Is the dollar too high . . . or too low? Economics Spotlight, January 2020

7 minute read

31 January 2020

The exchange rate is often the object of curiosity—is there a “right” value, what factors determine the rate, and what might it be telling us. To understand how a key global currency such as the dollar is performing, one needs to remember that conditions in both countries matter.

The idea that there is a “right” value for an exchange rate seems obvious—except to economists. The exchange rate is just a price, and, to economists, the “right” price is the one that clears the market, so that supply equals demand. The market for foreign exchange is the largest and most liquid in the world, and it clears every day. So obviously, today’s exchange rate—whatever is it—is “right.”

Learn more

Explore the Economics collection

Learn about Deloitte’s services

Go straight to smart. Get the Deloitte Insights app

But there’s more to it than that. The exchange rate is a financial price, just like the price of stocks. In the short term, it’s probably useless to try to understand or predict movements in the exchange rate. But in the longer term, observers—and anybody who uses the foreign exchange market—need to understand just what the exchange rate might be telling us.

The exchange rate is, in fact, one of the more difficult economic variables to understand. That’s because it is, in effect, two prices. A German traveling to New York wants to know the price of the dollars she will need to ride the subway. But an American traveling to Berlin wants to know the price of the euros he will need in order to ride the S-Bahn.1 Of course, these are simply the reciprocal of each other: If a dollar costs 0.80 euros, a euro will cost US$1.20. But what determines the exchange rate are the conditions in both economies: the interest rate in Europe and in the United States, the price level in Europe and the United States, and political risk in Europe and in the United States. That makes things tricky. Everything can be stable in Europe—but Europeans might see a significant change in their exchange rate solely because of events in the United States.

Because “fundamentals” involve the currencies of two countries, it’s easy to misinterpret exchange rate movements. Sometimes a country experiences an appreciation or depreciation that has nothing to do with its own affairs. Indeed, that’s not uncommon for the US dollar.

