Beyond reskilling Investing in resilience for uncertain futures

13 minute read

15 May 2020

A system that invests not just in workers’ near-term skill needs but also in workers’ long-term resilience can help build long-term organizational resilience in a world where the only constant is change.

2021 Global Human Capital Trends

Sign up to receive a copy of our new approach to Trends launching this winter

Reskilling alone may be a strategic dead end. Renewing workers’ skills is a tactical necessity, but reskilling is not a sufficient path forward by itself. The skill shortage is too great. The investments are too small. The pace of change is too rapid, quickly rendering even “successful” reskilling efforts obsolete. What is needed is a worker development approach that considers both the dynamic nature of jobs and the equally dynamic potential of people to reinvent themselves. To do this effectively, organizations should focus on building workers’ resilience for both the short and the long term—a focus that can allow organizations to increase their own resilience in the face of constant change.

The Readiness Gap: Seventy-four percent of organizations say reskilling the workforce is important or very important for their success over the next 12–18 months, but only 10 percent say they are very ready to address this trend.

Learn more

Explore the Human Capital Trends collection

Watch the video

Learn about Deloitte's services

Order a copy of Work Disrupted, Deloitte's new book on the accelerated future of work

Explore 5 lessons from the pandemic for the future of work

Go straight to smart. Get the Deloitte Insights app

Current drivers

Organizations are struggling to navigate the fast-changing skills landscape. In our 2020 Global Human Capital Trends survey, 53 percent of respondents said that between half and all of their workforce will need to change their skills and capabilities in the next three years. It will be no easy feat for organizations to navigate this explosive rate of change effectively. They are up against a dramatically changing business landscape with constantly shifting skills and capability needs, greater expectations of organizations to respond to workforce development needs, and a lack of insights and investment to pave a clear path forward.

Today, the qualities that workers—and organizations—need to survive and thrive are very different from those they needed in the past. One reason for this is that economies are shifting from an age of production to an age of imagination. In the past, business success relied mainly on deploying precisely calibrated skills to efficiently construct products or deliver services at scale. Today, success increasingly depends on innovation, entrepreneurship, and other forms of creativity that rely not just on skills, but also on less quantifiable capabilities such as critical thinking, emotional intelligence, and collaboration.1

