Australia Same government, same economic challenges

Australia’s economy slowed in 2018–19 due to a housing downturn and a severe drought. But economic growth is expected to pick up on the back of monetary and fiscal stimuli, which is likely to boost household income and consumer spending.

The last three months have given Australians plenty to talk about. The May federal election saw the unexpected return of the conservative coalition government. Since then, we have also seen the country’s central bank–the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA)–cut the benchmark interest rate twice to 1.00 percentage point, the lowest level on record. These two cuts–25 basis points each over consecutive months–marked the first rate change since August 2016. Surprisingly, the cuts came after an earlier period of indications from the RBA that the next move in rates would be up rather than down.

The interest rate reductions (and expectations of more to come) partly reflect the weak performance of Australia’s economy in the past 12 months.1 But more notably, the move reflects a recent judgement call by the central bank that “full employment” has shifted, or that the number of Australians willing to work or to work more hours has increased. This implies that a lower unemployment rate (than previously thought) is needed to get wages and prices rising faster.

Growth has slowed for a number of reasons. For one, the slowdown in global economic growth, resulting from the US-China trade dispute, has increased uncertainty for businesses, weighing on a potential recovery in investments at home. Also, the sizable fall in housing prices in two of Australia’s largest markets–Sydney and Melbourne–had become contagious, leading to a fall in new-building construction and weakening housing sentiment elsewhere in the country. This fall in the value of their biggest asset–housing–has made consumers increasingly wary of loosening their purse strings for other purchases. The fall in housing prices also coincided with an extended period of weak household income growth, which too is weighing on consumer spending.

