Diving deeper Five workforce trends to watch in 2021

Explore five workforce trends that show how organizations can bring out the human strengths that make organizational thriving possible.

Designing work for well-being

The end of work/life balance

Co-authored by Jen Fisher, Deloitte US chief well-being officer

While executives have long recognized that well-being is important, the COVID-19 pandemic brought home how significant it really is. Organizations suddenly found themselves called upon to prioritize workers’ physical and mental well-being as a matter of survival, as protecting their health and alleviating their stress became critical to operations. Work and life, health, safety, and well-being became inseparable. Recognizing the inextricable link among our well-being, our work, and our lives has led more organizations to think deeply about ways they can design well-being into work itself so that both workers and the organization can thrive moving forward.

Shifting realities

Well-being was rising on the organizational agenda even before the COVID-19 pandemic. In fact, well-being was the top-ranked trend for importance in our 2020 Deloitte Global Human Capital Trends study, with 80% of our nearly 9,000 survey respondents identifying it as important or very important to their organization’s success. Against that backdrop, when COVID-19 took hold, the crisis cast new light on the importance of well-being and made us acutely aware of the consequences when well-being is put at risk. Organizations took quick action to redirect resources towards making work safe and keeping workers healthy: moving workers into remote work arrangements, implementing testing and contact tracing strategies for onsite workers, and establishing new programs for emergency medical leave, childcare and eldercare support, and physical, mental, and financial health.

Learn more

Explore the 2021 Human Capital Trends collection

Revisit the 2020 Human Capital Trends

Order a copy of Work Disrupted, Deloitte’s new book on the accelerated future of work

Explore five characteristics of a resilient organization

Explore The future of work in a post-pandemic world

Vist our Dbriefs webcast on-demand

Learn about Deloitte's services

Go straight to smart. Get the Deloitte Insights app

As the pandemic went on, well-being remained paramount in organizational leaders’ minds. Conversations about the toll of social isolation and economic recession on workers’ mental and emotional health entered the public dialogue, and keeping workers physically healthy and safe continued to be a top priority. Some organizations took extraordinary measures to safeguard worker well-being: Delta Air Lines, for example, allowed 5,000 workers at higher risk for COVID-19 to stay at home during the pandemic, with full pay and medical benefits.1

In August 2020, Jen Fisher, Deloitte US’s chief well-being officer, posted a LinkedIn message that asked leaders to share the strategies and practices they were piloting to influence well-being in their organizations. The post, which garnered more than 500 reactions and 200 comments in a few days, revealed an expanding organizational focus on well-being. Leaders of organizations large and small said that they were tailoring their well-being efforts to various worker segments’ needs instead of taking a one-size-fits-all approach; finding new ways to allow workers to disconnect and recharge organization-wide; and focusing on equipping workers with the mental, emotional, and social skills needed to not just cope, but adapt and thrive.

What was most exciting to us in the reactions to Fisher’s post, however, were the examples of organizations designing well-being into work itself. We heard from organizations that were complementing well-being programs adjacent to work with efforts to embed well-being into the work. Some organizations were focusing on building digital wellness and productivity, while others were managing capacity at both the individual and team levels, and still others were encouraging job crafting—giving individuals autonomy to make meaningful decisions about what and how they contribute to the organization. One example of such actions is Starbucks’ approach to designing its partners’ (baristas’) work: A partner can expect their work schedule to be posted two weeks in advance, and if a partner has more than an hour-long commute, Starbucks works to transfer them to a closer store.2

Our 2021 perspective

Our hypothesis

COVID-19 has reminded us of the dual imperatives of worker well-being and work transformation, but executives are still missing the importance of connecting the two. Organizations that integrate well-being into the design of work at the individual, team, and organizational levels will build a sustainable future where workers can feel and perform at their best.

Seven in 10 executives responding to the 2021 Deloitte Global Human Capital Trends survey told us that their organization’s shift to remote work had a positive impact on well-being. However, the sustainability of remote ways of working continues to come into question as many parts of the world faced a second wave of COVID-19–related lockdowns.

The importance of work design in supporting remote work arrangements going forward has come to the fore at many organizations. When we asked surveyed executives what factors were most important to sustaining remote work, they overwhelmingly chose options related to the design of work (figure 1). Programs adjacent to work, such as enhanced corporate benefits and new well-being resources, fell to the back of the list as executives prioritized actions such as providing digital collaboration platforms, enabling worker choice, and changing scheduling and meeting norms, all of which directly embed well-being into the way work gets done.

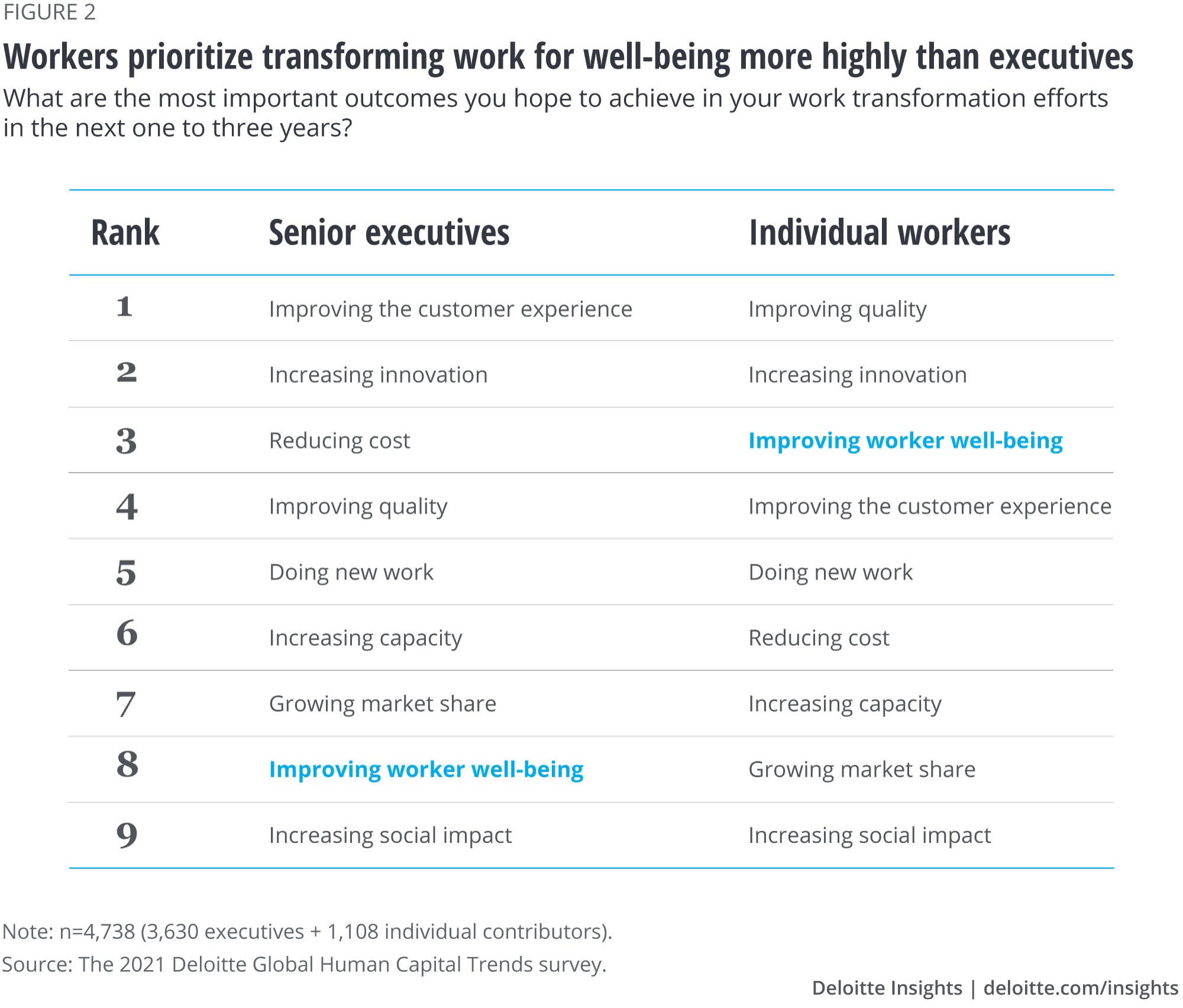

That said, we also found a continuing disconnect between employers and workers when it comes to prioritizing well-being in work transformation efforts. We asked both senior business and HR executives and individual workers to answer the same question: “What are the most important outcomes you hope to achieve in your work transformation efforts in the next one to three years?” Workers told us that the top three objectives of work transformation should be improving quality, increasing innovation, and improving worker well-being (figure 2). But improving well-being was the second-to-last outcome identified by executives, with only “increasing social impact” receiving fewer votes. In a world where organizations are increasingly expected to deliver impact beyond shareholders to all stakeholders, executives who deprioritize well-being as a goal of work transformation are missing a huge opportunity.