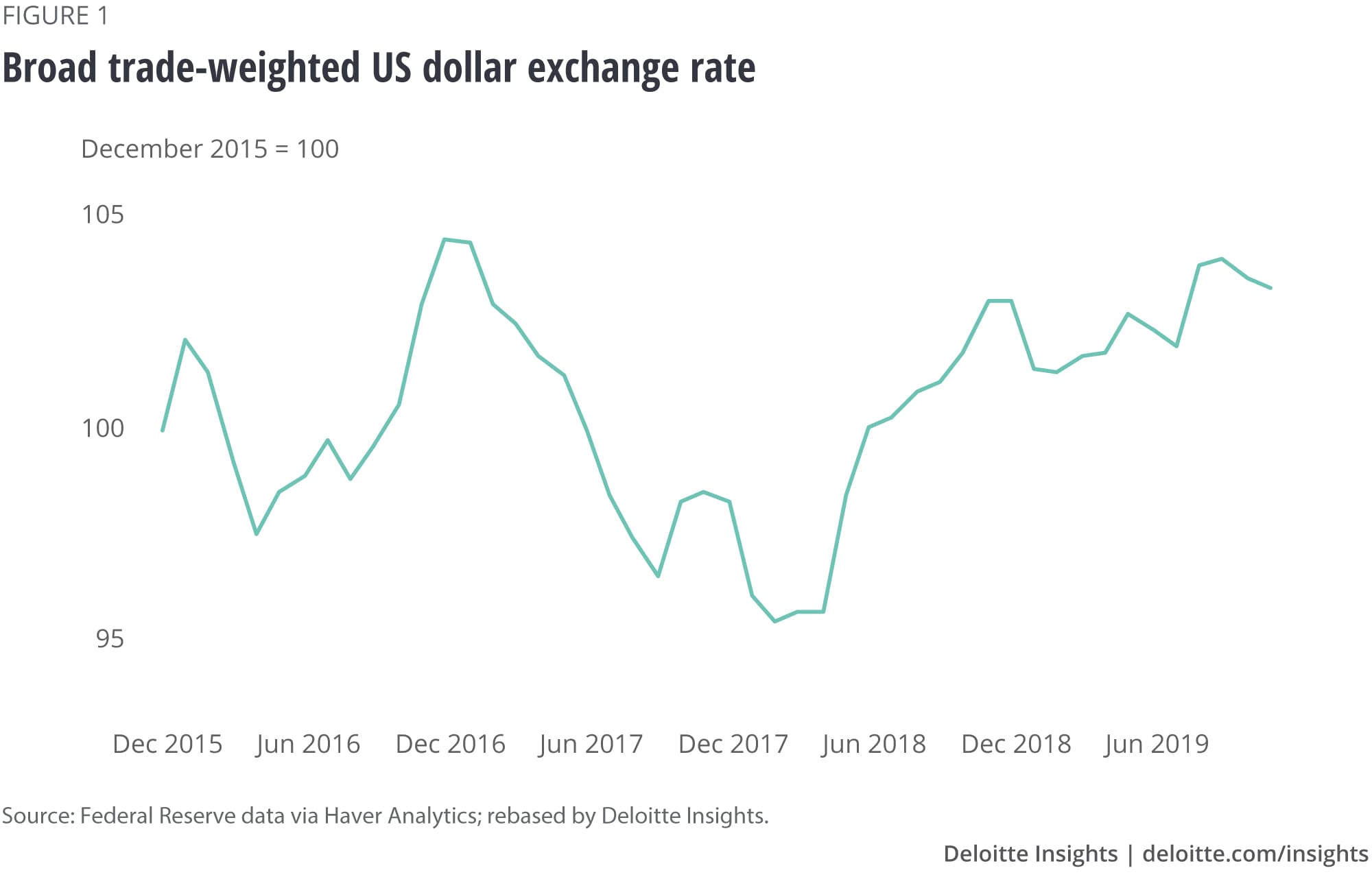

So what has the dollar been doing? Figure 1 shows the broad trade-weighted exchange rate of the United States over the past four years.2

There are, of course, dozens of US dollar exchange rates, as many as there are separate currencies. Figure 1 shows an average of these exchange rates using weights based on US international trade. The euro area has the largest weight (about 19 percent in 2019) because it is the largest trading partner of the United States. Then come China (16 percent), Canada (14 percent), and Mexico (13 percent). These weights have changed over time; in the 1970s, the Canadian dollar had a weight of about 25 percent.

As to what the trade-weighted dollar has been doing, the answer is, not much. In the past four years, it has been at a low of 108 and a high of 117. Exporters would certainly prefer the lower number, as the appreciation represents a significant rise of about 10 percent in the dollar’s value since early 2018. But such movements have been common since the advent of floating exchange rates in 1971–73. By now, global businesses have learned to use markets in foreign exchange futures and options to hedge exposure. It does make the job of corporate treasurer a bit more complex, but tools exist to reduce the risk that foreign exchange markets present to most corporations.

