Marine plastic pollution The hefty cost of doing nothing

15 minute read

19 March 2020

Marine plastic pollution does not only have ecological ill-effects, it can also affect businesses and governments economically. The fight against plastic waste is not lost, and organizations and governments stand to save – or even gain –from taking action.

Plastic waste spewing from rivers into oceans around the world has reached an estimated 0.8-2.7 million metric tons per year.1 As the problems mounted, we all became aware of the direct consequences – the ecological impact of marine plastic pollution is well known and documented. What’s often evading attention are the financial considerations. The pollution is creating a severe economic impact on industries linked to the blue economy,2 as well as governments. There could be as much financial urgency as ecological urgency where marine plastic pollution is concerned.

Learn more

Read more on Sustainability

In a hurry? Read a brief version from Deloitte Review, issue 27

Download the issue

Learn about Deloitte’s services

Go straight to smart. Get the Deloitte Insights app

Because very few studies have explored the topic of marine plastic pollution costs, many local governments have found it difficult to assess the problem and propose solutions or alternative legislation. With this in mind, and in collaboration with The Ocean Cleanup, Deloitte developed a model to quantify the impact of marine plastic pollution in monetary terms, now and moving forward. The analysis indicated a strong economic incentive to protect rivers and oceans from plastic. Any local or central government, company, development agency or non-government organization ‘NGO’ that commits to this goal is enabling not just ecological repair but economic repair, as well as reputational benefits.

What is marine plastic pollution costing us?

