The homelessness paradox Why do advanced economies still have people who live on the streets?

10 minute read

25 September 2019

Homelessness exists across the developed world, and no matter how small a percentage of a country’s population is homeless, the problem is difficult to ignore, especially in modern democracies where societies are placing an increasing emphasis on well-being and inclusion.

In 2018, the world’s advanced economies—the 39 high-income economies identified by the International Monetary Fund (IMF)—boasted a per capita GDP of US$45,843 (in 2011 dollars), more than four times the corresponding figure for emerging and developing economies.1 As prosperous as they are, one might assume that everyone in these economies would have access to basic requirements such as food and shelter. Unfortunately, that isn’t the case.

Learn more

Read the related article, Addressing homelessness with data analytics

Subscribe to receive related content

Download the Deloitte Insights and Dow Jones app

Data on homelessness from key economies in the developed world suggests that not everyone even in those areas has a roof over their head.2 In the United States alone, point-in-time estimates by the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) for a single day in January 2018 put the country’s number of homeless at 552,830.3 Although this is only a fraction of the total US population (0.2 percent),4 it is a large enough number to be noticeable. And the United States isn’t alone. People sleeping on the streets or desperately seeking shelter are also seen in major cities and economies around the developed world—a puzzling phenomenon given these economies’ prosperity.

It’s hard to size the problem on a global scale

Understanding the extent of homelessness worldwide presents several challenges. For one thing, there is no single global agency that reports homelessness data; instead, several country-level organizations take stock.5 Different countries also vary in their methods of describing and tracking the problem.

First, the definition of homelessness itself differs across countries. For instance, in the United States, the HUD homelessness figures include unsheltered people as well as those in temporary shelters. In Japan, however, the definition of homelessness includes only people who are unsheltered. Canada lacks a standard definition of homelessness at all, which in turn hinders the calculation of a nationwide figure. In the United Kingdom, homelessness statistics are tracked separately in England, Wales, Northern Ireland, and Scotland, each of which has a different definition of homelessness and different metrics for measuring it.6

Second, the frequency with which homelessness data is collected and reported also differs across countries. In Ireland, homelessness data is released monthly, while other countries (including the United States) release only a single point-in-time count every year. In France, official population data comes from surveys by the National Institute of Statistics and Economic Studies (INSEE), which has conducted two surveys on homelessness to date (one in 2001 and the other in 2012). Both of these surveys, however, as in the United States, gave a single point-in-time count for the year. In Spain, on the other hand, homelessness figures are reported as an average per day. In England, homelessness reports track the number of homeless households, not people, and the definition of homelessness itself has recently changed due to the 2017 Homelessness Reduction Act.7 The country’s homelessness data now reports the number of households (and other details) who have applied for and are owed relief under the act. Earlier, statistics were made available for those who are “statutory homeless”—those who are unintentionally homeless and are a priority due to the presence of dependent children, pregnant women, etc.8

Finally, the definitions and methods used to calculate the number of homeless people have been criticized for a tendency to underestimate the phenomenon. Definitions of homelessness, for example, often exclude those who are currently housed but are at risk of homelessness. And the use of point-in-time data, critics allege, fails to capture the transitory nature of homelessness.9

Homelessness by the numbers

Even considering these challenges and criticisms, a review of homelessness data from a number of countries can offer a general picture of the problem’s extent and trajectory.