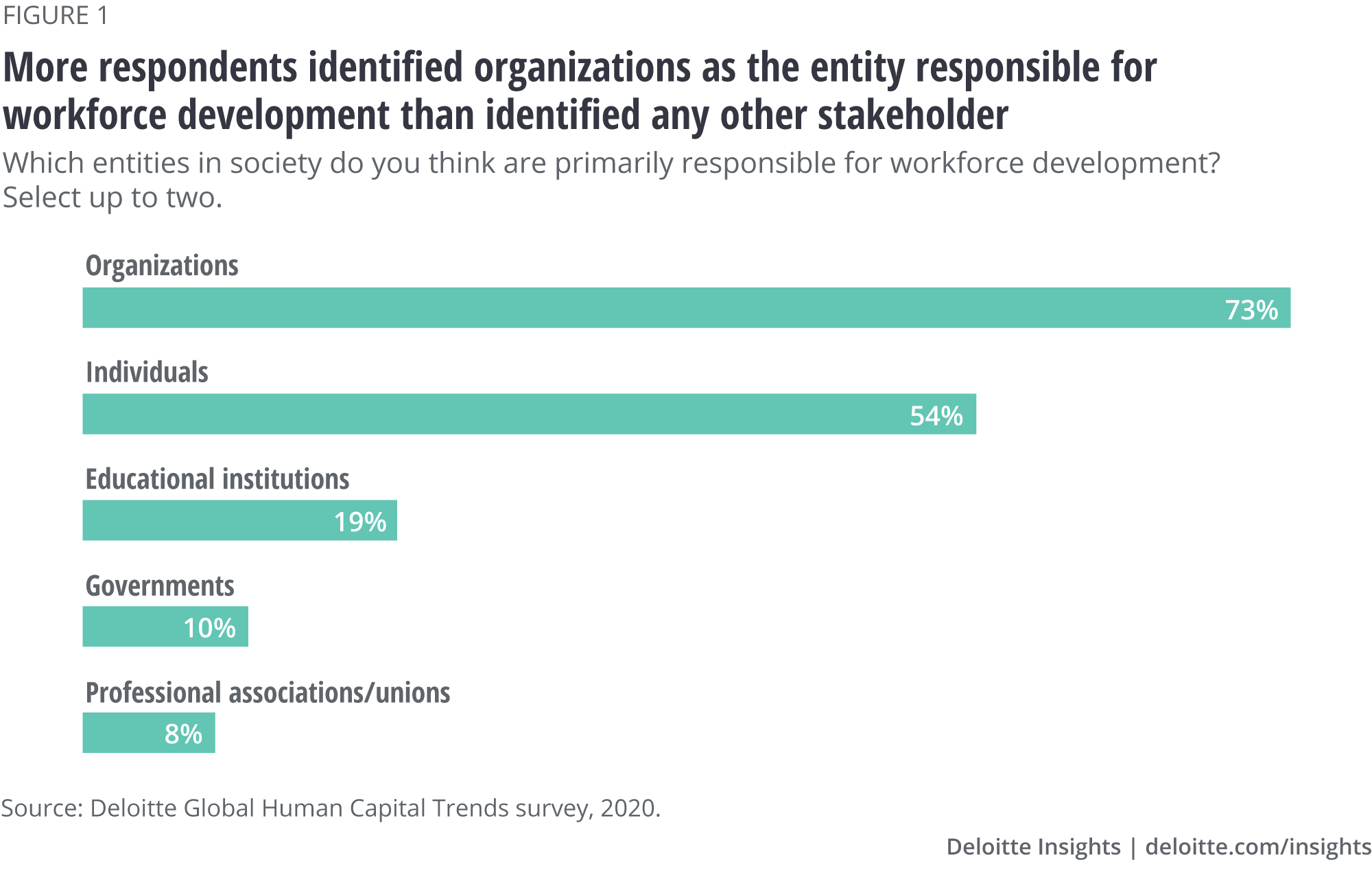

Amid this pressure to adapt their business models to capitalize on the age of imagination, organizations are also facing pressure from their workforces to help them keep their skills and capabilities up to date. Seventy-three percent of our survey respondents identified organizations as the entity in society primarily responsible for workforce development—outranking the responsibility of workers themselves, and far exceeding the deemed responsibility of educational institutions, governments, or professional associations and unions (figure 1). In light of this expectation, there is growing scrutiny and societal pressure on organizations to address workers’ long-term employability2—with the potential for significant backlash when they lay off workers after automating their jobs.

Tipping point

In the past year, the skills race has jumped into the spotlight as both a business imperative and a social expectation. Organizations including Deloitte,3 Accenture,4 IBM,5 JPMorgan Chase,6 PricewaterhouseCoopers,7 and SAP8 announced major worker skilling investments in 2019.

Perhaps the most publicized of these efforts has been Amazon’s pledge of US$700 million to upskill 100,000 of its US workers by 2025. The program reflects Amazon’s ongoing commitment to building resilience in its workforce through a variety of programs that offer opportunities for different workforce segments, technical groups, and communities. Some of the programs, including Amazon Technical Academy, Associate2Tech, and Machine Learning University, target the development of technical skills for in-demand jobs, helping to keep workers current in both the theory and application of emerging technologies. In addition, Amazon is also helping workers find adjacent or related roles in their communities. The company offers a prepaid tuition program, Career Choice, that supports fulfillment center associates looking to move into high-demand occupations. Since 2012, 25,000 workers have used this program to launch new careers in aircraft mechanics, computer-aided design, machine tool technologies, medical lab technologies, nursing, and other fields. Amazon workers who participate in the program are rewarded with an immediate pay bump and see longer-term benefits in both earnings and career mobility. The Career Choice program is also contributing to the health of the broader ecosystem by introducing new career pathways and building talent pipelines for local in-demand roles, resulting in greater local business growth, increased household incomes, and a higher average wage in local communities.9

Yet despite the expectation of organizations to do more to address skills and capabilities shortages, our survey shows that most organizations do not have the insights they need to get started. Fifty-nine percent said they need additional information to understand the readiness of their workforce to meet new demands, and 38 percent said that identifying workforce development needs and priorities is their greatest barrier to workforce development. With jobs becoming increasingly dynamic, the skills landscape is shifting drastically and rendering exercises to define needed skills of limited use and longevity. Not surprisingly, only 17 percent of our survey respondents believed that their organization could to a great extent anticipate the skills their organizations will need in three years.

