Location, location, location in a mobile future Residential, retail, and health care real estate in the new mobility ecosystem

9 minute read

10 January 2020

The new mobility ecosystem involves transporting people and goods from point A to point B in different ways. And that means profound impacts on the uses—and value—of real estate: points A, B, and everything in between.

In the century since the automobile began to change America’s mobility landscape, urban planning and real estate development have centered around the car. For decades, an auto-dominated culture has shaped how people get to work, how they shop, and where they live, which in turn determined the design, location, and value of real estate developments.

Learn more

Explore the Future of mobility collection

Subscribe to receive related content

Download the Deloitte Insights and Dow Jones app

But in recent years, the mobility landscape has seen important changes. In 2018, more than a third of American adults used ride-hailing services—an industry that scarcely existed less than a decade ago.1 By 2040, shared autonomous vehicles could account for more than half of road miles in the United States.2 These shifts in transporting people and goods from point A to point B imply profound impacts on the uses—and value—of real estate: points A, B, and everything in between.

This introductory article touches on some of the challenges and opportunities that the new mobility ecosystem poses for three components of the real estate industry: the residential, commercial retail, and health care sectors. For investors and developers, the changing demands and use of real estate could have significant impacts on the potential risks and returns of property portfolios, design decisions for new developments, and the redesign and maintenance of existing establishments. Understanding and taking into consideration mobility trends will likely be imperative to the long-term returns of today’s real estate investment decisions.

