Radical interoperability Picking up speed to become a reality for the future of health

19 minute read

24 October 2019

- David Biel United States

Mike DeLone United States

Mike DeLone United States Wendy Gerhardt United States

Wendy Gerhardt United States Christine Chang United States

Christine Chang United States

The future of health envisions timely and relevant exchange of health and other data between consumers, physicians, health care and life sciences organizations, and new entrants. What will it take for the industry to get there?

Executive summary

Imagine a future in which clinicians, care teams, patients, and caregivers have convenient, secure access to comprehensive health information (health records, claims, cost, and data from medical devices) and treatment protocols that consider expenses and social influencers of health unique to the patient. Technology can aid in preventing disease, identifying the need to adjust medications, and delivering interventions. Continuous monitoring can lead health care organizations to personalized therapies that address unmet medical needs sooner. And the “time to failure” can become shorter as R&D advancements, such as a continual real-world evidence feedback loop, will make it easier to identify what therapies will work more quickly in which patients. Instead of seeking care when sick, the focus can be on cost-effective prevention and keeping people healthy longer. Payment obligations, including copays and other cost sharing, can be calculated prospectively. Consumers filling out the same information in 10 different forms should be a distant memory.

Learn more

Explore the Future of Health

Learn more about radical interoperability

Attend a Dbriefs webcast

Subscribe to receive the latest insights

Download the Deloitte Insights and Dow Jones app

One fundamental enabler of this vision is radically interoperable data. The future of health envisions timely and relevant health and other data flowing between consumers, today’s health care incumbents, and new entrants. This requires the cooperation of the entire industry, including hospitals, physicians, health plans, technology companies, medical device companies, pharma companies, and consumers. When will the industry start accelerating from today’s silos to this future? Our research suggests that despite a long journey ahead, radical interoperability is picking up speed and moving from aspiration to reality.

In spring 2019, the Deloitte Center for Health Solutions surveyed 100 technology executives at health systems, health plans, biopharma companies, and medtech companies and interviewed another 21 experts to understand the state of interoperability today.

Here’s what the executives say about the drivers of interoperability and which areas of health care will likely benefit most from it:

- The biggest drivers in the industry for broader interoperability include value-based care (51 percent) and regulations (47 percent), according to survey respondents. Interviewees also pointed to consumer demand as a driver.

- Cost of care (44 percent), consumer experience (38 percent), and care coordination and patient outcomes (36 percent) will benefit the most from broader industry interoperability in the next three years, according to survey respondents.

Executives also say that technology capabilities in health care are accelerating rapidly; the building blocks for interoperability are nearly in place. These include resources (people) and roles with expertise in interoperability, the use of application programming interfaces (APIs), and adoption of cloud:

- Nearly 80 percent have hired data architects to define their interoperability strategies.

- Seventy-three percent have a dedicated and centralized team that oversees interoperability.

- Fifty-seven percent have established an architecture strategy for interoperability across business functions.

- Fifty-three percent are building their own APIs—either on their own or in partnership with vendors.

- Sixty percent host more than half of their applications on the cloud.

