Falling interest rates: Puzzles keeping economists awake at night Economics Spotlight, October 2019

4 minute read

30 October 2019

Long-term US interest rates are at an all-time low. While that may be troubling news by itself, there’s also the fact that investment is not picking up—and that similar trends are apparent globally. Such a long-term trend could mean a low-growth scenario worldwide.

We may be used to being dismal, but even economists find some phenomena particularly disturbing. What sign in the economy is most troublesome? It’s not whether the Federal Reserve will raise or lower interest rates by a small amount at the next meeting. It’s not even the reversal of the yield spread, even though such reversals do tend to precede recessions. But a recession, bad as it might be, is just an interruption in the long-term growth of the economy.

Interest rates, however, are a different story.

Learn more

Explore the Economics Spotlight collection

Subscribe to receive related content

Download the Deloitte Insights and Dow Jones app

US interest rates have been hitting new lows—and, yet, investment is slowing

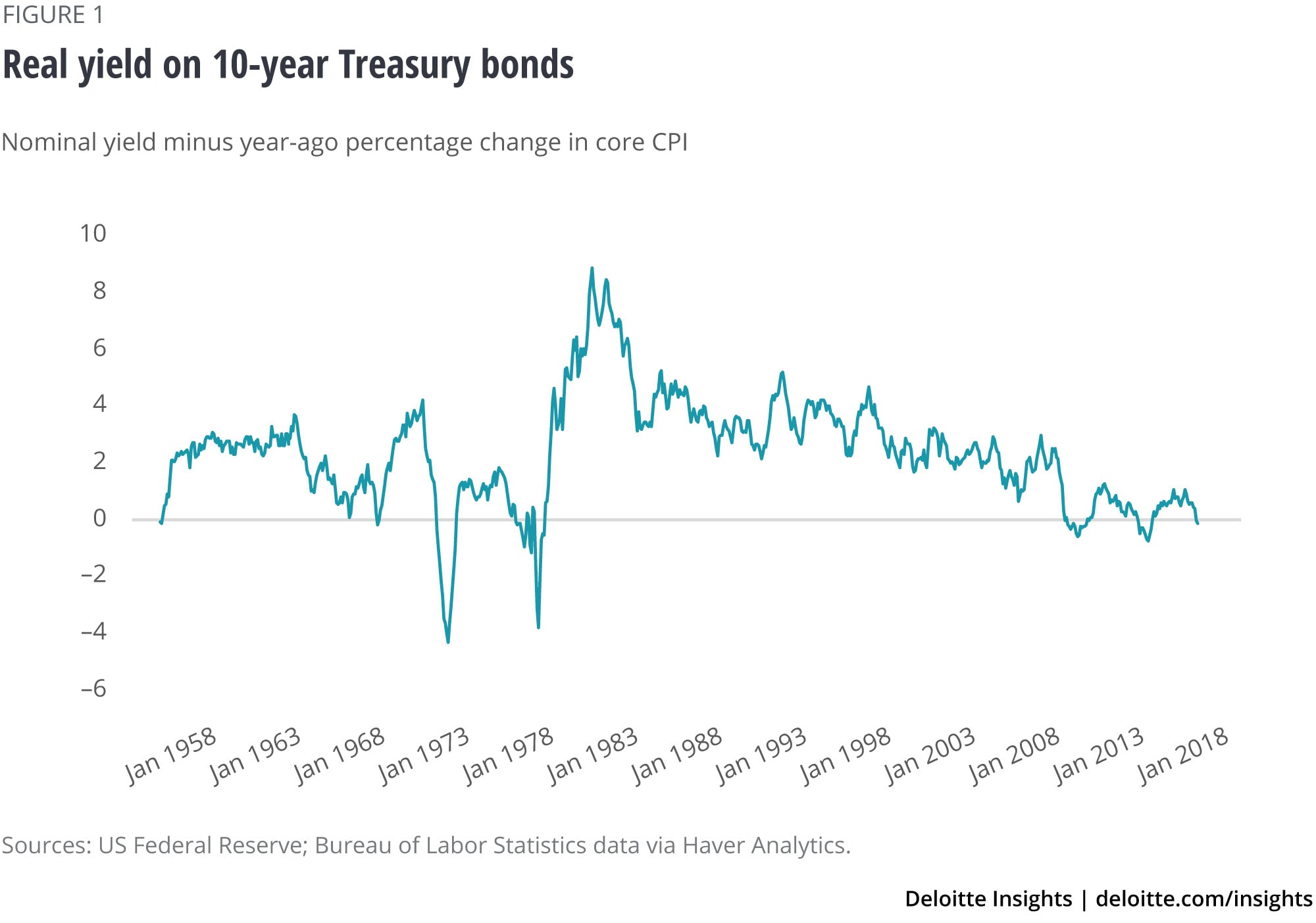

Long-term interest rates indicate a disturbing pattern. Figure 1 shows the real yield on 10-year Treasury bonds. In the first half of the 1960s, the real rate of interest held steady at around 2.5 percent. It fell in the latter part of that decade and remained low (except for a spike up in the early 1970s reflecting tight monetary policy). Both oil shocks coincided with temporary declines in the real interest rate as inflation picked up unexpectedly. Then, in the early 1980s, the Volcker monetary tightening took real interest rates up to very high levels for a time. Despite a drop in the latter half of the 1980s, they remained at a still high 4.0 percent.1

But then the real interest rate kept falling: first, to around 3.6 percent in the 1990s, then to around 1.8 percent in the aughts, and then averaged below 1 percent as the Fed created new methods of monetary accommodation after the global financial crisis in the 2010s. But, even as the US economy approached full employment, and even after the Fed tried to tighten financial conditions, the real rate remained low. The real rate between 2011 and today has averaged just 0.4 percent. In August and September 2019, it turned negative—something that, in the past, only occurred when inflation shocks caught financial markets by surprise (for example, during the 1974 and 1980 oil price shocks).

