United States Economic Forecast 4th Quarter 2020

20 minute read

16 December 2020

Vaccine development is undeniably good news for consumers and businesses. But the damage to the economy, from shutdowns and withheld aid, has already been done. The coming months will show the extent—and suggest the direction of the recovery.

Introduction: What’s the damage?

One of the biggest unknowns about the economy is just how bad the damage is. When people first reacted to the pandemic in February and March by canceling travel plans and restaurant reservations, most expected the disruption to be short-lived. Almost a year has passed, with people having to reset expectations and plans every month or two. And notwithstanding the development of several apparently effective and safe vaccines, widespread distribution of these vaccines is unlikely until (at the earliest) summer or fall 2021. Full recovery will therefore start from a very different point than anybody expected last spring.

Learn more

Learn how to combat COVID-19 with resilience

Explore the Economics collection

Learn about Deloitte's services

Go straight to smart. Get the Deloitte Insights app

In March, many businesses expected to shut down or change operations for a few weeks or, at worst, months. Much planning, and government policy, was designed to bridge this relatively short period. Managing to operate during the pandemic for over a year is a different challenge—and a daunting one. A substantial number of businesses—especially small businesses—have already failed or will not survive, despite the Federal Reserve’s best efforts to keep credit cheap and easily available. Replacing and/or resurrecting those businesses once the pandemic is over will require more resources and investment than if they had remained operational.

Meanwhile, many workers who assumed disruption would be short-term found themselves tied down at home for what turned out to be most of an entire school year, managing their jobs and children’s education at the same time. The pandemic has been especially brutal for women because of this: By September, the labor force was down some 5 million people from the peak in February, with women making up a disproportionate number of those who left the labor force.1 The total number of employed workers was down 10 million, or over 7%, from the February peak. Worse, the number of people unemployed for a long period of time is growing quickly; long-term unemployment is associated with a number of bad outcomes, including lower productivity (and lower wages) for these workers when they do finally return to work.2

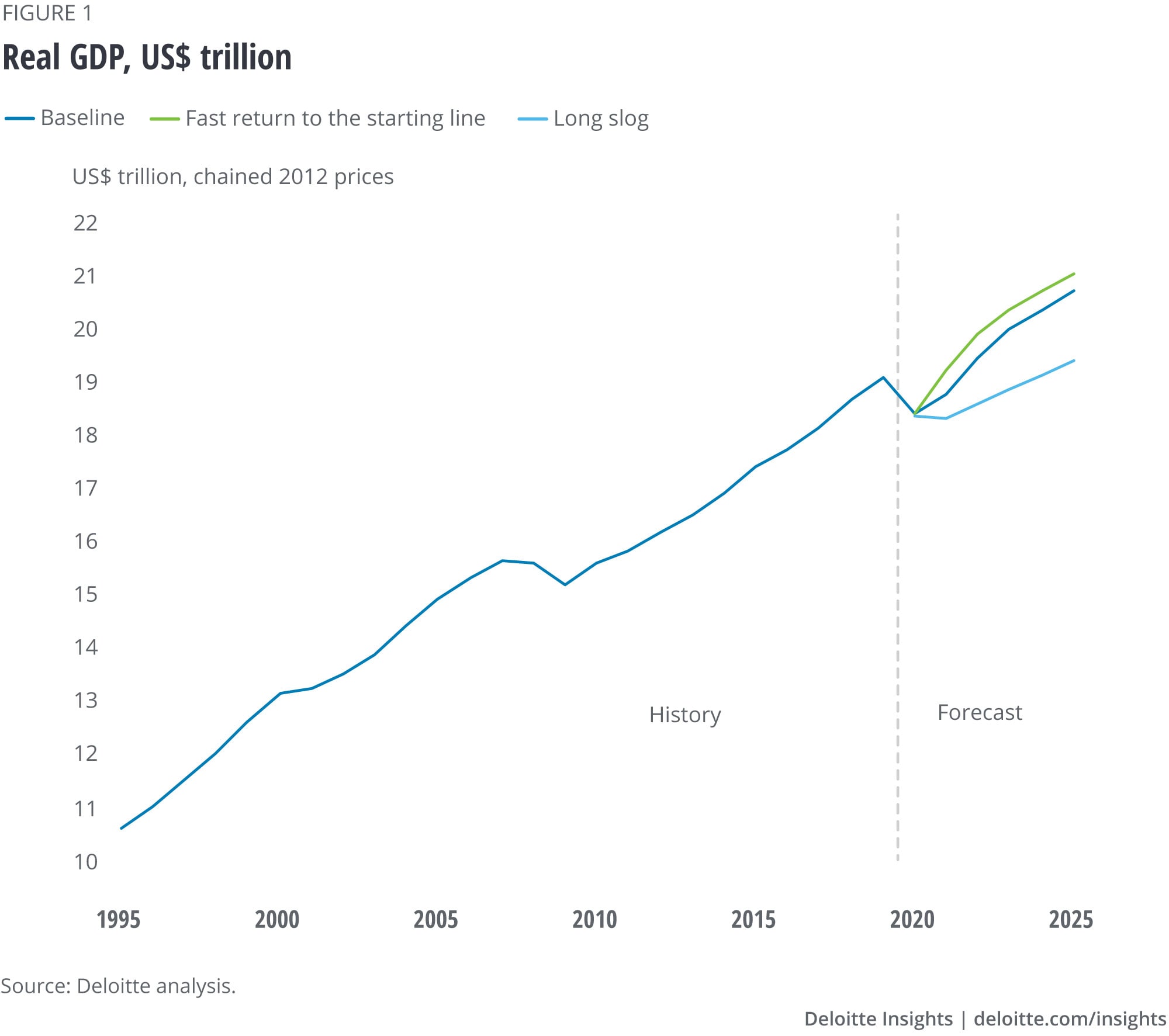

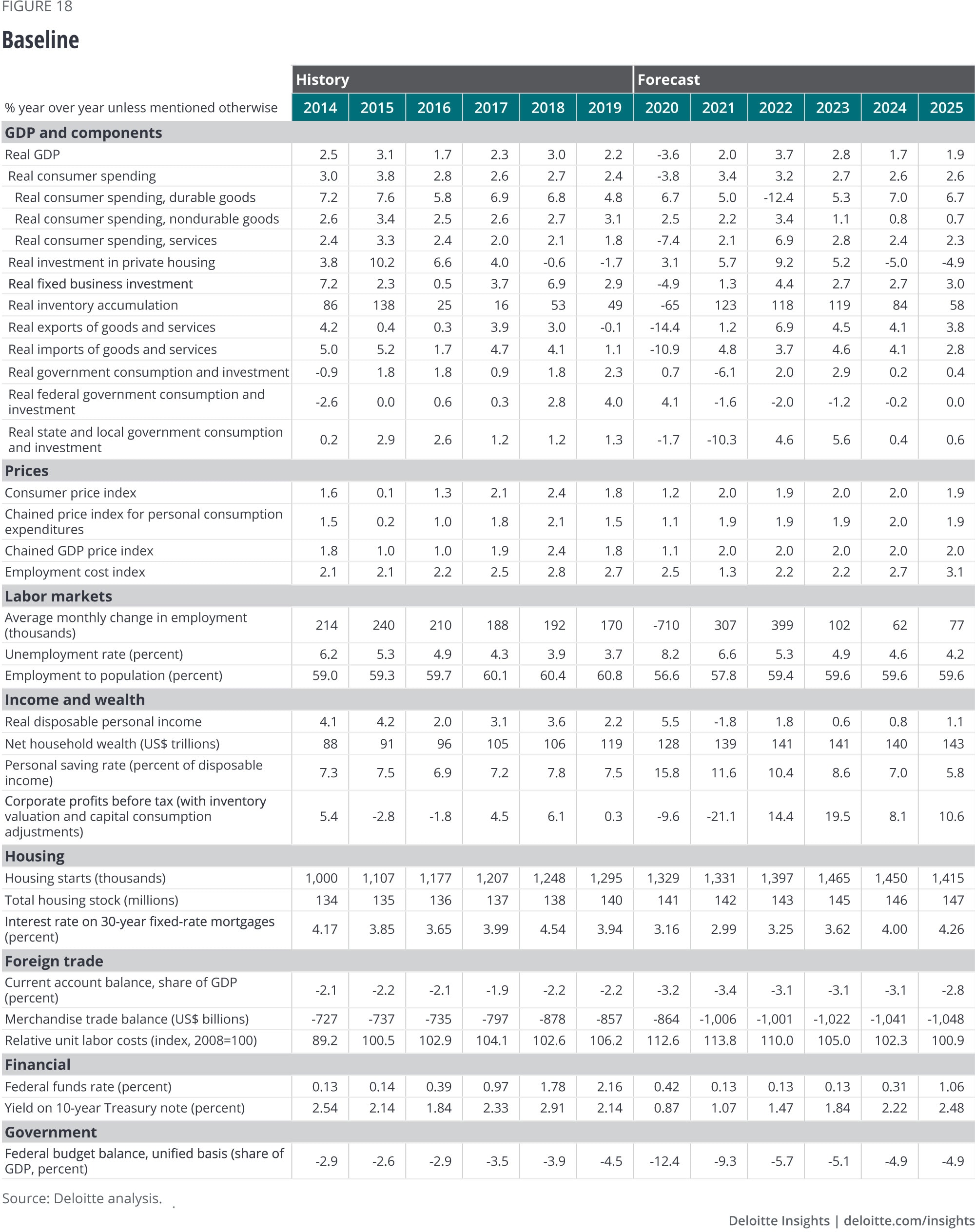

Just how bad will the damage prove to be? We won’t know until recovery really gets underway. Our baseline scenario assumes that the damage is sufficiently critical that growth—particularly employment growth—will be restrained after an initial period of recovery, and that the economy will remain 2% below the prepandemic trend during the five-year forecast horizon.