The future of mobility

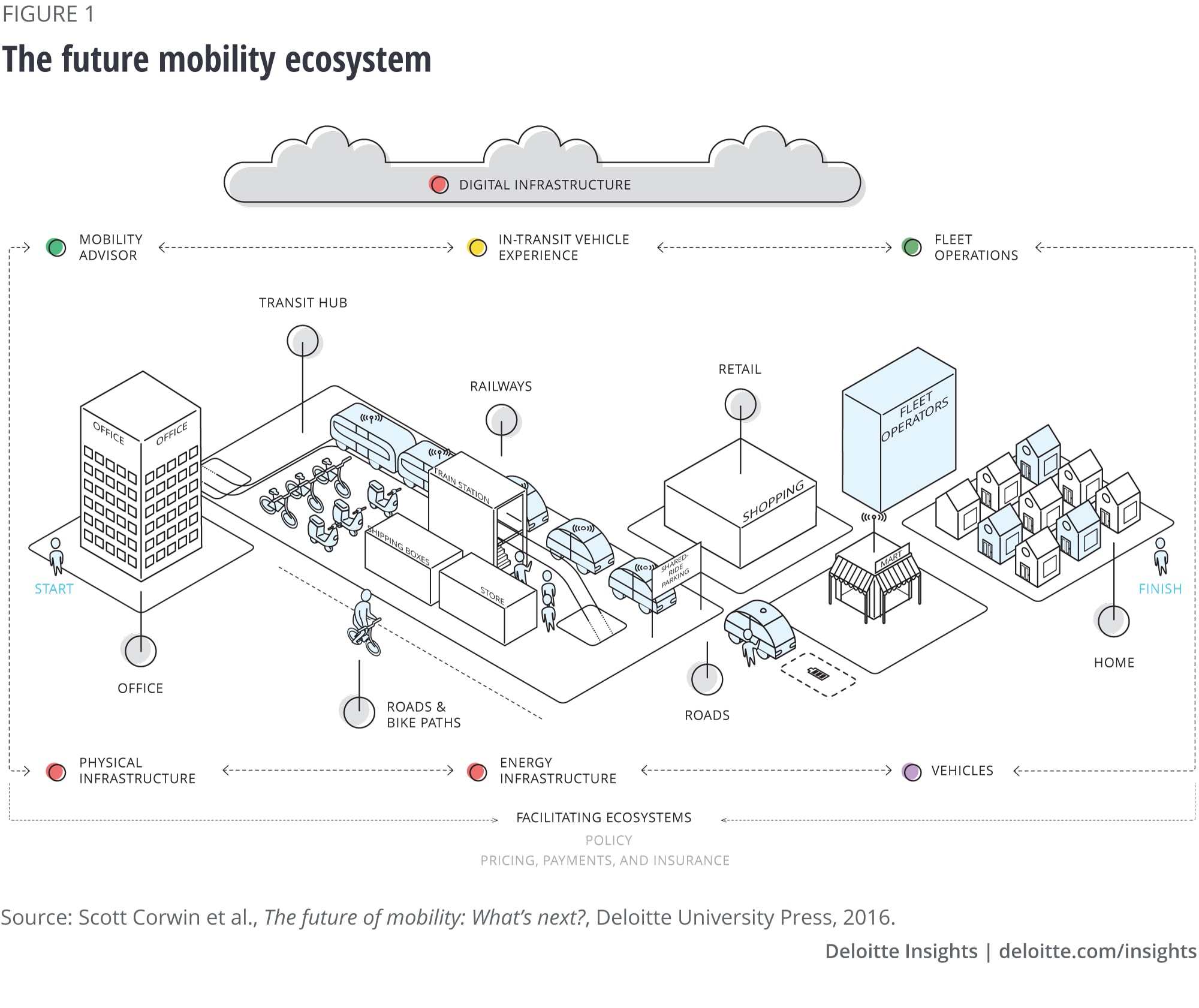

A series of converging technological and social forces, including the emergence of connected, electric, and autonomous vehicles and shifting attitudes toward mobility, are beginning to profoundly change the way people and goods move about. Already, we are seeing the emergence of a new mobility ecosystem that can enable seamless, intermodal transportation that could be faster, cheaper, cleaner, safer, more equitable, and more accessible than today (figure 1).

While much remains uncertain,3 the widespread adoption of integrated multimodal transportation, shared mobility services, and ultimately autonomous vehicles is likely to shift land use demands and lead to new patterns of behavior for consumers. Of course, the trajectory of the real estate market will likely be shaped not only by shifts in mobility but by population movements and urbanization, demographic shifts, zoning and other broader regulatory changes, and the condition of the overall economy.

Real estate impacts

Residential

While the net changes are difficult to predict, one impact of mobility trends is the likely acceleration of the gentrification already occurring in many urban areas. Decommissioned parking spaces can be repurposed to create new green spaces, wider sidewalks, dedicated bike/scooter lanes, or residential developments, increasing the allure for residents. The growing availability of micromobility services, such as e-scooters and shared bikes, can reduce car traffic, creating public spaces that are more enjoyable for all users. Coupled with a shift toward electric vehicles, air quality could improve and road noise might fall. Collectively, safer, quieter, and more walkable neighborhoods—all connected by an intermodal web of convenient, on-demand transportation options—could further increase the appeal of city living.4

Still, potentially the largest upward pricing pressure from future mobility trends could be felt in exurban communities that are far from the urban core and characterized by large amounts of relatively cheap land.5 Such towns, especially those anchored by at least one walkable lifestyle center with retail and dining, could be poised to attract wealthier families and retirees seeking to separate their day-to-day life from the city center, while still enjoying ready access to its amenities—a type of mixed-use development (see sidebar, “Rethinking transit-oriented development”).6

Rethinking transit-oriented development

For those who cannot or choose not to live in the urban core, suburban transit-oriented developments (TODs), anchoring community centers, could offer an attractive way to remain connected to a city while maintaining a different home life.

The Transit Oriented Development Institute defines a TOD as a development located within a certain distance (typically a half-mile, or a 10-minute walk) from a public transportation center.7 Developers can find TODs attractive for many reasons, including community-provided financial or other incentives, increased development density, reduced parking requirements, and the premiums that are attainable for residential units due to its desirable location. Well-defined TOD areas can also enable more efficient mobility offerings tailored to the area, for both people and goods.

New mobility services—including (ultimately autonomous) ride-hailing, e-scooters, and bikeshare programs—have the potential to increase demand for housing beyond a TOD’s defined boundaries. Similarly, seamless intermodal mobility that connects to public transit could lessen the effect of the first-mile/last-mile problem,8 increasing the value of residential real estate outside of a TOD area as currently structured. This could prompt cities to rezone for larger TOD developments, making land within a wider radius from the transit center more attractive for development.

Many of the collaborations and new services to extend the reach of public transportation have already begun. To encourage mass transit use in the age of ridesharing, several municipalities have entered into partnerships with major industry players. Some ride-hailing and microtransit companies have inked partnerships with local authorities to integrate public transportation information within their apps and to encourage the use of mass transit by offering discounted rides to transportation centers.9 Nearly half of the shared bike trips in many Chinese cities are part of a multimodal journey that includes public transit.10

Retail

Like residential properties, the major trends unfolding in mobility are expected to impact commercial real estate through its effect on physical store layouts, parking needs and configurations, and the consumer shopping experience. As retailers embrace digital technologies, from the warehouse to the point of sale, physical store layouts will likely also need to adapt to increasing demands for efficiency and consumer convenience. This could be especially true for grocery and convenience stores as they shift toward e-commerce and increasingly experiment with autonomous vehicle (AV) delivery programs. For example, one of the largest US supermarket chains has successfully concluded an AV same-day delivery service pilot program in Scottsdale, Arizona, and is now expanding this service to customers in the Houston area.11 Similar pilot programs are taking place across the country, such as in Oklahoma City, where AVs are delivering groceries to underserved communities and have the potential to expand to pharmaceutical and other merchant delivery programs.12 While still facing significant regulatory and technological hurdles, drones could expand the speed and reach of stores’ delivery efforts.