Workers told us that the top three objectives of work transformation should be improving quality, increasing innovation, and improving worker well-being.

HR executives were slightly more deliberate than non-HR executives about focusing on well-being as an important outcome of work transformation, with 20% of HR executives selecting it as a priority compared to 15% of non-HR executives. But designing well-being into work cannot be done by HR alone. The incorporation of well-being into work must be done symphonically, championed by leaders at every level and in every function if it is to make a meaningful difference.

One especially important stakeholder for HR to involve is the organization’s technology leader. Technology and work today are inextricably intertwined, with humans and machines partnering in ways previously unimaginable to accelerate work outputs and achieve new outcomes. As technology becomes ingrained in every aspect of how people work, technology leaders will face a growing responsibility to work with HR and the business to ensure that those technologies, and the workflows and processes that complement them, are designed and executed in a way that promotes worker well-being.3

For example, the “right to disconnect” concept, which prompted a 2017 French law limiting the extent to which workers can be required to answer phone calls and emails during nonwork hours, recognizes that 24/7 access to emails and texts encourages an expectation of being “always on” that can compromise worker well-being.4 An innovative example of how technology can help counteract this problem is Daimler AG’s optional email functionality, “Mail on Holiday,” that automatically deletes incoming messages while people are taking time off. During that time, the system sends autoreplies that suggest alternative people to contact or prompt the sender to get back in touch when the worker returns.5

Technology leaders can take the imperative to design enabling technologies for well-being one step further by introducing new technologies to boost workers’ health, performance, and quality of life. Such technologies could include “emo tech” to help people develop self-awareness and emotional regulation; “collaboration, presence, and trust tech” to help people build deeper group connections; and “well tech” that helps people maintain and optimize health and cognition to support general well-being.6 Technologies such as these can improve well-being by allowing workers to better eliminate distractions, ease anxieties, connect with others, build presence and trust, and learn faster.

Emerging priorities

Organizations looking to build well-being into work should consider actions, policies, and mandates at three levels—individual, team, and organizational:

- Individual: Workers should take the initiative in setting their own boundaries and making their well-being needs understood. They should influence the prioritization and design of well-being by participating in the development of flexible and responsive policies and practices that balance individual needs with those of the team and the organization.

- Team: The power of teams comes from their ability to connect people with each other to unleash their collective capabilities. Tapping into those capabilities requires team members to understand and honor each individual’s well-being needs to create an environment in which the team can perform at its best.

- Organizational: Leaders have a responsibility not only to invest in and promote well-being, but also to commit to it by designing well-being into work and making well-being a consideration as important as any other factor that affects the bottom line.

By reinforcing their efforts across all three levels, organizations can harness well-being to drive improved outcomes in areas such as customer satisfaction, organizational brand and reputation, innovation, and adaptability.

Organizations should also take into account the environments in which they’re designing work, as work increasingly crosses cultures, geographies, functions, and physical and virtual workspaces. The suggestions below offer a starting point for leaders to think through what changes they can make in five environments across the three levels:

- Cultural: Building well-being into social behaviors and norms

- Relational: Fostering well-being in relationships among colleagues

- Operational: Including well-being in management policies, processes, and programs

- Physical: Designing the physical workspace to facilitate well-being

- Virtual: Designing new technologies and virtual workspaces for well-being

There are a variety of actions organizations can take to integrate well-being into work (figure 3).

The design of well-being into work is a practice that must be developed, strengthened, and flexed over time to be effective. As work itself changes at a rapid pace, the ways that an organization supports individual and team well-being must adapt in tandem. It’s no longer about achieving work/life balance; the pandemic has shown us that well-being is not about balancing work with life, but integrating them. When an organization is able to successfully design well-being into work, well-being becomes indistinguishable from work itself, embedded across all organizational levels and environments to not only drive and sustain human performance, but also human potential.

Acknowledgments

Jen Fisher co-authored our 2021 Global Human Capital Trends discussion on “Designing work for well-being: The end of work/life balance.” As Deloitte’s US chief well-being officer, Fisher drives the strategy and innovation around well-being to empower Deloitte’s people to be well so they can perform at their best in both their professional and personal lives.

The authors would like to thank Keren Wasserman for her leadership in the development of this chapter, and Amy Fields, Jaime Ledesma, and Michael Gilmartin for their outstanding contributions.

Read the 2020 trend on well-being

Beyond reskilling

Unleashing workforce potential

During COVID-19, leaders called upon workers to expand their roles to whatever needed to be done—and workers rose to the challenge, identifying critical needs and deploying their capabilities against them from the bottom up. The growing prevalence of worker agency and choice during the pandemic showed that, when given the chance to align their interests and passions with organizational needs, workers can fulfill their potential in ways that leaders may never have known they could, positioning the organization to thrive in the long term.

Shifting realities

Last year, we called on organizations to employ a workforce development approach that considers both the dynamic nature of jobs and the equally dynamic potential of workers to reinvent themselves. Even before COVID-19, it was clear that workforce development approaches that focused too narrowly on skills would not help organizations, workers, and leaders build the resilience required to navigate perpetual change. Then, organizations were faced with a pandemic that accentuated the scale of the impact disruption can have on organizations and the workforce. During the COVID-19 crisis, organizations did not have time to rewrite job descriptions or meticulously map skills requirements; they were forced to make real-time decisions and to redeploy workers to the areas where they were needed the most, and where they had the capabilities, interest, and passion to contribute. In short, 2020 has helped us understand the importance of worker potential and choice.

As author Natalie Nixon puts it, “The opposite of reactive might not be ‘proactive’ but instead ‘creative.’”7 We are seeing an explosion of creativity and the power of worker potential during the COVID-19 pandemic. Automotive workers used 3D scanners and computer simulations to retool their assembly lines to manufacture ventilators for COVID-19 patients.8 Beverage companies partnered with government organizations to clear administrative hurdles in order to rapidly produce and distribute hand sanitizer.9 And clothing manufacturers adapted production lines to make much needed surgical garments.10