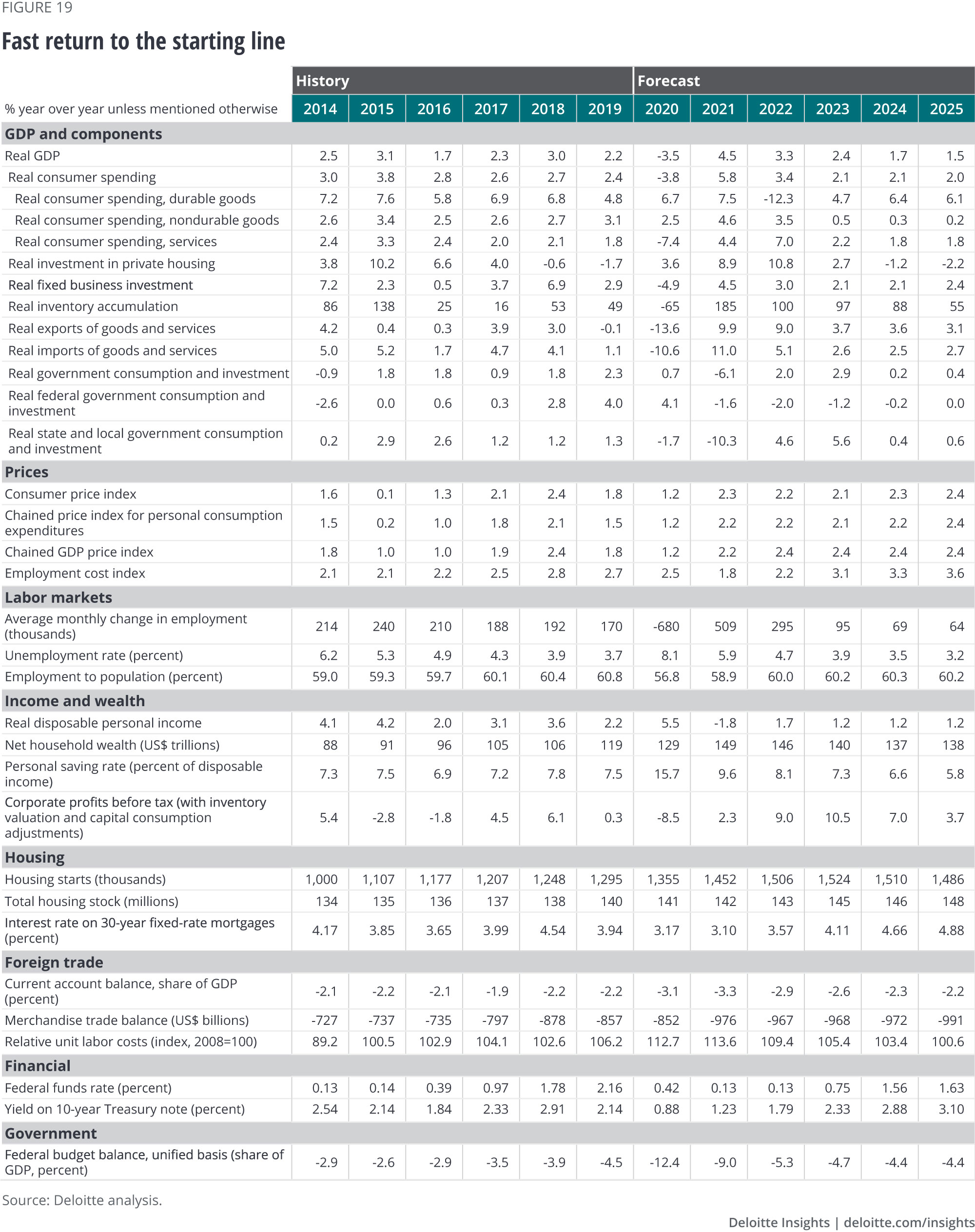

But we’ve included an optimistic scenario in this forecast, one that assumes that pent-up demand quickly boosts sectors such as travel, food and accommodations, and recreation services once the threat of the pandemic goes away. And since these sectors tend to employ lower-paid and therefore lower-skilled workers, rehiring can happen more quickly than in sectors such as durable goods manufacturing that are typically hit hard during recessions.

Another part of this story is the Fed’s work in keeping the financial system operating during the pandemic.3 Banks have remained well capitalized, and many companies have been able to borrow at relatively easy terms. The economy, then, has avoided the shutdown of large companies for financial reasons, and if that remains the case, economic activity can pick up quickly. Consider, for example, the fact that large airlines remain solvent and ready to expand service when necessary—if that were not the case, recreating airline services once the pandemic is over would be considerably more expensive and time-consuming.

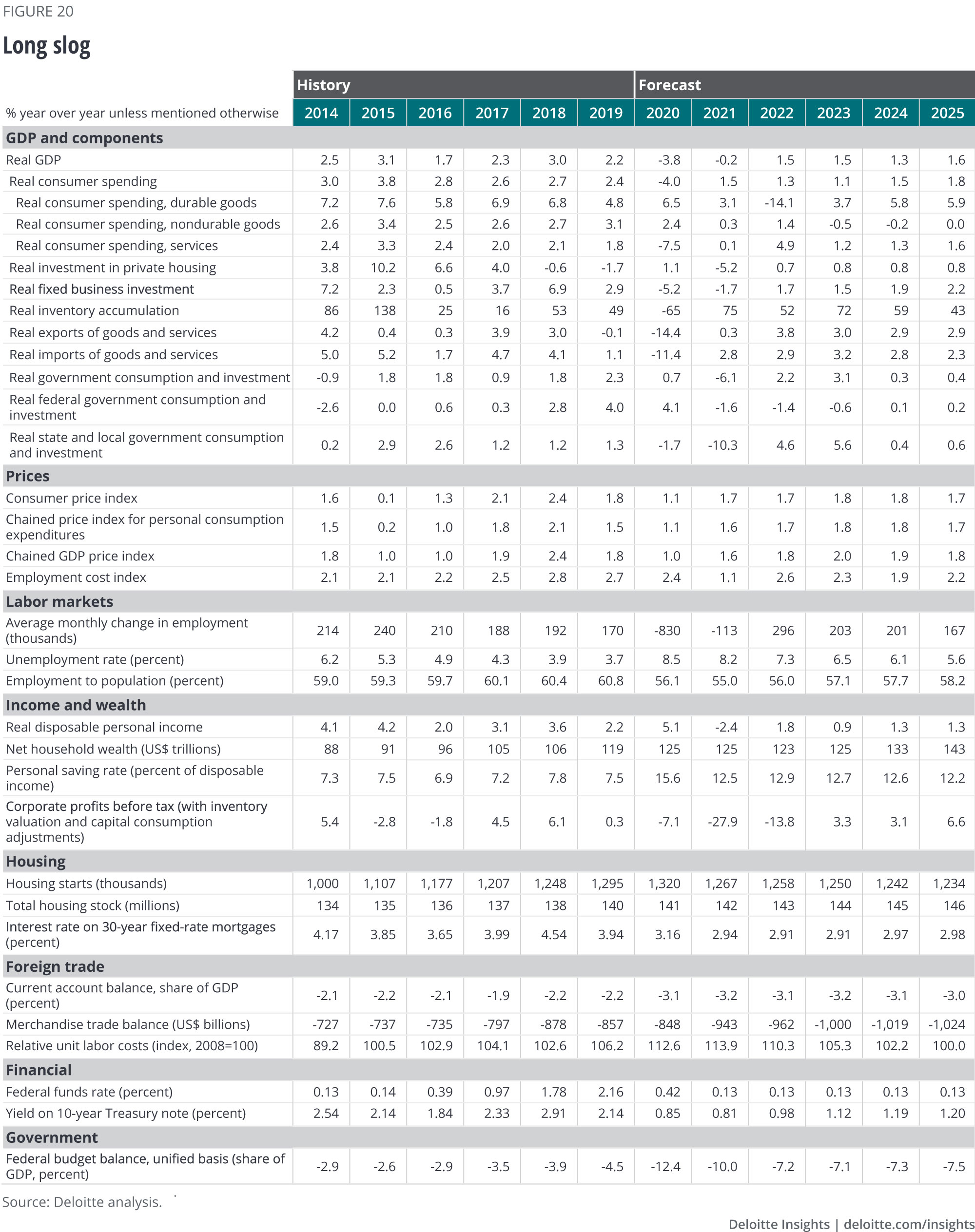

And good news about vaccines has enabled us to lower the probability of our long slog scenario from 25% to just 10%. Whether or not the specific vaccines in the upbeat November headlines prove to be winners, the likelihood of an effective vaccine being deployed seems to have increased sharply. Granted, significant hurdles remain, including many Americans’ reluctance to be vaccinated,4 keeping the possibility of the long slog scenario at a significant level despite the positive vaccine news.

To be clear: The economy remains in troubled territory, fresh optimism notwithstanding. Even after the third quarter’s rapid growth, GDP remains 3.5% below its peak in 2020 Q4. That’s not too different from the maximum decline from the peak in the 2007–09 recession and would take about a year and a half to reverse at the recent years’ average GDP growth rate. And the economy is clearly slowing as of late November. Our baseline continues to show very slow growth until mid-2021, with the distinct possibility of a negative first quarter in 2021. The relatively small federal relief bill that is the most probable policy intervention will likely provide too little help, and in the baseline the damage done to business and labor markets takes years to fix. Business leaders may hope for the best, but it’s best to prepare for a slow recovery.

Scenarios

Baseline (65%): The lack of a substantial relief package leads US GDP to stall, starting at the end of 2020. The failure to extend unemployment insurance (and raise benefit levels) weighs on consumer spending. And the need for state and local governments to cut spending creates an additional drag on GDP. The fall spike in COVID-19 cases requires additional closures and prevents many people from wanting to resume normal activities. Schools turning to virtual learning prevent potential workers (especially women) from returning to the labor force, so employment growth slows. The new vaccines being developed are deployed narrowly (to health care workers and first responders) at first, with little economic impact in the first half of 2021. State governments succeed in broadly deploying vaccines by mid-2021, and economic activity then starts to pick up. Potential GDP remains about 2% below the prepandemic trend in 2025.

Fast return to the starting line (25%): A significant relief bill keeps demand growing in the first half of 2021, and then pent-up demand creates a large burst of spending starting in mid-2021 as vaccines are widely deployed. Consumers are sitting on considerable savings and are ready to spend. And unlike in previous recessions, the Fed has prevented significant financial damage to the economy. Banks remain well capitalized and able to lend, and businesses are solvent and willing to spend money to make money once customers return. In addition, most of the job losses have occurred in sectors that hire low-skilled workers, and those sectors (food and accommodation, travel, and recreational services) can scale up quickly when demand recovers. GDP accelerates swiftly once vaccine deployment becomes widespread.

