Eurozone Slowing economic dynamics while Brexit casts its shadow

The economic recovery continues, albeit weaker than before, driven by consumer demand and labor market performance, even though risks are aplenty.

Still growing, but at a lower speed

Good news first. The eurozone economy has entered its sixth year of uninterrupted growth. The bad news is that the growth dynamics have slowed down compared to 2017. In the third and fourth quarter of 2018, the eurozone economy grew by 0.2 percent, half as fast as in the first half of the year. Among the large eurozone countries, Spain still shows the strongest performance, followed by France. While the German economy is projected to have grown slightly in the fourth quarter after it contracted in the third, Italy entered a technical recession.1 In Germany, the weakness in the third quarter was due to a drop in automotive production in response to new registration regulations.

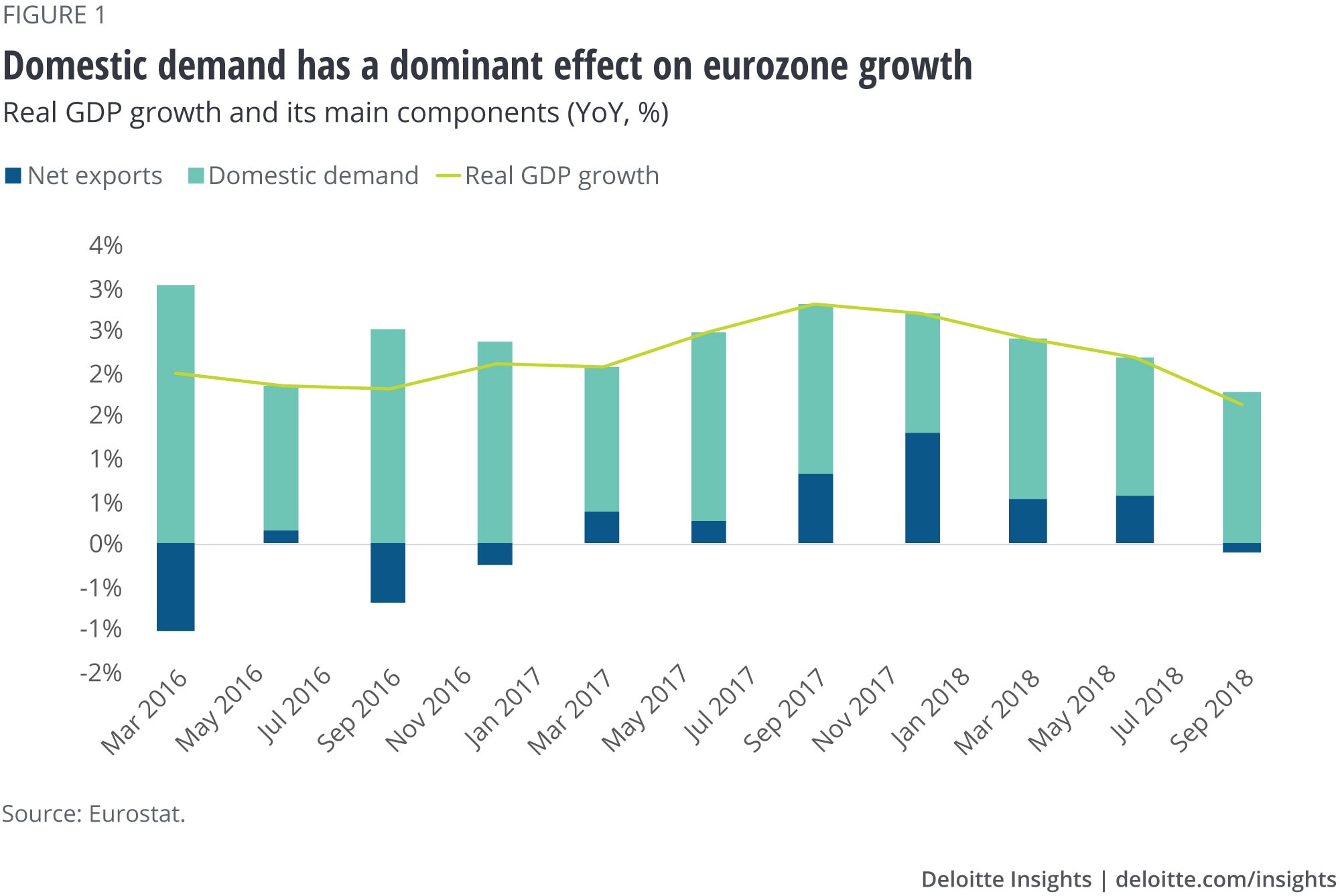

Overall, the eurozone is expected to have grown by 1.9 percent in 2018.2 The recovery continues to be demand-driven. Foreign trade made a negative contribution as imports increased and exports declined. Consumer demand and corporate investments developed solidly, although at a slower pace (figure 1).