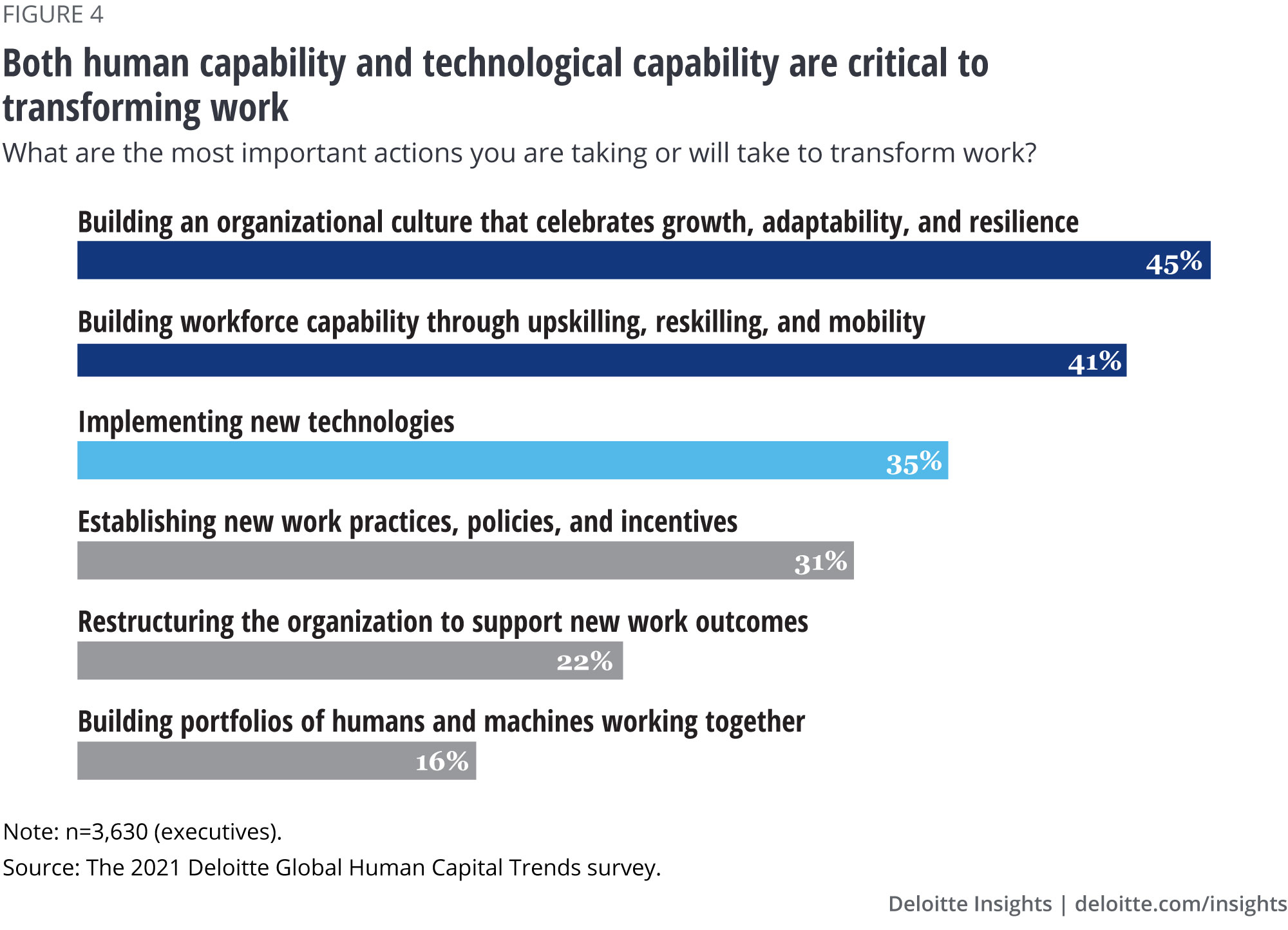

In the months of extended crisis recovery, executives have reflected on the challenging road ahead as they attempt to prepare their businesses and ecosystems for an era of continuous disruption. That preparedness depends on workforce potential. In the 2021 Deloitte Global Human Capital Trends survey, executives identified “the ability of their people to adapt, reskill, and assume new roles” as the top-ranked item to navigate future disruptions, with 72% selecting it as the most important or second most important factor. Further, 41% of executives said that building workforce capability through upskilling, reskilling, and mobility is one of the most important actions they are taking to transform work. Yet only 17% say their workers are very ready to adapt, reskill, and assume new roles. Workers themselves recognize the imperative to change as well, with 60% of the 10,000 workers in this year’s Voice of the European Workforce study identifying “capacity to adapt” as the most relevant skill they will need to thrive in the labor market.11

Our 2021 perspective

Our hypothesis: Empowering workers with agency and choice creates more value than overly prescriptive approaches

Organizations that afford workers the agency and choice to explore passion areas will be able to more quickly and effectively activate workers around emerging business priorities than organizations that take a prescriptive approach to filling skills needs.

In our view, the most important way that organizations can unleash workers’ potential is to empower them with agency and choice over what they do. We’ve lived in a world where we assumed organizations knew best what skills workers needed to bring to the table. But the pandemic taught us that potential comes to fuller fruition when workers are allowed to take more initiative. Workforce potential is not about what workers were recruited to do, or what they are certified to do, or even what organizations or leaders want them to do next. It’s about giving workers more freedom to choose how they can best help tackle critical business problems as organizations and ecosystems evolve.

One way to give workers more agency and choice in what they do is through “opportunity—or talent—marketplaces.” These marketplaces are platforms that make visible and communicate to workers defined opportunities for professional development, training, mentorship, project participation, networking, promotion, diversity, and inclusion.12 They’re designed to provide workers with choice by helping them match their interests, passions, and capabilities against current and future business and project demands. Such “passion projects” give workers new development experiences and opportunities to learn in the flow of work, further enhancing the skills they bring to the organization.

Opportunity marketplaces benefit organizations in several ways. By giving workers the chance to volunteer for work they prefer and value, they bring to light valuable information about workers’ interests, passions, and capabilities that may otherwise remain hidden. This, in turn, allows the organization to more quickly identify and redeploy workers against critical business priorities. At the same time, workers who are able to do what matters to them become more motivated and more engaged.

Capturing the insights that worker choice can help uncover requires a shift in frame from looking for gaps to sensing for evolving patterns and possibilities. To that end, a variety of vendors are employing new approaches to skills graphs and skills engines that break previous, limited understandings of skills adjacencies. Vendors from across a converging set of workforce technology domains, such as Gloat, Degreed, Eightfold, Faethm, Ibbaka, ProFinda, and Pymetrics, are focused less on a top-down inventorying of skills and more on helping organizations reimagine the relationships between skills, positions, teams, and industries to seize opportunities presented by the future of work and help workers reach their potential.

Payments technology company Mastercard exemplifies how a deeper understanding of worker potential can help inform workforce planning and development efforts. Following a period of rapid and extensive growth, Mastercard business and HR leaders realized that the organization needed a clear understanding of its workforce’s skills and capabilities, especially in light of technology-driven change. To clarify how roles and skills were changing as technology evolves, the organization invested in a forward-looking analytics platform, Faethm, that uses artificial intelligence (AI) to model emerging technologies’ impact on any economy, industry, organization, or job. During the pandemic, this platform has been key in guiding some decisions on work flexibility ranges. In the future, the organization plans to use the insights from this tool to guide day-to-day learning investments and, ultimately, support worker career progression. This analytics-driven approach has moved Mastercard beyond the traditional approach of identifying employee profiles from the top down and matching them with training needs. Instead, the technology infers employee profiles from the bottom up by analyzing multiple large-scale data sets from many systems and sources (such as performance management, job descriptions, learning management systems, and career conversations). This allows Mastercard to more accurately understand its workers’ skills to identify organization-wide strengths and development areas.

The deeper understanding of workers resulting from worker choice can help organizations break free of the constraints of traditional workforce planning models. Historically, workforce planning has relied on competency frameworks, static job descriptions, and linear career paths to define and organize work and the workforce. Efforts to prepare for the future have largely taken the form of a supply chain–inspired focus on pipelines for critical roles, with conversations about hot skills, skills gaps, and skills adjacencies dominating conversations around talent. But those conversations often lose sight of the latent potential within the workforce—and the value they can create when their potential is understood and harnessed. For instance, during the pandemic, Scandinavian Airlines recognized that its cabin staff members could be well suited for roles in health care due to their basic medical training and experience dealing with people in difficult situations. The organization created a program to rapidly retrain laid-off cabin staff as assistant nurses to meet rising health care staff needs during COVID-19. To date, this program has helped place more than 300 cabin attendants and people with equivalent experience from other sectors in Sweden’s health care system, fulfilling an important social need.13

Giving workers a voice in what they do also helps organizations act more dynamically and in real time. Top-down approaches based on identifying business needs and then finding or developing the skills to put against them will always be slower than approaches that allow workers to self-select based on their interests and abilities. The challenge here is to put guardrails in place that channel workers’ interests and abilities toward the good of the organization, allowing choice not for its own sake but because what is chosen helps the organization grow and thrive. Organizations that figure this out can benefit from the increased agility and resilience to change that are critical to navigating constant disruption.

Emerging priorities

The success of work transformation depends on an organization’s ability to unlock human potential to define and deliver new outcomes. Organizations that want to unlock human potential should consider actions in the following areas:

Shift the supply and demand equation

- Build talent marketplaces that actively address both sides of the workforce supply and demand equation. Marketplaces can expose business and project needs to workers and can expose workforce skills and capabilities to the organization.

