The transportation agency of the future Managing mobility amid disruption and digitization

12 minute read

24 August 2020

As the new mobility ecosystem evolves amid turbulence, it’s up to transportation agencies to keep everyone on track. Can they keep pace with change?

Introduction

Much has changed since President Eisenhower signed the Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1956 authorizing the construction of 41,000 miles of interstate routes.1 Today, federal, state, and local transportation agencies manage an evolving infrastructure that is moving beyond roads, bridges, and tunnels to incorporate everything from multimodal mass transit to the first self-driving vehicles. The challenges these agencies face cross different transport modes and spheres of influence.

Learn more

Explore the Future of Mobility collection

Learn about Deloitte's services

Go straight to smart. Get the Deloitte Insights app

Today's era is one of unprecedented disruptive innovation in mobility. Many transportation agencies’ processes and procedures are rooted in the mid-20th century and could be ill-suited to today’s rapidly evolving landscape. In the last decade alone, the transportation ecosystem has expanded to include transportation network companies, ride-hailing, car-sharing, bike-sharing, micromobility, and microtransit, as well as digital trip planning, ticketing, and payment. At the same time, changes in commuting habits and demographic shifts are altering the economics of mass transit.

Traditional transportation agencies aren’t built for rapid innovation. Their typical decades-long planning cycles and procurement processes and workforce systems tend to be incompatible with many new approaches—and could hinder their ability to thrive in the future of mobility.