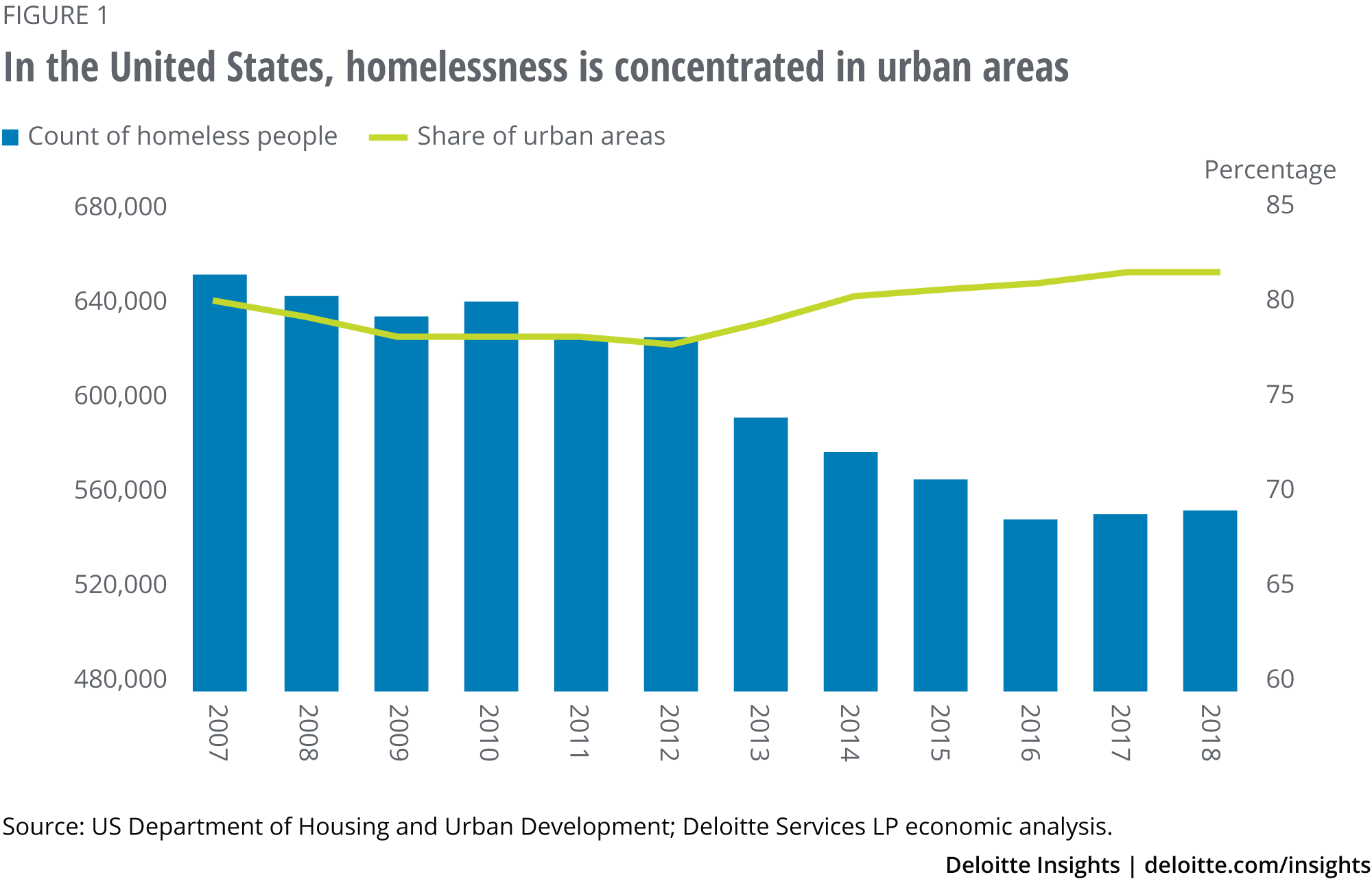

In the United States, homelessness has been on a broad downward trend since 2010, when the total number of homeless was 635,159. Over the past two years, however, the number has risen slightly—by an average of 0.7 percent each year. And while the national homelessness figures for 2019 have not yet been published, the latest data for some US cities suggests that the problem is very much alive. In Los Angeles, for example, homelessness has gone up by 16 percent in the past year, with 36,165 individuals—75 percent of them unsheltered—lacking a home as of June 2019.10

In England, due to the recent change in how homelessness is defined and measured, comparisons with years prior to 2018 is not possible. However, pre-2018 data shows that homelessness declined by 4.5 percent in 2017–2018, breaking the broad upward trend the country has experienced since 2009–2010.11 In addition, England also collects official data on those “sleeping rough”12 using single-night snapshots in the autumn of every year. This data reveals that the number of those “sleeping rough” went up by 12.9 percent per year, on average, between 2010 and 2018, with London outpacing (15.2 percent rise on average per year) the rest of the country.13