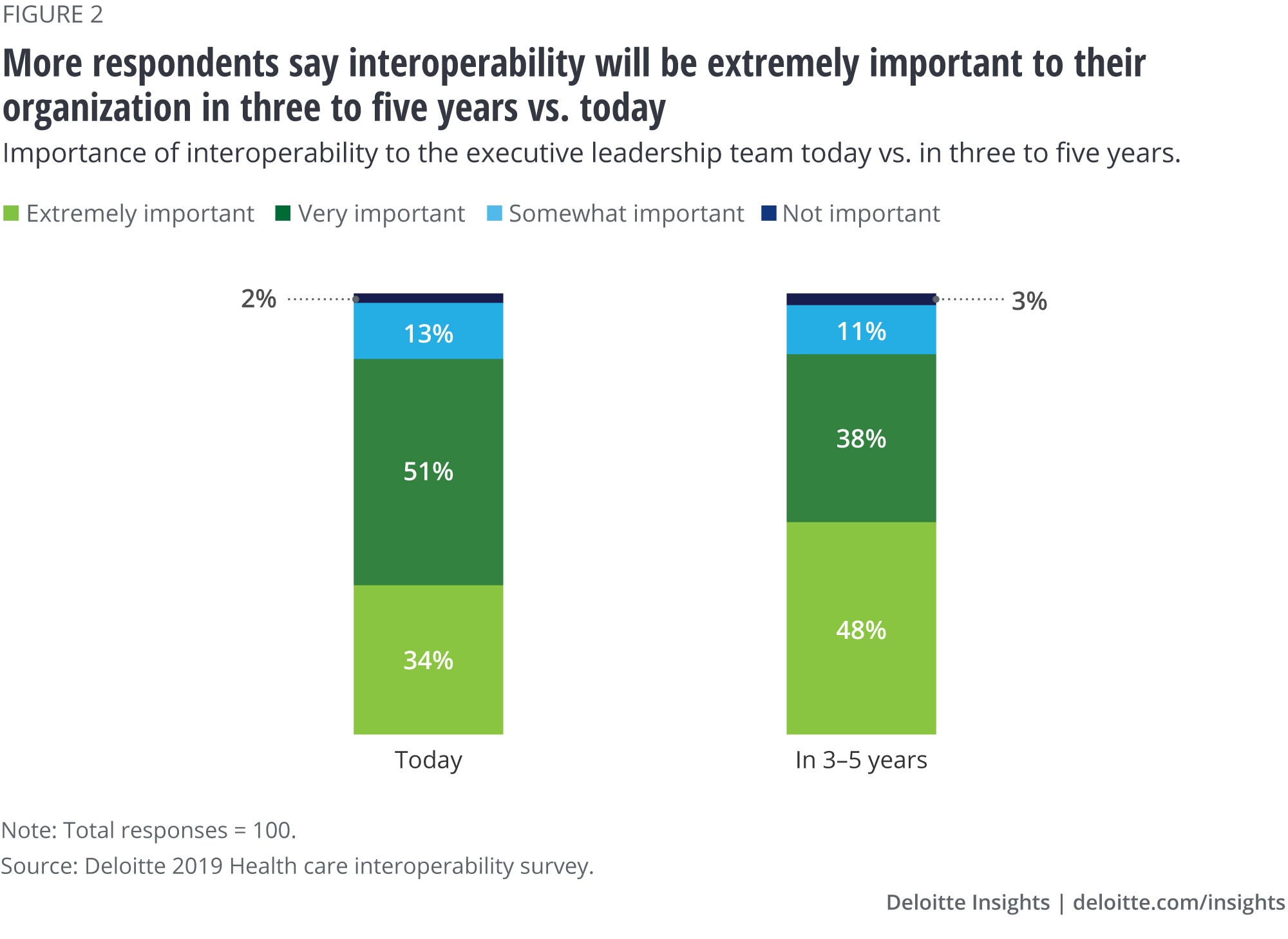

Despite agreeing that interoperability is beneficial and that the technology building blocks are available, our research findings also indicate that the business case—clear measures of ROI, business incentives—to invest in interoperability needs to catch up. More surveyed executives say interoperability will be extremely important to their organization in 3–5 years (48 percent) compared with today (34 percent). Interviewees acknowledged that it is a long journey to reach systemwide interoperability and many challenges do exist, but they believe that it will be a linchpin in the future of health.

Health care stakeholders that want to emerge as a leader in their use of data and analytics in the future of health should:

- Prioritize interoperability at the leadership level by developing a clear understanding of how important interoperability is to the organization’s overall strategy, what it will enable for the business, as well as a vision for interoperability in the future.

- Boldly invest strategically rather than tactically, by seizing the opportunity to focus on next-generation solutions and ensuring that all key business strategies (population health, M&A, value-based contracts or pricing strategies, real-world evidence, precision medicine) align with the organization’s interoperability strategy and future vision.