Even if organizations acquire the information needed to better understand workforce development priorities, our survey shows that many organizations will face another barrier: difficulty obtaining the necessary investments. While 84 percent of respondents agreed that continual reinvention of the workforce through lifelong learning is important or very important to their development strategies, only 16 percent expect their organization to make a significant investment increase in this area over the next three years. In fact, 68 percent of our survey respondents told us that they are currently making only moderate investments in reskilling or no investment at all as it relates to AI, one of the biggest areas of reskilling required. And 32 percent of our respondents identified lack of investment as the greatest barrier to workforce development in their organization.

Given these findings, the fact that most of our respondents—75 percent—expected to source new skills and capabilities primarily by reskilling their current workforce seems unlikely to play out exactly as planned.

Our 2020 perspective

Reskilling through the years in Global Human Capital Trends

Our calls early this decade for organizations to focus on talent development have evolved into a full-blown business imperative for those hoping to survive in an age of constant disruption. In 2013, we wrote about how the talent management pendulum was swinging from recruitment to development. Our chapter on “The war to develop talent” talked about how global talent shortages, escalating turnover costs, and workers’ desire for lifelong development were putting a spotlight on how organizations designed talent networks, planned for workforce development, built learning programs, and developed leaders. By 2014, workforce capability was becoming an increasingly more critical issue, with 75 percent of our survey respondents rating it as urgent or important, but only 15 percent believing they were ready to address it. In “The quest for workforce capability,” we called attention to the need for organizations to create a global skills supply chain to examine expected capability gaps at all levels and develop workforce capabilities using a systematic, continuous process rather than as a “one and done” annual event. We reaffirmed that theme in our 2015 and 2016 reports, which focused on learning as a key vehicle for organizations to obtain badly needed skills. By 2017, a trend was emerging that would define the late decade of reskilling: the declining half-life of skills. In “Careers and learning: Real time, all the time,” we wrote that “the concept of career is being shaken to its core” by the simultaneous increase in the length of careers and the decline in the half-life of skills. This dichotomy between the length and dynamic nature of jobs has continued to sharpen, leading us to ask this year’s critical question: How can organizations increase their own resilience and their workers’ resilience in the face of constant change?

How can organizations find a way to navigate this radically changing business and skills environment? We suggest an approach that treats workforce development as a strategy for building worker and organizational resilience—equipping workers, and thus the organization, with the tools and strategies to adapt to a range of uncertain futures in addition to reskilling them for near-term needs. Through a resilience lens, reinvention shifts from something that could threaten worker security to the very thing that defines it: Workers who are able to constantly renew their skills and learn new ones are those who will be most able to find employment in today’s rapidly shifting job market.

Investing in worker reinvention may feel risky to organizational leaders who worry that their newly reskilled workers will walk out the door, but that need not be the case. The effective social enterprise recognizes that key to success are the capability and viability of the workforces available to it, and its attractiveness to new workers and alumni across its entire internal and external ecosystem. An organization that helps its workers become more resilient can be an attractive employer indeed—one that is well positioned to compete for both existing and new talent.