While Germany has no official federal government data on the country’s homelessness, the Federal Association for the Support of Homeless (BAG W) regularly releases estimates, which the government often uses. According to BAG W’s 2017 estimate—which was developed using an improved methodology over prior years’ estimates—Germany had 650,000 homeless individuals that year. Nearly 57 percent of these were refugees, likely reflecting the large influx of asylum seekers into Germany in recent years.14

In France, the most recent official statistics found that 141,500 people were homeless in the country in 2012, of whom two-fifths were women.15

In Italy, 50,724 people requested service assistance—a proxy for homelessness—in 2014 from one of 768 service providers in 158 cities, up by 6 percent from 2011.16 In Spain, the eurozone’s fourth-largest economy, an average of 16,437 people per day sought emergency accommodations in 2016, about 20.5 percent more than in 2014.17

In the Nordics as a whole, homelessness is less pronounced than in some other parts of Europe.18 While numbers for Sweden stand out relative to its Nordic neighbors in terms of the number of homeless—33,300 people in 2017—Finland is a success story, with the number of homeless people dropping steadily over the years.19

In Australia, which has not witnessed a recession since 1991, the number of homeless in the 2016 census was 116,427, up 13.7 percent from the 2011 census.20 In neighboring New Zealand, nearly 0.9 percent of its population or 41,207 people were homeless in 2015.21

In addition to this country-level overview, data from cities suggests that homelessness is mainly an urban phenomenon. US cities, for instance, have a disproportionate incidence of homelessness compared with more rural US locations (figure 1). In 2018, 81.7 percent of the United States’ homeless were in urban areas—with New York and Los Angeles alone accounting for 26 percent of this number.22 The situation is similar across the Atlantic. In England, where 61,410 households were owed relief under the latest statutory homelessness laws in the fourth quarter of 2018,23 nearly one-fifth of these were in London.