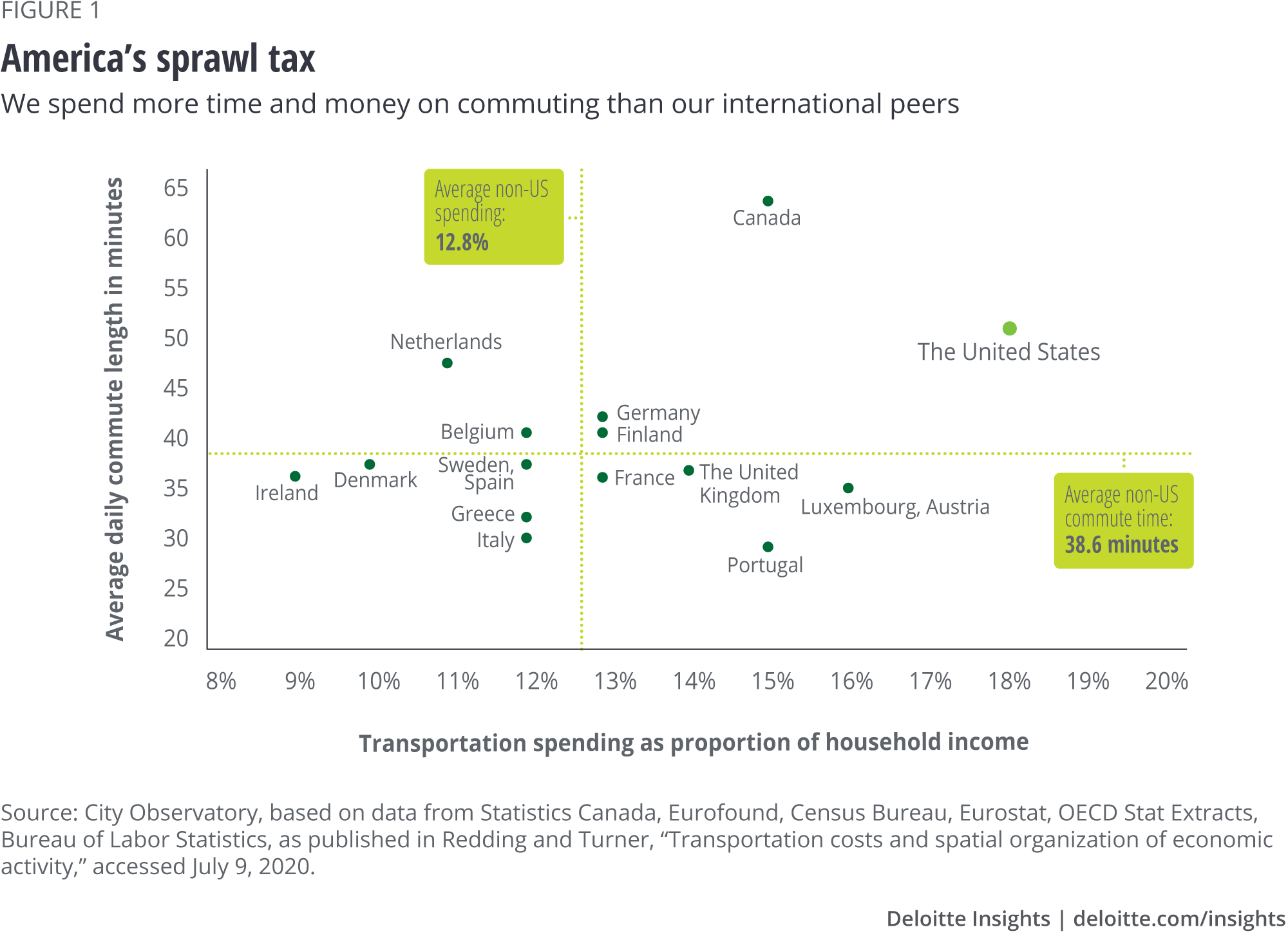

Transportation in America is at a crossroads. Americans waste more time in traffic than just about anyone on the planet (figure 1), and our existing infrastructure is crumbling, with an estimated US$836 billion backlog of highway and bridge projects, and another US$90 billion needed to bring our transit systems back to “a state of good repair.”2

The traffic burden on Americans highlights the strained environment within which our agencies operate. The lower land-use density than Europe requires a more expansive transportation infrastructure and reduces the efficiencies of scale upon which mass transit systems rely. COVID-19 has only added to the financial pressures on US transportation planners; revenues from user fees, sales taxes, and motor fuel taxes are expected to decline by an average of 30% through 2021, while lockdowns and “shelter in place” have slashed mass transit ridership.3

For transportation agencies, the most important change may involve mindset: a shift from a perspective focused on individual missions to one focused on the entire mobility ecosystem.

This article examines the fundamental forces of change shaping the future of transportation and, more importantly, suggests measures officials should consider as they attempt to create more resilient, adaptable, and innovative organizations. The most important change needed may involve mindset—the shift from a perspective focused on individual agency missions to one focused on the entire mobility ecosystem, in which public and private stakeholders coordinate to achieve better outcomes for all. For many agencies, such a shift will demand a deep cultural change—and one that should start at the top of the organization.

What disruptions are expected to affect transportation agencies?