- Establish a competency center that is responsible for the organization’s interoperability technology stack, data and interface standards, and leading architectural practices and patterns to drive adoption, increase competencies, and accelerate value.

- Focus on interoperability in current and future partnerships. Be active, open, and curious, as there might be opportunities to collaborate differently with traditional competitors, regulators, large technology companies and startups, and community and nonprofit organizations than has been possible in the past.

- Leverage the coming compliance, privacy, and security regulations as a key catalyst to drive enterprise momentum. Organizations that seek to leapfrog their interoperability capability can use these opportunities strategically to create momentum, visibility, and competency within their organization.

Introduction

Radical interoperability suggests that all relevant data about people—health and otherwise—will be integrated and available for both research and action. We envision a future where health care shifts to focus on health and wellness; consumers and data are at the center; and technology is pervasive, as described in our recent paper on the future of health.

Defining interoperability

Interoperability includes:

- Integration of internal data platforms, people, and processes in such a way that the data is actionable

- Seamless and timely external exchange that improves transitions of care and enables cost transparency, early detection, and precision therapies

- Streamlined access to information for health care stakeholders to improve cost, quality, outcomes, adherence, scientific discovery, and consumer experience

- Access to and insights from health data—such as clinical, claims, scientific discovery, and device monitoring data—and other data sources—like those that can impact health and that are related to social determinants of health (financial, housing, economics, etc.)

Many other industries continue to speed ahead, adopting standards and protocols for data exchange aimed solely at pleasing consumers. Meanwhile, many health care stakeholders are left wondering where to focus their limited capital and how to scale new technologies and processes, so that they are not left behind.

The Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health Act (HITECH) and Meaningful Use helped bring the health care system into the 20th century, and electronic health record (EHR) adoption is nearly ubiquitous. But today, many in health care are still struggling to agree on standards and vocabularies, data ownership, and data security. Lack of timely, complete data is a barrier to successful payment and delivery models and can make health care inefficient at best. The industry is seeing increased demand for drug-device therapies, faster scientific discovery, and real-world evidence, but these could benefit from greater interoperability.

“Meaningful use got the car in the driveway. But it didn’t get the cars on the highway or even on the street.”—Health care informatics expert

The Deloitte Center for Health Solutions conducted research to understand the state of interoperability today in the industry (see the sidebar, “Research methodology”). We learned what the industry believes will be the largest drivers of interoperability in the future and what it considers to be the biggest challenges and benefits to greater interoperability.

Research methodology

The Deloitte Center for Health Solutions surveyed 100 technology executives in spring 2019. They included technology, data, and analytics leaders at health systems, health plans, biopharma, and medtech companies, nearly all of which earned an annual revenue of at least US$1 billion. We sought to understand the current state of interoperability across the industry and what it will take to improve interoperability in the future.

We also conducted 21 interviews to explore these topics in greater depth. Interviewees included leaders at health systems, health plans, biopharma and medtech companies, regulators, associations, policy think tanks, health information exchanges, and health technology vendors.

Research findings: Industry readiness and technology are accelerating interoperability

By 2040, radical interoperability will be a linchpin for the health care industry. What evidence do we see today that points to this vision? Where are leading companies—whether traditional health care organizations or innovative retail and technology companies—placing their bets? And most importantly, where should health care leaders focus to be successful under the future of health?

Our research notes that interoperability is not just a technology topic. There are technical and business case—clear measures of ROI and business incentives—aspects of interoperability to consider.

“Interoperability is 20 percent technical, 80 percent economic and political.”—Former government official

The industry values interoperability

Health care stakeholders clearly see the importance of interoperability. From lowering the cost of care, improving customer experience and patient outcomes, and enabling faster access to real-world evidence, respondents say they are optimistic that interoperable platforms and data will transform nearly all aspects of the health care system (see figure 1). The potential of interoperability has been under discussion for some time. But interest is accelerating: Now, most health systems have data in EHRs. And more life sciences companies are developing pathways to incorporate patient experience back into their R&D processes. Combining those with claims data, consumer apps, imaging and lab data, monitoring devices, and other sources, many stakeholders want to start putting the data to use.