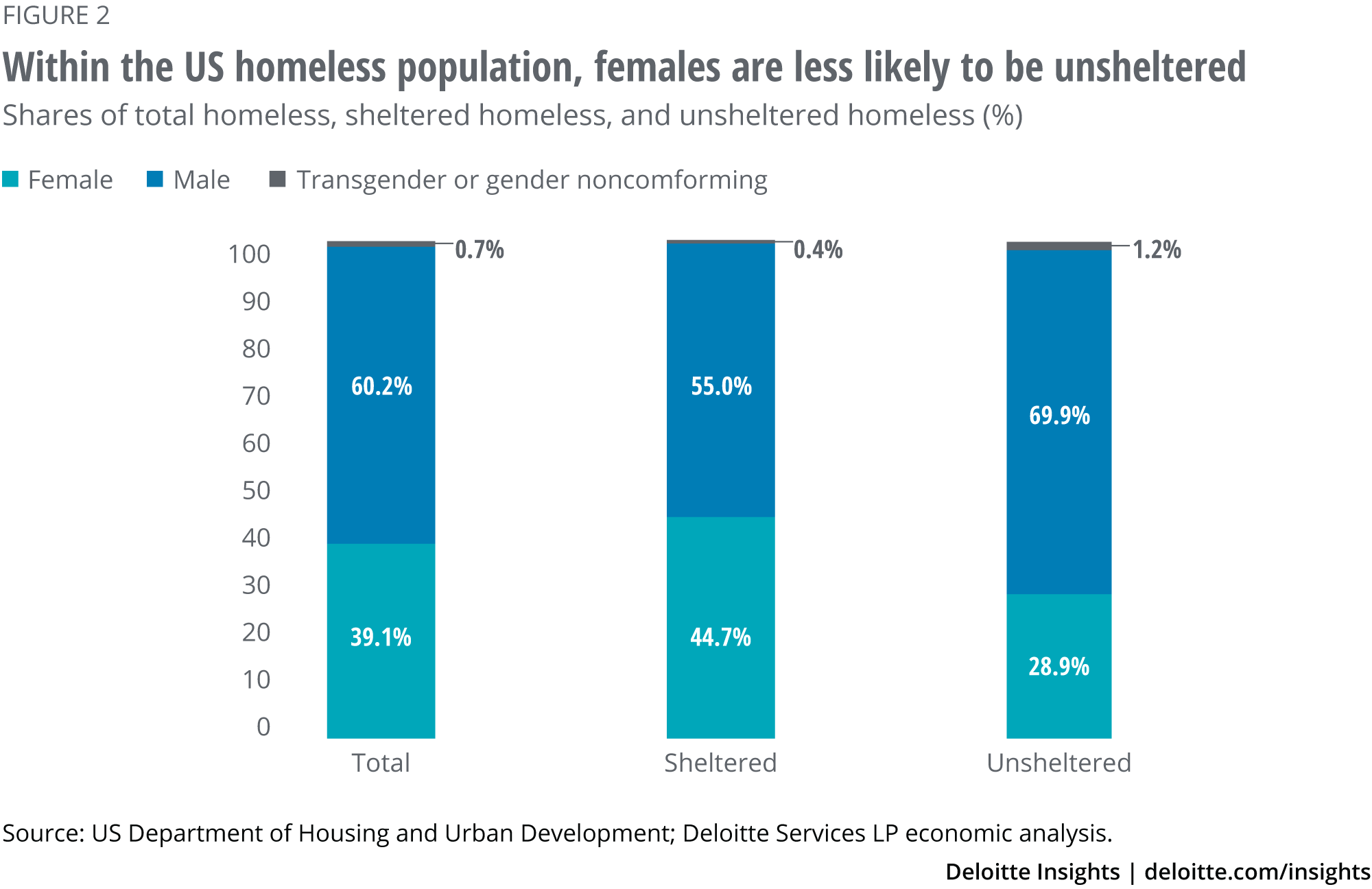

Who are the homeless? A quick look at the data from the United States and England

In the United States, 60.2 percent of homeless people in 2018 were male, 39.1 percent were female, and the rest were transgender and gender-nonconforming people.24 These percentages, however, change when we compare homeless individuals (or people experiencing homelessness as individuals) to those who are homeless in families (or people experiencing homelessness in families with children). For example, in 2018, the share of females in homeless people in families (60.6 percent) was nearly twice their share in homeless individuals. A similar pattern, though less pronounced, is evident when comparing sheltered with unsheltered homeless (figure 2): Females make up a smaller proportion of the unsheltered US homeless than in the sheltered US homeless.

The HUD data also shows homelessness by age, race, and ethnicity. In 2018, 20.2 percent of US homeless people were younger than 18 years, while those above 24 years old accounted for 71.1 percent. In the same year, 22.2 percent of the US homeless were Hispanic (by ethnicity), and 39.8 percent were African-Americans (by race). Both of these percentages are higher than the respective groups’ share of the total US population.