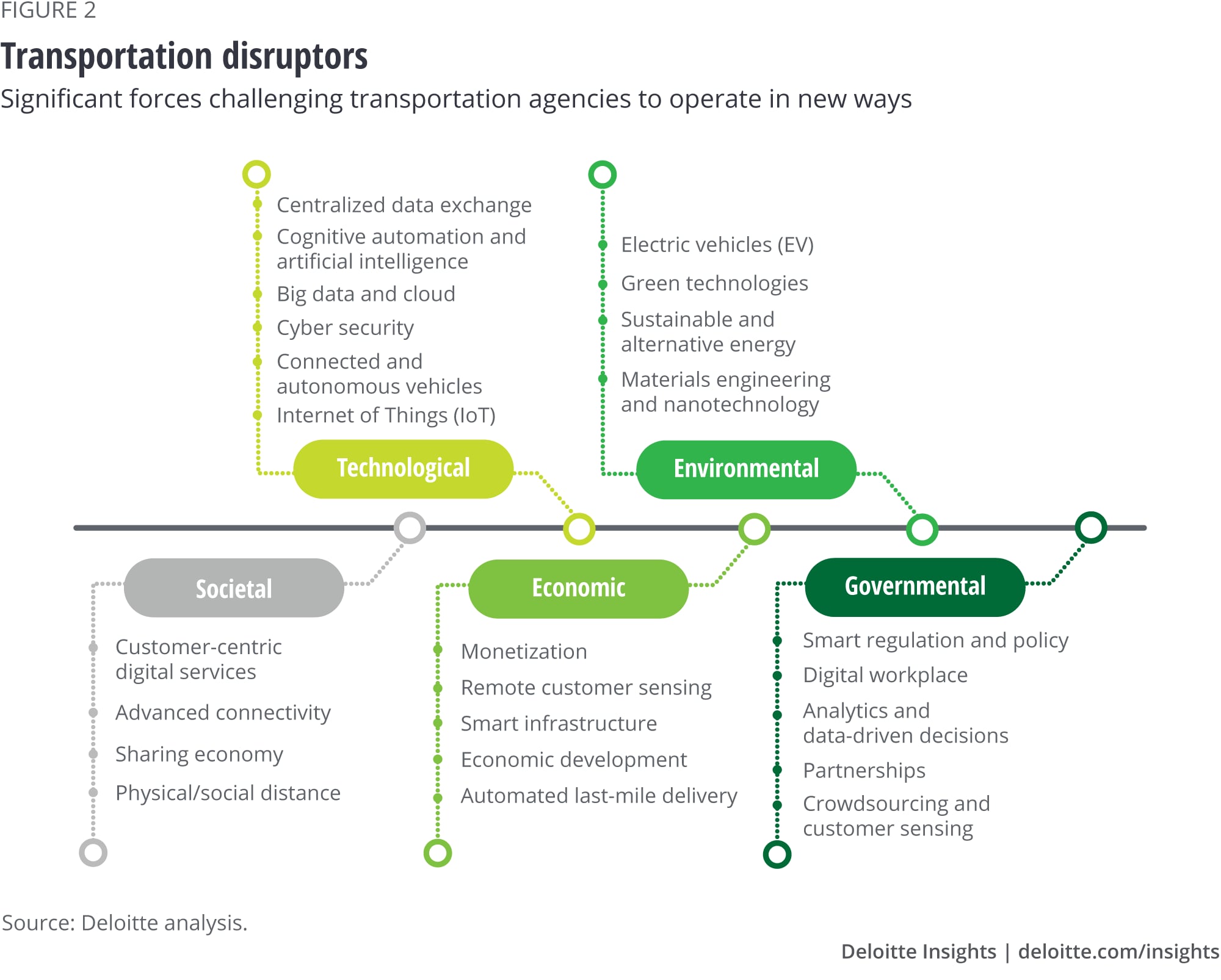

A wave of disruptions is likely to shape the future of American mobility, dramatically shifting agency priorities, business operations, and relationships with key stakeholders. We classify these disruptions into five broad categories: societal, technological, economic, environmental, and governmental (figure 2).

Agencies will feel the impacts in different degrees and on different timelines, depending on geography, traveler demographics, funding sources, and other factors.4 But every agency will likely have to grapple with these forces eventually; those who begin to adapt now could be better positioned to shape—rather than react to—the evolving mobility ecosystem.

Societal trends include shifting demographics and changing attitudes about the use of transportation. User preferences can shift quickly, but it can take years for infrastructure to catch up. Ongoing urbanization, for instance, is lowering the general demand for personal car usage. According to the US Department of Transportation, millennials were driving 20% fewer miles by the end of the 2000s than at the start of the decade, while options such as ride-hailing and e-scooters were becoming increasingly popular.5 The rise of these digitally enabled services has pushed up expectations as well. Consumers want transportation options that provide the same level of availability and dependability they experience in other parts of their daily lives.6

Some transportation agencies are beginning to respond, placing more emphasis on customer experience and addressing long wait times and limited hours through a mix of technology and process changes.7 In all, transportation agencies should continuously reassess their priorities to ensure that the services they offer match society’s shifting preferences.8

Technological trends are perhaps the least predictable, yet they affect both mission execution and the shape of the broader mobility landscape. On-demand shared mobility has become a fixture and electric vehicles are more common, with profound implications for motor fuel taxes. Connected vehicles are increasingly commonplace, and autonomous and unmanned aerial vehicles are in development. Some transportation agencies already employ IoT networks and sensors that provide real-time data on street-level activity; they’ll face challenges in upgrading legacy systems and abilities to take advantage of the latest digital technologies, from cloud computing to advanced analytics.9

Transportation agencies should be able to sense and respond to innovation, and be open to solutions that harness data and technology to tackle old and new challenges. Market spending on technology such as smart parking products, which allow parking operators to remotely monitor parking occupancy rates in real time, has risen in the last few years. By the end of 2018, 11% of global public parking spaces had become “smart,” a share projected to rise to 16% by 2023.10

Economic trends challenge strategic priorities and expand the universe of stakeholders. As costs rise, infrastructure ages, and traditional revenue sources decline, agencies should be prepared to expand their use of public-private partnerships and new revenue-generating options to bridge the widening funding gap. Traditional sources of transportation revenue, such as motor fuel taxes and vehicle registration fees, are declining, and the pandemic’s economic fallout will likely only exacerbate these trends.11 California, for example, may lose US$1.3 billion in motor fuel tax revenue as a side effect of COVID-19.12 Public transit is in an equally challenging position—LA Metro expects to lose US$1.8 billion through June 2021.13

In response, most agencies are exploring alternative revenue streams such as congestion fees, mileage-based user fees, carbon taxes, and data monetization.14 Many already employ public-private partnerships to deliver and finance transportation projects.