“Interoperability is the right thing to do.”—Health plan executive

Interoperability is expected to increase in importance in the next three to five years, as most executives recognize that their organization needs to exchange data externally to support their broader organizational strategies. Nearly half of surveyed executives say that interoperability will be extremely important to their organization in three to five years, compared with 34 percent today (see figure 2).

The technology is (almost) here

Executives interviewed say that the technology capabilities for interoperability are finally reaching health care. The survey findings highlight how the necessary technology components of interoperability are falling into place in health care: API adoption, use of the cloud, dedicated resources, and skilled staff.

APIs—code that enables software programs to communicate with each other easily—have been prevalent for years in other industries (such as financial services and travel) known for their consumer-centric interoperability of data. Many in the health care industry are now starting to embrace APIs. Adoption is expected to grow, particularly as the Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology (ONC) calls for standardized APIs. Fifty-three percent of survey respondents are building their own APIs, either on their own or in partnership with vendors.

Individual health care stakeholder organizations are also aligning their technology, people, and processes to prepare for broader data exchange. For example, 73 percent of surveyed respondents have a dedicated and centralized team that oversees interoperability at their organization (see figure 3). More than half have established an architecture strategy for interoperability across business functions, and nearly 80 percent have hired data and integration architects to define their interoperability strategies.

Use of the cloud—another technology component that improves interoperability efforts through its more scalable, economical, secure, and flexible capabilities—is also on the rise. Sixty percent of surveyed respondents state that more than half of their applications are on the cloud today. The shift to the cloud can also enable other tools, such as analytics and artificial intelligence (AI), to be used with greater efficiency. The University of Pittsburgh recently adopted a cloud solution to help clinicians use applications from other hospitals (see the sidebar, “University of Pittsburgh Medical Center (UPMC): Building interoperability capabilities”).

University of Pittsburgh Medical Center (UPMC): Building interoperability capabilities

UPMC is a health system that operates across more than 40 hospitals and 700 outpatient sites.1 UPMC embarked on its interoperability journey more than a decade ago, focusing first on integrating two different EHR systems. UPMC uses Epic as its ambulatory EHR and Cerner for its inpatient EHR.2 In 2006, UPMC announced that it would partner with dbMotion, which is now owned by Allscripts, to connect the two platforms.3 By 2012, two out of three providers in the system reported that they used information in dbMotion to make clinical decisions and direct course of treatment.4

More recently, UPMC invested in a cloud-based health care operating system, which allows clinicians from different hospitals to access applications built at other hospitals. This solution allows UPMC to use emerging technology, such as natural language processing, to analyze structured and unstructured data, speech, and images across its systems and deploy information straight to the clinician at the bedside.5

With the technology more broadly in place today, more than 50 percent of survey respondents say they are able to exchange data with external entities, including medical devices and consumers, and 76 percent say the data is electronically integrated into their systems. But many interviewees also say that the data is not always exchanged in a timely manner or presented in a format that fits into clinicians’ workflows (rather than see it displayed in an EHR, physicians may have to use a separate portal to check patient data). Interviewed executives are also challenged with a “fire hose” of data, particularly as more data sources become more connected. But as AI and other technologies become more widely adopted, users may be able to sort and find the most relevant piece of information at the point of care.

Health Level Seven’s (HL7) Fast Healthcare Interoperability Resources (FHIR)

HL7 is a not-for-profit organization that develops international standards for exchange of health data. In January 2019, HL7 released the fourth version of FHIR. This standard for exchanging health information electronically focuses on breaking down data into modular components and is designed specifically for web environments, and thus can work for mobile phone applications, cloud, and EHR data.6 It enables data to be retrieved by assigning it unique identifiers, allowing different applications to point to the same data.7 The industry has embraced and supported FHIR. Many interviewed executives suggested that the adoption of HL7 FHIR standards by Apple, Google, and other large technology companies will finally pressure the broader industry to adopt uniform standards.8 However, FHIR is only one piece of the interoperability solution, and there is a continued need to expand the scope of FHIR-enabled use cases. Standardization of medical vocabularies, incentives, and other barriers are outside of the scope of FHIR.