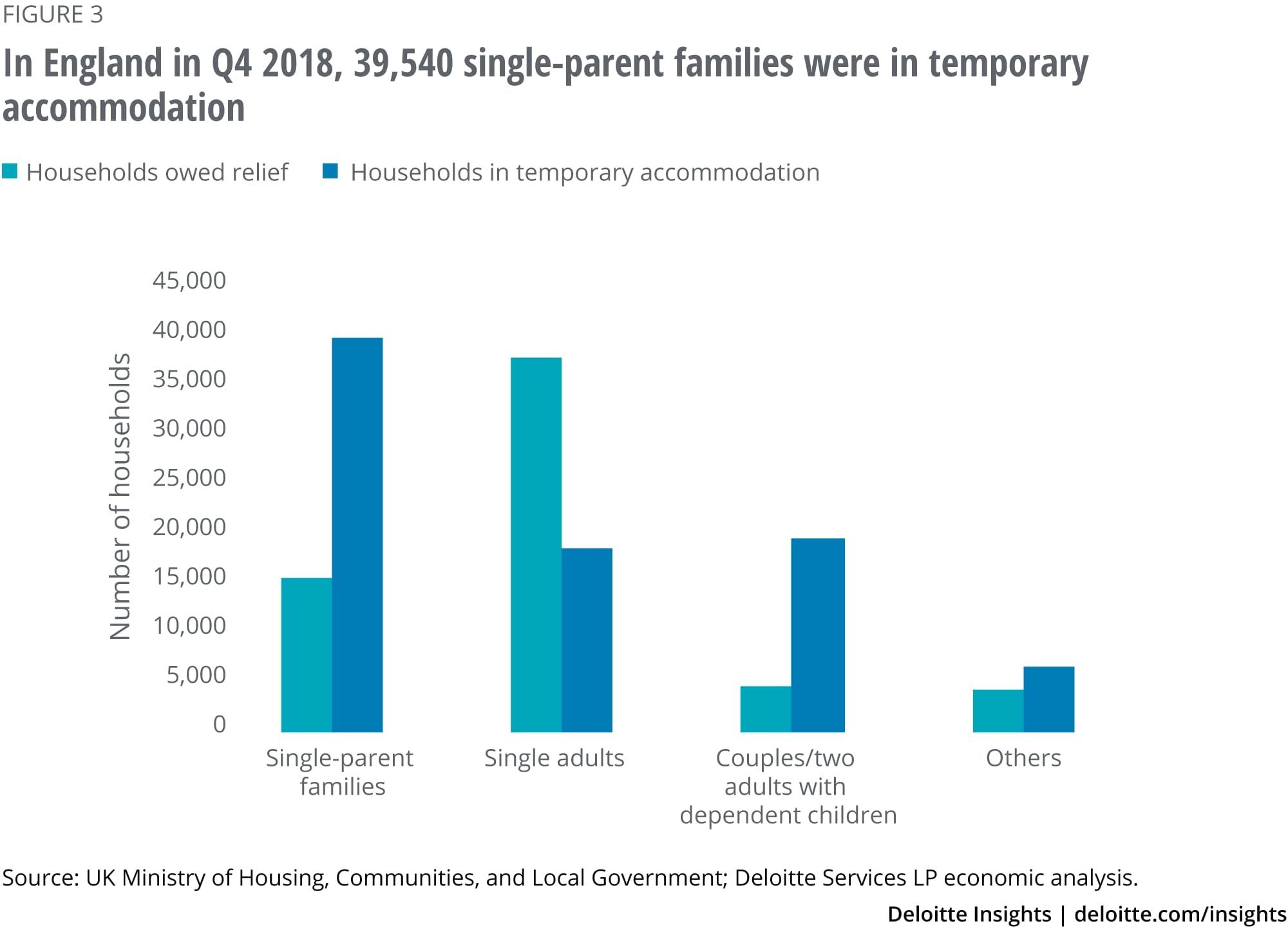

The data for England reveals interesting insights on single-parent homeless families. In Q4 2018, for example, 25 percent of the households that were owed relief under statutory homelessness duties were single-parent families with dependent children.25 However, single-parent families made up a much larger proportion (43.9 percent) of the households in temporary accommodations during this period.26 It’s the opposite for single-adult households: Single adults represented only 21.8 percent of households in temporary accommodations, while they made up 60.8 percent of the households owed relief. (Figure 3 shows a breakdown of household composition in these two groups.) One likely reason for these differences may be that families with dependent children get priority when it comes to temporary accommodation.

Homelessness has many roots

Many factors may make people, especially those at the bottom of the income and wealth ladder, more likely to slip into homelessness. Among them:

