Addressing Health Equity Through Precision Investments | Deloitte US has been saved

By David Rabinowitz, senior manager, Deloitte Consulting LLP, and Heather King, Ph.D., vice president, Impact Genome Project

The importance of addressing the drivers of health (also known as social determinants) is widely known. The vast majority of health plans and health systems (80%) regularly screen their members and patients for social and environmental factors that could negatively impact health, according to a survey conducted by the Deloitte Center for Health Solutions. However, just 35% of respondents said they have established community partnerships to address the needs identified by their members and patients. It could be that these health care stakeholders don’t know where to start. Maybe they don’t have the capacity to nurture partnerships, or lack the precision needed to drive actionable results.

Measuring what people really need to be healthy, as well as the impact and return on investment (ROI), is an ongoing challenge for programs and the organizations that help fund them. Developing a common language can help us understand which programs have the most effective strategies and the best outcomes—but it is not just a one-size-fits-all approach. This information can help funders make investment decisions that more accurately and equitably address the needs of their members or patients.

Impact Genome decodes social outcomes and strategies

Nearly two decades ago, the Human Genome Project concluded a multi-year effort to sequence and map the more than 3 billion genes that make up a human being. This information led to a common language that allowed researchers to identify genetic variants that cause disease and to develop therapies and potential cures.1 Similarly, the Impact Genome Project (IGP) has standardized more than 130 outcomes across a wide range of issues (e.g., financial health, hunger, housing, workforce development, and education). IGP used this information to build this common language that can be used across programs and research. Think of it like a Rosetta Stone for drivers of health.

IGP is a public-private research initiative that works across the private, public, and philanthropic sectors that fund nonprofits and community organizations. With this common language, IGP simplifies impact reporting for programs and helps funders understand the overall impact of their contributions. Deloitte is working with IGP to help organizations improve investment decisions and help ensure that the right resources get to the right people. The ability to address social needs upstream can dramatically reduce health costs and health inequities downstream.

Having common terms to define strategies and outcomes can make it easier for leaders to make apples-to-apples comparisons between interventions and decide where to invest. This might include benchmarks to evaluate the costs for helping someone achieve a desired outcome. For example, it might cost $8 for one person to gain immediate access to a meal (the outcome of “As-Needed Access to Meals”). IGP assesses each program’s evidence against standardized outcomes. This provides investors with a better understanding of how data is being collected and how closely it aligns to a program’s goals. IGP also surveys community needs at scale using the same language. This can help a wide range of organizations—including large employers—precisely understand what their people and their communities need to be healthy.

Applying precision investments to food security

Hunger is intricately connected to health and well-being, yet nearly a quarter of Americans report experiencing food challenges. Last year, 37% of adults received some type of food assistance from a nonprofit organization or a government service to help feed their household, according to a study from Impact Genome and The Associated Press-NORC Center for Public Affairs Research.2

Consider this: A health screener at a hospital discovers that a patient is food insecure. That information might not go beyond an entry in the patient’s medical record. The screener might provide the patient with a generic list of food pantries in the area or connect the patient to a social worker. These solutions could solve the patient’s immediate food insecurity, but it is imprecise.

We tend to lump together everything related to food security, but there are discrete outcomes that an individual can achieve, and each might require different strategies. For example, when someone is food insecure, they might have the resources to get food, but not know how to obtain healthy food within their budget. Using the IGP’s common language, this patient would identify they need “Increased Knowledge to Sustain Healthy Eating” (outcome). And to achieve that outcome, they need “Transportation” and “Healthy Meal Planning and Preparation” (strategies). Using that information, the hospital staff could then connect the patient more directly to a program that provides those exact supports. This is different than someone who does not have access to food at all, or who occasionally needs access to food. If a patient needs that outcome, providing a bag of groceries (strategy) might be most appropriate. More precisely defining patient's goals (outcomes), and how they want to achieve those goals (strategies) can help tailor the services they are offered.

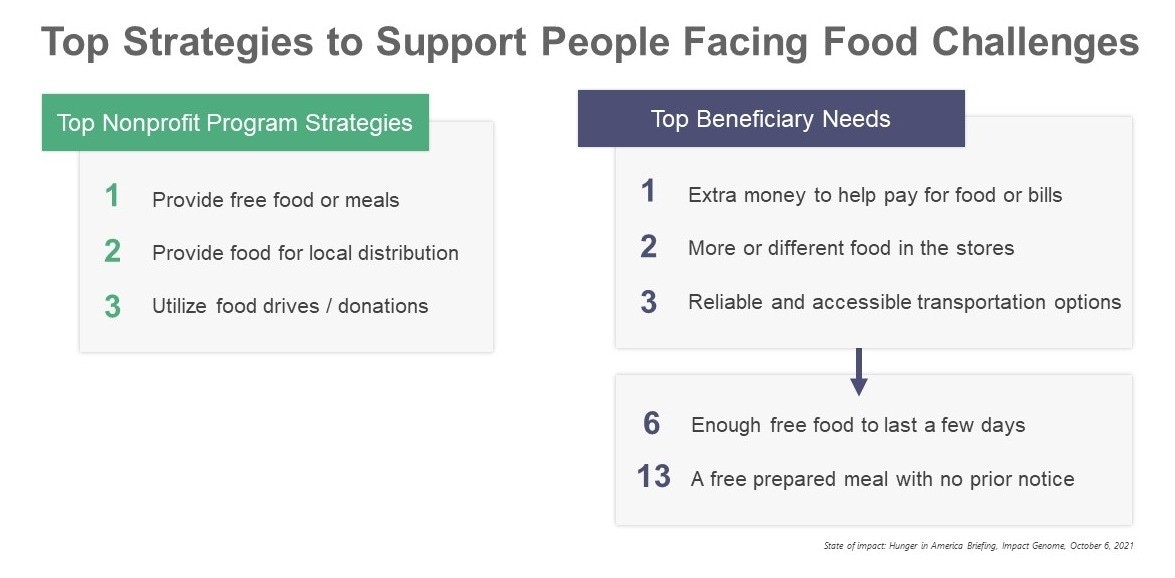

Surveying individuals with the same language that is used for program-reporting can provide insights into the types of support-programs that should be offered, and which partnerships a hospital might need to develop. For example, according to IGP’s research3, 50% of people who face food challenges say that extra money to help pay for food or bills would help address their food challenges. However, the programs most frequently used strategies focused on direct access to food. For instance, nearly 60% of programs report that providing free food or meals was one of their top five strategies.

If patients frequently report that they need extra money or transportation to help them address their food insecurity, a hospital system could then target its efforts to build partnerships with programs that have been successful in providing access to food (outcome) and in providing those supports to participants (strategy).

Health care stakeholders have long recognized that factors outside the health care system can influence an individual’s health and well-being. According to Deloitte’s survey, 69% of health plan leaders and 63% of health system leaders say they have general partnerships with local community- and/or faith-based organizations to help address the drivers of health. However, fewer than one-third of respondents are leveraging community partnerships and programs to address the specific needs of their patients, members, or the communities they service. If we all shared a common language, we might be able to more precisely invest in the social needs that contribute to health inequities.

Acknowledgements: Mackenzie Magnus, MPH/MBA, Impact Genome, LLC, Matthew Piltch and Alex Schulte, Deloitte Consulting LLP

Endnotes:

1. The Human Genome Project, National Institutes of Health, December 22, 2020

2. More than half of Americans facing food challenges struggle to get support, Associated Press/NORC, September 24, 2021

3. State of impact: Hunger in America Briefing, Impact Genome, October 6, 2021