Value-based care and regulation will help accelerate movement toward interoperability

Many interviewed executives discussed how the current business case (including ROI and clear business incentives) for investing in interoperability was nascent but starting to gain momentum. There are several drivers that help build the case to acquire interoperability capabilities. Although health care stakeholders do not all have the same data access needs, they can align toward a broader vision.

Most surveyed executives say that the main drivers for greater interoperability across the industry are value-based care (51 percent) and regulations (47 percent) (see figure 4). Examples exist of interoperability enabling prevention and health (see the sidebar, “Duke Clinical Research Institute: Enabling preventive care through an EHR integrated software as a medical device app”). In interviews, executives say that consumer demand for transparency and access will also drive it, particularly among younger generations. Some interviewees say that proposed interoperability rules by the ONC and the US Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) are a move in the right direction.

Duke Clinical Research Institute: Enabling preventive care through an EHR integrated software as a medical device app9

Duke Health’s Duke Clinical Research Institute (DCRI) partnered with Cerner in 2018 to develop an EHR-integrated atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) risk calculator app. Untreated ASCVD can cause heart attacks, sudden cardiac arrest, and strokes. The open source, FHIR-based app, which could be classified as a software as a medical device (software used for medical purpose(s) that is not part of a hardware medical device10), uses information from multiple EHRs and allows physicians to track and advise their patients based on risk factors for heart disease and stroke. The app also assesses the risk and benefits of therapy options. Often these issues are not addressed during appointments. The app seeks to make prevention easier and faster and improve patient outcomes.

Many interviewed executives say they are watching large retailers and technology companies, many of which are bringing new solutions to market and intensifying the competition. More importantly, these companies may have the capital, agility, and capabilities to scale them up. We see evidence today that companies like Google, Apple, Amazon Web Services, and Microsoft are developing products aimed at doing just that (see the sidebar, “New entrants from outside the industry”).

New entrants from outside the industry

Several major consumer technology companies, including Apple, Amazon, Google, and Microsoft, offer health care solutions that promise to better connect consumers with their personal health data, and they are gaining traction in the market. In 2018, these companies publicly committed to support interoperability in health care and to advance data sharing standards. Their open source software releases, cloud-based solutions, alignment with the industry standard FHIR, and ability to scale through large technology infrastructures are helping them gain quicker traction in the industry than traditional stakeholders. Recently launched solutions include Google’s FHIR protocol buffers and Apigee Health APIx; Microsoft’s FHIR server for Azure; Cerner's FHIR integration for Apache Spark; and a serverless reference architecture for FHIR APIs on Amazon Web Services. Many interviewed executives noted these companies are making interoperability even more likely for the industry; therefore, investing in interoperability capabilities may be even more urgent for health care stakeholders.

The barriers are surmountable

HITECH and Meaningful Use laid the groundwork for the adoption of the foundational technology—EHRs. But, the technology and processes (internal and external) to exchange health data is not yet fully mature. Now stakeholders should agree upon data standards and business cases, among other factors, to help move interoperability forward.