- Design roles to assume ongoing reinvention and include excess capacity earmarked for it. Cultivate worker passions to solve unseen and future problems. Reward workers who identify critical gaps and reinvent themselves to fill them. New vendors such as Learn In can help provide time, not just money, allowing workers to engage in lifelong learning while limiting the typical opportunity costs.

Center workforce planning on potential

- Shift workforce planning approaches away from a reliance on top-down mandates, providing more agency to workers themselves. Empower workers to reimagine what, how, and where work gets done.

- Consider AI-enabled technologies that can help make sense of unstructured data from inside and outside the organization and surface latent patterns such as the inferred presence of one skill based on the presence of others. It’s important to ensure that such new AI tools are integrated into the strategy and that the implications of their deployment are understood and accepted by all stakeholders. They will struggle to get traction if their value is not acknowledged and demonstrated.

Drive toward real-time, dynamic action

- Gather and act on workforce data that provides a real-time view of workers’ skills across the entire talent ecosystem. Ask forward-looking questions about workers’ desired future directions rather than tracking prescriptive metrics such as hours spent in training or credentials earned, and use the answers to encourage workers to make learning choices that benefit both themselves and the organization.

- Remember that teams are becoming the driving unit of organizational performance. Teams will be able to learn and adapt faster than individual workers alone, since teams of motivated individuals will challenge each other to come up with better, more creative ideas.14

The year 2020 witnessed an amazing display of workforce adaptability. Extraordinary circumstances and challenges uncovered the potential of workers and teams when confronted with new, changing, and dramatic business and organizational problems and priorities. We saw that the workforce can adapt more dramatically than many would have expected when faced with new challenges. Going forward, the power of agency and choice, enabled by opportunity and talent marketplaces, can quickly connect changing work priorities with workers’ skills, experiences, and—importantly—their interests. 2020 also highlighted how little organizations actually know about their workforces—their skills and capabilities now and the capacity for ongoing reinvention. The challenge for organizations now is to develop strategies and programs for workforce development and deployment as dynamic and adaptable as the business problems we are trying to solve.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Greg Miller (Faethm), Brian Hershey (Gloat), Karen Chiang and Steven Forth (Ibbaka), Esther Gallo (Mastercard), Roger Gorman and Alpesh Patel (ProFinda), and Andrew Avrin and Bob Toohey (Pymetrics) for their contributions to this chapter. The authors would like to thank David Blake, executive chairman of Degreed and founder of Learn In, for his contributions to our perspective on investing in workforce skills and capabilities.

The authors would also like to thank Weatherly Langsett and Mackenzie Halter for their leadership in the development of this chapter, and Carly Ackerman, Nate Drix, Chris Ertel, Kira Gebron, Michael Griffiths, Julie Hiipakka, Don Miller, Stephen Rosenthal, Mel Rodriguez, Dana Swanson Switzer, and Lucas Watanabe for their contributions.

Read the 2020 trend on reskilling

Superteams

Where work happens

During the COVID-19 pandemic, organizations doubled down on teams and teaming as a survival strategy to enable adaptability and speed. Leaders now have the opportunity to use what they have learned to construct “superteams” that pair people with technology to re-architect work in more human ways. By amplifying humans’ contributions to new and better outcomes, superteams can play an integral part in an organization’s ability to grow and thrive.

Shifting realities

In early 2020, the escalating COVID-19 pandemic forced organizational leaders to quickly reset business and workforce priorities. The pandemic’s scale and severity forced organizations to challenge their views about what work was essential to deliver to their customers, shareholders, and stakeholders during a prolonged period of heightened uncertainty. To rapidly reorient their goals and operations, we saw organizations turn to teams and teaming as the go-to unit for organizational performance. For example, Ford formed special teams and set up new production lines in its manufacturing facilities to shift from making hybrid car batteries to tens of thousands of ventilators.15 Teams, newly forming, growing, and reconfiguring, were supercharging organizations’ ability to pivot and get work done amid turbulent and demanding conditions.

Teaming became a life raft for talent and organizational strategies during COVID-19 because teams are built for adaptability rather than predictability and stability. Teams can learn and adapt faster than individual workers alone, since teams of motivated individuals will challenge each other to come up with better, more creative ideas.16 As organizations shift from a focus on efficiency to a focus on learning, we expect them to increase their reliance on teams to drive growth and navigate uncertainty.

As the world emerges from the pandemic, organizations have an opportunity to use what they have learned to multiply the value of teams even further. The next frontier in teaming is superteams: combinations of people and technology leveraging their complementary capabilities to pursue outcomes at a speed and scale not otherwise possible.17

Superteams have yet to take hold as a widespread organizational strategy, in part because many organizations still tend to view technology as a tool and enabler rather than as a team member and collaborator. Most respondents to our 2020 Global Human Capital Trends survey, for example, said they view artificial intelligence (AI) mainly as an automation tool—a substitute for manual labor—rather than a way to augment or collaborate with human capabilities. However, this view may be slowly starting to change. Executives responding to the 2021 Deloitte Global Human Capital Trends survey recognized that the use of technology and people is not an “either-or” choice but a “both-and” partnership.

The top three factors executives identified as important in transforming work were organizational culture, workforce capability, and technology (figure 4)—factors that must all work together for an organization to envision and assemble effective superteams.

AI can be especially important to a superteam’s ability to create new value. In organizational psychology, what Scott Page calls a “diversity bonus” results from forming teams composed of different kinds of thinkers, meaning that heterogeneous teams outperform homogenous ones at solving problems, making predictions, and developing solutions. Research shows that organizations with above-average diversity produced a greater proportion of revenue from innovation (45% of total) than those with below-average diversity (26%), which translated into stronger overall financial performance.18 With AI bringing its own style of “thinking” to a team, the mix of human and machine intelligence can yield diversity bonuses that exceed those produced by teams composed of only humans, however diverse.19

That said, sometimes adding technology may not be the right answer, and doubling down on human capabilities may be a better approach. For example, Walmart has ended its program to use robots to check the inventory on store shelves in favor of using human workers instead. Even as demand ballooned during the pandemic, the organization found that managing its on-shelf products could be done just as simply and cost-effectively by its people as by the robots.20

Our 2021 perspective

Our hypothesis

Superteams can give organizations the opportunity to re-architect work in more human ways, leveraging technology to elevate teams’ ability to learn, create, and perform in new ways to achieve better outcomes.

The big payoff from superteams is not just that they can get work done faster and cheaper. Rather, their greatest value lies in their potential to re-architect work, using technology to change the nature of work so that it makes the most of people’s distinctly human capabilities. Doing this goes beyond considerations of user experience and human-centered design. And as the Walmart story shows, it’s not just a matter of using technology to perform parts of the work. It means deliberately using a superteam’s complementary human and technological strengths to design work so that it enhances humans’ natural ways of working. The following three examples highlight that when technology is combined with humans in superteams, it can enable distinctly more human ways of working that lead to distinctly better outcomes.

Often, people do their best work when they work in teams. The collaboration tools that made remote and virtual work possible during COVID-19 also prompted some organizations to rethink how those technologies could be used to team far more effectively across organizational and ecosystem boundaries. For instance, in its response to COVID-19, AstraZeneca, one of the world's leading pharmaceutical companies, pulled together hundreds of scientists from across therapeutic areas—respiratory, cardiology, and oncology, among others—and from the University of Oxford to work together to develop a vaccine and other therapeutics. Additionally, AstraZeneca played a critical role in setting up the testing laboratories for the national testing program within the United Kingdom, enlisting scientists from across its organization and from its partnerships with the University of Cambridge Laboratories and GlaxoSmithKline. The organization used collaboration technologies to enable real-time partnership and data-sharing that increased the speed and level of the teamwork necessary for rapid progress.21

Technology can also enhance people’s natural powers of judgment. For instance, the insurance industry is experimenting with AI and predictive modeling to evolve the traditional underwriter role. As application processing moves closer to the point of sale, AI can provide data-driven suggestions to increase underwriters’ ability to make informed decisions about risk. These “exponential underwriters” don’t have to become tech experts or data scientists to use and benefit from the technology. They only need to understand how and when to leverage AI-assisted solutions to accomplish the work more effectively, fulfilling their role in the human-machine collaboration.