Long slog (10%): COVID-19 cases continue to climb through the winter, and states are forced to attempt to again limit economic activity. Schools meet virtually, and some parents leave the labor force to manage their children’s schooling. The unavailability of either treatment or an effective vaccine means that the cycle of restart attempts and subsequent reclosing continues. This limits the possibility of recovery and erodes trust in institutions; even as treatment improves and businesses again reopen, consumers prefer to stay at home in safety rather than take what they have come to believe are unwarranted risks. Any additional economic recovery is hesitant, and GDP growth remains relatively slow. As far out as 2025, unemployment remains high, with the level of GDP about 8% below the level it would have reached had the pandemic not occurred.

Sectors

Consumer spending

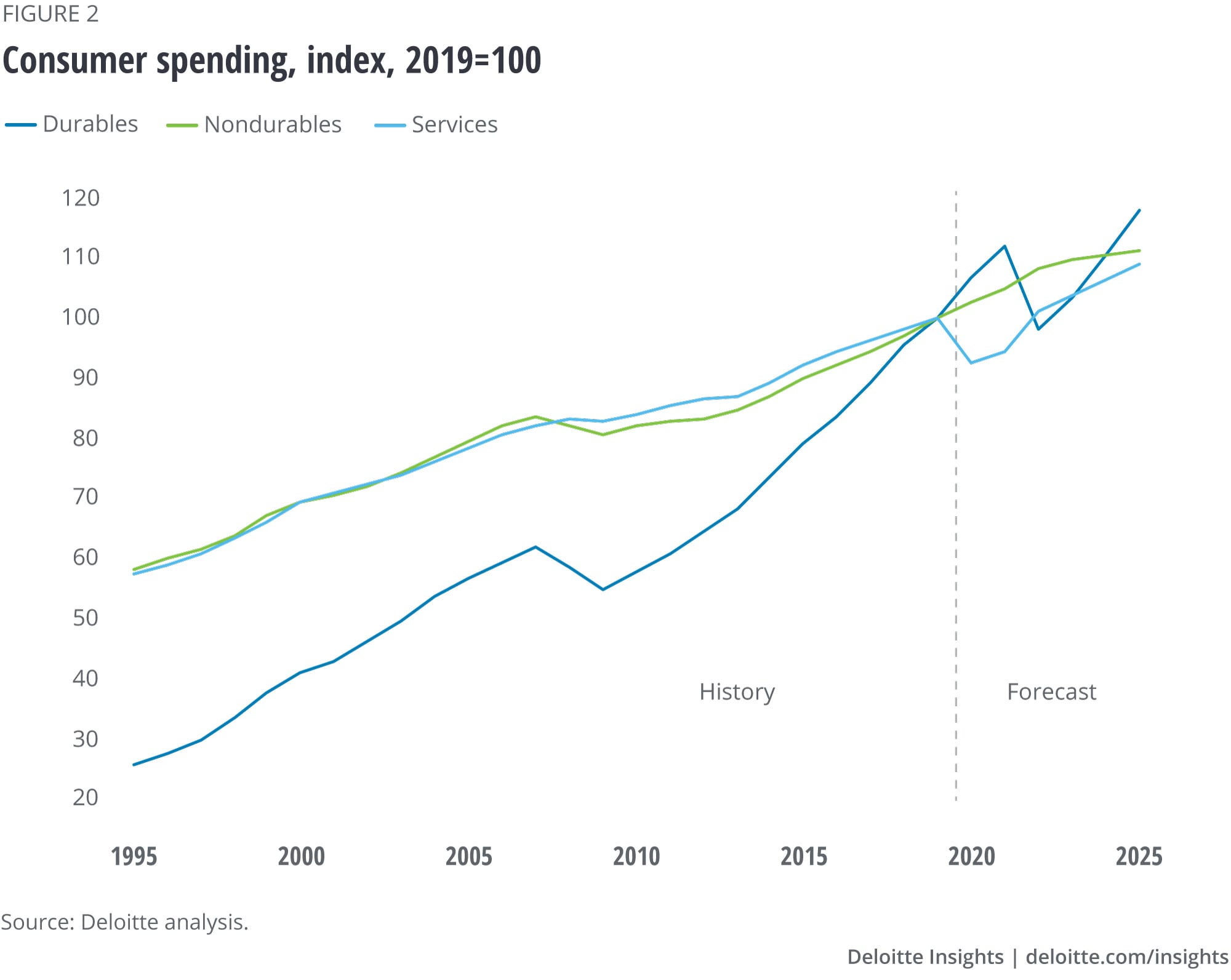

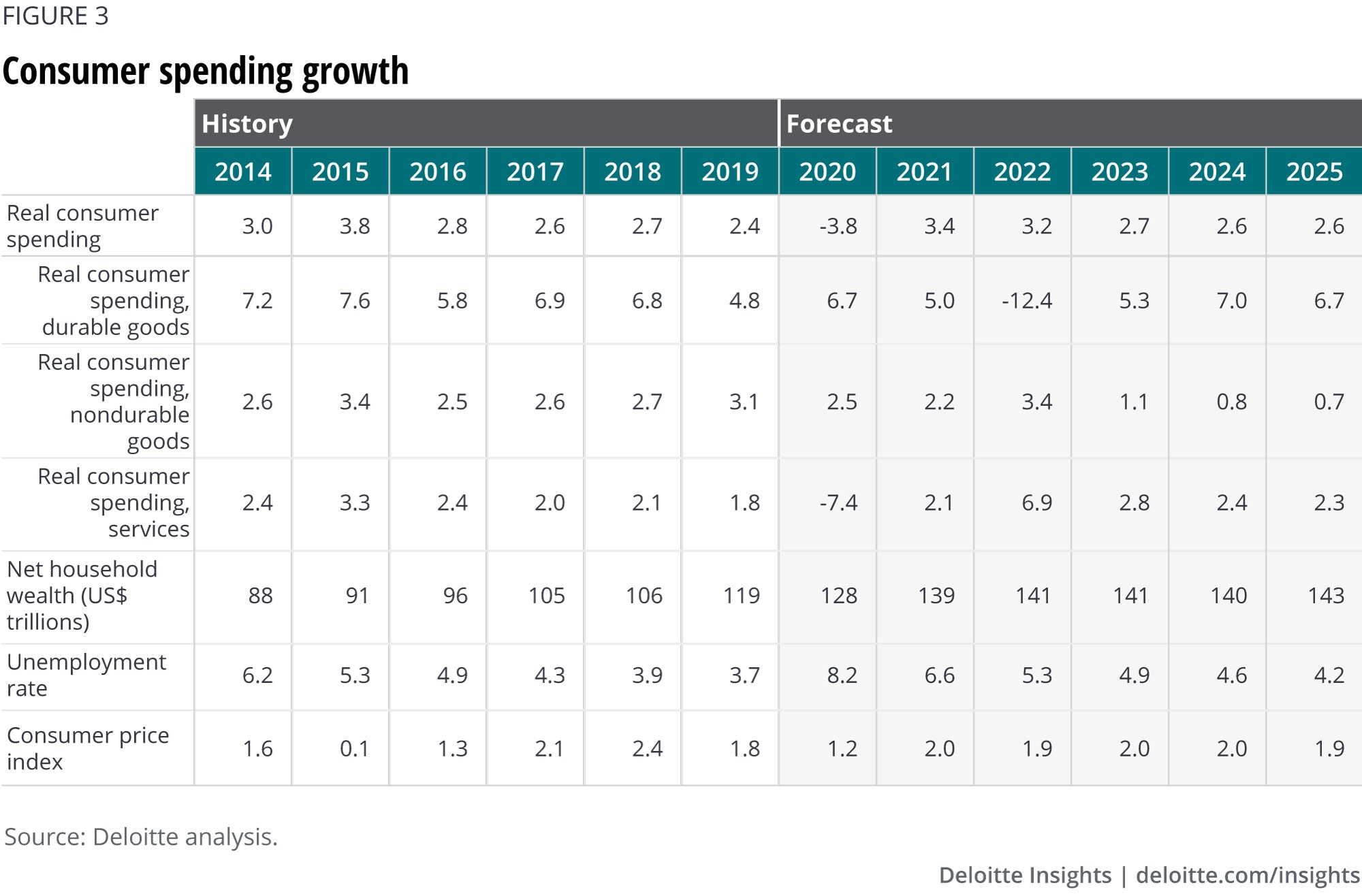

Consumer spending has been surprisingly strong over the past few months. Despite the withdrawal of the US$600 weekly supplement to unemployment insurance at the end of July, and despite rising cases of COVID-19 across the country, people continue to be willing to spend. This is partially because of the massive savings that occurred early in the pandemic, when even the unemployed increased savings.5 And job creation, although slowing, is still large enough to add to incomes—and to support consumer spending.

The pandemic dramatically changed patterns of spending, however. In the third quarter, goods accounted for 34% of consumer spending (up from about 31% before the pandemic), with services falling correspondingly to 66% of spending. Until medical interventions render COVID-19 considerations moot, spending is likely to continue to shift away from activities that consumers perceive as risky—entertainment, food service, accommodation—and toward consumption that can take place in a socially distanced way.

The promise of a vaccine raises the question of how consumers will behave once the coronavirus is no longer a threat. One possibility (consistent with our baseline) is that consumers will remain wary for some time. This suggests that households will maintain a higher level of savings, and that consumer services spending will recover slowly. Another possibility, shown in our fast return scenario, sees consumers rapidly returning to their previous spending patterns.

Spending on durable goods has been particularly strong, rising 13% from January through March. This poses another problem: Even before a vaccine is widely deployed, consumers may exhaust their demand for durable goods that substitute for services spending. After spending the mostly unused restaurant budget of six months on a home gym, what does a household do with the next six months’ restaurant budget? Some durable goods suppliers, such as automobile manufacturers, are used to boom-bust cycles in consumer demand. Others may experience this for the first time.