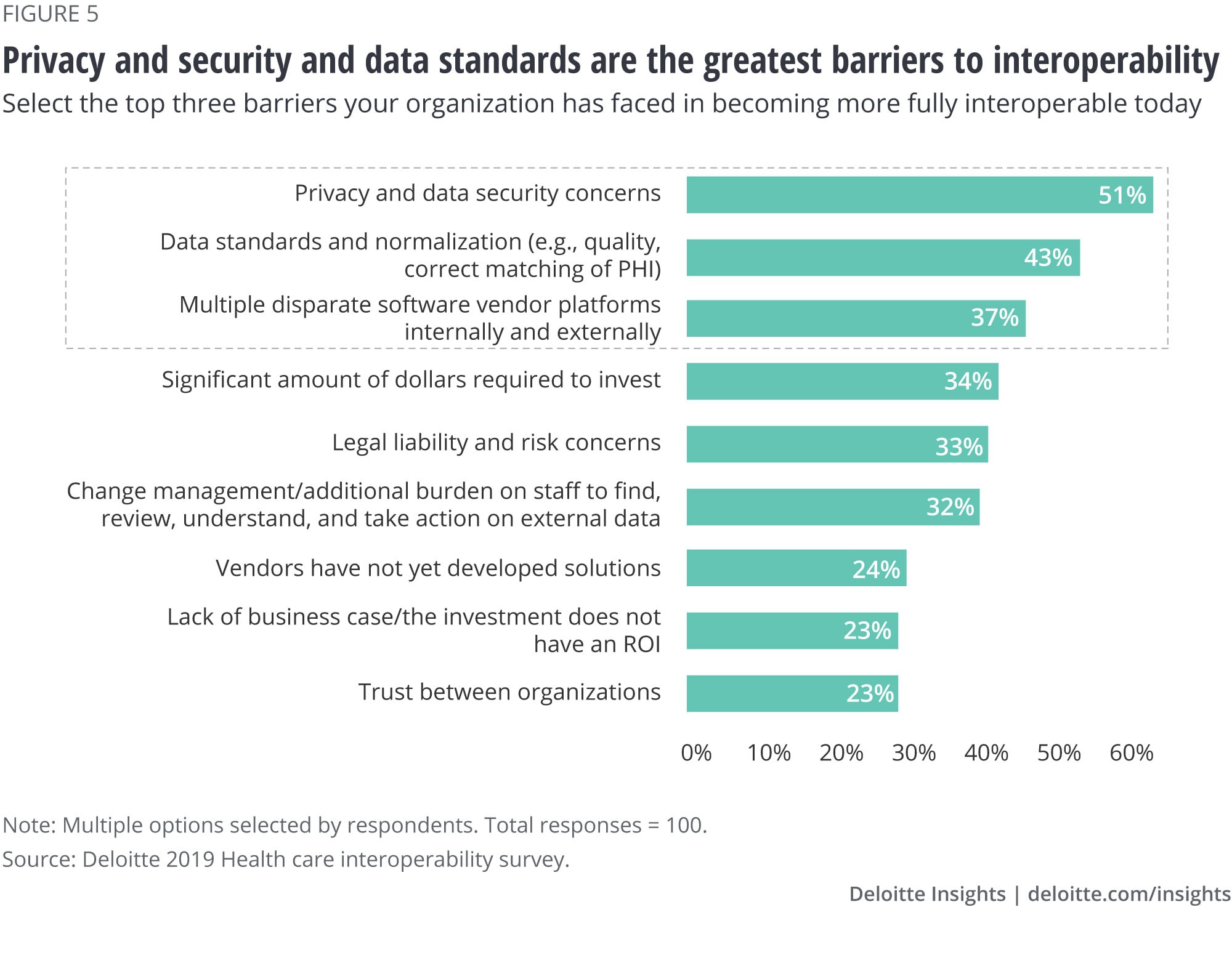

Surveyed executives say that privacy and data security are the biggest barriers to becoming more interoperable, followed by data standards, and disparate vendor platforms (see figure 5).

Many interviewed executives say that privacy and security are issues, but feel they can be overcome. These executives are more concerned about misalignment of data standards, how to define short-term returns on investment, and the lack of a national patient identifier.

Today, different organizations use different standards to define data elements. One executive said that at one point, their organization had two coders, one using the word “medicine” and the other, “medication.” The lack of even intra-organizational data standards leads executives to raise concerns about what some call “semantic interoperability.” While some say that it is okay to use multiple standards as long as they can map to each other, few are making efforts today to help map these elements.

Clinical terminology standards, Systematized Nomenclature of Medicine–Clinical Terms (SNOMED CT), and medical laboratory terminology standards, Logical Observation Identifiers Names and Codes (LOINC), are widely accepted and available to use, but adoption is not yet widespread. Many interviewed executives discussed how their EHR and other technology platforms were not originally built to align to SNOMED and LOINC. Both are slowly gaining traction and are critical aspects of seamless external data exchange.