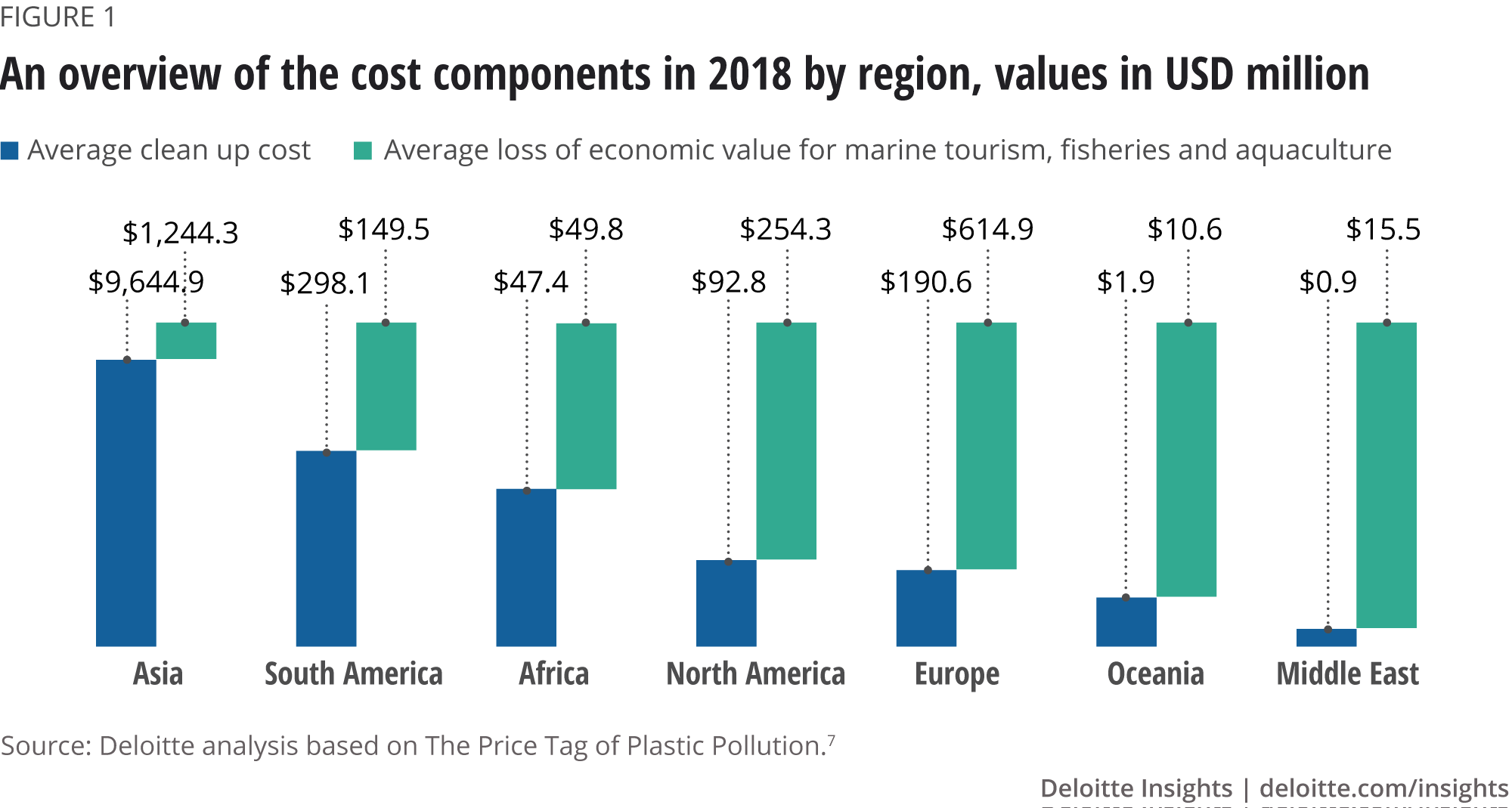

The Price Tag of Plastic Pollution model3 allowed us to estimate the annual worldwide costs associated with marine plastic pollution for 2018 in selected economic sectors. This estimated cost is up to $19 billion per year, and counting. Since it is not possible to have a single model that calculates the economic impact to the marine ecosystem, public health, and all blue economy sectors for all coastal countries, only selected economic areas (government spending for coastal cleanups, and economic loss in fisheries and acquaculture, and tourism) were included in our assessment model. Therefore, the final estimated costs and damages of marine plastic pollution are likely conservative, but no less shocking.

Plastic waste leakage

Discarded plastic waste that is not adequately managed for waste treatment can end up polluting the environment on land and in water: draining down rivers and wastewater systems, and ultimately meeting its fate in the ocean. Here, it will accumulate on shorelines, sink to the seabed or make its way to one of the five subtropical oceanic gyres. After weathering and degrading over time, the plastic disintegrates into microplastics that are nearly impossible to recover.

The model focuses on the quantitative aspect of the price tag of land-sourced marine plastic pollution in 87 (coastal) countries – what can be considered direct costs, or economic costs derived directly from damage to an industry or costs linked to an activity. The highest costs generally arise from cleanup activities, which relate directly to government spending.

Because government-sanctioned cleanup activities are typically systematic, with dedicated budgets, we deemed governments the primary orchestrators of cleanup activities and the bearers of associated costs. With the scope of our analysis limited to selected coastal countries, we identified four primary cleanup areas: coastlines, rivers/other waterways, marinas and ports. According to the costs estimated by the model,4 cleaning stranded or floating plastic waste from inhabited coastal areas would have cost $5.6-15 billion in 2018. With increasing urbanization and associated use of plastic, actions to close the tap on plastic pollution should be taken; else, these costs and damage to the ecosystem are expected to only continue to rise.

The second direct cost estimated by the model5 is related to marine tourism: The industry potentially lost an estimated $0.2-2.4 billion in revenue in 2018. The aesthetic value of the environment can be greatly affected by mismanaged waste. Stranded debris can also cause injuries and long-term health concerns for humans. Whether tourists are turned off by health/safety risks or just the prospect of an unpleasant experience, a reduction in tourism activity has caused a snowball effect, and tourism-associated businesses are seeing a loss of livelihood.

The third direct cost according to the analysis is being felt by fisheries and aquaculture businesses, which are also losing revenue: $0.11-2 billion in 2018, as estimated by the model.6 The presence of plastic debris in waterbodies has an adverse effect on marine biodiversity. Not only can this affect local ecosystems and the food chain, it can harm the fishery reserves – which are typically the main source of sustenance for the fisheries sector. The degradation of water quality tends to compound the problem by creating unfavourable conditions for aquaculture. Fish larvae can have high mortality rates and are sensitive to water quality and nutrient feed. Any slip in their survival rates can result in significant economic losses for the fisheries and aquaculture industry.