Environmental trends are driving expectations that transportation systems should reduce pollution and other negative effects. Transportation agencies are asked to mitigate emissions, reduce single-occupancy vehicle usage, and adapt their infrastructure to the effects of climate change.

Regulations can unlock new ways of thinking. In December 2018, for instance, California adopted legislation that changed the way its agencies evaluate transportation impacts by requiring agencies to look at vehicle miles traveled (VMT) with the goal of better measuring the actual transportation-related environmental impacts of any given project. Transportation agencies across California are changing their processes to comply with the new California Environmental Quality Act, considering new demand management techniques and incentive programs for shared mobility.15

Governmental trends involve the evolution of agency priorities, expectations, and workforce needs. Governments increasingly use technology to increase civic participation and leverage decentralized expertise for the reinvention of core services.16 In the near term, agencies can implement crowdsourcing and behavioral economics (“nudging”) to assess and capture generational preferences and perceptions. Over time, transportation agencies should consider investing in smart regulation and policy responses that keep pace with industry innovations. Internal stakeholder engagement and training could play a critical role in furthering the awareness and adoption of these innovations and associated policies.

Transportation agencies should consider these disruptive trends as opportunities to advance new solutions. Agencies have the chance—starting today—to lead proactively, plan effectively, and shape real-world outcomes.

Preparing for the future

Transportation agencies face an unenviable task. Even as they focus on maintaining critical infrastructure, expanding service, and guaranteeing safety, they must move—with urgency—to address emerging disruptions to the mobility ecosystem. But where to begin? Addressing new needs could call for innovative and continuous transformation.

Strategic vision and challenges

Effective change often begins with embracing a new vision, in which transportation agencies can:

- Act as conveners of the mobility ecosystem

- Find innovative solutions to connect rural and urban areas

- Develop smart infrastructure

- Evolve new public-private partnerships

- Pilot and deploy new modes of transport and related technologies

An early glimpse into such a vision comes from Southern California, where the San Diego Association of Governments is laying the foundation for a complete overhaul of the region’s transportation system. Its goal is to make the system more sustainable, accessible, affordable, and safe, while providing viable alternatives to trips made in single-occupancy vehicles.17

Such transformations, as we’ve noted, will likely require a fundamental shift in mindset as well as investments in the resources, processes, and systems needed to anticipate and tackle disruptive trends. For instance, the steep decline in transportation revenue due to the pandemic is drastically affecting agencies across the nation—and will require transportation officials to meet changing stakeholder expectations and heightened health and safety considerations with limited funding.18 Transportation policy and planning should be remade by focusing on the data, technology, and human capabilities needed to adapt to an increasingly digital world.

An agency’s effectiveness in integrating new and traditional services can transform its role from bystander to catalyst for the mobility ecosystem of the future.

The path forward

The new vision should anchor the path forward as transportation agencies work toward an integrated, frictionless transportation system. Agencies should align this clear vision of the future with their business operations and workforce capabilities, using data-driven decision-making, agile approaches to problem-solving, customer centricity, and a laser focus on outcomes.