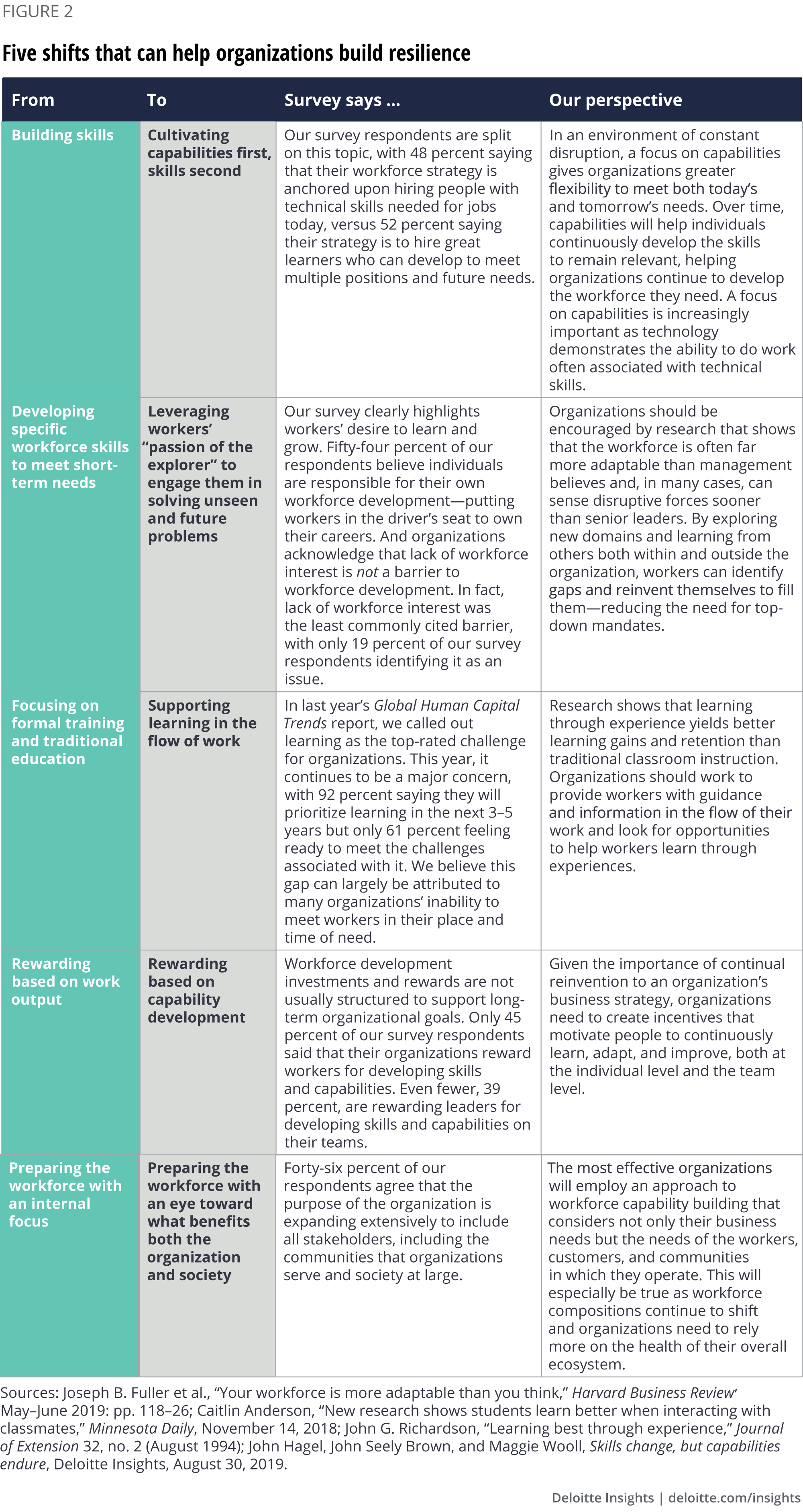

Based on this year’s Global Human Capital Trends survey, we see five areas where organizations can challenge their thinking to build resilience (figure 2). These shifts capture how organizations can think about what their workers should be learning (cultivating capabilities and engaging in unseen and future problems), how they should be learning (in the flow of work and motivated by rewards), and where they should be looking to apply what they learn (future opportunities both inside and outside the organization).

Learning by example

While not every organization may use all five of these tactics at once, some have already begun the journey to building resilience by distinguishing themselves as leaders in one or more areas.

