Who are You When You’re Stressed? | Deloitte US has been saved

Last week was really stressful for me. I’m in the midst of several writing projects at once, nothing I would recommend, and it seemed there was also a hurricane blowing, full of other responsibilities, inquiries, requests, and demands swirling around me. You probably know how that feels.

So what did I do? I hunkered down, and spent several hours organizing my calendar–obviously–one of the more Guardian-like tasks a person can engage in. Because that’s what I do when I’m stressed.

And how about you? When you’re stressed, what do you do? Do your typical behaviors intensify? Or do you tend to act a bit out of character? Do you think your Business Chemistry type changes? Or does it get more extreme? We’re often asked by our clients just these questions. So we set out to answer them.

We asked people to complete our Business Chemistry assessment while imagining they were under stress, and 111 people did just that. Specifically, we asked people to “respond to each item as if you’re in the midst of a very stressful time. You might think back to a specific stressful time you’ve actually experienced, imagine a stressful time, or just focus in on the feeling of being under stress in general.” We then compared people’s stressed results to their original Business Chemistry results, to see if they were different.

The majority of respondents (70 percent) indicated they had recalled a specific stressful time they’d actually experienced, while 23 percent thought about being under stress in general, and just 7 percent imagined a specific stressful experience. Most respondents indicated they were thinking about looming deadlines and time pressure, critical and high profile projects involving clients and/or leadership, the need for multi-tasking, and/or a heavy work-load. In other words, they were thinking about the typical day at work for most of us.

In short, we found no evidence that any of the Business Chemistry types intensify under stress, but we did find evidence of changes in people’s behaviors and preferences.

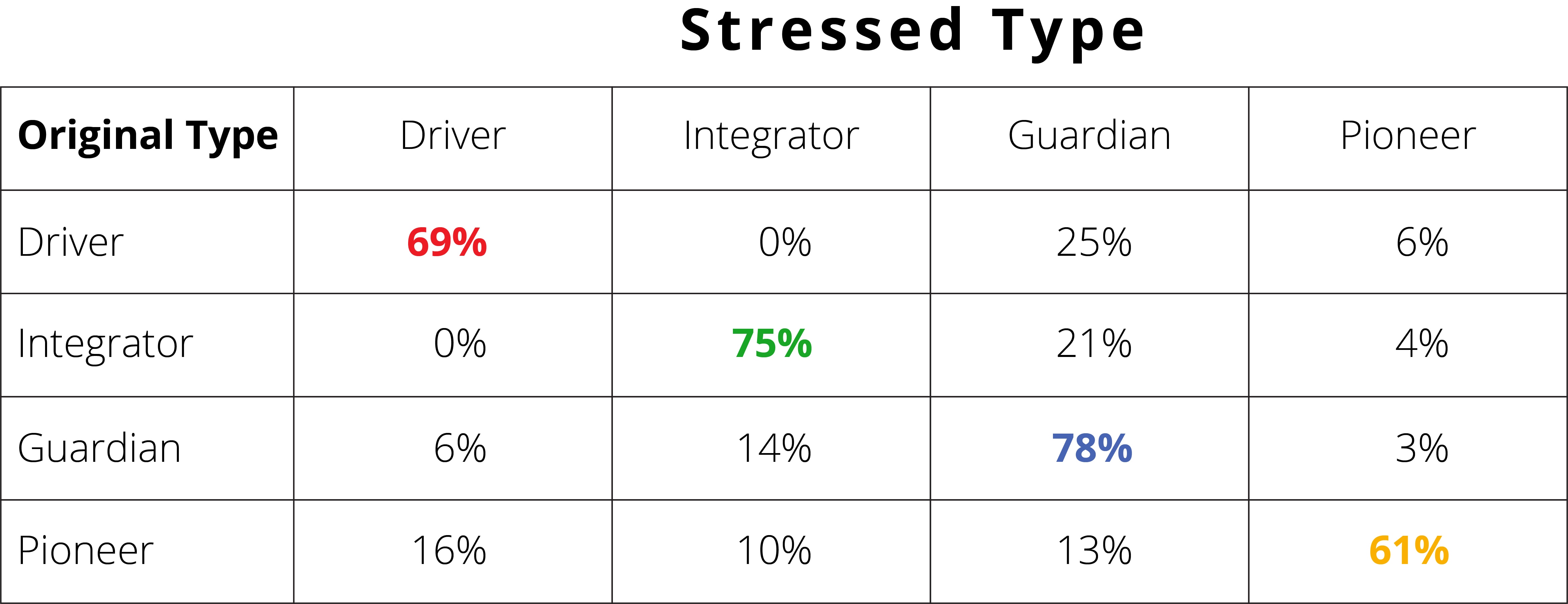

Overall, almost a third of our sample responded to the assessment items in a way that resulted in a new Business Chemistry type. Pioneers were the most likely to change–39 percent ended up with a new type–and Guardians the least, with only 22 percent changing types.