In the longer term, we expect the pandemic to exacerbate existing consumer problems. COVID-19 has thrown the problem of inequality into sharp relief, straining the budgets and living situations of millions of lower-income households. These are the very people who are less likely to have health insurance—especially after layoffs—and more likely to have health conditions that complicate recovery from infection. And retirement remains a significant issue: Even before the crisis, fewer than four in 10 nonretired adults thought their retirement was on track, with one-quarter of nonretired adults saying they have no retirement savings.6 Low interest rates will worsen Americans’ preparation for retirement, while the stock market boom will have little impact on the balance sheets of most Americans.7

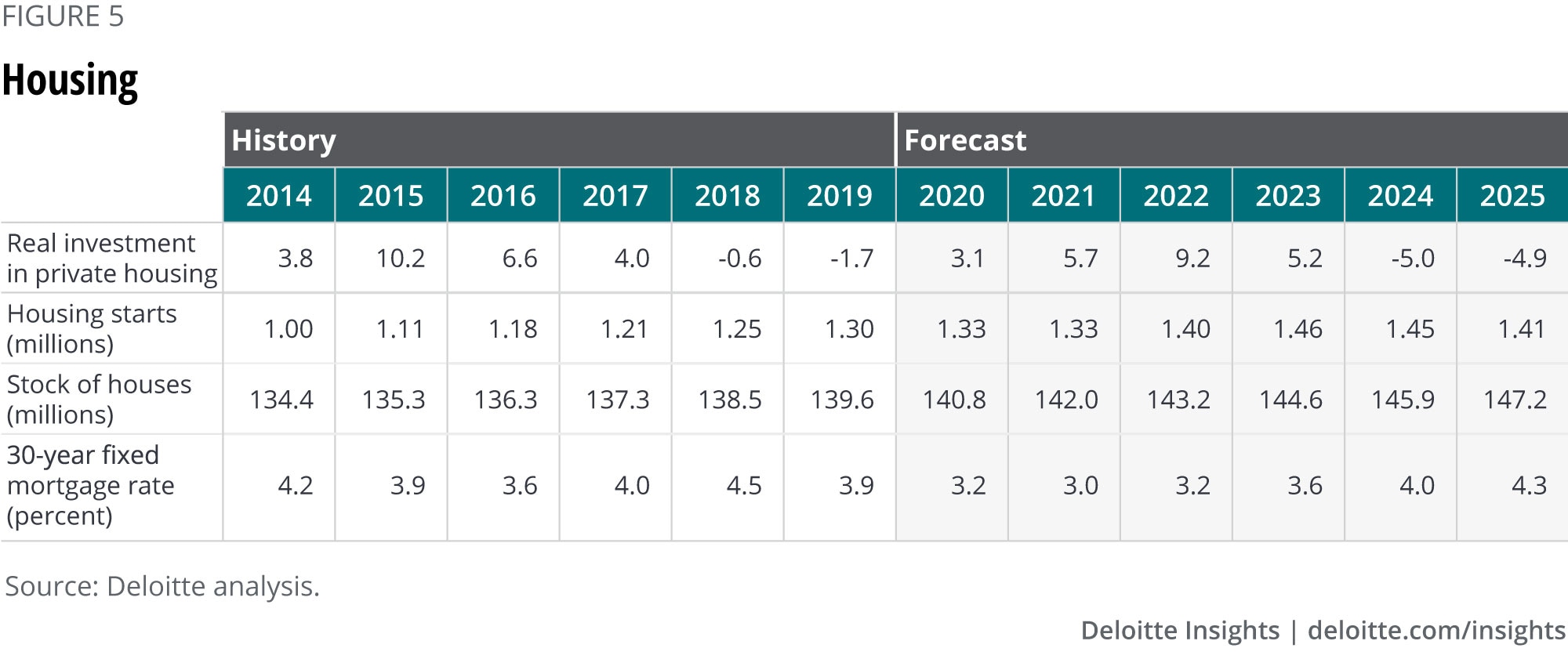

Housing

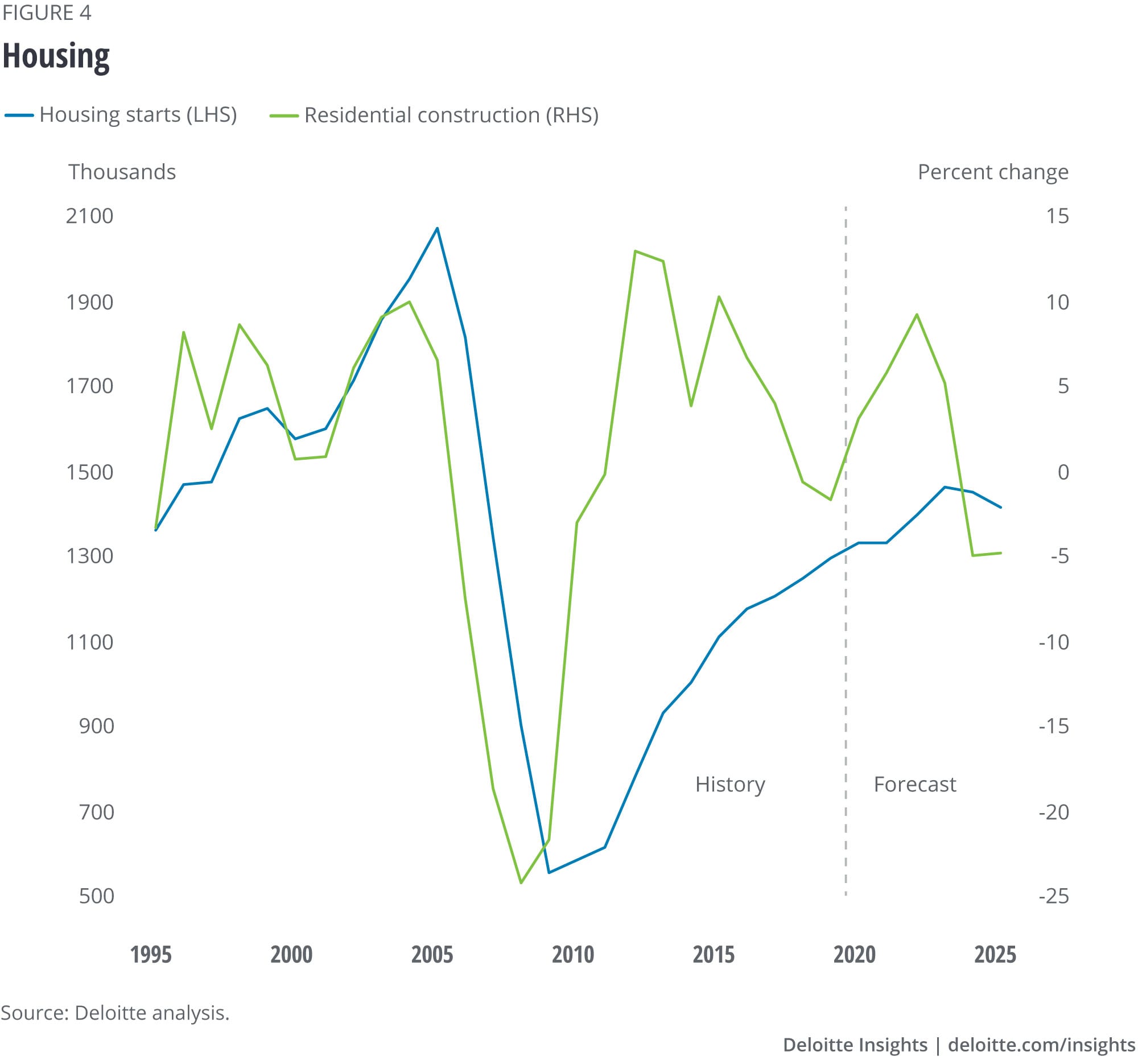

The housing sector has outperformed the broader economy in the wake of the pandemic. Apart from the fact that buyers and sellers have found ways to navigate the restrictions of the pandemic, a few factors have combined to boost housing demand.8 These include the continued strong economic positions of high-wage remote workers, historically low mortgage rates, and more millennials moving into prime home-buying age. This has lifted homebuilder confidence above pre–COVID-19 levels, and by October, housing starts had already made up almost all the ground lost between February and April. High-wage remote workers have been relatively unscathed during the pandemic, have benefited from rising home equity, and are likely to require more space as remote working persists. Moreover, the 30-year fixed-rate mortgage has been below 3% since July. This has been a major attraction for buyers despite the weak labor market.

Strong demand coupled with suppressed housing supply are likely to boost house prices in 2020 and 2021. Once the labor market recovery is clearly underway, we might see a further spurt in housing activity.

Even though a wave of millennials entering home-buying age might boost the housing sector in the short to medium term, long-run fundamentals ensure that housing does not become a key driver of economic growth in our forecast. Slowing population growth means that the demand for housing will grow relatively slowly after the initial jump in housing construction as the pandemic impact subsides in the baseline. Moreover, an aging demographic means that more than a quarter of the nation’s existing owner-occupied homes are likely to become available over the next 20 years as the current owners either pass away or vacate their homes.9