As new delivery systems continue to expand, many grocery and convenience stores are expected to reallocate space toward logistics and warehousing operations as they shift toward catering less to the in-person shopper.13 Changes to store layouts could include decreased square footage dedicated to retail shelving, increased back-of-store warehousing facilities to accommodate more spacing for goods, and automated processes for packing and distributing items; some of those changes are already underway. The grocery store of the future may increasingly resemble an Amazon fulfillment center, with robots carrying up to 750 pounds of goods and only one minute of human labor required to load a vehicle.14

Ultimately, real estate investors should consider the flexibility of existing retail real estate assets. Grocery and convenience retailers will need to adapt physical store layouts quickly and efficiently to accommodate the growing proliferation and sophistication of AV delivery systems. Existing facilities with ample utilities that are situated in locations with favorable road access, the necessary infrastructure to support AV, or other emerging delivery systems will likely offer attractive investment opportunities.

Health care

The health care industry is undergoing massive changes, as cost pressures and government regulations continue to force providers and payers to innovate and identify new models to serve patients. Shifts in mobility could improve access to health care for certain segments of the US population and change the way care is accessed for many more.15 This is especially true for the senior population, which is already expected to double from 2012 to 2050 as baby boomers age.16 As real estate developers, as well as owners and operators of senior homes, plan land purchases and forecast future revenues, they should consider how both health care and the future of mobility could affect their business.

Mobility is growing less and less dependent on the ability to drive. As autonomous driving becomes more accessible, seniors would be more easily able to visit friends and loved ones and participate in other social activities, potentially reducing their isolation. Today, more than half of nondrivers over the age of 65 do not leave home most days, partly because of a lack of transportation options.17 Autonomous driving could also make the delivery of goods and services, especially health care services, to seniors’ homes much more economical. The biggest reason most seniors move to elder housing is the ready access to health care. However, as new mobility technologies drive down the cost of transport and cost pressures continue to mount for traditional in-patient settings, many providers are developing home care capabilities. Drones are already being tested to deliver blood samples and other medical supplies.18 With more options to receive care in their houses, many seniors could delay their move to senior homes or shift toward mixed-use “55+ communities” being built near family-oriented TOD areas, enabling convenient access to loved ones.

To stimulate growth and mitigate the negative effects of new mobility options, senior living facilities and real estate operators would need to adjust their service mix to cater to the tastes of the increasingly independent baby boomers. For the increasing number of seniors who remain healthy enough to stay in their homes, senior living facilities can invest in creating more social programming such as fine arts, classes, and hobbies. The traditional business model that focuses on the number of beds would need to be adjusted to include more large spaces such as gyms and meeting rooms. Mixed-use 55+ communities that cater to this aging demographic and their new mobility options could also see strong demand.

An emerging opportunity: Living mobility labs

As new mobility technologies and services mature from prototypes to in-market applications at increasing scale, there is expected to be a growing need for physical spaces to serve as integrated, real-world test beds. In Toronto, Sidewalk Labs has proposed redeveloping the Quayside area with a strong focus on new approaches to mobility.19 Babcock Ranch, an 18,000-acre development in Florida, has piloted electric, autonomous shuttles.20 AllianceTexas, a 26,000-acre master-planned property owned by Hillwood Properties, recently launched a mobility innovation zone21 to capitalize on its array of logistics and transportation-focused infrastructure, including an industrial airport, an intermodal rail hub, and multiple distribution centers, and will host some of the first “flying taxi” efforts using electric vertical takeoff and landing aircraft.22

To capitalize on this trend in the near term, real estate developers and investors should look for properties with distinctive sets of assets that can enable mobility innovators to prove out their technologies and business models—and then actively market those places to the broader mobility ecosystem. They should also be careful to build in flexibility. Off-street autonomous vehicle test tracks, for example, are in demand today, but those vehicles could quickly move to public roads as the technology matures.

Conclusion

As mobility undergoes fundamental changes over the coming decades, investors and developers of real estate will likely be presented with unprecedented challenges accompanied by tremendous opportunities. This article only scratches the surface of the complex interactions between how we move and the spaces we occupy. To thrive in this changing landscape, real estate investors, developers, and operators may need to redesign and refocus their investments to adapt to the shifting travel behavior of consumers and businesses.

More from the Future of Mobility collection

-

Toward a mobility operating system Article5 years ago

-

The elevated future of mobility Article5 years ago

-

Infrastructure barriers to the elevated future of mobility Article5 years ago

-

Making micromobility work for citizens, cities, and service providers Article6 years ago

-

Technological barriers to the elevated future of mobility Article6 years ago