Some organizations are shifting their focus from building skills to cultivating capabilities first. Latin American pharmaceutical company Megalabs, for instance, offers workers the opportunity to attend leadership academies to develop future-focused capabilities such as risk-taking and innovation to support leaders’ preparedness, agility, and responsiveness for the future of work.10 In another example, Banco Santander undertook a robust strategic workforce planning exercise to identify the skills the bank will need in 2025. Doing so required envisioning future roles and tasks, identifying the skills needed to execute those roles, and quantifying the future demand for each skillset by analyzing expected business and talent trends (such as the growth of digital business and the impact of AI technologies). This exercise revealed that Santander’s workforce had the strong technical skills required to meet future demand but needed to focus on building capabilities such as communication, knowledge-sharing, and resilience. Throughout this process, the involvement and collaboration of the C-suite as champions of the project was key to its success, ensuring alignment with critical business needs. The bank launched an upskilling and reskilling plan to cultivate the required skills and critical capabilities and has activated strategic levers across HR to close these gaps (mobility, alternative workforce, and ways of working). The expectation is that cultivating these capabilities will not only prepare its workforce to better serve its customers, but also transform the company’s culture and ways of working.11

American Water is piloting a leadership program to develop capabilities essential for being a leader in the “age of disruption” such as innovating, problem-solving, and leveraging diversity of thought and ideas. During the program, participants are challenged with identifying problems and collaboratively developing solutions to address issues they are facing in their daily jobs. So far, employees have been very engaged in the program and have generated several forward-thinking ideas and potential work improvements.12

Other organizations are using experiential learning to help their people learn in the flow of work. A global petrochemical company is one such example. It developed an internal repository to help surface and develop workers’ skills that were previously invisible to the organization. The repository connects employees to projects across the enterprise, allowing them to dedicate a portion of their time to new activities to build on existing skills or to develop skills in particular interest areas. Initial indications by employees in the pilot group have been very positive, especially by late-career employees who were looking for variety in their daily work.13

Organizations can reward workers for developing capabilities in a variety of ways. Some, for instance, are working with companies such as Guild Education to offer workers debt-free pathways to pursue degrees, certificates, and the option to receive school credit for on-the-job training. Guild Education connects employers to a network of educational institutions to enable workers engaged in training to earn credits toward professional certifications from nonprofit accredited universities. This allows workers who undergo training to be more successful in their current jobs while simultaneously helping them to gain a nationally recognized credential they can take anywhere. In one year at Walmart, 6,000 employees earned a total of US$17.5 million worth of college credits while paying only a little more than US$500,000.14 Guild cites a US$2.44 return on investment for every US dollar spent:15 At Chipotle, employees who participate in Guild’s education benefits program have a 90 percent higher retention rate and are more likely to be promoted.16

Finally, two organizations provide examples of how leaders can shift their approach to training from an internal focus to an external, ecosystem one. US home improvement retailer Lowe’s, for instance, is deliberately aiming to support the health of its broader ecosystem through its training program. With the growing deficit of skilled trade professionals in its industry, Lowe’s offers apprenticeship opportunities to customer-facing floor staff to help them launch careers in carpentry, plumbing, electrical, HVAC, or appliance repair. This program provides upfront tuition funding for trade skill certification, academic coaching and support, and placement support for Lowe’s nationwide contractor network.17 And in another example, Canadian bank RBC is working to grow the skills of its enterprise, community, and society. After commissioning a study that found that 4 million of the Canadians projected to enter the workforce over the next decade were not equipped with the right skills and capabilities for in-demand careers, RBC created a career tool called “Upskill” that identifies a young person’s career-relevant skills, points him or her to personalized career options, and offers customized guidance that integrates data on job demand, projected growth, automation impacts, and earning potential.

Pivoting ahead

We believe that organizations may be ill served by the currently prevalent narrow approach to reskilling, which consists largely of attempting to precisely tally current skill needs, prescribing discrete training programs to suit, and then doing it all over again once the organization’s needs change. A system that instead invests not just in workers’ near-term skill needs but also in workers’ long-term resilience, developing their capabilities as part of work and embracing a dynamic relationship with the organization’s broader ecosystem, can help build long-term organizational resilience as well. In a world where the only constant is change, supporting workers in reinventing themselves offers organizations a sustainable path forward as they aim to equip their workforces to do the work of today—and the future.

Explore the collection

-

Prologue Article5 years ago

-

Introduction Article5 years ago

-

Designing work for well-being Article5 years ago

-

Knowledge management Article5 years ago

-

The compensation conundrum Article5 years ago

-

Governing workforce strategies Article5 years ago