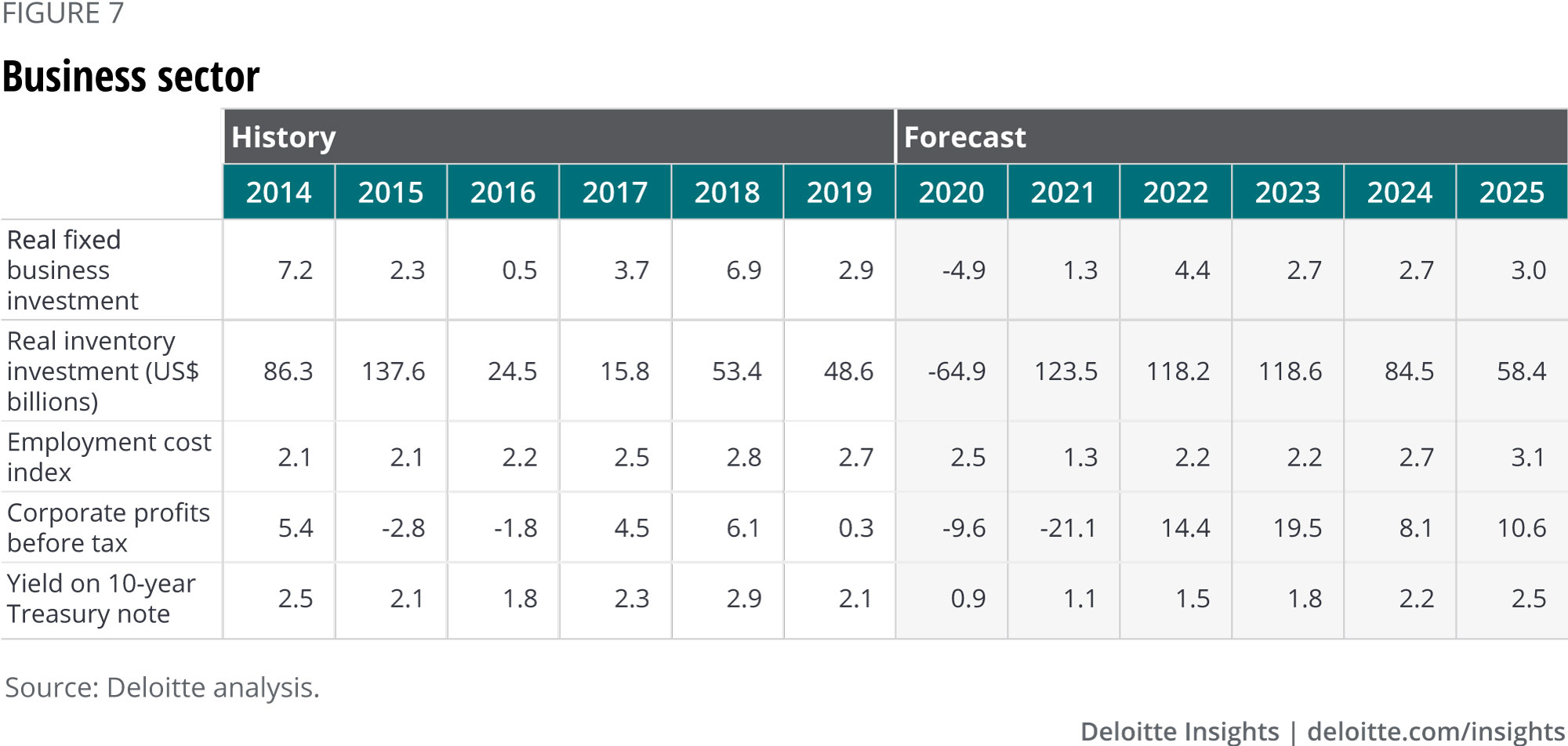

Business investment

Much of business investment was interrupted, like everything else, by the closing of the economy to slow the pandemic’s spread. Investing in certain specific areas that supported virtual operations registered an impressive gain—business purchases of information processing equipment, for instance, rose 5% even as GDP fell in the second quarter. But this was insufficient to keep overall investment from dropping. Structures investment has continued falling but was offset by continued growth in information processing equipment and a bounceback in other types of equipment investment.

Businesses now face uncertainty in several dimensions. There is uncertainty about the disease itself, raising difficult-to-answer questions for any business—questions about operations, customers, and costs. There are questions about the financial system and the ability to fund new investments. And there are questions about the recovery—how quickly the unemployed will be able to find new jobs once the crisis is passed, and whether the government response will help the recovery.

These considerations may cause business investment to remain muted for some time. The forecast assumes that business spending will remain relatively soft until the overall economy begins to steadily recover in mid-2021.

At that point, there may be reasons for businesses to begin increasing investment. Some of those reasons, unfortunately, may actually reduce productivity. First, many businesses will need to spend on safety equipment that will neither improve productivity nor add to profits. Second, government policy may encourage reshoring in “strategic” industries, especially medically related industries such as instruments and pharmaceuticals, arguing that it’s worth some inefficiency to obtain better national control over these areas in a future crisis. Third, businesses are likely to consider investing in ways to make their supply chains more robust, including reshoring, diversifying suppliers, and/or increasing inventories of critical products. All of these will likely help prevent extreme events from shutting down production but reduce efficiency and add to costs in normal operation.

The United States may, therefore, see relatively high levels of investment in this recovery. But it may not achieve the higher productivity we would normally expect that investment to generate.

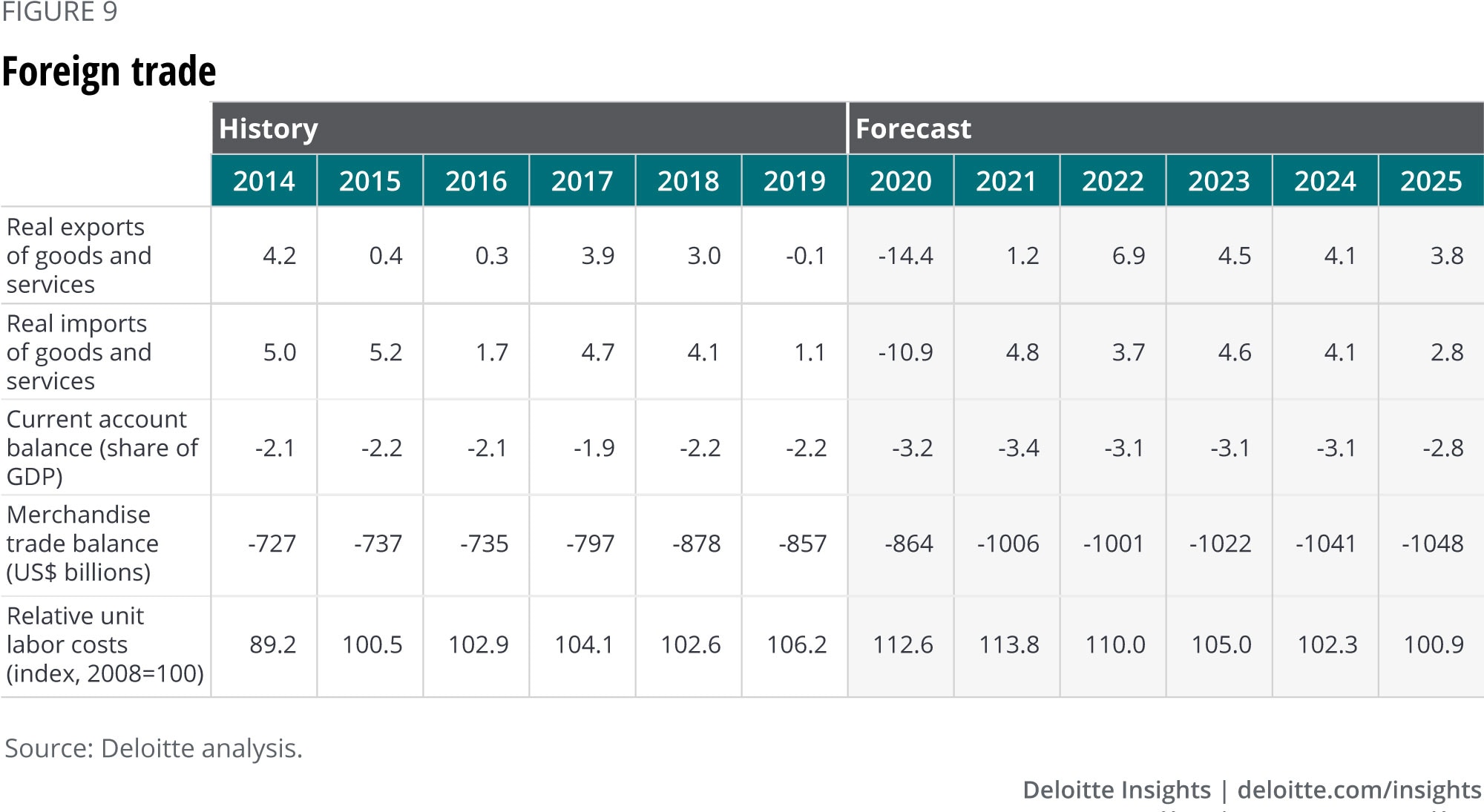

Foreign trade

Over the past few years, analysts have begun to face the possibility of deglobalization. Global exports grew from 13% of global GDP in 1970 to 34% in 2012, but globalization then began to stall, the share of exports in global GDP started to fall, and opponents of freer trade have taken power in key countries (most notably the United States and the United Kingdom), suggesting that the policies that fostered globalization may change in the future.

COVID-19 may have accelerated this trend. Although the pandemic is a global phenomenon, leaders have made major decisions about how to fight it—in both health and economic policy—on a country-by-country basis. The most striking examples of this are the US withdrawal from cooperation in the World Health Organization, and the unilateral decisions of both China and Russia to deploy their own vaccines before completing testing. In the midst of the pandemic, the US-China trade war shows no sign of abating. And almost immediately after the adoption of the USMCA trade treaty for North America, the United States imposed tariffs on Canadian aluminum. That’s not a good sign for the future of international cooperation and continued open borders.

It’s likely that President Biden will move quickly to reduce trade tensions, especially with traditional allies. The president does not need congressional approval to remove or reduce tariffs imposed by the previous administration. But Biden’s campaign position papers suggest that the new administration will likely tamp down the traditional free-trade emphasis of previous Democratic presidents such as Clinton and Obama.10

Businesses are likely to respond to the recent trade policy volatility. One important question is whether businesses will rebuild their supply chains to create more resilience in the face of shocks such as the pandemic and the change in US trade policy. It’s impossible, of course, to simply and quickly refashion supply chains to reduce foreign dependence. American companies will continue to source from China in the coming years. But companies will likely begin to reduce their dependence on foreign suppliers, or attempt to have a portfolio of suppliers rather than a single source, even if the single source is the cheapest.

Reengineering supply chains will inevitably mean a rise in overall costs. Just as the “China price” held inflation in check for years, an attempt to avoid being dependent on China might create inflation pressures in the later years of our forecast horizon. And if markets won’t accept inflation, companies will have to accept lower profits in order to diversify supply chains. Globalization has offered a comparatively painless way to improve most people’s standard of living; deglobalization will involve painful costs and limit real income growth during the recovery.