These financial impacts provide evidence of the incentive to remove river plastic. The public and private sectors have made some efforts, but more commitment is likely needed. There’s an opportunity for a multitude of governments and organizations to make a real difference in the marine plastic pollution problem if they can make lasting changes that address pressing problems. The economic assessment model discussed in the Deloitte paper The Price Tag of Plastic Pollution8 is a tool that can help identify which aspects of the plastic problem seem most acute, in an objective and quantitative manner. By homing in on these aspects, as described in the next section, solutions can be considered to reduce waste entering the marine environment, and stem the flow of costs attached to plastic-waste leakage.

About the model The Ocean Cleanup developed a mathematical model to estimate global emission of waste from rivers into oceans. Together with The Ocean Cleanup, Deloitte used the waste emission model to calculate the estimated economic damage of land-sourced plastic waste in 87 coastal countries in 2018. The research and economic assessment are comprehensively described in The Price Tag of Plastic Pollution, and the results have been published in an interactive visualization on The Ocean Cleanup’s website,9 where visitors can see the estimated plastic waste outflow per country and the costs linked to marine plastic waste. The model10 offers - to our knowledge - the first integral economic perspective on the problem of marine plastic pollution, consolidating existing studies and data points. It is based on approximately 3,500 data points sourced via secondary research. Indicators such as waste density and waste outflow from rivers per country are based on research and insights from The Ocean Cleanup. The model periodically measures direct costs, which are comparable and can be quantified. These costs represent the short-term and immediate financial impact to society. The cost estimates among countries are comparative so the model output can be aggregated at different levels while, at the same time, the impact can be zoomed in per capita. |

Why are we not winning the war on plastic?

To find the right solutions, it’s important to first acknowledge what is feeding the problem, both at a granular scale and from a broad perspective. In most emerging economies, domestic waste production is on the rise because of rapid urbanization,11 population growth and an increased demand for consumer goods. The waste management value chain in many economies isn’t equipped to cope with this new norm, and is often characterized by insufficient waste management, poor waste disposal and, ultimately, waste leakage. Urban areas often generate more waste than they can manage, and this situation tends to only worsen with additional economic development. Heaps of mismanaged waste tend to be left near major roads, in open spaces and close to riverbanks and shorelines, where it can find its way to the ocean.

So what measures are already in place to mitigate this situation, and why do they not seem sufficient? Globally, cautious initiatives have tried to tackle the problem at its source. Many concerned citizens, and government and non-government entities, have made efforts to intercept mismanaged waste from land-based water sources and clean up beaches. However, although active involvement of citizens could be critical if any progress is to be made, waste collection cannot likely be sustained by volunteering or sporadic activity.

Waste pickers – individuals who seek profit by recovering recyclables from waste and redeeming them for money – are principal actors in the recycling industry. In some countries they provide the only form of solid waste collection, bringing widespread public benefits and achieving high recycling rates for specific types of waste only. But unless a waste picker perceives value in an item, they typically will not be motivated to pick up that item, for example, a plastic bag. So again, we see a weakness in existing efforts: Plastic waste with low or no residual value is going uncollected and unsorted from general waste, including single-use plastics. But the problem goes far beyond collection.

Consider the sorting of waste, which is necessary to extract recyclables and process them; as it stands now, not all waste received by recyclers is recyclable. Although sorting is sometimes achieved by households (which segregate domestic waste), or by separate collection channels or mechanical sorting at dump sites, these solutions are not consistently available everywhere. The full expanse of the waste management value chain should be addressed, or we’ll likely continue to see both costs and ecological damage rise.