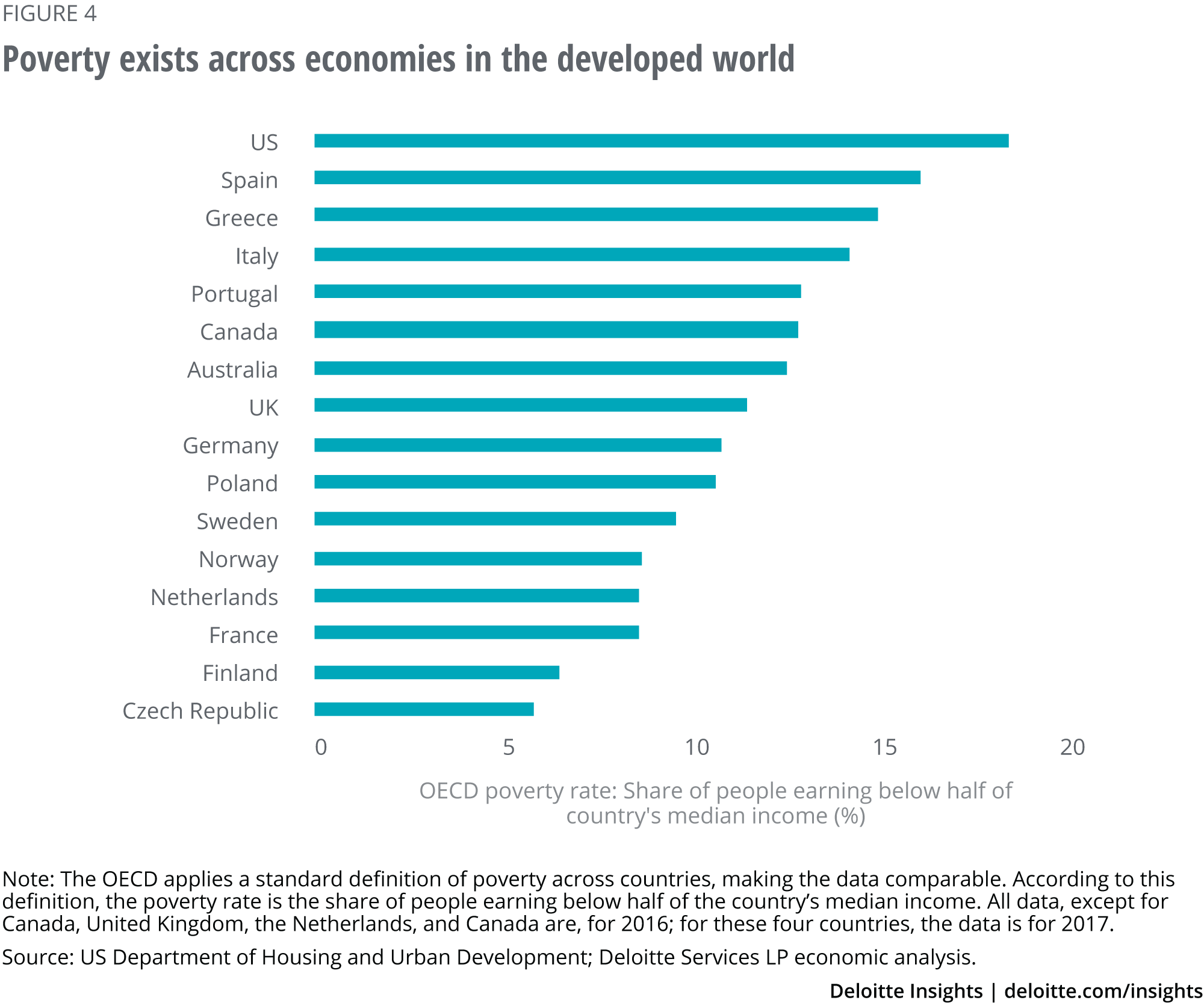

Poverty. Poor people are the most likely to fall into homelessness, especially if their incomes remain low relative to major expenditures such as housing, or if they suffer from sudden events such as job loss or an unexpected (and costly) illness. According to the US Census Bureau, 39.7 million Americans were classified as “living below the poverty line” in 2017. 27 Comparable data from the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) database on poverty shows that, across the developed world, at least some people earn less than half that of the country’s median income—a measure of poverty (figure 4).28 Figure 4 also shows that poverty differs across key economies, probably due to differing incomes across countries as well as uneven distribution of income in individual countries.

High cost of housing relative to income. People at the bottom of the income ladder spend a greater proportion of their incomes on housing compared to those in other cohorts. According to the Consumer Expenditure Survey, the bottom 20 percent of US consumers by income spent about 53 percent of their after-tax income on shelter—owned or rented—in 2017; this contrasts sharply with the mere 10.9 percent average across the total US population.29 Also worrisome is the fact that rent expenses for those in the bottom income quintile have risen more quickly (8.2 percent per year, on average) between 2010 and 2017 than have incomes (an average of 5.9 percent per year). With low-income households more likely to rent than own a house,30 the upward trend in rent expenses in recent years is troubling.