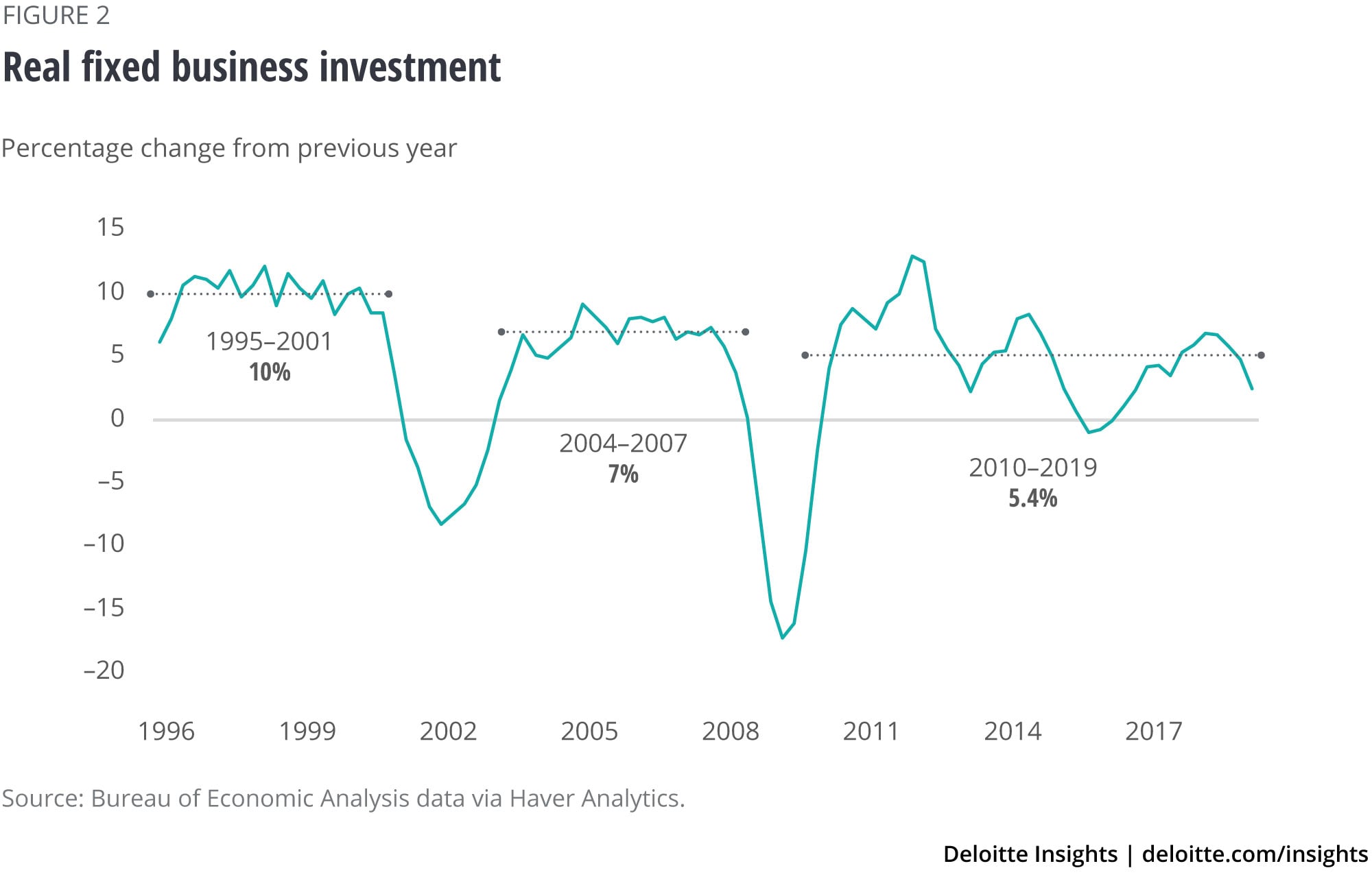

Most economists would expect such low interest rates to encourage investment. But that didn’t happen. Figure 2 shows that investment growth has ratcheted down with each recovery. The current recovery has seen investment growing at just over half the rate of the 1995–2001 period, despite substantially lower interest rates.