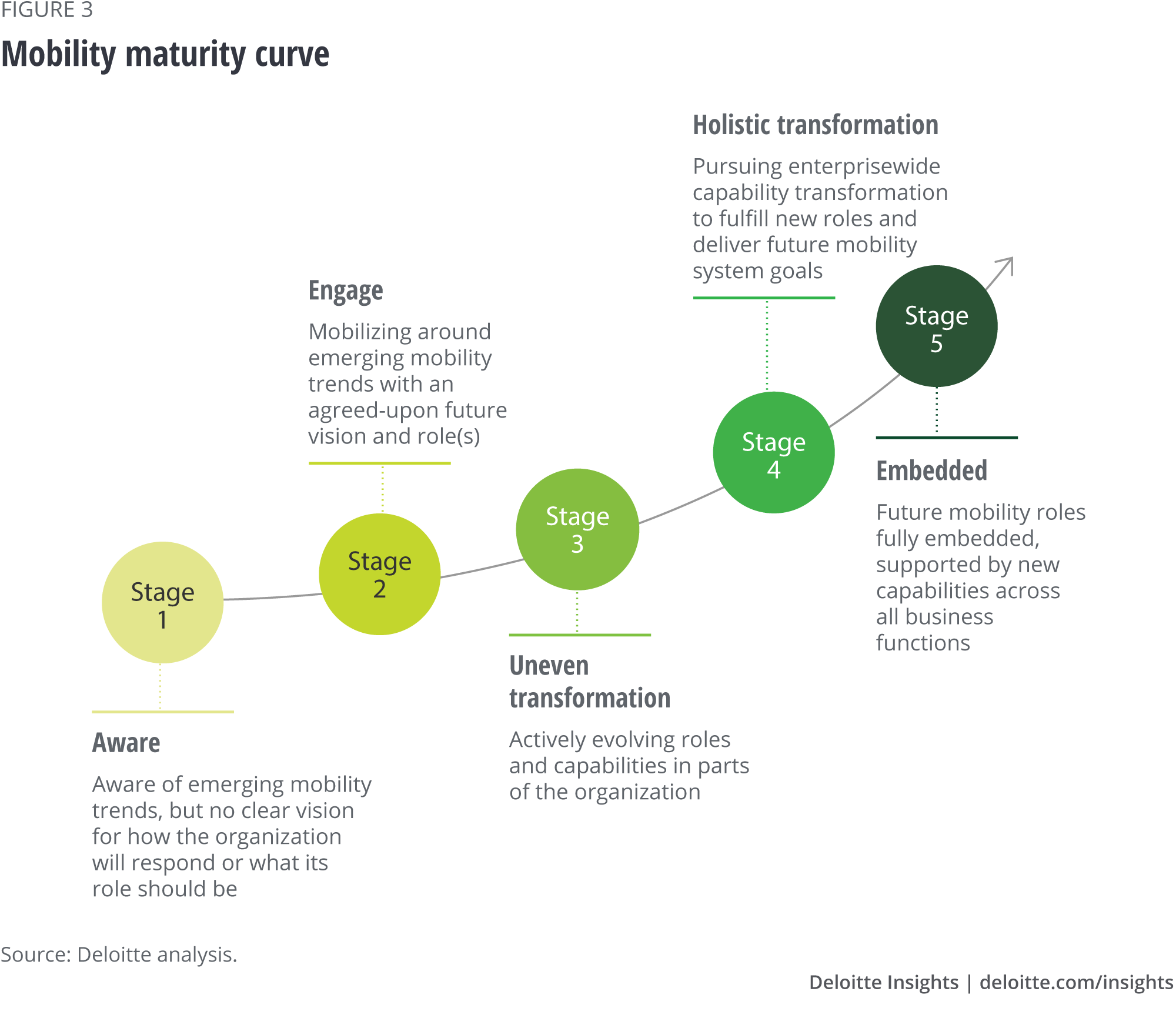

The mobility maturity curve (figure 3) can help agencies gauge their preparedness for the new mobility ecosystem and the extent to which their current decision-making reflects changing requirements.19

The curve has five stages, from aware (Stage 1) to embedded (Stage 5). Aware describes an organization at the start of its journey: determined to make the transition but lacking dedicated resources, strategies, or metrics to shape its response. At the other end of the curve, these abilities are embedded at the heart of the agency’s policy and operations.

Actions for tomorrow

As noted above, societal, technological, environmental, economic, and governmental disruptors can and will change transportation’s role in society dramatically. Already, the COVID-19 crisis has compelled travelers to rethink mass-transit options, accelerated telework, and realigned domestic supply chains.20

In the new era, transportation agencies should let data guide their decision-making to make the most of scarce resources. They should act in concert with all mobility ecosystem stakeholders and ask hard questions about the future of their organizations. Agencies can focus their efforts to prepare for a disrupted future by focusing on five specific areas of transformation.

Building the future workforce

As agencies prepare for a more collaborative and technologically advanced role, they should consider what the transition means for employees at all levels. While technology has tremendous potential, realizing its benefits often depends heavily on employee skills.

For every new and legacy work activity, employers should reevaluate which tasks can be contracted, what work can be done remotely, and what work may turn out to be unnecessary. The pandemic has accelerated this dynamic. The nature of work, workforce, and workplace is changing, and agencies should consider the implications of each to succeed.

Convening public and private stakeholders

Transportation agencies can play a natural leadership role in convening stakeholders to devise collaborative and inclusive mobility policies and outcomes. Major employers, economic development corporations, academia, nonprofits, and even public health advocates recognize the ability of smart transportation investments to catalyze further investment and attract skilled workers. At present, however, many new transportation companies and providers of micromobility solutions such as electric scooters are rushing to bridge gaps in mobility access.