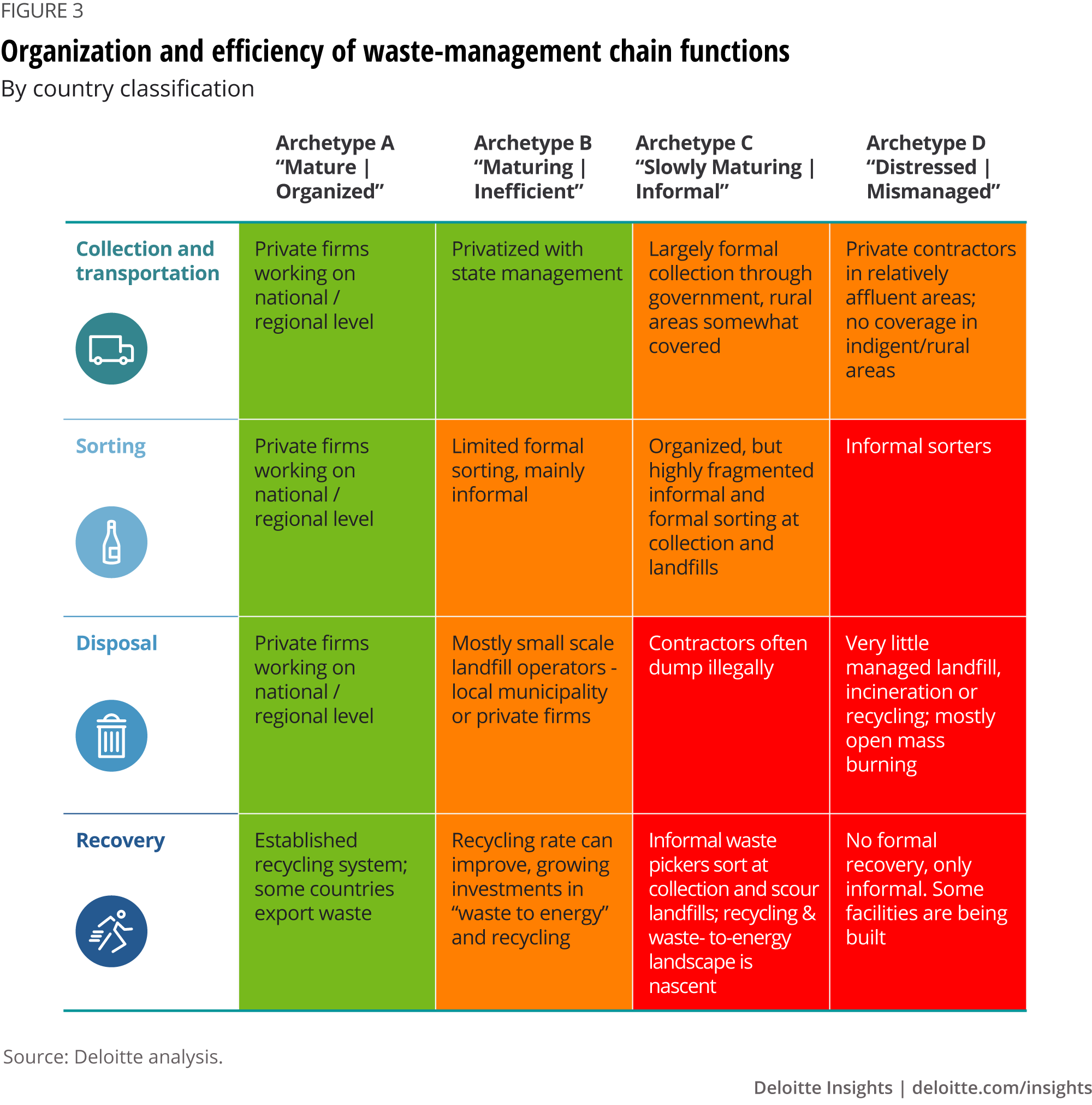

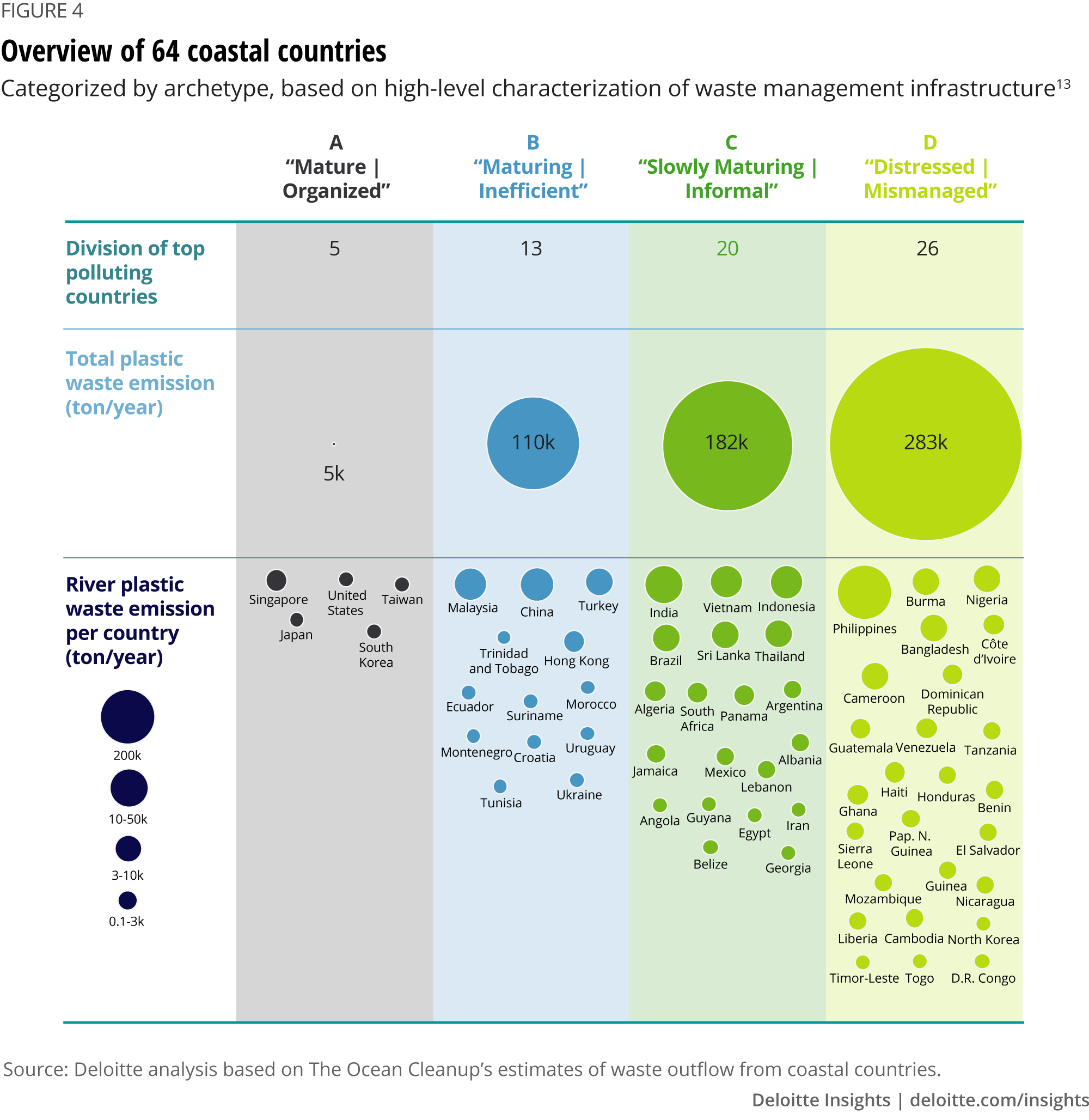

A responsible, well-established waste management infrastructure allows waste collection, transportation, sorting and processing – ideally recycling – in a way that keeps plastic from ending up back in the river or environment. Unfortunately, this is a standard many geographies just aren’t meeting, with their systems falling short at several – or all – stages. One of the key causes to this being the severity of the pollution in affected regions. Deloitte examined data on 70 countries with the highest plastic waste emissions from rivers into oceans and identified four archetypes of waste management system maturity. We found that responsibility for almost two-thirds of the total waste emissions can be attributed to countries that sit in the “slowly maturing/informal” and “distressed/mismanaged “archetypes (figure 2).

There are opportunities for improvement across the entire waste management value chain, but arguably the biggest challenges lie in sorting, disposal and recovery. At these post-collection stages, plastic often leaks back into the environment because of inefficiency or deliberate action, or because there are inherent limitations to informal collection, such as only valuable waste being sorted. Consider also that an immature system can cause problems across country borders; significant coordination is often needed on the ground between countries, and/or between urban and rural areas, to deploy consistent waste-interception systems and mechanics across various geographies.