Finally, technology can improve people’s uniquely human ability to create new knowledge. One example comes from Remesh, a company that helps to facilitate live, online focus groups at scale using an AI-enabled platform. Remesh uses AI to analyze and organize responses in real time and capture insights arising from the answers. Not only does this deliver insights faster, but it also improves the quality of the insights by surfacing views that might otherwise not emerge. The platform prompts participants to vote on which responses from other anonymous participants they agree with the most. Its algorithms then automatically calculate and rank responses based on group popularity, allowing for a clear view into participants’ ideas unclouded by factors such as bias and individual personality differences.

Emerging priorities

The 2021 Deloitte Global Human Capital Trends survey showed that executives are shifting their focus away from work optimization and redesign toward work reimagination, with 61% saying that they would focus on reimagining work going forward as opposed to 29% before the pandemic. But to move from optimization and redesign to reimagination, organizations must also change the way they’re leveraging technology in work. Work optimization and work redesign focus on achieving the same work outputs more efficiently, so they largely depend on using technology to substitute or augment human work. Work reimagination, on the other hand, uses technology to transform the nature of work in ways that achieve new outcomes and make possible new aspirations.

To create an environment where superteams flourish, executives should consider the following:

- Set audacious goals. Stop focusing on how to improve existing processes and outputs and instead focus on defining new aspirations and outcomes.

- Don’t stop with envisioning new ways to achieve those outcomes. Re-architect the work to put reimagination into action.

- Avoid the instinct to use technologies only as an enabler for the work you already do. Instead, take a broader view of technology’s transformative potential to elevate the impact it can have on work.

- Use technology to design work in ways that allow humans to perform at their best: working collaboratively in teams, breaking down silos to work across functions and businesses, creating knowledge, learning in the flow of work, and personalizing and humanizing the work experience.

- Make the creation of superteams a cross-organizational imperative, leveraging the best thinking from HR, IT, and the business.

Superteams are most powerful when organizations use technology to empower teams in a way that makes work better for humans and makes humans better at work. They hold the promise of helping organizations bring human and technological capabilities together to re-architect work and deliver new value to all stakeholders. When given the right environment to thrive, superteams of humans and technology together can unlock organizational potential and achieve greater results together than either humans or machines could achieve on their own.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Steve Rees and Tonya Villafana (AstraZeneca) for their contributions to this chapter.

The authors would also like to thank Olivia Fogel for her leadership in the development of this chapter, and Siri Anderson, Balaji Bondili, Olivia Cancro, Patricia Danielecki, Chloe Domergue, Nate Drix, Sam Friedman, Franz Gilbert, Nikhil Gokhale, Susan Hogan, Michael Morgan, Nicole Nodi, Mel Rodriguez, Stephen Rosenthal, Ben Shirley, Brett Walsh, and Marilyn Zubak for their contributions.

Read the 2020 trend on superteams

Governing workforce strategies

Setting new directions for work and the workforce

COVID-19 was a rude awakening that governing workforce strategies using retrospective metrics and measurements describing the workforce’s current state severely limits an organization’s ability to survive disruption, let alone thrive in it. Asking and answering different questions—questions that push leaders to constantly challenge their approaches to work and the workforce—can help organizations meet constant change with the confidence that comes from thinking and looking ahead.

Shifting realities

The need for organizations to better understand their workforce is under urgent pressure from unprecedented, once-in-a-lifetime health, economic, and social challenges. The COVID-19 pandemic is raising critical health issues around employee well-being and safety, as well as remote work and alternate workforce arrangements. The pandemic’s economic fallout is forcing employers to make tough decisions about staffing levels, worker and team redeployment, and worker retention. And a dramatically intensified focus on social and racial injustice in the United States—and its widening ripple effect—is drawing significant attention to companies’ diversity, equity, and inclusion (DE&I) efforts and results.

These challenges have exacerbated an employer-workforce information gap that our research identified more than a year ago. Ninety-seven percent of respondents to our 2020 Deloitte Global Human Capital Trends survey stated that they need additional information on some aspect of their workforce. Only 11% of organizations said they were able to produce information on their workforce in real time—a statistic that was staggering even before organizations were forced to make a series of immediate pandemic-driven decisions about their workforce.

In our 2020 special report, Returning to work in the future of work: Embracing purpose, potential, perspective, and possibility during COVID-19, we explained how the pandemic has highlighted and accelerated “the need for and ease of access to insightful and future-oriented workforce data.”22 We encouraged organizations to ask different questions and measure and report the answers in real time in order to shed light on important workforce issues, have discussions about them, and move to action. These forward-looking insights, not backward-looking, stale data, can help organizations understand how to achieve new outcomes by harnessing workforce potential and transforming work.

For instance, understanding workers’ immediate concerns and preferences can be an invaluable guide to when and how to bring them safely back to work during and after the COVID-19 pandemic. Financial services provider Lincoln Financial took a multidimensional approach to gaining these insights, using employee surveys and advanced analytics to collect information that could help it effectively design its return-to-work strategy. The surveys allowed leaders to identify a range of worker personas reflecting workers' safety concerns, flexibility desires, and their individual effectiveness in a remote environment. Insights into the roles most affected by virtual work highlighted the potential impacts to productivity, collaboration, and relationship-building. Using these workforce sentiment analyses, Lincoln Financial’s leaders were able to design future ways of working to boost productivity and engagement while maintaining an all-important focus on workforce safety and mental wellness.

Our 2021 perspective

Our hypothesis

We’re entering a world in which it’s becoming paramount that organizations shift from using workforce insights to improve old patterns of work to using it to set new directions.

Results from the 2021 Deloitte Global Human Capital Trends survey showed that COVID-19 has prompted many organizations to shift their approach to preparedness from planning for likely, incremental events to anticipating unlikely, high-impact events and considering multiple possible scenarios. Seventeen percent of executives said that their organizations would focus on unlikely, high-impact events moving forward, as opposed to 6% before the pandemic. And 47% said that their organizations planned to focus on multiple scenarios in the future, up from 23% before the pandemic.

To effectively deal with multiple possible futures and unlikely events, organizations need to be able to quickly pivot and set new directions—which depends, in large part, on the ability to access and act on real-time workforce insights. The new element here is the use of workforce strategies to plan for uncertainty. A more dynamic, action-oriented approach to understanding the workforce can help leaders make better, faster decisions based on up-to-the-minute information on what their workforce is capable of.

Enabling such a dynamic approach requires tying workforce data to both economic value and organizational values, using it to gain insights on how to grow and thrive in the marketplace as well as on how to align worker and organizational behavior with an organization’s principles. It means mining workforce data for insights that are useful not only to leaders and workers internally, but also to the external community. It involves sharing workforce data and the insights it supports with leaders, workers, and the community in order to drive both direction and accountability. And it means having up-to-date insights always at your fingertips, because in a constantly changing environment, an organization must constantly be setting new directions as well.

To achieve a more dynamic workforce strategy, organizations across countries are exploring new approaches to gaining deeper workforce insights. While these approaches vary to accommodate different national laws, regulations, and norms, the common thread is a movement toward greater transparency and a stronger call to action.

One powerful example of using workforce insights to prompt movement toward new outcomes is the DE&I advances made by Edison International and its largest subsidiary, Southern California Edison (SCE). SCE not only publishes its DE&I data on its external website but has undertaken initiatives to understand and act on this data at a deeper level. Its efforts include a series of listening tours beginning with Black employees in partnership with Networkers, SCE’s business resource group (BRG) dedicated to advancing inclusion for Black employees, to better understand their experiences and an in-depth gender-focused study on pay in partnership with SCE’s Women’s Roundtable BRG. In 2020, SCE demonstrated its commitment to DE&I by publicly sharing information on representation by race and gender across pay, access, and employee sentiment; the status of its suppliers; and its community investment. Finally, the organization has announced a series of actions to advance social and economic equity in SCE communities, with an initial increased commitment to the Black community. As SCE’s VP, People, Culture & Strategy explained, “We’ve done a lot of really good work not only just releasing the data transparently but acting on it. We have commitments, both internally and externally, that we’ve made public.”