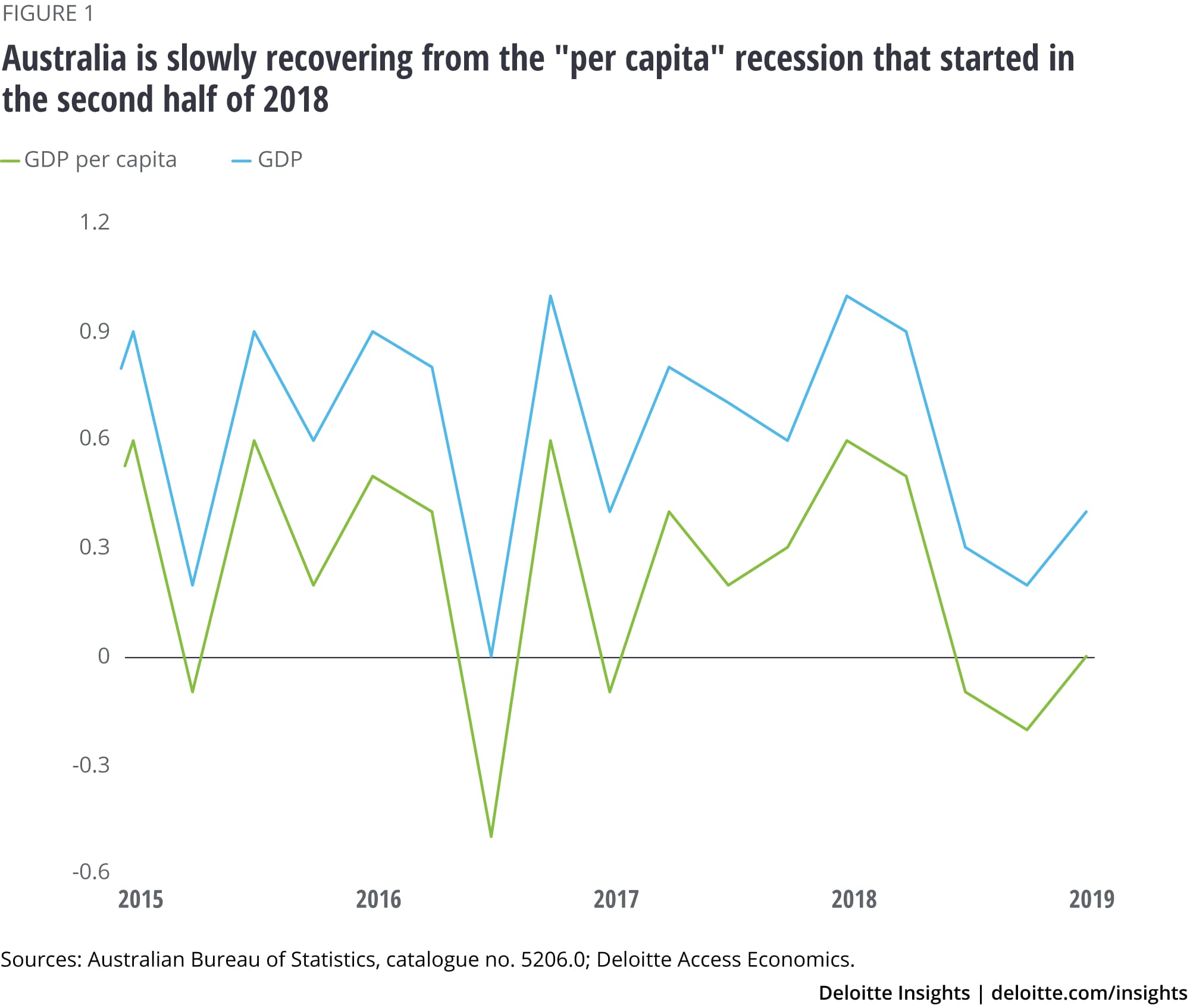

Signs of the slowing economy are particularly evident in the per person measures of economic growth. Output per person declined in two of the last three quarters, holding steady in the March 2019 quarter (see figure). Despite this, aggregate economic output is still growing at a reasonable pace due to Australia’s high rate of working-age population growth, which is particularly rapid for a developed country. Strong population growth, underpinned by migration, has contributed to the Australian economy going 28 years without a single technical recession, which is defined as two backtoback quarters of negative growth.

Better days ahead?

The good news is that the economic slowdown is not expected to last, as many of the negative factors that have been pulling down growth are starting to fade.

For one, the housing market downturn that gripped most of the country has lost steam in recent months and is expected to reverse course over the second half of 2019. This is the result of moves made by the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA) to increase access to credit for both owner-occupiers and investors; at the same time, credit has become cheaper due to interest rate cuts. As pointed out earlier, the RBA has already cut interest rates by 50 basis points, with the market expecting further cuts of 25–50 basis points over the next 12 months.2

Additionally, the return of the government has eliminated the near-term possibility of extra taxes–the partial removal of negative gearing and reduction in the capital gains tax discount to 25 per cent–being levied on income from residential properties. A section of first-home buyers will also receive a boost through the federal government’s First Home Loan Deposit Scheme.

In addition to the brighter outlook for the housing market, fiscal policy is belatedly coming to the party. Recently legislated tax cuts will result in almost five million Australians getting more than A$1,000 each in tax refunds, with another five million getting around A$500 each. Most of these will be paid out over the second half of 2019.

Tax cuts and lower mortgage repayments will help boost household disposable incomes, which should support consumer spending through the second half of 2019 and well into 2020. Further, the solid pipeline of state infrastructure spending will support project investment and employment in the construction sector, particularly across the east coast.

It is also expected that in this financial year (2019–20), mining investment will return as a source of economic growth for the first time since the peak of the mining construction boom in late 2012. This, in turn, will support business investment and the construction sector, following the peak in housing construction activity.

All said and done, the fact remains that the Australian central bank has just cut official interest rates to an all-time low–a sure sign that all’s not well with the country’s economy. While a more positive outlook for consumer spending and business investment will support economic growth over the second half of 2019 and into 2020, growth will remain relatively subdued compared to Australia’s historically high rates of economic growth.

© 2021. See Terms of Use for more information.

Explore the economics collection

-

Global Weekly Economic Update Article1 week ago

-

India economic outlook, January 2025 Article2 months ago

-

Japan economic outlook, February 2025 Article2 months ago

-

Rising corporate debt: Should we worry? Article6 years ago

-

United States Economic Forecast Q1 2025 Article3 weeks ago