Adding to the problem is that the countries with the highest outflow of river plastics typically have underdeveloped and/or underfunded plastic disposal options, and substantial leakage. Based on The Ocean Cleanup’s estimates of waste density in rivers, we found that 19 Asian countries12 account for 82 per cent of global plastic waste flowing from land into oceans. The economic impact of marine plastic pollution in those countries constitutes 86 per cent of the global costs estimated in Deloitte’s study; costs arising from potential cleanup activities are the largest contributor to overall economic damage. Asia has significantly higher-than-average costs for cleanup per capita, most likely caused by high rates of waste emission into the ocean and the population density near coastal areas.

Research from The Ocean Cleanup suggests that 80 per cent of the plastic enters the ocean via 1,000 rivers, with more than half originating in five rapidly growing economies – China, Indonesia, the Philippines, Thailand and Vietnam.

From these revelations, it seems previous solutions are insufficient or non-existent in many countries. There are too many gaps in the current infrastructure, and improvements to just one aspect of a waste management system will likely not be sufficient to make a dent in the rising bill caused by plastic waste. The use of plastic-intensive consumer goods is projected to keep growing significantly over the next ten years, especially in markets where waste management systems are only just emerging.14

What can make a real difference?

Local governments often shrink from the prospect of managing multiple stages of the waste management value chain. Especially in underdeveloped and developing countries, that kind of broad orchestration is often untenable or simply undesirable financially. It can fall on other governments and organizations to extend help to these countries; if not, the economic and ecological effects of their shortcomings could be felt by all.

Forming a local coalition of stakeholders may be a good start, but not very scalable. Who can pick up the challenge of introducing new solutions, and how will they work? There could be a global mechanism that would finance local waste management systems in a coordinated manner and thereby reduce economic impact. Realistically, this would likely demand the leadership of a large, government-level body – either working through existing global organizations such as the UN or World Bank or through a new independent entity enshrined with such a charter.

Although not nearing the scale a government initiative could have, there are other entities whose on-the-ground expertise in many regions, combined with their purpose and funding, might make them poised to orchestrate multiple stages of the waste management value chain. Development agencies and NGOs are also prime candidates to join the cause, and so are corporates such as those in packaging, chemicals or fast-moving consumer goods. Consider how the reputation of a company with a poor emissions track record could improve if that company takes global and effective action to confront pollution; such a move in favour of social responsibility would please shareholders and the public alike.

Hypothetical case study: Win-win initiative of a multinational beverage company

RefreshDrink is a fictional international soft-drink and purified-water manufacturer looking to strengthen their corporate social responsibility initiatives. They are based in the US, but have long been established in 27 countries with which they have good government relationships, having expanded their bottling plants around the world in the past few decades and contributing jobs to many economies. Recently RefreshDrink published a new corporate commitment: to remove all its own plastic from society and nature after use. The first country to benefit from their efforts will be Country Z.

Country Z’s government is initially concerned about the potential cost of cleanup and the insufficiency of their own immature waste management infrastructure. But they trust their rapport with RefreshDrink enough to meet with its director of social and environmental sustainability, and are reassured by her carefully considered plan. She explains that the costs will be mostly covered by RefreshDrink, which will also act as the main orchestrator of all the various local parties who will be involved. Country Z agrees to do their part by waiving some regulatory fees and fast-tracking required permits.

RefreshDrink moves forward with the plan, installing an Interceptor to capture the plastic and trash flowing down Country Z’s main polluted river. The collected trash and plastic is ferried to the river bank, where there is a contained mini-sorting facility set up to separate out the plastics. The towing and sorting functions are run by volunteers from a local NGO, Clean River Prosperous Community, with a mission to clean up the community, and local workers are compensated partly by RefreshDrink and partly by the recovery value of plastics collected. Program management and coordination on the ground is run jointly by RefreshDrink and the NGO.

The plastics collected feed into an organized informal economy of plastics wholesalers. The wholesalers are now able to drive significant volume to a recycling facility that was set up by the government a few years ago. Transportation of the remaining trash is organized by RefreshDrink through their logistics operations: They dedicate a truck from their fleet for twice-daily runs to dispose most of it in a sanitary landfill, with landfill fees waived by the Country Z government. The rest is routed to a waste-to-energy plant set up by the government.