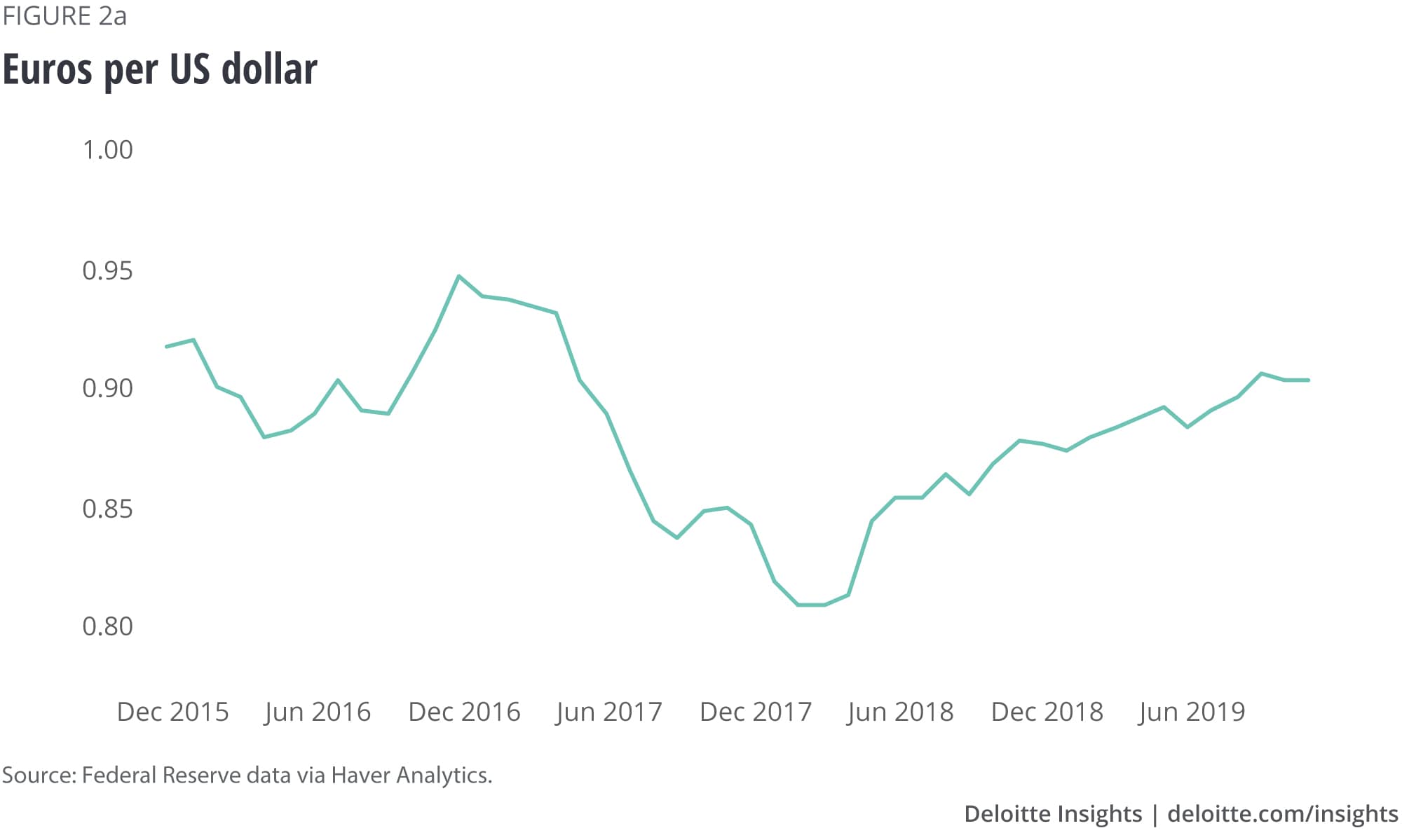

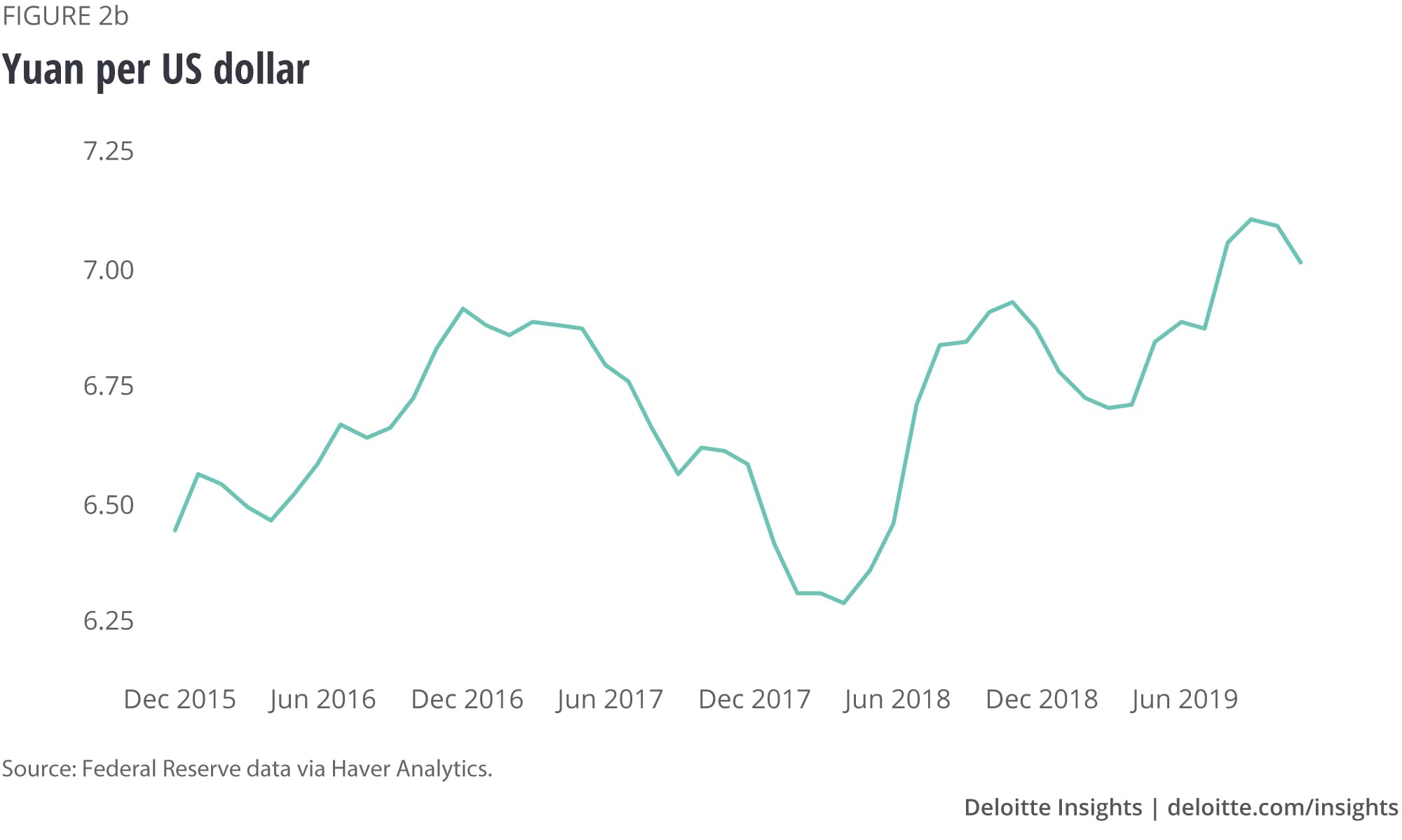

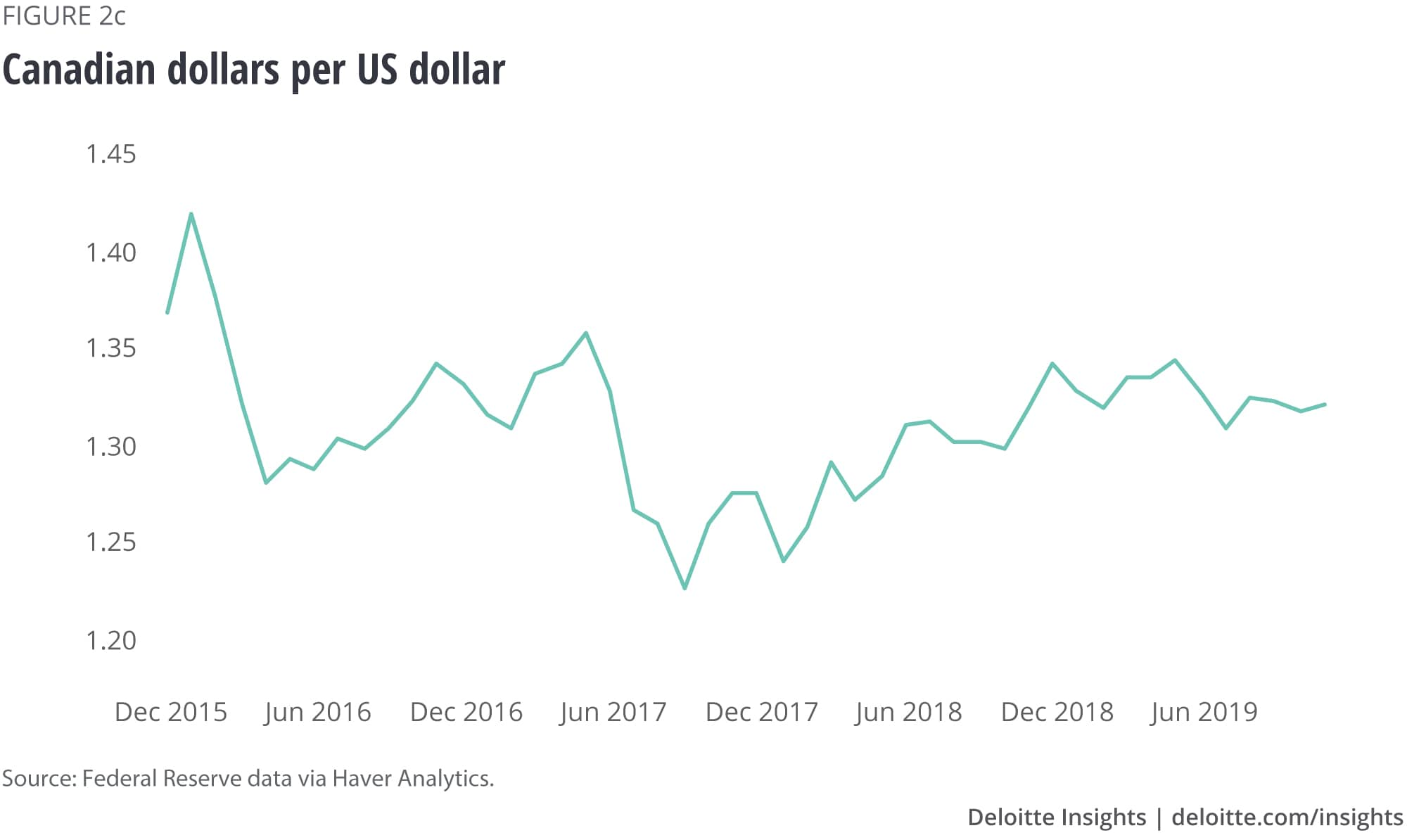

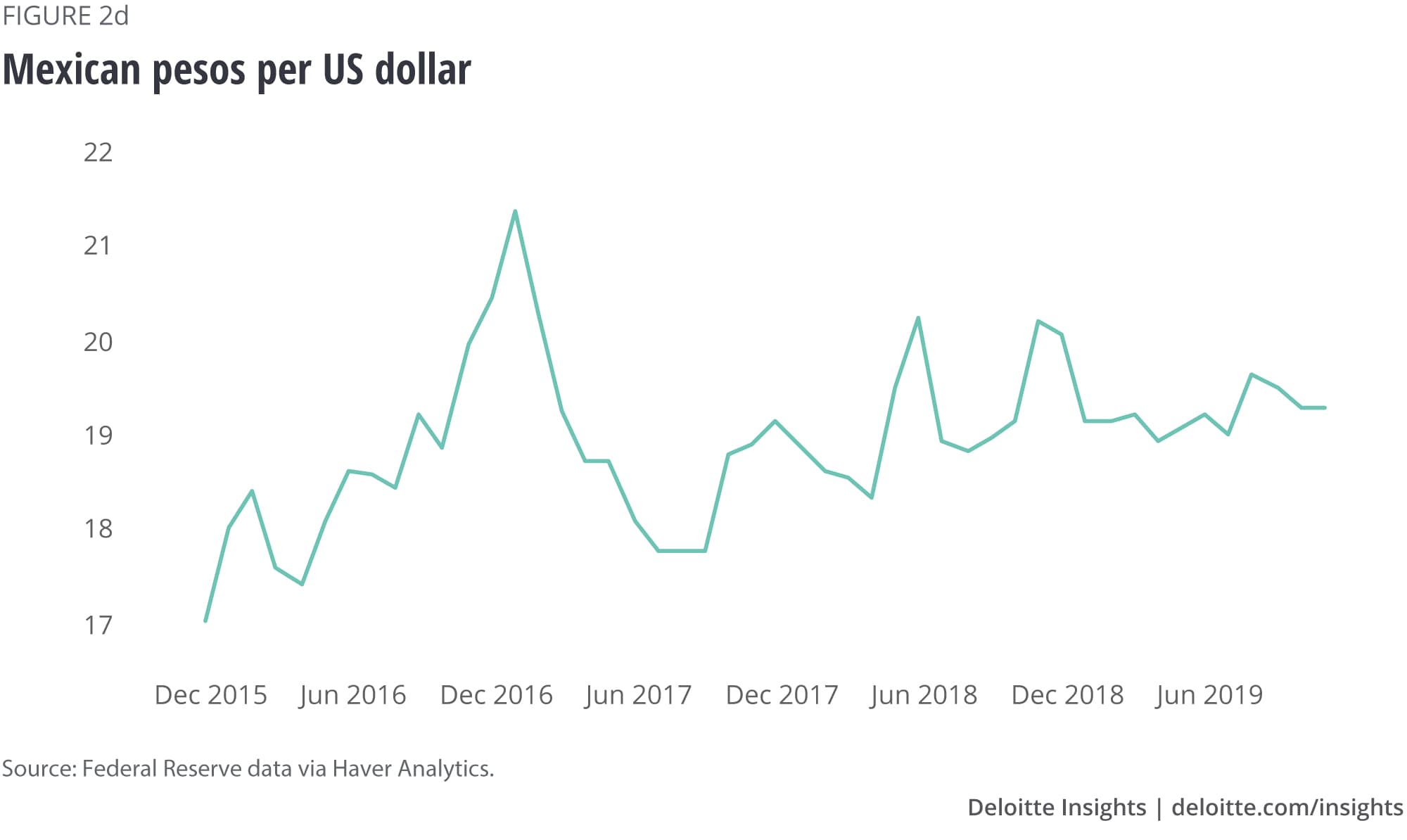

The trade-weighted figure masks some important bilateral changes. Figure 2 shows each of the four exchange rates that together comprise two-thirds of the trade-weighted dollar. In the past year, the exchange rates of the North American neighbors have been stable. In contrast, the dollar has appreciated about 10 percent since early 2018 against both the yuan and the euro.