For example, Los Angeles recently launched the Urban Movement Labs, a public-private coalition to drive innovation in transportation. The coalition includes the Mayor’s Office of Economic Development, the City of Los Angeles Department of Transportation, Los Angeles World Airports, the Port of Los Angeles, and private partners including Lyft, Waymo, and Verizon. In partnering with the nonprofit world, academia, and users, the coalition plans to develop solutions for the city’s daily transportation challenges and pilot them within the city.

Mastering data analytics and data-driven decisions

The COVID-19 pandemic has triggered major funding shortfalls due to reductions in user fees, motor fuel taxes, toll charges, and transit farebox receipts. In such an environment, officials should assess investments and benefits for every dollar used to plan, design, build, operate, and maintain transportation systems. Data analysis can be used to expose inefficient processes, monitor project performance, estimate revenues, and fully understand safety considerations, enhancing agencies’ ability to get the most from scarce resources and deliver the best outcomes for key stakeholders.

Pittsburgh, for instance, has experimented with an AI-driven traffic light system that adapts to current conditions instead of a preprogrammed pattern. By building a predictive system using computer vision and radar technology, the city can modify its traffic signaling patterns in real time. The system has helped reduce travel times by 25%, braking by 30%, and idling by more than 40%. Other cities and states are using detection systems that employ infrared cameras and other vision technologies to catch drivers who use restricted lanes illegally.

Accelerating novel technologies

The last decade has seen a wave of disruptive transportation technologies; local governments were caught flat-footed when ride-sharing services arrived unannounced and, again, when shared mobility companies started dropping scooters and dockless bicycles on city streets. Another wave of innovations—from electric, connected, and autonomous vehicles to hyperloops and urban air mobility—may transform transportation yet again.

By partnering with innovators and disruptors, agencies can offer a regulatory structure and advocacy for the orderly introduction and accelerated adoption of these novel technologies. Proactive partnerships can bring new technologies to key stakeholders while ensuring equity in implementation.

Consider Suntrax, the facility developed by the Florida Department of Transportation’s Florida’s Turnpike Enterprise unit to test tolling technologies. In 2021, the facility will expand to support autonomous vehicle (AV) and connected vehicle (CV) tests on a 2.2-mile-long test track. Suntrax also includes a 200-acre facility to test AV technologies in highway, high-speed, and urban settings. Similarly, the Texas Innovation Alliance provides controlled testing facilities for AV technology in Austin, Houston, Dallas, Fort Worth, San Antonio, and El Paso. And Ohio is already home to the largest contained testing site for AV and CV technologies, the SMARTCenter; DriveOhio, a collaboration between Ohio’s Department of Transportation and academic partners, plans to launch a pilot for rural AV testing.21

Using simulation-based planning for smarter portfolio management

Economic forecasts and legacy modeling techniques have long driven transportation project planning and policy design. But recent advancements in digital simulation now allow such agencies to create a virtual landscape populated with AI agents whose behavior reflects that of actual travelers, in a fraction of the time needed for older modeling.

By modeling the behavior of individuals at scale, digital twins can simulate vehicle miles traveled, greenhouse gases, revenue, and other impacts of transportation policies and projects with unprecedented granularity and scope. They can provide planners with vastly improved abilities to create new transportation options and improve returns on investments.

Airservices Australia, for instance, is exploring how digital simulation can be combined with IoT and machine learning to enhance its ability to manage air traffic. It has developed a digital twin of Airservices’ air traffic network using historic air traffic data, and intends to use it to optimize flight routes and test strategies for dealing with disruptive innovation. Strategists are expected to be able to test a wide range of scenarios for managing the multidimensional airspace of the future.22

Conclusion: A transformed transportation agency for a transformed mobility landscape

The most forward-looking transportation agencies can use these new technologies and methods to transform their operations, positioning themselves to make better decisions grounded in data, work more flexibly and proactively, and become champions for technological innovation—and the people they serve.

© 2021. See Terms of Use for more information.

More in Future of Mobility

-

Electric vehicles Article4 years ago

-

Software is transforming the automotive world Article4 years ago

-

Location, location, location in a mobile future Article5 years ago

-

Regulating the future of mobility Article6 years ago

-

Picturing how advanced technologies are reshaping mobility Article6 years ago