Within three months, a significant portion of the river has been cleared of waste, and its tour boats resume service, sparking an interest in Country Z’s river tourism that had lay dormant for several years – tourism spikes 20 per cent a year after cleanup operations commence. With the river cleanup operation running effectively, the local communities also enjoy a boost in their employment rates, and the aquaculture and fishing businesses begin to thrive again. There is much media attention given to RefreshDrink’s meaningful impact in Country Z, which significantly boosts the brand value for the company. Drinks sales also rise in the quarter following RefreshDrink’s pilot plan, and they are able to channel some of the profit into hiring more Interceptors and workers for their next countries of operation.

Many large companies have had a presence for decades in countries with a distressed waste management value chain; they are part of the problem but, most importantly, could be part of the solution. Many know how to operate successfully in these countries and interact with local governments. They can potentially achieve what governments cannot because they’re able to coordinate solutions among thousands of waste management systems globally, with significantly lesser bureaucracy. Even businesses that don’t already have an agenda to do something about marine plastic pollution – and even those that are uninvolved in marine tourism, fisheries or aquaculture – can be contenders to make a real difference in this arena.

Steps in the right direction

A floating solution to contain waste leakage

Plastic waste leakage is fueling innovation from many different sources. One technology is the solar-powered cleanup machine Interceptor, developed by Boyan Slat and operating under The Ocean Cleanup. Inspired to find a new solution for cleanup, he deployed Interceptors in rivers and the ocean to capture floating debris. This technology aims to offer the lowest-cost-per-kilogram-intercepted compared to other solutions.

Organizations like the World Economic Forum and the UN have indicated that the recycle rate of single-use plastic such as plastic packaging, bags, straws, water bottles and utensils from a takeout order is 10 to 15 per cent.15 Most of the remaining plastic ends up as waste, which is often mismanaged. Certain countries have taken legal steps to limit the use (and manufacture/import) of such plastics, including Thailand, India, and Kenya. Japan is also extending a hand to developing countries by offering funding and technical cooperation to deal with mismanaged waste. 16

For their part, the World Wildlife Fund (WWF) committed to eliminating plastic leakage into nature by 2030, and petitioned to establish a global and legally binding UN agreement to stop the leakage of plastics into oceans by 2030.17 The NGO has marine plastic initiatives particularly focused on Indonesia, Pakistan, the Philippines, Thailand, Singapore and Vietnam. The WWF extends support by engaging with governments and corporations in policy advocacy and raising awareness.

The United States Agency for International Development (USAID) is partnering with governments, businesses and civil society in an effort to reduce plastics in the world’s waters by improving waste management. The agency provides funding, technical support, training and coordination with governments. Projects include the Clean Cities, Blue Ocean (CCBO) program to improve solid waste management in urban and peri-urban settings, particularly in riverine and coastal areas. While CCBO is global in scope, the program is designed to build on previous USAID recycling programs such as the Municipal Waste Recycling Program through an initial focus on key countries in Asia and Latin America.18

There have also been actions taken by consumer- and retail-based product companies that are following an ambition toward achieving a circular economy. These companies are rolling out alternative packaging materials across their global portfolios and establishing partnerships with packaging specialists. Some illustrative examples are:19

- Dow Chemical – Ambition to achieve all packaging be reusable, recyclable, or compostable by 2030. Contributed $15 million to Circulate Capital’s Ocean Fund.

- Coca Cola – 100 per cent of packaging recyclable by 2025. Collect and recycle the equivalent of 100 per cent of its packaging by 2030.

- Nestlé committed to achieve 100 per cent recyclable or reusable packaging by 2025. Between 2020 and 2025, Nestlé aims to phase out all plastics that are not recyclable or are hard to recycle for all its products worldwide.

Unless more such commitments arise and stand steadfast alongside novel solutions, by 2025 the ocean could contain one ton of plastic for every three tons of finfish.20 Swift, effective initiatives can bring societal benefits and subsequent cost savings. In this age of climactic climate urgency, the field is wide open for potential heroes – from government to development agencies to corporates. The prospect of involvement for all seems win-win: Cut the cost of plastic waste and earn a reputation for taking action at this moment in history.

© 2021. See Terms of Use for more information.

More on Strategy & Sustainability

-

Cocreation for impact Article5 years ago

-

Trend 5: The path to decarbonization Article5 years ago

-

100 percent renewables—aspiration or destination? Article5 years ago

-

Trend 1: The social investor Article5 years ago

-

Renewables (em)power smart cities Article6 years ago