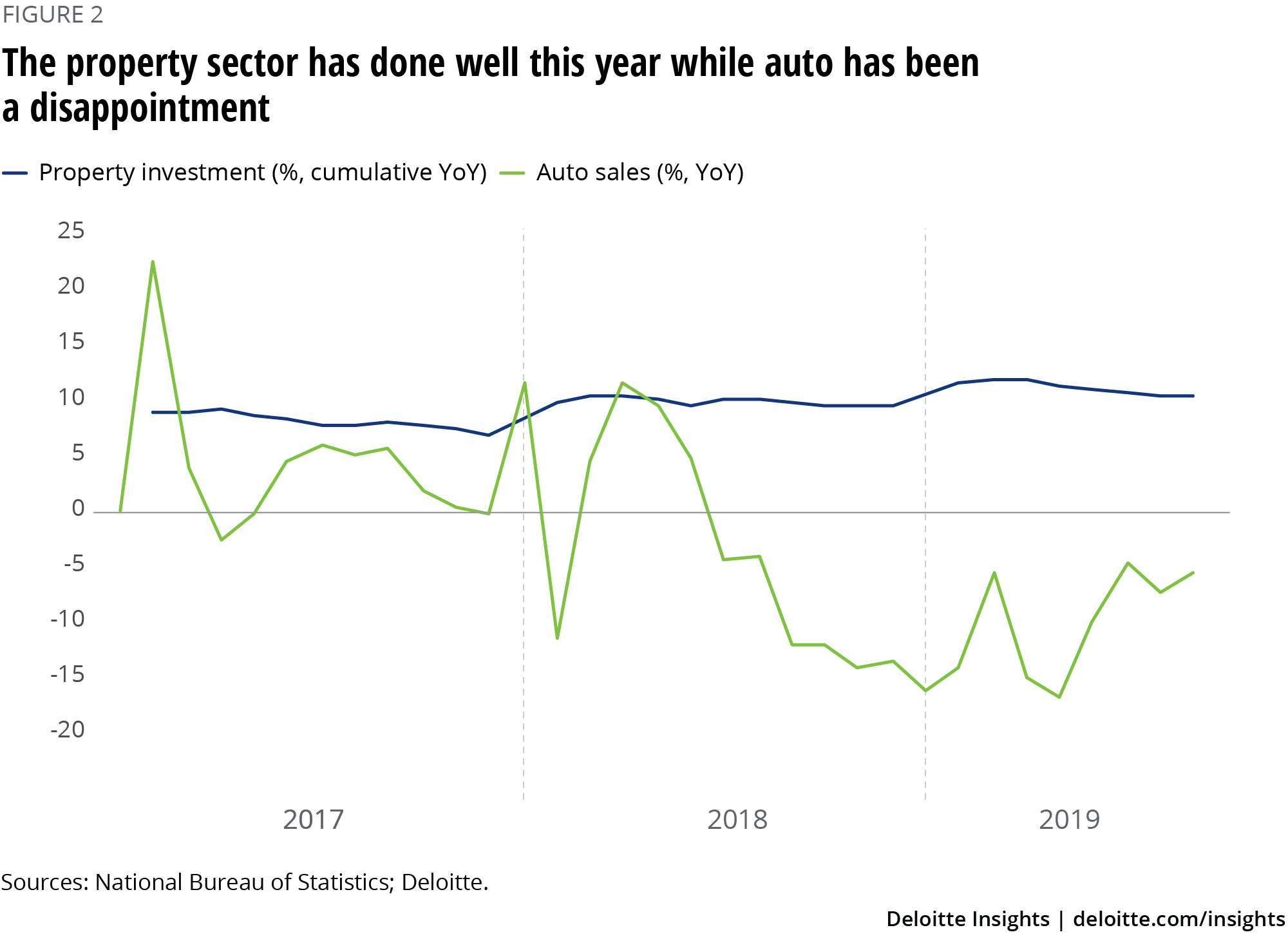

The answer to this lies in the housing market. So far in 2019, the real estate sector has performed better than most people expected (figure 2). Housing prices are stable in most cities while property investment is growing at around 8–9 percent. Why are developers stepping up their investments in the face of reduced expectations of asset inflation?

One plausible explanation is that the cost of financing is still fairly affordable. Though China has not joined the global monetary easing chorus, the People’s Bank of China (PBOC) has been using policy tools to improve liquidity and to guide interest rates down. In urban China, pent-up demand remains strong partly due to a cultural preference for homeownership and partly due to the absence of other sound investment vehicles. To spur growth, the government could simply relax restrictive policies on home purchases as China still has much room to increase urban populations.

In conclusion, the property sector has turned out to be the bright spot in an otherwise troubled 2019, while the auto sector has been a disappointment. We could argue that sluggish auto sales are a global phenomenon. But, from a car-ownership perspective, China is still an emerging market compared to countries with a comparable per capita income (e.g., Brazil and Malaysia). The phasing out of rebates and higher emission standards explain the drag on car purchases in China in the short run, but the convergence trend with countries such as Brazil in terms of car ownership, fuelled by underlying unfulfilled consumer demand, does suggest that China is far from being a mature car market and hence there is little real cause for concern.

To round up, we see slower growth in 2020 but we also see little need for China to embark upon major pump-priming. The uptick in inflation caused by the African swine disease is more than likely to be transitory. As such, a managed gentle slide of the RMB will be a better reflation tool provided China can significantly improve market access.

Explore more economics content

-

Global Weekly Economic Update Article2 days ago

-

Canada Economic Outlook Article4 years ago

-

Japan economic outlook, October 2024 Article2 months ago

-

Eurozone economic outlook, September 2024 Article3 months ago

-

India economic outlook, October 2024 Article1 month ago

-

A view from London Article4 days ago