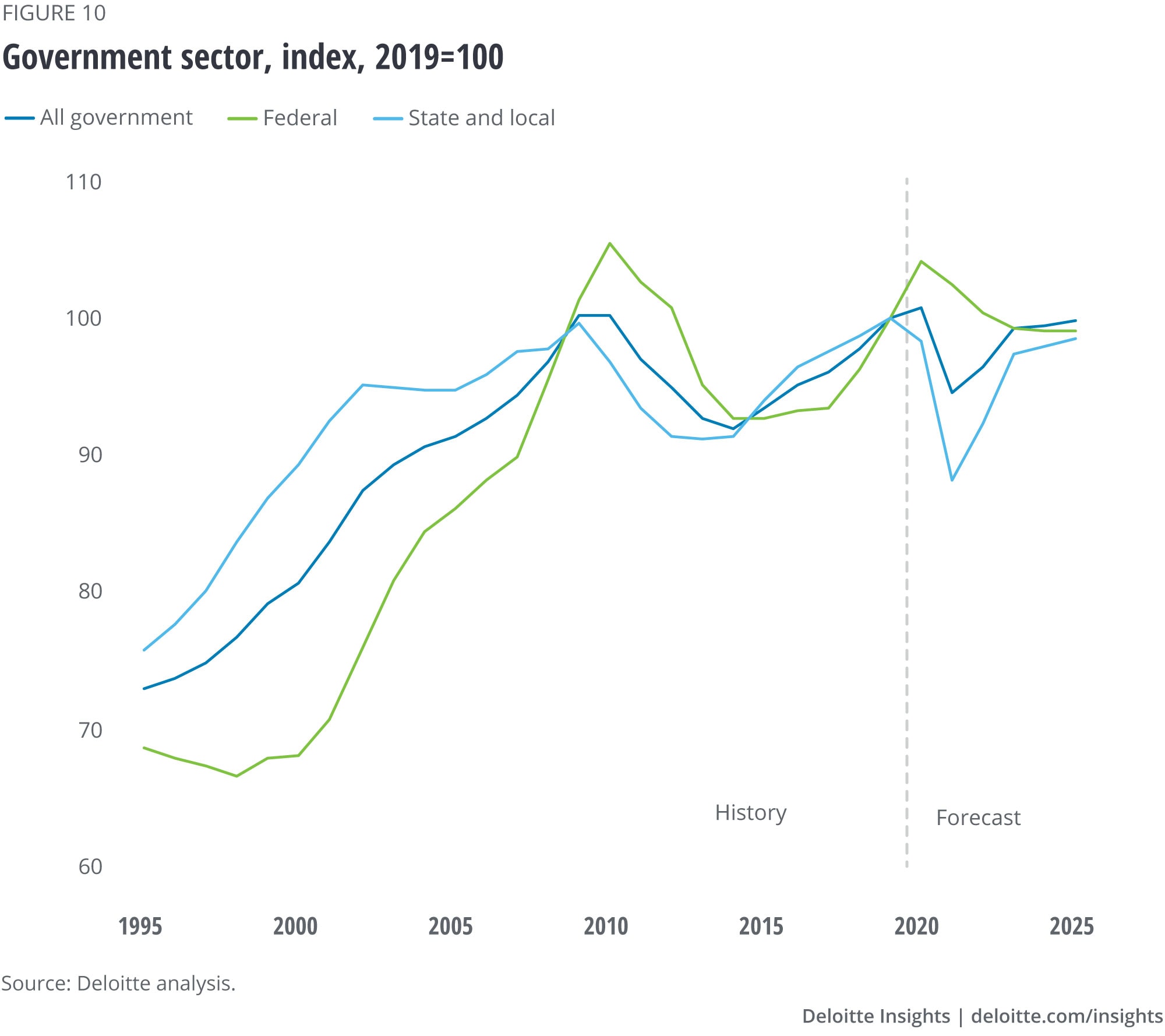

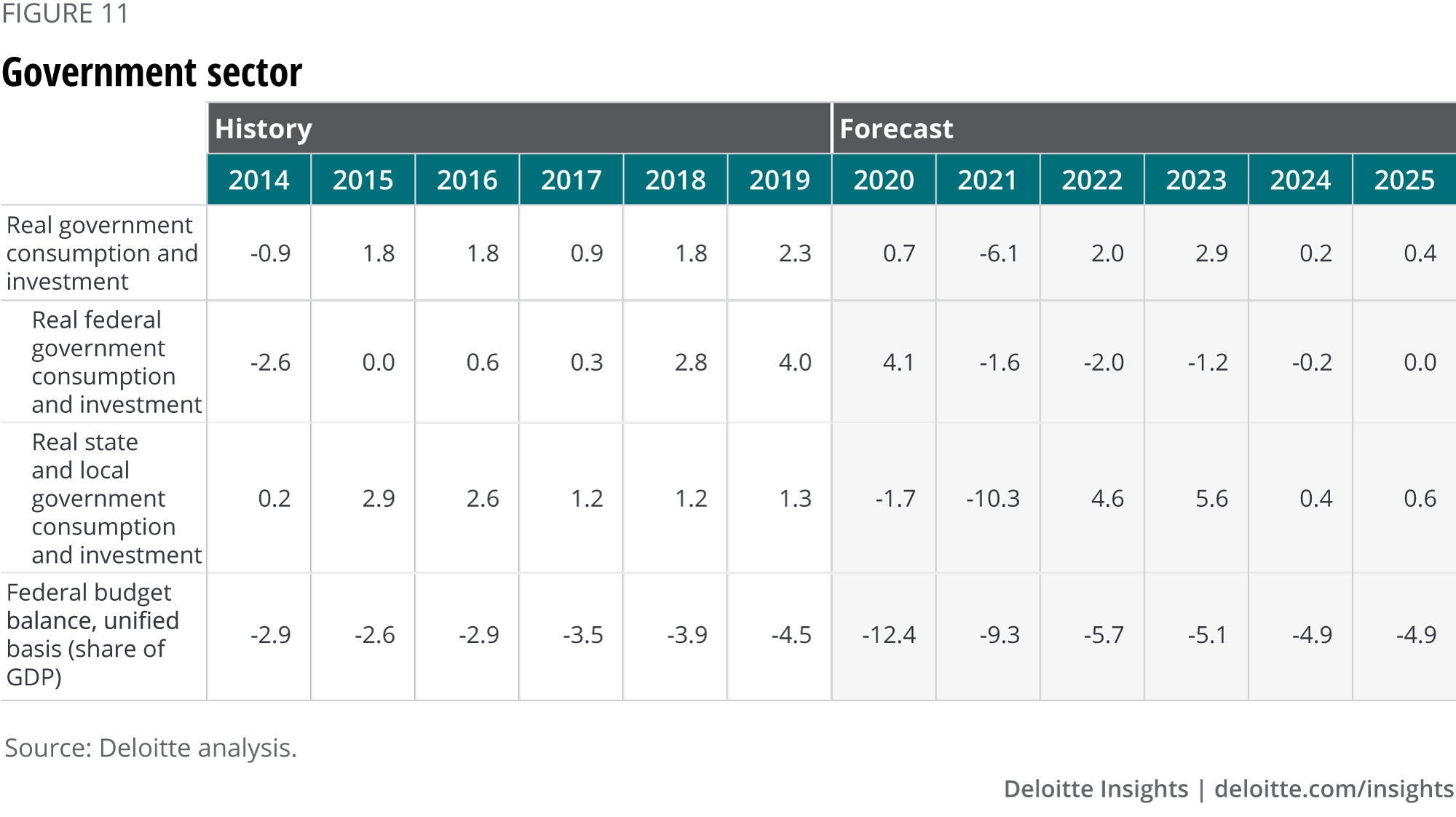

Government

There are two key policy questions for the short- and medium-term economic forecast: Will the federal government deliver another significant relief package by early 2021, and what form might a new stimulus bill take? Following Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell,11 we think it is important to distinguish between relief measures that prevent the economy from worsening during the pandemic and stimulus measures designed to help the economy reach full employment when the pandemic is over.

A well-designed relief bill would address three main issues:

- Extended unemployment benefits, and unemployment benefits for gig workers, will stop in January. This is on top of the loss of the US$600 unemployment insurance supplement in July. More than 20 million people are receiving unemployment insurance, and many will lose their incomes if the expansion of unemployment benefits does not continue.

- State and local governments face a significant funding problem. The decline in economic activity has translated into a decline in tax collections. Since state governments cannot run deficits, without federal aid they may need to accelerate the budget-balancing layoffs and program shutdowns they have already begun.12

- State governments will need financial help for managing COVID-19–related spending and, especially, for deploying vaccines as they become available.13

As of the end of November, the chances of a significant lame-duck relief bill passing seem slim. Once the new Congress is seated, a new approach is possible, though most Senate Republicans are on record opposing significant state and local aid, and it’s unclear whether they would allow an extension of unemployment benefits to become law. This creates a significant risk that Congress will be unable to pass a relief bill substantial enough to at least partially address the problems outlined above.14 Our baseline assumes that Congress passes a scaled-down version of a relief bill in January or February, and that state and local governments are forced to shed about 2 million jobs in early 2021.

The need for stimulus depends on how well policy has “frozen” the economy. Several features of the current recession suggest that postpandemic growth could be quite rapid:

- Banks remain well capitalized; the financial system is operating normally.

- Many businesses remain financially healthy and able to borrow and spend to expand capacity when demand picks up.

- Layoffs have been concentrated among lower-skilled workers. While this has unfortunately concentrated the economic impact of the pandemic on those least able to manage, rehiring can take place quickly once demand recovers.

On the other hand, there are reasons to expect the economy to require additional aid:

- Permanent changes in demand (for example, less business travel and entertainment) may leave the economy at less than full employment during a long adjustment period.

- These permanent changes may also leave capital stranded—invested, for example, in a surplus of aircraft if travel does not recover. Essentially, the economy would suffer a significant depreciation of its capital stock.

- Workers who suffer longer spells of unemployment find it harder to return to work.15

Our baseline assumes that—after an initial acceleration as vaccines are deployed in mid-2021—economic growth is relatively slow. Under those conditions, a stimulus (which we have not assumed) would be useful. Our fast return scenario assumes that economic growth is much faster, and the economy quickly returns to full employment, even without a major stimulus bill. Once we are at the stage of deploying the vaccine, policymakers will need to determine whether further stimulus is necessary.

If the economy does indeed need that boost, the stimulus package’s composition will dictate its effectiveness. The Congressional Budget Office suggests that the multiplier, or bang for the buck, of federal spending on GDP is higher from direct federal spending, or transfers to state and local governments, for infrastructure than for tax cuts.16 An effective stimulus will likely focus on those areas.

Relief spending thus far has ballooned the budget deficit. The CBO expects federal debt held by the public to equal over 100% of GDP by the end of FY2021. The Deloitte baseline shows the annual federal deficit remaining at over US$2.4 trillion through 2025, the end of our forecast horizon; this is larger than the largest deficit run during the global financial crisis.