Emerging priorities

In our 2020 Deloitte Global Human Capital Trends report, we compiled a list of key questions that leaders should be asking to gain real-time insights about workforce productivity, their well-being, and their priorities, as well as DE&I metrics. This year, we explore three themes—worker potential, talent ecosystems, and translating organizational values into action—that have emerged from the past year's events to see how answering these questions can help organizations set new work and workforce directions for the future.

Capitalizing on worker potential

In 2020, organizations experienced an unprecedented need to redeploy skills and rethink work outputs as they struggled to deal with the pandemic and its economic fallout. COVID-19 was a forcing mechanism for workers and leaders to consider how to apply their workforce in new ways to address new needs. Employers called on workers to extend their remit to all necessary tasks, whether or not those tasks fell within their preexisting roles. In tandem, jobs and roles underwent a de facto expansion to reflect what workers were actually doing. And workers proved that they were capable of reaching far beyond their job descriptions when their potential to do so was tapped.

Along the way, organizations learned that their definitions of what work needs to be done, who needs to do it, and how to motivate people to achieve their greatest potential can be much more fluid than they had previously supposed. If leaders take this lesson to heart, we may be headed toward an environment where organizations reevaluate the nature of work and jobs, not just when forced to by a crisis, but on an ongoing basis to anticipate rapid environmental shifts. Organizations will need to be vigilant about capturing employees’ potential in a data-driven way so that they know what capabilities the organization can draw upon at a moment’s notice.

Meanwhile, adroit leadership will become even more important at all organizational levels, of individual groups and teams as well as in the C-suite. Sixty percent of the executives in the 2021 Deloitte Global Human Capital Trends survey said that leadership was important to prepare for unknown futures—the top-ranked priority for supporting preparedness. And while much of leadership has historically been about setting direction and ensuring compliance, now effective leadership is shifting to preparing for the unpredictable by coaching, teaming, and fostering workers’ ability to learn and adapt. Team leaders are the ones best placed to recognize potential within their teams; they are the people on the ground who can identify who has the capabilities to do what and how those capabilities could be best applied. This means that in addition to capturing workers’ potential for growth and adaptability, organizations should strive to capture leaders’ ability to cultivate potential as well.

Questions to ask to capitalize on worker potential

- Job evolution: How often are jobs changing, which ones, and to what degree?

- Future workforce readiness: How ready is our workforce to perform the work of the future? What are our capability, experience, and skill gaps, and how are we going to close them?

- Change ability and agility: Are workers and leaders able to quickly and effectively adapt to constant change?

- Future leader readiness: What new trends, challenges, and scenarios are leaders being prepared for? How many of our leaders have the attributes required to succeed?

Tapping into the entire talent ecosystem

As many organizations were discovering they could expand responsibilities and roles, many also realized that a clearer view of—and greater access to—their entire talent ecosystem could make these efforts far more effective. The more precisely an organization knows where to find the capabilities to do what’s needed, and the better able it is to access those capabilities, the more effectively it can deploy and redeploy people to plug operational gaps. This need is especially evident at organizations that are drawing heavily on alternative workers, whether because they are growing quickly and need extra workers to support their growth, or because they needed to reduce on-balance-sheet headcount and are using alternative workers as a more flexible substitute.

This realization reminds us how important it is to be able to immediately access needed capabilities, wherever they may reside. Because of this, we expect organizations to implement common systems for tracking, measuring, and governing workers across both the traditional and the alternative workforce. Further, as the pandemic has driven organizations’ need to flex their workforce up or down, it’s become clear that the talent ecosystem should also extend to workers who have separated from the organization, such as alumni and retirees. Maintaining a data-driven pulse on these separated workers can help an organization track and engage them in case they’re needed once again.

In fact, getting the most value out of a talent ecosystem requires organizations to view the concept of retention differently. It’s less about tracking how many people leave as it is about understanding who is leaving and why. Unlike simple retention rate metrics, understanding who is leaving and why can shed light on whether these patterns are desirable or undesirable and inform strategies to make appropriate adjustments. It’s the difference between knowing that 1.1 million workers dropped out of the US labor force in September 2020—and understanding that 80% of those workers were women,23 a statistic with clear diversity, equity, and inclusion (DE&I) implications.

New approaches to retention should also focus on how to build and maintain relationships with different parts of the workforce ecosystem, whether traditional workers, alternative workers, part-time workers, or former workers. Being able to identify all talent segments across the ecosystem is important, as is understanding workers’ skills, motivations, and employment preferences in each segment. Data-based insights into questions such as these can enable organizations to more easily tailor their workforce to evolving needs.

Questions to ask to tap into the entire talent ecosystem

- Workforce footprint: How many workers provide direct or indirect services to our organization?

- Internal talent market health: How healthy is our internal talent market?

- Talent ecosystem health: How much capability can we access across our broader ecosystem?

- Retention drivers: Which of our workers are at risk of leaving, and why?

Translating values into action

2020 saw a series of events that focused renewed attention on organizational values, such as ethics, fairness, and inclusivity, around the world. Explosive race-driven incidents in the United States prompted organizations to examine their commitment to DE&I, while widespread layoffs and furloughs put a spotlight on the quality of the social contract between employers and workers. Customers asked organizational leaders, and organizational leaders asked themselves, their partners, and their suppliers, to deeply examine what they were doing to promote principled individual and organizational behavior—with the expectation that everyone needs to do more.

Especially evident during COVID-19 has been the way the pandemic has affected the employer-worker social contract, particularly as it relates to well-being. Many employers enhanced their focus on their workers’ well-being, and this was not limited to efforts to keep workers from being infected. For example, 69% of our surveyed executives said that their organizations put changes in place during COVID-19 that they thought empowered workers to better integrate their personal and professional lives.

To make outcomes such as this even stronger, it’s important to find actionable ways to use and share information to make measurable progress in new directions. This is where an organization’s sensing capabilities—covering its entire workforce ecosystem, conducted in multiple ways through multiple channels, and performed continually rather than periodically—become paramount. A complex and shifting environment makes it impossible to rely on point-in-time data or data that covers only part of the workforce. Instead, an organization needs a holistic view of its people’s sentiments, norms, and behaviors to understand its culture, pinpoint risks, and decide what must be done to achieve its aspirations. Equally important, organizations also need ways to sense sentiment in the external world so that they can understand and manage how they are perceived by others.

The insights gained from internal and external sensing data can help organizations better align individual and organizational actions with the organization’s values. The data can and should also be transparently communicated to external stakeholders to inspire confidence in the organization’s integrity and ethics.

As disruption becomes the new normal, organizations are being forced to constantly reassess and reimagine their work, workforce, and workplace strategies. This calls for leaders to fundamentally shift their workforce governance practices by collecting real-time, forward-looking data at the intersection of economic value and social values. But collecting data for its own sake is not the goal. Data-driven insights can enable organizations to constantly challenge the actions they are taking and help determine whether and how they can shift those actions at need. The challenge is to avoid getting caught up in the mechanics of collecting data when the focus should be on using it to inform meaningful action toward new outcomes.

Questions to ask to translate values into action

- Workforce social contract: How does our organization treat its employees, contractors, and service providers of every type?

- Meaningful diversity: Are workers from diverse communities in a position to wield influence in the organization?

- Human capital brand: How is our culture, workforce, and leadership being portrayed externally?

- Culture risk sensing: What signals are we seeing that point to outliers in worker behaviors and norms?

The priority moving forward is to ensure that organizations’ efforts around workforce strategies, data, and insights span the range of stakeholders and that the lens is wide enough to include both short- and long-term measures of progress against economic and societal goals. Doing so will improve organizations’ ability to meet evolving talent needs, build flexibility and resilience, and drive new and better workforce management and results in a world of perpetual disruption.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Natalie Schilling, Liji Mary Thomas, and Jacqueline Trapp (Southern California Edison), for their contributions to this chapter.