Labor markets: Better than ever

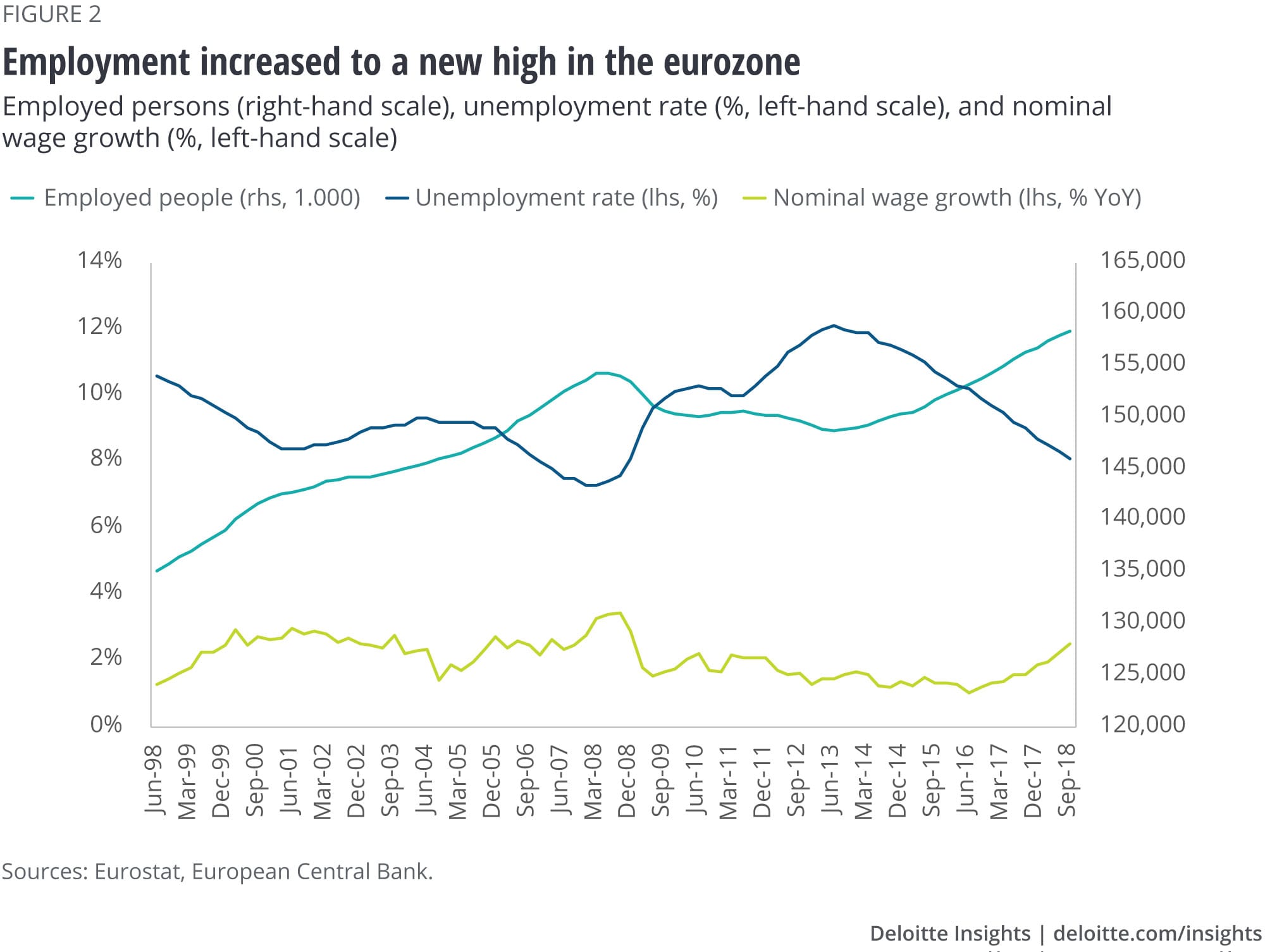

While exports and growth show significant signs of weakness, the eurozone’s labor market is a bright spot. The eurozone has reached the highest employment level in its history, while the unemployment level is down to 7.9 percent (figure 2).3 Unemployment has been on a slow but steady decline since 2014, but wages have stayed largely flat. This seems to be changing as wage growth picked up recently and reached 2.5 percent in autumn, the highest value since late 2008.4 Together with growing employment, this will likely fuel private consumption.

Sentiment: Heading south

Despite the good labor market situation, business and consumer sentiment has been worsening since end 2018. The development of several prominent early indicators underlines this.

The European Commission’s Economic Sentiment Index decreased markedly in December—the lower confidence level runs through all economic segments, ranging from industry and services to construction and consumers.5 A similar message comes from the Purchasing Managers’ Index (PMI), which dropped to 50.7 points in January.6 Not only is this a five-year low, but the PMI is now very close to the critical value of 50—values above 50 indicate accelerating economic activity and those below 50 indicate decreasing economic activity.