UnitedHealthcare is also trying to tackle semantic interoperability through its partnership with the American Medical Association (see the sidebar, “UnitedHealthcare: Collaborating for interoperability and social determinants of health”).

UnitedHealthcare: Collaborating for interoperability and social determinants of health

UnitedHealthcare has partnered with the American Medical Association (AMA) to tackle semantic interoperability in an area of increasing importance to the health care industry: social determinants of health (SDOH). Using a mix of clinical data and self-reported information from patients, UnitedHealthcare and AMA will launch more than 20 International Classification of Diseases, tenth edition (ICD-10) codes to help refer patients to social and government services to address SDOH needs. UnitedHealthcare is using the success of its efforts with its Medicare Advantage population and the more than 700,000 referrals it has made since 2017 as a launching point.11

UnitedHealthcare also announced that it is rolling out a portable individual health record (IHR) to 50 million members by the end of 2019. Using Rally, its health and wellness platform that uses gamification and incentive payments to change members’ behavior, UnitedHealthcare will deliver personalized health information to members.12 The IHR, according to UnitedHealthcare’s CEO, connects to numerous EHRs and will be available to both patients and clinicians.13

While most say that interoperability is—and should be—an overarching goal for the industry, its slow pace to date has made it difficult for many to justify large investments in the short term. Moreover, few know how to measure return on investment or where to focus their investments. The move to value-based care, while gradually gaining speed, has still been much slower than many predicted.

“To make value-based care work, you need good information systems. In order to get good information systems, you need value-based care.”—Former government official

Finally, many executives say the United States needs a national identifier to enable interoperability (see the sidebar, “Patient matching poses significant challenges today”).

Patient matching poses significant challenges today

The 21st Century Cures Act required the Government Accountability Office (GAO) to study and define some of the major challenges with patient record matching. GAO found that many providers are still manually matching patients’ data and that demographic data is often inaccurate, incomplete, and/or inconsistently formatted.14 While the Social Security number is used for many purposes in addition to its original designation for the retirement security program, efforts to establish it as the official national identifier have met with considerable pushback for decades, as many cite security as a major concern. As of today, the federal government is prohibited from creating a national identification card.

What will it take to achieve greater interoperability? All stakeholders have a role.

Executives interviewed say that it is the collective responsibility of all health care stakeholders to achieve greater interoperability. Most surveyed executives say health systems (72 percent), medtech companies (71 percent), and technology vendors (71 percent) will play the biggest role in achieving interoperability. Most say that they intend to share data with health systems and physicians (62 percent), suppliers and group purchasing organizations (51 percent), and medtech companies and devices (50 percent).

Interviewed executives also say that health systems, physicians, and health plans in particular need to lead and develop organizational policies for sharing data to accelerate interoperability. Interoperability with medtech companies has also been a focus area for many, and leading medtech companies are prioritizing their devices becoming interoperable (see the sidebar, “Medtronic: Development of a fully interoperable diabetes management device”). The ONC’s Trusted Exchange Framework and Common Agreement (TEFCA) is intended to support the development of a common agreement that would help enable the nationwide exchange of electronic health information (EHI) across disparate health information networks (HINs). The intent is to scale EHI exchange nationwide. TEFCA may also rapidly accelerate interoperability with hospitals, physicians, health plans, pharma companies, medtech companies, and more.

Medtronic: Development of a fully interoperable diabetes management device 15

Medtronic is working with a nonprofit organization, Tidepool, to create an interoperable insulin pump system. Together, they are seeking FDA approval for Tidepool’s open source automated insulin delivery phone app, Loop.

This interoperable system will work by connecting the Loop app to MiniMed, Medtronic’s Bluetooth-enabled insulin pump using Bluetooth and running an algorithm every five minutes to adjust a user’s basal rate. Pairing all three components can help patients understand their glucose levels in real time, and the insulin pump will automatically infuse the insulin based on patients’ pre-defined threshold levels, helping avoid high and low blood glucose. In the future, Tidepool plans to make its app compatible with other pumps and continuous glucose monitoring devices.