The authors would also like to thank Brittany Whitehead for her leadership in the development of this chapter, and Amel Arhab, Chad Buege, Christina Dorfhube, Liz Dunne, Jason Flynn, Allyson Kuper, Melanie Langsett, Art Mazor, Lee Merovitz, Kirsty Miller, Ido Namir, Nicole Overly, Jennifer Rocks, Sophie Simpson, and Tina Whitney for their contributions.

Read the 2020 trend on governing workforce strategies

A memo to HR

Accelerating the shift to re-architecting work

COVID-19 required people to work in radically new ways, whether remotely using technology or in-person with safety and social distancing procedures in place. In addressing these challenges, HR was thrust to the forefront of organizations’ efforts to survive the crisis—and gained greater credibility among business executives as a result. As organizations emerge from the pandemic, HR has the opportunity to build on its newly enhanced position to shift its role from managing workers to re-architecting work, driving better outcomes that position organizations to thrive.

Shifting realities

In our Memo to HR in the 2020 Deloitte Global Human Capital Trends report, we called for a bolder, “exponential” HR, one that would expand its focus and extend its influence to better address organizations’ workforce and business issues.24 The outbreak of COVID-19 gave many HR organizations the chance to do just that. Workforce issues became central business issues as organizations, workers, and leaders strove to adopt new mindsets and ways of working. This compelled HR organizations across sectors and geographies to quickly and creatively solve both workforce and business problems. In doing so, many demonstrated a shift away from their traditional role of standardizing and enforcing workforce policies to a new responsibility of orchestrating work in an agile fashion across the enterprise.

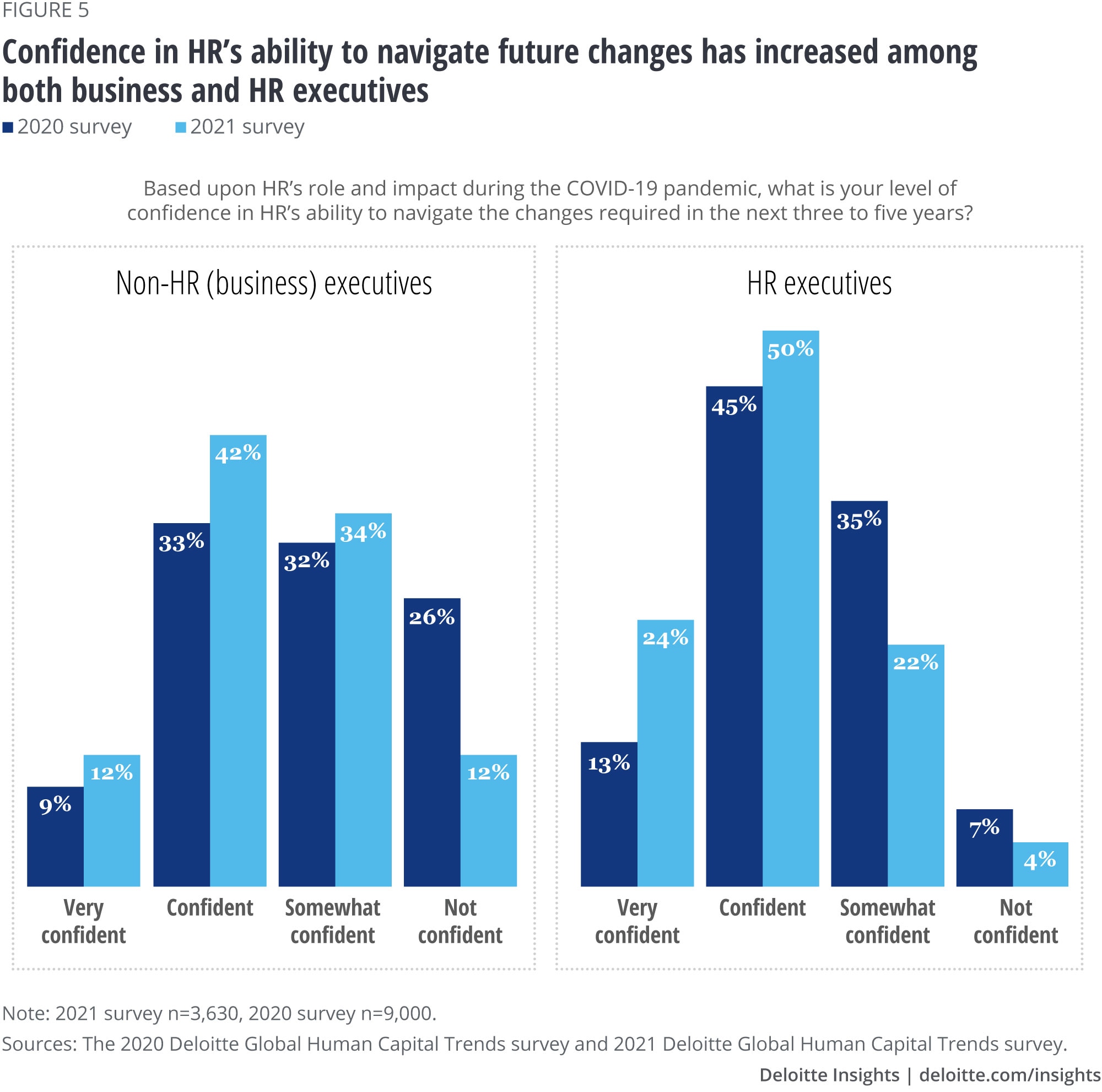

As a result of HR’s handling of COVID-19’s challenges, both business and HR leaders have become more confident in HR’s ability to help organizations navigate future changes. The 2021 Deloitte Global Human Capital Trends survey showed that the proportion of HR executives who were very confident in HR’s ability to navigate future changes doubled, from one in eight in 2019 to nearly one in four in 2020 (figure 5). Confidence in HR among business executives also increased, and the proportion that were “not confident” in HR dropped dramatically from 26% in 2019 to 12% in 2020.

Perhaps even more powerfully, respondents who expressed confidence in HR also experienced more positive outcomes.

Executives that were very confident in HR’s ability to navigate changes in the next three to five years were 2.9 times more likely to report that their organization was very ready to adapt, reskill, and assume new roles. They were also 2.6 times more likely to strongly agree that the changes their organization put in place during the pandemic empowered workers to successfully integrate the demands of their personal and professional lives. And they were 2.2 times more likely to report being very ready to make or pivot investments for changing business demands.