This inevitably raises the question of whether the US government can continue to borrow at such a pace. The answer is that it can—until investors lose confidence. At this point, investors show no sign of concern about US debt. In fact, very low interest rates on US government debt indicate that the world wants more, not less, American debt. We anticipate no problem over the forecast horizon. But the government will face a crisis if it does not eventually find ways to reduce the deficit and consequent borrowing. That crisis may be many years away, and current conditions argue for waiting. It would be a bad idea to wait too long once those conditions lift.

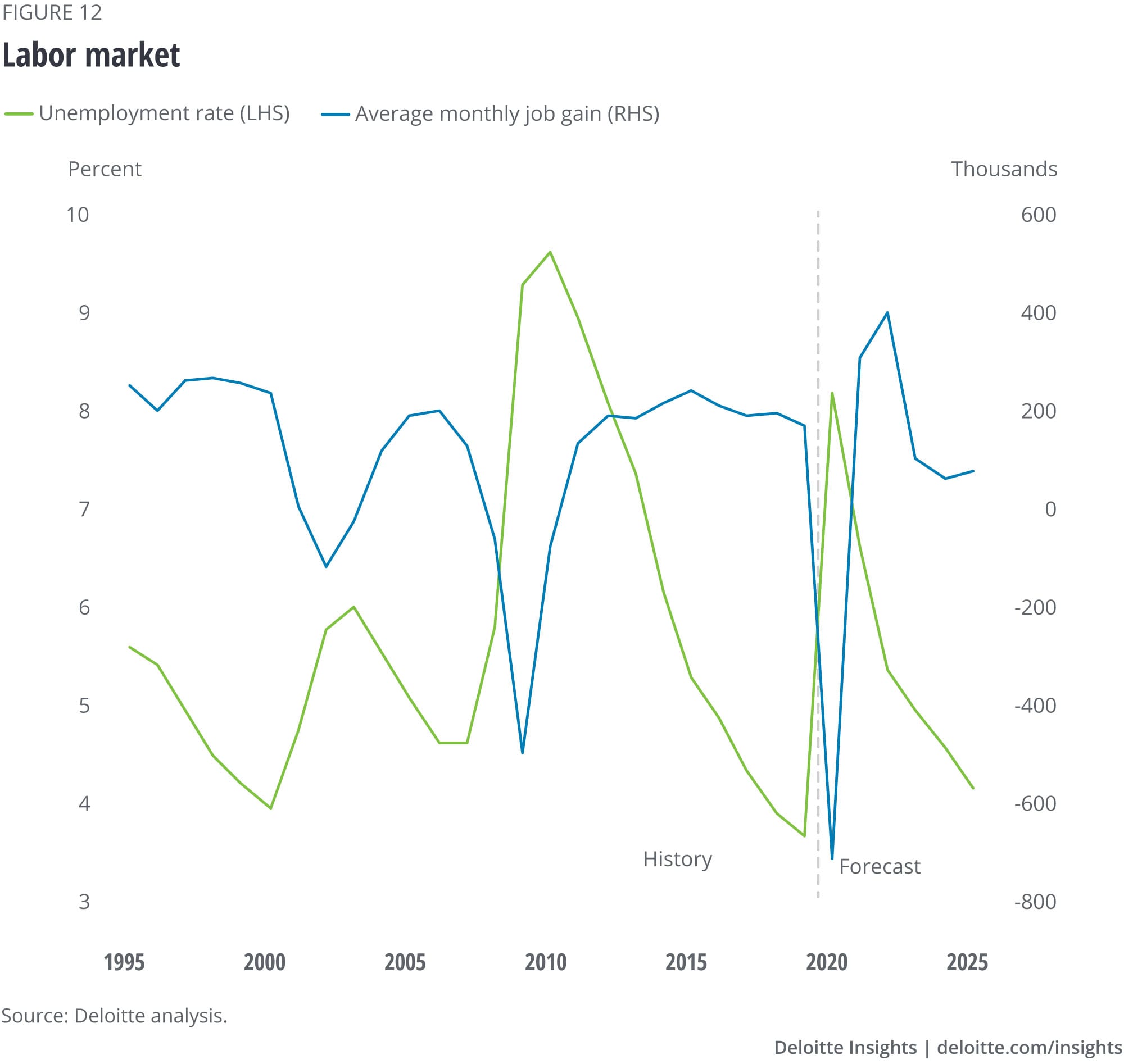

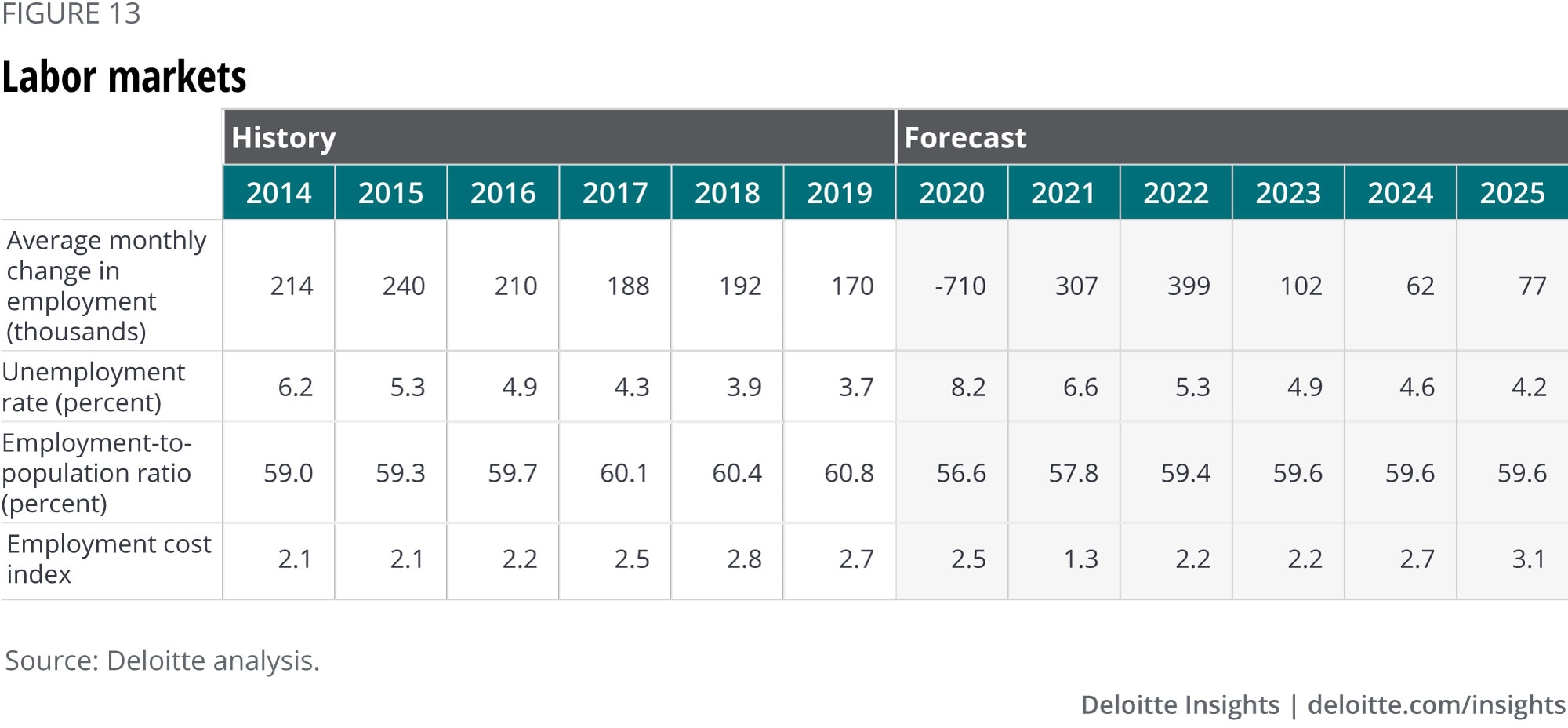

Labor markets

The great layoff of April 2020 saw employment plunge by more than 20 million, with most industries suffering a decline of more than 10%. Employers laid off half of everyone working in arts, entertainment, and recreation and in food services and accommodation. That’s a massive hole. About half of those jobs have returned, but employment remains about 10 million below the prepandemic level. And the big employment gains may be at an end.

- As long as the disease remains a significant issue, demand in the most affected industries will continue to lag.

- Without a relief bill, many industries will feel the drop in spending, from both lower unemployment benefits and state and local layoffs.

- The disease remains a potent problem in the very short run. The number of new daily COVID-19 cases in the United States neared 150,000 by the end of November—with almost 100,000 people hospitalized—prompting authorities in a number of states to call for reinstating restrictions on, for example, restaurant and bar operations. Until the caseload begins to fall, both official restrictions and people’s fear of the disease will put a lid on economic activity.

In the longer term, businesses will still be looking for people—but perhaps in different industries and occupations. Efforts to reshore parts of the supply chain, and to build more robust manufacturing systems, will likely mean that jobs will become available in manufacturing and related industries. How to entice people to switch to manufacturing from, say, food service, and accommodation? The lack of opportunities in the old areas will help, but many businesses in manufacturing may need to invest substantial effort—and perhaps higher wages—to attract workers, even as unemployment remains high.

Such labor market adjustments are usually slow to occur, one reason why we expect the overall economic recovery in the baseline to be relatively slow. Promoting more efficient labor markets might help to speed the recovery—but it would mean admitting that the prepandemic economy will never return. That might be a hard pill for workers, businesses, and policymakers to swallow.