An important aspect of interoperability is the exchange of data across multiple stakeholders beyond physicians. Efforts to share data with pharma companies, particularly related to improving access and outcomes of clinical research and the ability to access real-world evidence, have also been a focus area for some (see sidebar, “Pfizer and Ochsner: Creating ‘digital superhighways’ for clinical research”).

Pfizer and Ochsner: Creating “digital superhighways” for clinical research16

In 2019 Pfizer partnered with New Orleans-based Ochsner Health System to create an interoperability solution for clinical trials. The organizations will use the FHIR standard to quickly transmit data from Ochsner’s EHR system into Pfizer’s clinical trial databases. This can help Pfizer enhance recruitment to clinical trials, reduce the burden of manual data entry, decrease costs, and accelerate clinical trials. And Ochsner will be able to push out information on clinical trials to physicians to engage their patients and help them stay abreast of potential and experimental therapies for patients.

While there are several apps that use FHIR data standards for health and fitness data sharing, this is among the first use cases of data interoperability employing FHIR for clinical research, according to executives from both organizations. In the next phase of their partnership, the organizations plan to develop new ways of digitizing the entire patient and clinician experience in clinical trials, with the aim of creating a “digital superhighway” for clinical trials.

Don’t underestimate the importance of interoperability in the future

What will it take for industry stakeholders to more broadly achieve interoperability?

Future leaders of the health care industry should excel at interoperability, but many are at the starting line today. This leaves current stakeholders with the opportunity to differentiate themselves and lead in the new health economy. All strategic areas of focus for the organization can be an opportunity to bring greater interoperability and integration to the organization. Health care stakeholders should look for ways to enhance the organization’s interoperability capabilities through every initiative and strategic focus—whether it’s consumer engagement, virtual health, population health, value-based contracts, real-world evidence, precision medicine, or M&A. Taking a hard look at all factors may, in the long run, prove less costly than developing point-to-point, one-off solutions that may temporarily address a regulatory requirement, but may not fully enable an organization’s full interoperability strategy.

Health care stakeholders who want to emerge as a leader in their use of data and analytics in the future of health should:

- Prioritize interoperability at the leadership level by developing a clear understanding of how important it is to the organization’s overall strategy, what interoperability will enable for the business, and a vision for interoperability in the future.

- Boldly invest strategically rather than tactically, by seizing the opportunity to focus on next-generation solutions and ensuring that all key business strategies (population health, M&A, value-based contracts or pricing strategies, precision medicine) align with the organization’s interoperability strategy and future vision.

- Establish a competency center that is responsible for the organization’s interoperability technology stack, data and interface standards, and leading architectural practices and patterns to drive adoption, increase competencies, and accelerate value.

- Focus on interoperability in current and future partnerships. Be active, open, and curious as traditional competitors, large technology companies and startups, and community and nonprofit organizations may hold opportunities to collaborate differently than has been possible in the past.

- Leverage upcoming compliance, privacy, and security regulations as a catalyst to drive enterprise momentum. Organizations that seek to leapfrog their interoperability capability can use these opportunities strategically to create momentum, visibility, and competency within their organization.

Even organizations leading the industry in interoperability are aware that many market disrupters—ranging from consumer technology companies to startups—have entered the health care market and could potentially push interoperability to the tipping point. Understanding that these disrupters are also vying for a spot in this future will be critical, as they could be in front of the industry in the future. Organizations that are not yet thinking about interoperability strategically may find themselves lagging not only in data exchange, but also in other key strategic areas, such as value-based care.

© 2021. See Terms of Use for more information.

Explore the Future of Health

-

The future of health Collection

-

Going beyond compliance to achieve radical interoperability Article5 years ago

-

Forces of change in health care Article6 years ago

-

The health plan of tomorrow Article5 years ago

-

Smart health communities and the future of health Article5 years ago

-

The future of aging Article5 years ago