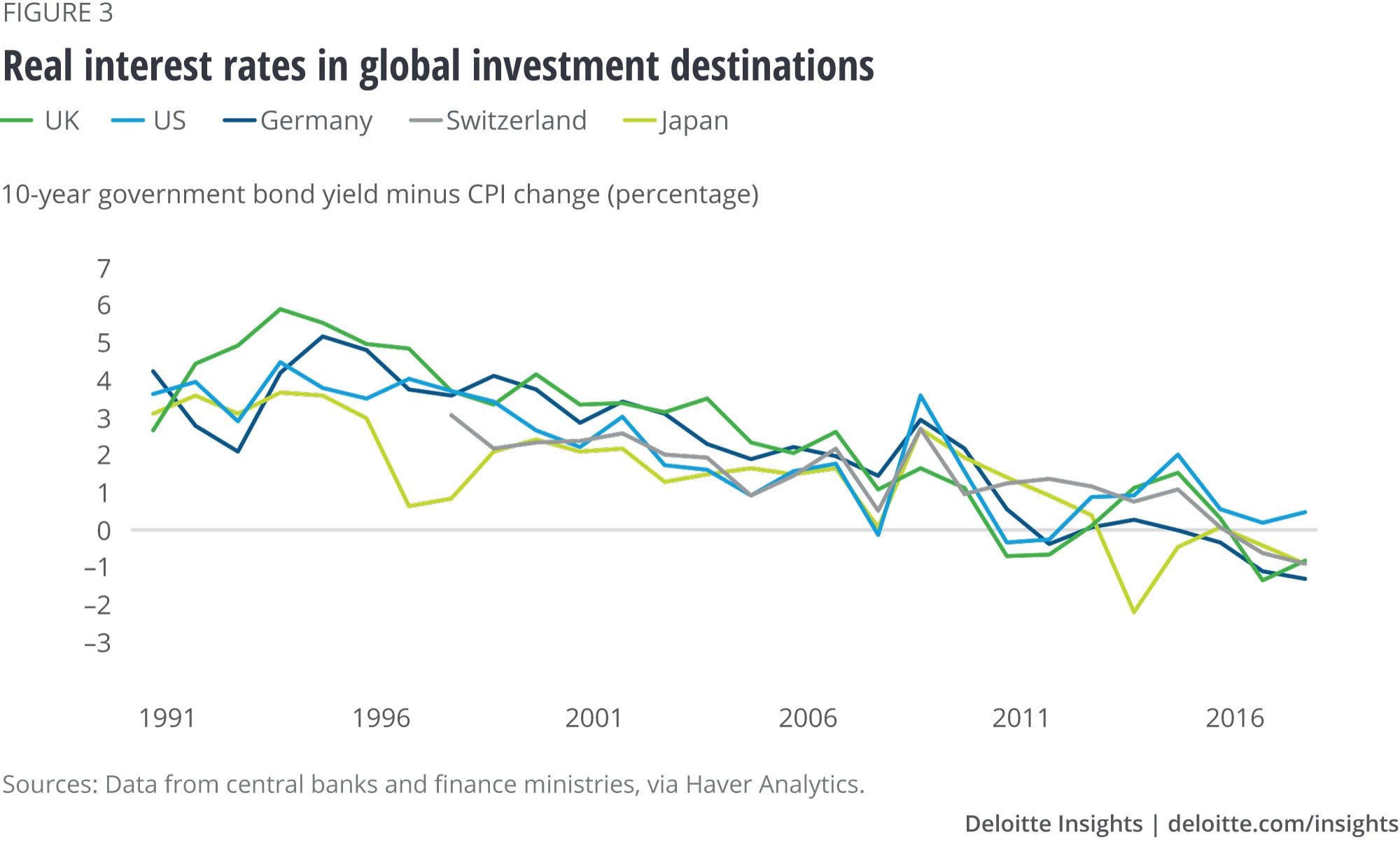

Low interest rates are a global phenomenon

This phenomenon, however, is not limited only to the United States—interest rates in other major global investment destinations have also fallen over the past 20 years (see figure 3). In fact, interest rates in the United States are relatively high. Most of the rest of the developed world has experienced negative real interest rates for the past year or two—in Japan’s case, even longer. These negative real rates are quite different from the negative real rates recorded in the 1970s. Then, the problem was that financial markets were taken by surprise by high inflation. Negative real interest rates were not a planned outcome. There is some question about whether investors really understood that they were taking losses at what appeared to be high nominal interest rates. Eventually, investors learned to price future inflation into asset prices, and real interest rates returned to “reasonable” levels.

Today, inflation is low. There are no resource price shocks, and investors are not being fooled by high nominal rates. In European countries where nominal rates have gone negative, lenders know very well that they are paying borrowers to borrow. It may be crazy, but they are doing so anyway.

Why are interest rates falling?

The decline in real interest rates over a long period of time is a puzzle for economists. Likely explanations include:2

- Trend productivity growth has slowed, making capital investment less productive. In equilibrium, the interest rate should be related to the return on capital, so lower capital returns would lead to lower long-term interest rates.

- There is a global savings surplus, as certain economies (China and Germany are the most cited) have oriented their economies toward exports and high savings levels. Global investment demand is not large enough to absorb the global savings surplus, so the return on savings (the interest rate) has fallen.

- The aging population saves more and has less demand for capital-intensive consumer products. The combination of low savings and less need for capital has pushed down interest rates.

- Low expected inflation means that the term “premium” (essentially, the expected change in short-term rates) is lower than it was in the past. We often compare current interest rates to averages over the past—but if inflation expectations are very different today, those past averages may be misleading.

While economists love puzzles, this one is disturbing. It suggests that monetary policy may be in the process of becoming less effective, and that maintaining full employment could become more challenging in the future. The potential “Japanification” of the global economy would see the entire world stuck in a low-growth equilibrium with few policy options to alleviate the experience of slow income growth—and worse, few tools ready to help fight economic downturns.

More from the Economics collection

-

Monetary policy in advanced economies Article5 years ago

-

Balancing payments Article7 years ago

-

In whose interest? Examining the impact of an interest rate hike Article8 years ago

-

Retirees of the future Article5 years ago

-

Personal savings: A look at how Americans are saving Article5 years ago

-

Global Weekly Economic Update Article3 days ago