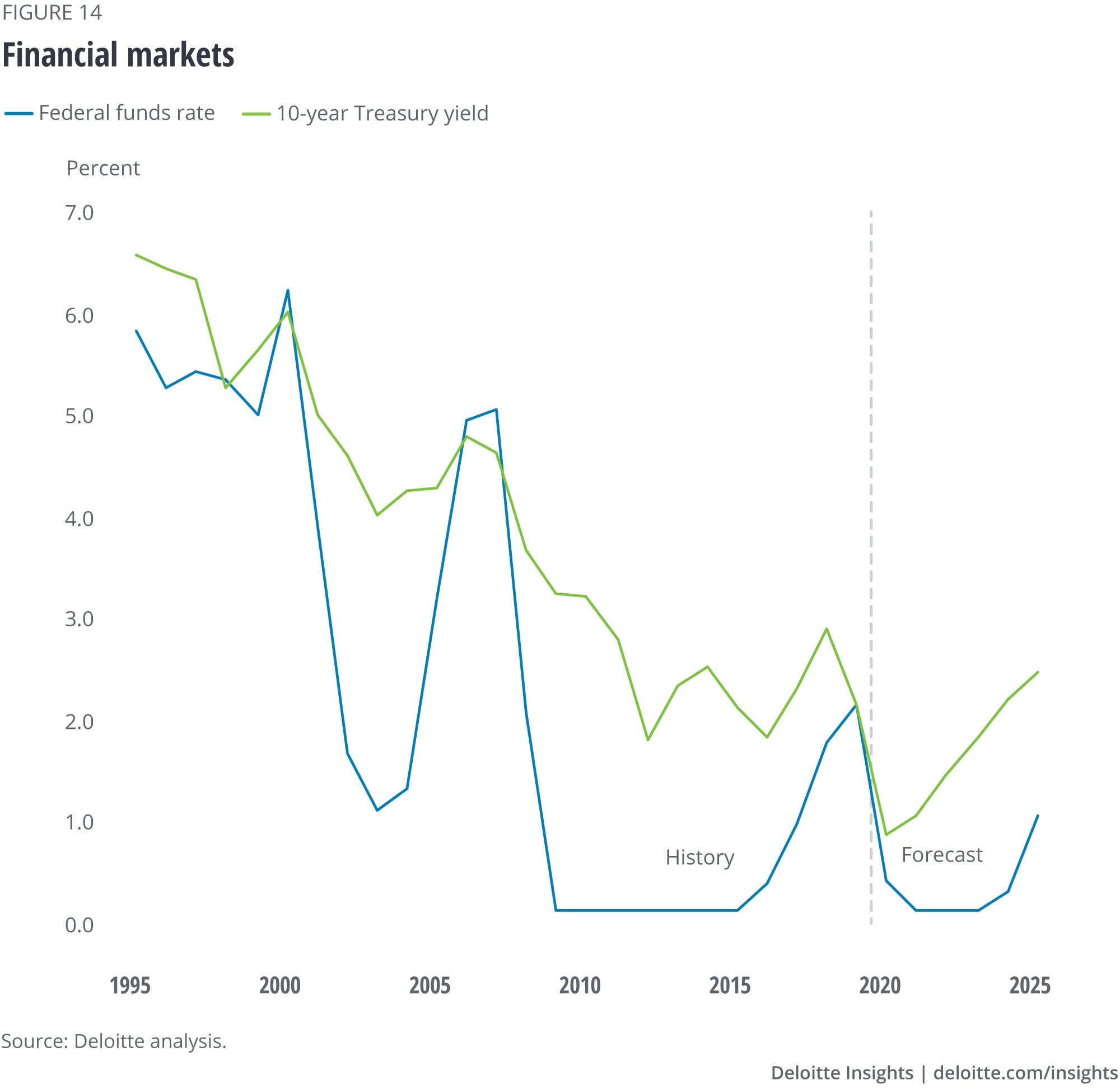

Financial markets

The Fed’s operations have been one of the bright spots of the response to the pandemic. When the disease first began spreading in the United States, there was a significant possibility that a financial market meltdown would exacerbate the country’s economic problems. The Fed’s prompt and strong actions kept financial markets liquid and operating, preventing that additional level of pain.

There was a cost, of course: the Fed’s intervention in many different markets. The traditional concerns about the Fed buying private assets have gone out the window, and the Fed has created methods for direct lending from US states, counties, and cities (Municipal Liquidity Facility), small and medium-sized businesses (Main Street Lending Program), and purchases of corporate bonds (Primary and Secondary Corporate Credit Facilities).17 This is unprecedented: The Fed has traditionally avoided lending directly, avoiding the complications of dealing with nonfinancial firms. Other programs are aimed at stabilizing specific financial markets. Although the volume of lending for many of these facilities is still at a small fraction of the announced level, the Fed’s willingness to lend has calmed credit markets.

But there is a limit to what the Fed can do. The Fed can keep financial markets operating, provide liquidity for markets, and even lend directly to companies so that they don’t shut down. But it can’t maintain the incomes of unemployed people, or lend to state and local governments, or fund necessary health care spending. That’s why Fed Chairman Jerome Powell has emphasized the importance of action by Congress and the president.18 As he points out, the Fed has “lending, not spending, powers.” It would be foolish to expect Fed action alone to solve this economic crisis.

In the longer term, the Fed will want to wean markets off of its aid. But this is likely several years away. And since sales of these assets will precede hiking the Fed funds rate, we have assumed that the funds rate remains near zero over the five-year forecast horizon. We do assume a slow rise in long-term interest rates as financial markets “normalize.” But that leaves the 10-year Treasury yield at 2.5% by 2025. Interest rates are always the least certain part of any forecast: Any significant news could, and will, alter interest rates significantly.

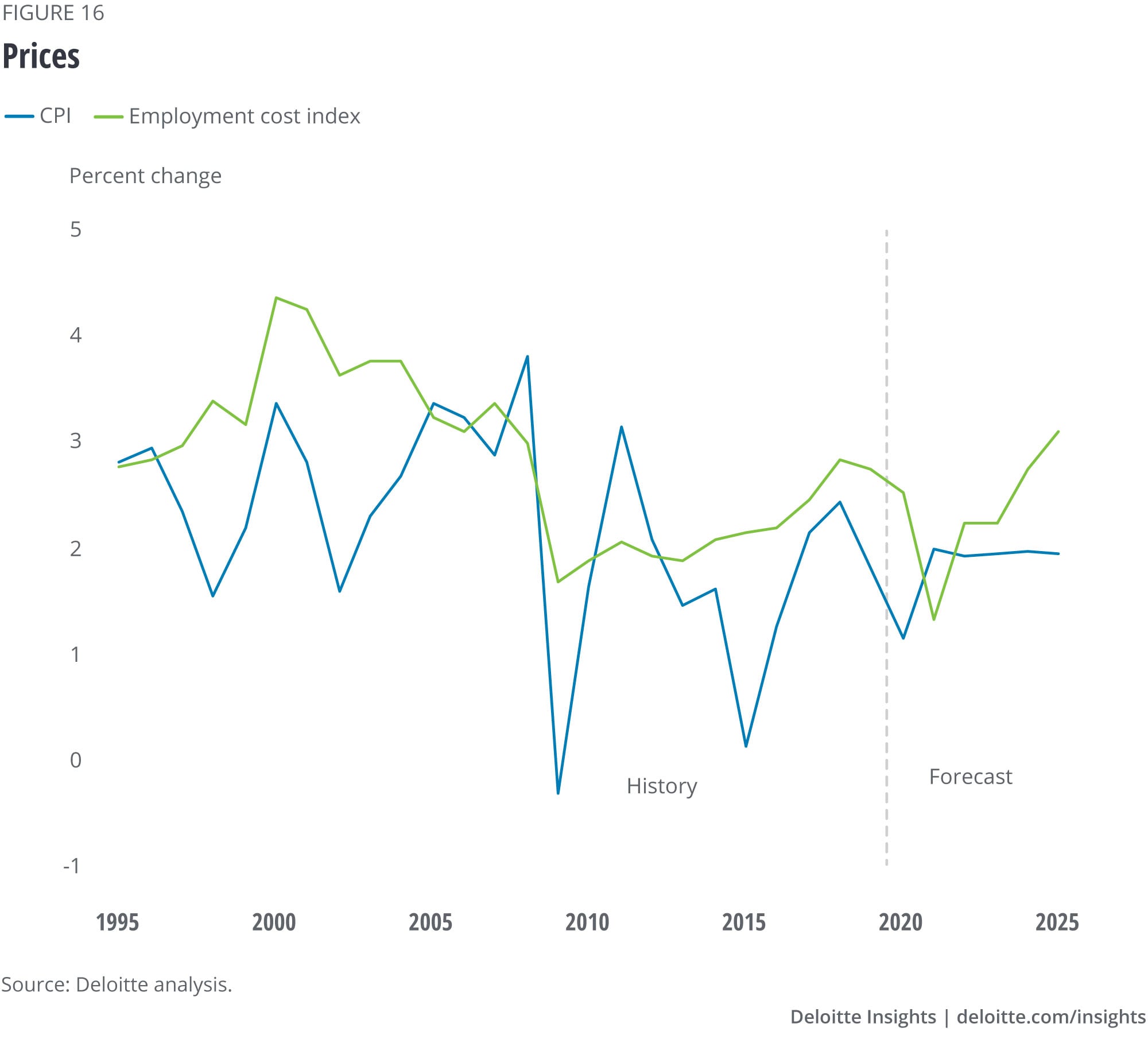

Prices

Shutting down much of the US economy to fight COVID-19 might be expected to raise prices, with supply chains strangled. And it might be expected to lower prices, with consumer demand crashing. Which has happened?

The supply shock of the pandemic has clearly raised certain prices. The Consumer Price Index (CPI) for food at home rose 4% in the second quarter as supply chain problems caused spot shortages for consumers—with some reversal afterwards as things settled down.

That’s a short-term impact, but there may be some significant long-term impacts. For example, requirements for cleaning and social distancing will likely raise prices of restaurant meals, airplane travel, schooling, and many services—such as day care—over the next year.

Companies in areas such as these will not only be faced with higher costs—they will lose the ability to exploit economies of scale. Added to that, businesses are likely to adopt practices such as larger inventories to reduce their vulnerability to shocks. Those practices will also raise prices—and reduce productivity.

On the other hand, the demand shock has begun to drive down some prices. That’s been most evident in energy, where the CPI in October was over 9% below the previous year’s level. Gasoline prices of about US$2.25 per gallon over the past few months might have made for happy motorists, except that miles driven is also down—in fact, that has been a key driver of low gasoline prices. In the baseline forecast, we expect overall demand to remain low, both because of the pandemic and because so many people are out of work. That will likely result in some significant discounting over the next year.

The battle between supply and demand will likely continue through the forecast horizon. In a world of high unemployment, businesses will have little pricing power but will face higher costs. Given these offsetting factors, the baseline forecast calls for inflation to continue at about 2.0% over the forecast horizon.

Appendix

More from the Economics collection

-

Chain reaction Article3 years ago

-

Monetary policy in Asia Article3 years ago

-

Federal Reserve monetary policy in the time of COVID-19 Article4 years ago

-

State of the US consumer: October 2024 Article3 weeks ago

-

G7 economies Article4 years ago