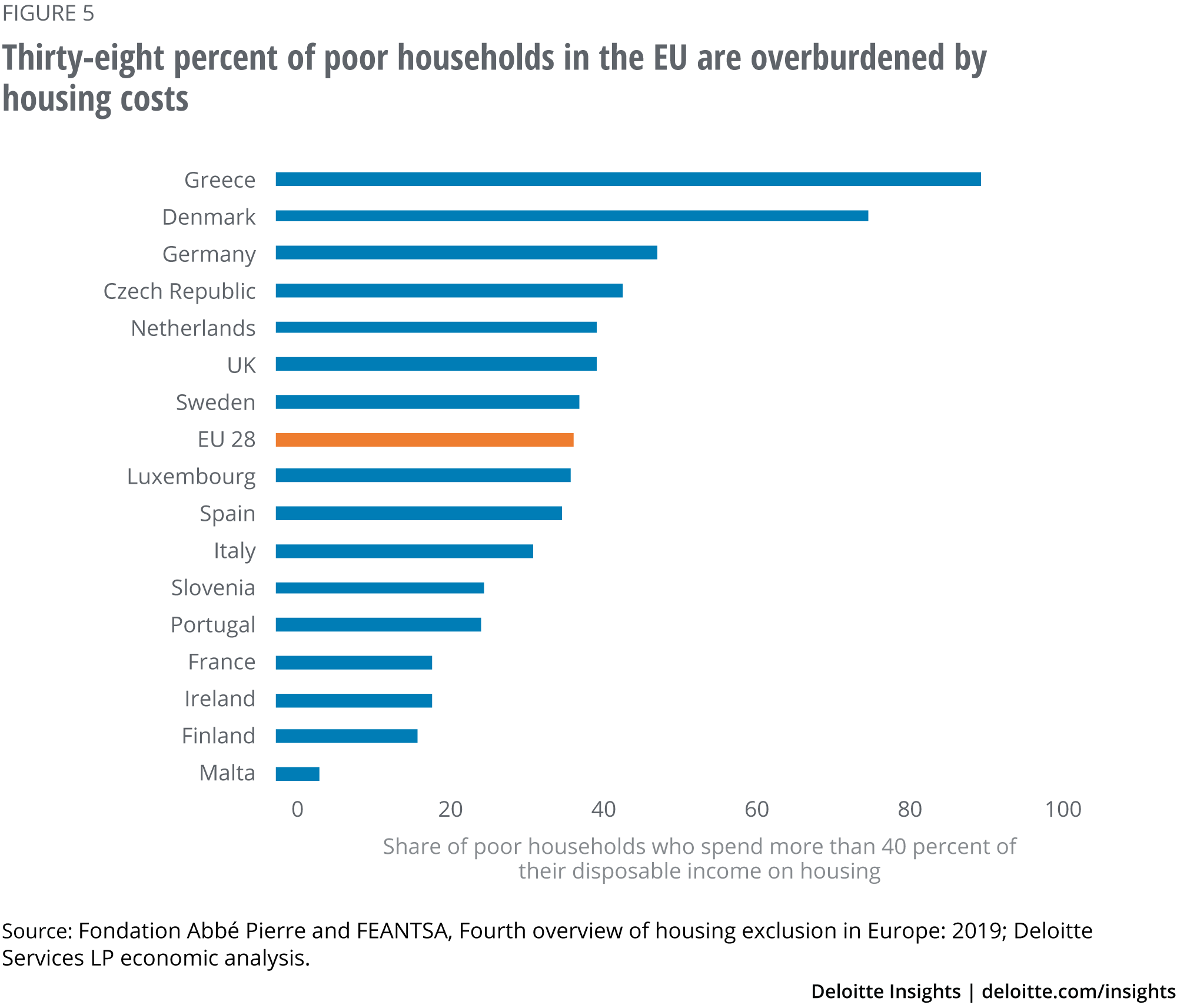

The issue of high housing costs relative to income is not confined to the United States. In the European Union (EU), 38 percent of poor households in 2017 spent more than 40 percent of their disposable income on housing31—and this share of poor households has increased between 2010 and 2017. Within the EU, the proportion of poor households who spend more than 40 percent of their income on housing varies widely, with Greece leading at 89.7 percent, and even strong economies such as Germany (48.5 percent) and the United Kingdom (40.8 percent) posting figures higher than the EU average (figure 5). Poor households are also vulnerable to being forced out of their current shelter for falling behind on rent or mortgage payments. Here again, Greece led the European Union in 2017 with 21.3 percent of its poor households falling behind, with France (16.8 percent) and Ireland (11.8 percent) coming in second and third.