On its own, the fact that some people changed type is not terribly significant, as some number of people who take the assessment more than once will change types even without the "stress condition", particularly those whose results are not very extreme to begin with (i.e., their scores for two or more types are relatively close to one another). What's more interesting is that there are differences in how likely the various types are to change. And beyond changes in type, Pioneers also showed the greatest changes in the extent to which they demonstrated certain traits while under stress, and Guardians again changed the least.

While we found differences in the extent to which types changed, in many ways the nature of the changes exhibited under stress were similar across types. Most everyone showed evidence of becoming less optimistic and exploratory, and more risk-averse, pragmatic, and conventional. One of the reasons Guardians changed less than the other types is that they’re typically a bit less optimistic and exploratory, and a bit more risk-averse, pragmatic, and conventional, even when not under stress.

People got more scattered, too. And they also got less helpful and felt less responsibility to the broader group, while simultaneously feeling more impatient with others. Sounds like a recipe for team success if I’ve ever heard one.

Much of what we found in this study is backed up by other research suggesting that stress narrows our thinking, makes potential losses seem more threatening, interferes with logical processing, and lowers our emotional intelligence1,2. So in some ways, our findings aren’t terribly surprising. Their power, instead, is in clearing up the question of whether people’s styles intensify or change under stress. Our study comes down squarely on the side of change.

Beyond the consistent changes we saw across types, our results further suggest that under stress, people become less extreme in regard to some of the key characteristics that define their type. For example, in this sample Pioneers became less spontaneous and imaginative, Integrators became less consensus-oriented, and Guardians became less meticulous. In a way, stress seems to homogenize people, making us more similar than we are when not under stress.

This particular take on our findings may have some important implications for the cognitive diversity of our teams. We know cognitive diversity has potential benefits such as sparking innovation and mitigating Groupthink3. But if stress makes us more similar to each other, might we be losing out on some of these potential benefits at the very times when the stakes are high? And some of the ways in which we change under stress seem particularly unfortunate and harmful for teams, like becoming less helpful and more impatient with others.

Understanding how people change under stress can give you some new insight into behaviors that might otherwise be a bit baffling. Maybe your most focused team member suddenly seems all over the place. Is he stressed out? Or maybe your usually risk-embracing manager reacted negatively to a daring proposal and uncharacteristically told you to play it safe. She might be under stress.

On the other hand, if you already know you’re going through a stressful time, or a colleague is, or maybe even your whole team, watch out for these kinds of changes and talk about which ones might be appropriate. For example, maybe it’s good to pull back on risk-taking when people are really stressed. Talk too about which ones might not be so great. For example, when people start feeling less responsibility to the broader group, silos are raised and collaboration suffers. That might not be what you want.

If all else fails, when under stress you might take this advice, which I recently saw on a sign at my kick-boxing studio: Work hard and be nice.

Endnotes

1 Arnsten, A. Mazure, C.M., & Sinha, R. (2012). This is your brain in meltdown. Scientific American, May, 48-53.

2 Thompson, H.L. (2010). The stress effect: Why smart leaders make dumb decisions--and what to do about it. Josey-Bass: Can Francisco, CA.

3 Page S.E. (2007). The difference: How the power of diversity creates better groups, firms, schools, and societies. Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ.

Get in touch

Suzanne Vickberg (aka Dr. Suz)

Dr. Suz is a social-personality psychologist and a leading practitioner of Deloitte’s Business Chemistry, which Deloitte uses to guide clients as they explore how their work is shaped by the mix of individuals who make up a team. Previously serving in Deloitte’s Talent organization, since 2014 she’s been coaching leaders and teams in creating cultures that enable each member to thrive and make their best contribution. Along with her Deloitte Greenhouse colleague Kim Christfort, Suzanne co-authored the book Business Chemistry: Practical Magic for Crafting Powerful Work Relationships as well as a Harvard Business Review cover feature on the same topic. She also leads the Deloitte Greenhouse research program focused on Business Chemistry and is the primary author of the Business Chemistry blog. An “unapologetic introvert” and Business Chemistry Guardian-Dreamer, you will never-the-less often find her in front of a room, a camera, or a podcast microphone speaking about Business Chemistry or Suzanne and Kim’s second book, The Breakthrough Manifesto: Ten Principles to Spark Transformative Innovation, which digs deep into methodologies and mindsets to help obliterate barriers to change and ignite a whole new level of creative problem-solving. Suzanne is a University of Wisconsin-Madison graduate with an MBA from New York University’s Stern School of Business and a doctorate in Social-Personality Psychology from the Graduate Center at the City University of New York. She is also a professional coach, certified by the International Coaching Federation. She has lectured at Rutgers Business School and several colleges in the CUNY system, and before joining Deloitte in 2009, she gained experience in the health care and consulting fields. A mom of two teenagers, she maintains her native Minnesota roots and currently resides in New Jersey, where she volunteers for several local organizations with a focus on hunger relief.