There are several conceivable factors for the deteriorating sentiment, some of them country-specific. The trade war between the United States and China contributes to uncertainty in the export-oriented economies of the eurozone, as do political protests in France or the debt situation in the eurozone in the context of lower economic growth.7 Whether these factors are only temporary or whether the worsening sentiment further slows down the recovery will be the crucial question in the coming months. In this context, probably the biggest risk comes from uncertainties surrounding Brexit.

The impact of Brexit on the eurozone

Brexit is supposed to take place on March 29, when the two-year period after the United Kingdom declared its exit under Article 50 expires. In January, the British Parliament rejected the withdrawal agreement between the United Kingdom and the European Union, which foresees a transition period until the end of 2020 to negotiate a new trade and political partnership.8

In principle, there are still many options on the table, ranging from postponing Brexit to a new referendum to snap elections to a revised withdrawal agreement. Nevertheless, time is running out and a hard Brexit—an exit without an agreement—remains the default option in the absence of a new plan. The disorderly exit of the United Kingdom would not leave the eurozone economies untouched.

The macroeconomic impacts on the eurozone are unevenly distributed. Model-based simulations point to GDP losses between 0.1 percent (Austria) and 1.4 percent (Ireland) in the case of a no-deal Brexit. France, Germany, Italy, and Spain would face GDP losses of 0.2 percent, according to these calculations.9