These movements are typical for floating exchange rates, and don’t indicate that either the People’s Bank of China or the European Central Bank are taking any extraordinary policy measures. They probably reflect slowing growth in Europe and China: Slowing growth often means lower interest rates and lower profits. When that happens, global investors switch to faster growth countries (such as the United States last year), bidding up the price of their currencies.

We usually think of exchange rates as being closely related to trade flows. But only a small fraction of currency trades support exporters and importers. Most currency trades support flows of financial capital around the world. A German who has no intention of traveling to New York and riding the subway nevertheless needs to buy dollars if she wants to diversify her portfolio with US stocks or bonds. And an American needs euros to buy European stocks or German bunds. The consensus among many economists is that demand for financial assets is what really drives exchange rates, not demand for goods and services.

The United States is in a unique position when it comes to dollar assets. The dollar is the key global currency by several measures. About 63 percent of global foreign exchange reserves—official central bank holdings of foreign currency—are in dollars. (And the United States itself has relatively few foreign currency reserves, reflecting the fact that the US Treasury and Federal Reserve are confident of their ability to sell dollars on global markets if necessary.) Only 12 percent of foreign exchange transactions do not involve the dollar. And almost half of all debt securities issued around the world are in dollars.3 As the world economy grows, the demand for dollar assets keeps growing too. That helps to underpin the strength of the US exchange rate.

Something else underpins the US dollar exchange rate as well—the fact that global investors consider the United States to be the safest place in the world to stash financial capital. Geopolitical or global financial uncertainty sends global investors to update their portfolios by increasing the share of dollars (especially Treasuries), and that pushes up the price of dollars—the exchange rate.

Those financial factors make the dollar’s stability over the past few years pretty remarkable. From Brexit to trade wars, global policymakers have been finding new ways to add risk to the global financial system. But the impact on the US dollar has been relatively modest. US exporters have a lot of reasons for worry in the current economic climate, but the dollar’s stability is not one of them.

The theory of exchange rates

Exchange rates are prices. And, as any economist will be happy to tell you, the function of a price is to “clear” a market—to ensure that supply and demand are equal. Exchange rates, however, have to serve to clear two different markets with very different characteristics.

- In the international market for goods and services, the supply and demand for foreign currency changes relatively slowly because production and orders are often placed far in advance and can’t be easily changed. When it’s time to find dollars to pay for that new airplane, or for a tankerful of oil, the supplier wants their money—even though the price was agreed on months or even years before.

- The international market for financial assets, by contrast, adjusts very quickly. If there is a sudden demand for US dollar assets in foreign countries, global banks have no problem finding and supplying those assets. That, in fact, is a key reason for the dollar’s dominance in global asset markets—dollar asset markets are much larger and more liquid than those of alternative currencies, such as the euro.

The exchange rate is determined by adding the (slow-adjusting) supply and demand of dollars to buy and sell goods and services to the (almost instantaneously adjusting) supply and demand for dollar assets. That creates unusual dynamics for financial markets. When investors decide they want more assets in a given currency, initially they simply drive up the price. But that makes the country’s goods and services more expensive than its trading partners, which increases the trade deficit—meaning the country has to pay for more of its imports with precisely the financial assets that investors are clamoring for. The problem is that it takes time for trade flows to adjust so that more assets are available on global markets. The result is that foreign exchange markets can be very volatile in the short run.4

This is a key reason why focusing on a country’s trade balance can be very misleading. A large trade balance means that the country is selling a lot of assets to global investors. And when those assets are in high demand—as has been the case for US dollar assets for many years—it’s a global vote of confidence in the country supplying those assets.

More from the Economics collection

-

Global Weekly Economic Update Article4 days ago

-

A view from London Article4 days ago

-

Five themes that will drive Asian growth in 2020 Article4 years ago

-

United States Economic Forecast Q3 2024 Article2 months ago

-

What to expect when you’re expecting … a recession Article5 years ago

-

Monetary policy in advanced economies Article5 years ago