Unexpected events. Not everyone has the luxury of financial security; many people live from paycheck to paycheck.32 For those at the bottom of the income ladder, an unexpected job loss, a sudden illness, a severe accident, or a natural disaster can push them into homelessness or to the brink of it. The impact is more immediate and drastic for those who earn close to minimum wage or lack family support. Research by the US Federal Reserve (Fed) reveals that only 49 percent of American households in the bottom 25 percent of the income distribution have as much as US$400 available in case of a sudden shock to income or expenses. In the United Kingdom, recently released research by the think tank Resolution Foundation suggests that lower-income households are more vulnerable to a future recession than they were in the previous one, with the increased vulnerability itself a result of the Great Recession.33

Substance abuse. While it is difficult to establish causality in the link between homelessness and substance abuse, substance abuse can make an individual more likely to lose employment and earnings and reduce his or her employability, putting them at greater risk of homelessness. In the United States, an estimated 38 percent of homeless people are dependent on alcohol, and 26 percent on other harmful chemicals.34 In Great Britain, Crisis, a charity for homeless people, found that 27 percent of its clients in 2013–2015 reported problematic use of drugs or alcohol.35 Closely related to substance abuse, too, are physical disability and mental illness. In the United States, studies suggest that as many as 80 percent of homeless veterans in the country suffer from mental health problems or substance abuse.36

Domestic violence. Domestic violence plays a major role in exacerbating homelessness. In Australia, 42 percent of those seeking assistance for homelessness in 2017–2018 reported experiencing domestic or family violence;37 seventy-eight percent of these victims were women.38 Meanwhile, in the United States, one-fourth of homeless women find themselves in that state due to domestic violence.39

Single parenthood. Single-parent families are also vulnerable to homelessness. In England, families with a single mother and dependent children accounted for almost 44 percent of the families in temporary accommodations between October and December 2018.40 In neighboring Ireland, among all the families that were homeless between April 22 and April 28, 2019, 58.1 percent were single-parent households.41 Evidence suggests that single-parent families face greater financial burdens than other household types, contributing to their risk of homelessness. In 2017, for example, 21 percent of single-parent families with dependent children in the EU spent more than 40 percent of their income on housing—compared to just 8.7 percent for all EU families.42

The need to chart a course

While countries may differ in how they define, calculate, and report homelessness data, there can be no doubt that homelessness exists across the developed world. And no matter how small a percentage of a country’s population is homeless, the problem is difficult to ignore, especially in modern democracies where societies are placing an increasing emphasis on well-being and inclusion.

So, what are developed economies to do? So far, no economy seems to have eliminated homelessness altogether. But policymakers can investigate the merits of a number of proposed solutions. One approach is a “housing first” strategy, which aims to provide homes for the homeless or those at risk for homelessness without requiring them to first solve problems related to factors such as employment, health, and family.43 A review of the workings of property markets and developing vibrant, affordable housing sectors is perhaps in order too. And in this age of the Fourth Industrial Revolution, data and digital technology can and should be used to help governments and societies address homelessness, whether by more effectively tracking its risk factors, efficiently allocating resources, or measuring and comparing intervention outcomes. See our companion report, Addressing homelessness with data analytics: A data-driven approach to homelessness, for more about how a data-driven approach can help combat homelessness.

-

Is the yield curve a modern-day Chicken Little? Article5 years ago

-

Rising corporate debt: Should we worry? Article6 years ago

-

Millennials: The overqualified workforce Article6 years ago

-

United States Economic Forecast Q1 2025 Article1 month ago

-

Retirees of the future Article5 years ago