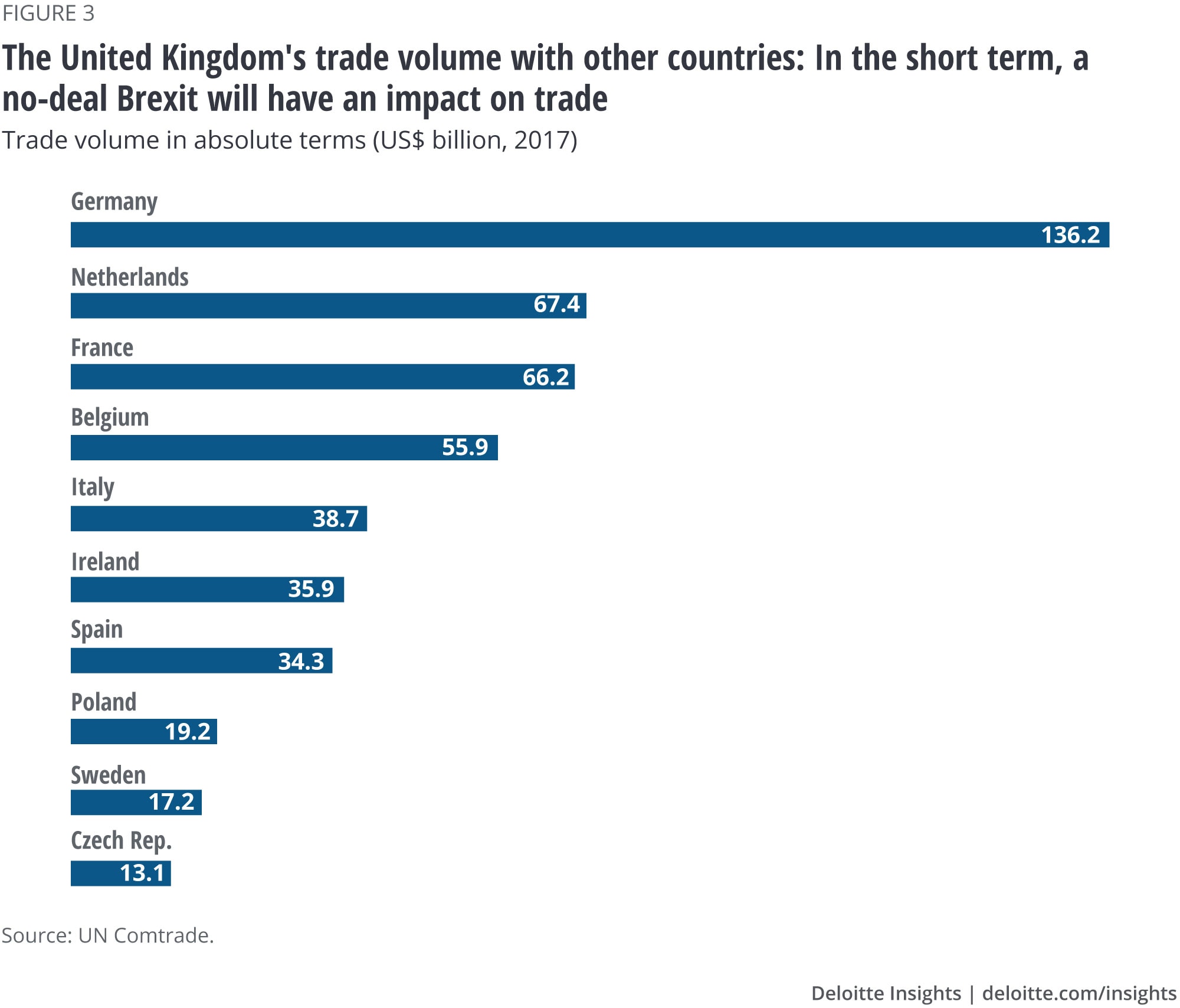

The main channel through which a no-deal Brexit would affect Europe in the short term is trade. In relative terms, Ireland has the closest links and the biggest exposure to the UK economy. In absolute terms, however, the UK-Germany trade volume is the highest, followed by UK-Netherlands, UK-France, and UK-Belgium trade volumes (figure 3).

In addition to the direct effects of a no-deal Brexit, there are also factors that could have indirect macroeconomic effects on eurozone economies, but they are hard to model. In particular, the consequences of supply chain interruptions as well as the effects of uncertainty regarding tax regulations, product regulations, and financial market reactions could have immediate effects on European companies.

Even though there is no shortage of political risks, Brexit is the biggest short-term risk for the eurozone with effects that are difficult to foresee. However, despite these risks and the worsening sentiment, the domestic drivers of the eurozone’s recovery—labor market performance and domestic demand—remain intact, while wages are finally rising. This suggests that if—and that is a big if—the political risks do not materialize and stop dragging company sentiment, there is no reason why the eurozone recovery should not continue.

Explore more economics content

-

How the financial crisis reshaped the world’s workforce Article5 years ago

-

The global economy: Set to hit the gas, yet wary of roadblocks Article6 years ago

-

Russia: Political news overshadows economic performance Article6 years ago

-

All in a day’s work—and sleep and play: How Americans spend their 24 hours Article6 years ago

-

Are we headed for a poorer United States? Article6 years ago