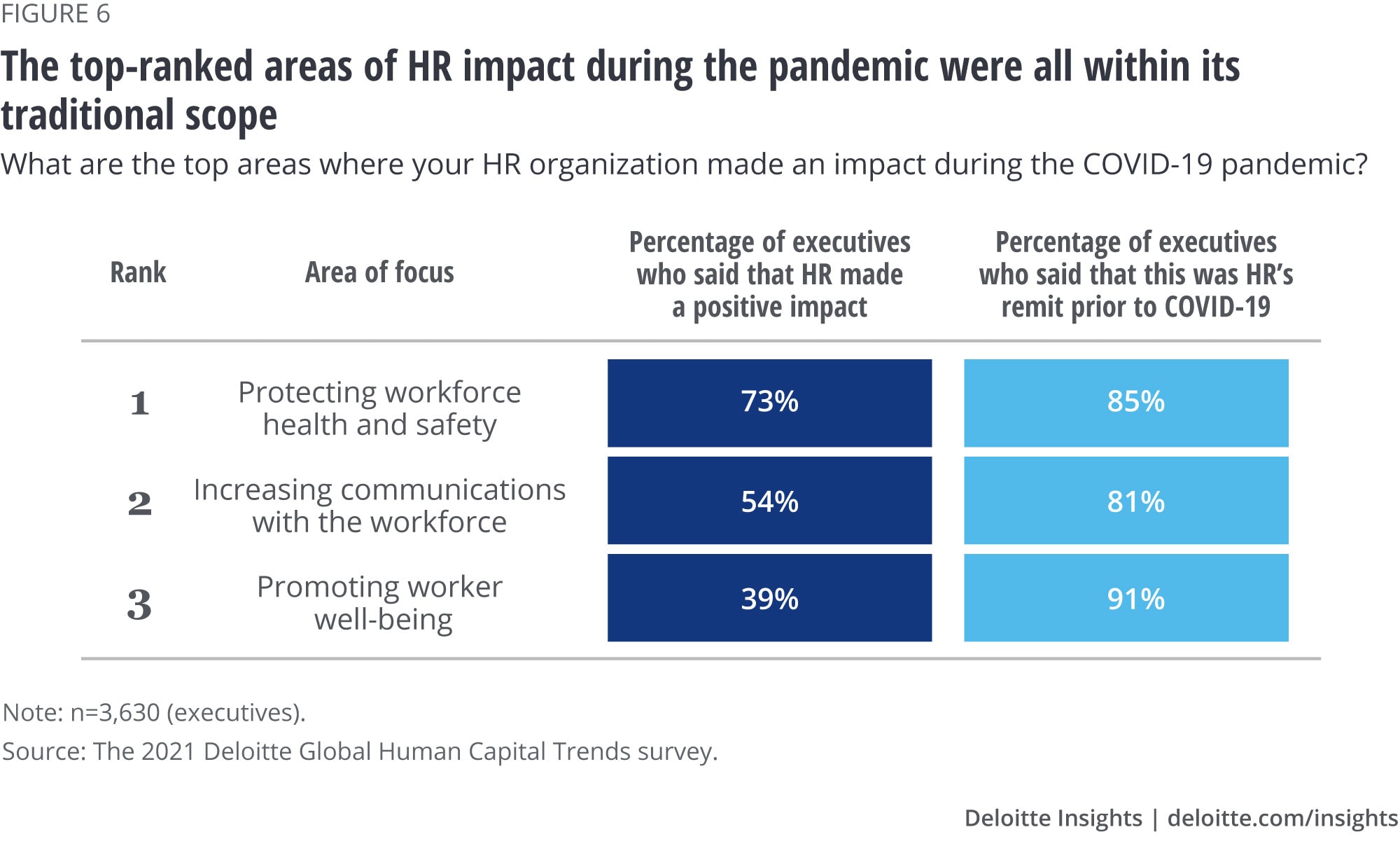

This is good news for HR. However, our survey data also shows that HR’s highest areas of impact during the pandemic were those within its traditional scope (figure 6). The question now becomes: With HR having created positive momentum and increased business executives’ confidence, how can it capitalize on that momentum to go beyond what is being asked for to what can be? How can HR use this window of opportunity to move from a functional mindset to an enterprise and impact mindset—one that expands HR’s focus and extends its influence from process to mission, from the worker to the human, and from managing workers to re-architecting work?

This isn’t just an academic question. To best help an organization grow and thrive, HR must lean into broader notions of its remit and move from optimizing to redesigning to re-architecting work and reimagining work-related challenges. The reason is simple. When HR has this mindset, organizations are more resilient, workers are more empowered, and organizations achieve better results.

Re-architecting work: Reimagination in action

Throughout this report, we’ve spoken a great deal about “reimagining” work. To achieve new outcomes and new value takes a step beyond reimagination, however. That step is re-architecting work. While reimagining is the destination, re-architecting is, in our view, the path to get there. That’s because re-architecture enables us to put reimagination into action. It’s one thing to envision new work outcomes, but it’s quite another to be able to craft those outcomes in a way that unlocks human potential and that models not just how work will be done, but how it will be experienced and lived. Re-architecting work, the how of effecting change, takes the potential of reimagination and turns it into reality. It is the final step that empowers organizations to truly thrive.

Our 2021 perspective

Our hypothesis

COVID-19 has earned many HR organizations the right to be bolder in orchestrating work throughout the enterprise. To seize this opportunity, HR needs to reorient its mission and mindset towards shaping future success by taking the lead in re-architecting work and reimagining the workforce and workplace accordingly.

HR's adoption of an enterprise mindset isn’t about reorganizing or restructuring the HR organization, although this is likely a required enabler. It’s not even about getting HR a “seat at the table” (it has had a seat at the executive table for a long time). Rather, it means centering HR’s role on the responsibility to own and re-architect work throughout the organization. When thoughtfully done, re-architecting work can drive new outcomes that create positive changes, from higher productivity to increased agility to greater innovation.

COVID-19 appears to have heightened leaders’ awareness of these potential benefits. In our survey, 61% of combined business and HR executives said that they would focus their thinking around work transformation on reimagining work in the next one to three years; only 29% said that this was the case before the pandemic.

Successfully re-architecting work will require several changes in how both HR and the organization approach work, teams, and capabilities:

- Shifting the focus of work from outputs to outcomes. This change in mindset is critical for achieving results beyond doing what is done today cheaper and faster to doing what is needed to pursue new outcomes and better results

- Looking at the re-architecture of work not as a one-time project or initiative, but as an ongoing capability that needs to be embedded into the organization’s operations

- Putting teams and superteams at the center of how work gets done. This will be needed both within HR and across the broader enterprise to spark innovation

- Approaching workforce development by identifying, cultivating, and capitalizing on workers’ potential, with a focus on uniquely human capabilities such as analysis and synthesis, problem-solving, and social intelligence

- Expanding the definition of capabilities to include the integration of both human and technological capabilities

- Recognizing and proactively managing the leadership and cultural implications that come from embracing new ways of working

Emerging priorities

Some of the most immediate needs for the re-architecture of work fall within the remit of HR itself, given the increasing criticality of work and work-related issues. The chart at the bottom of figure 7 shows the progression of new outcomes HR can drive in the context of the four other trends we’ve highlighted in this report.

The common thread running through these examples is a broadening of outcomes, an expansion of focus, and as a result, increased value to the organization. To see this in action, consider the issue of remote work. A traditional HR response might focus on, for example, providing well-being subsidies to cover ergonomic chairs for home offices—and this is a positive action. But by looking more broadly, HR can make a more substantive impact in addition to supporting workers’ physical health. Underlying the shift to remote work is the idea that leaders must manage, support, and develop people who are working in radically different ways. Understanding what effective leadership entails under these circumstances gives HR an opportunity to pull a thread to see what may be ahead: to better understand what the organization’s leaders are doing, determine if they have the right competencies, shape leadership development plans and performance indicators and incentives, and, ultimately, prepare next-generation leaders for a future where much of the workforce may be working remotely and flexibly.

Getting to the “re-architect” state will require developing and improving skills and capabilities, such as integrative thinking and a talent for collaboration. Even more importantly, re-architecting work calls for HR to learn from and partner with workers themselves to identify opportunities and craft new approaches. HR cannot gain a clear view of the depth and breadth of an organization’s work from a distance; it needs workers as a guide to uncovering ways to mold the work in ways that move the organization forward. This means making a shift from treating workers mechanistically to treating them as a creative force.

Doing all this effectively means that HR’s agenda must become one with the business agenda. HR must work closely with other stakeholders throughout the organization, enlisting their collaboration and guidance in the re-architecture of work. In this way, HR can serve as a model of integrative thinking and behavior for the rest of the organization. It’s an opportunity for HR to lead, through example, the organization’s journey to a more “symphonic” way of being.

The experiences of COVID-19 have opened a new door for HR to drive differentiated value for the business and the workforce. Now it’s time for HR to step through this door and begin to realize its true potential as an architect of work. By embracing this role, HR can extend its influence and impact across the entire organization and expand its focus across the entire workforce—not for the sake of HR but to push the organization toward its broader economic and human goals.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Stefano Costanzo and Farhath Feroz for their leadership in the development of this chapter, and Jodi Baker Calamai, Richard Coombes, Pip Dexter, Nate Drix, Kira Gerbon, Art Mazor, Dana Swanson Switzer, and Sam Tsang for their contributions.

Read the 2020 trend on HR

© 2021. See Terms of Use for more information.

Explore the collection

-

Global Human Capital Trends 2021: The social enterprise in a world disrupted Article4 years ago

-

2021 Global Human Capital Trends: Leading the shift from survive to thrive Article4 years ago

-

Designing work for well-being Article4 years ago

-

Beyond reskilling Article4 years ago

-

Superteams Article4 years ago

-

A memo to HR Article4 years ago