China’s investment management opportunity Reforms could create a multitrillion-dollar market for foreign firms

14 minute read

13 November 2019

China's reforms have opened a $30.2-trillion opportunity for foreign investment managers. To win in this complex market, foreign firms should develop segment-specific strategies, alternative data capabilities, and partner with online wealth platforms.

Key takeaways

- The Chinese government is reforming the country’s pension system, capital markets, and investment management industry as a part of a bigger plan to curb an anticipated retirement savings deficit.

- Foreign investment managers have the opportunity to play a greater role in the tightly regulated industry, potentially managing a sizeable chunk of the US$30.2-trillion addressable retail financial wealth by 2023.1

- Foreign firms looking to enter the market should develop investor segment-specific strategies, alternative data capabilities, and partner with online wealth platforms to achieve success.

China: Investment management’s next big opportunity

With the Chinese government set to eliminate restrictions on foreign ownership of fund management firms in 2020, many investment managers worldwide are eagerly eyeing China as their next big growth opportunity.2 The potential market is vast: By 2023, the country’s total addressable retail financial wealth is expected to reach US$30.2 trillion, with US$3.4 trillion in retail assets under management (AUM) in Chinese publicly registered funds.3

Learn more

Explore the Financial services collection

Visit the Asia Pacific economics collection

Subscribe to receive related content

Download the Deloitte Insights and Dow Jones app

But these market size statistics—enticing as they may be—don’t guarantee success for any particular firm. The future of investment management in China could largely depend on its prospects for economic growth, the reliability of regulatory reforms, and the spread of cultural changes that accompany individual economic prosperity. Investment managers hoping to expand to China should, therefore, consider a host of marketplace, regulatory, and cultural complexities as they establish a foothold and pursue market share. This article explores some of these complexities, aiming to arm investment management company leaders with insights to help them plan for what might lie ahead.

China’s retirement savings dilemma

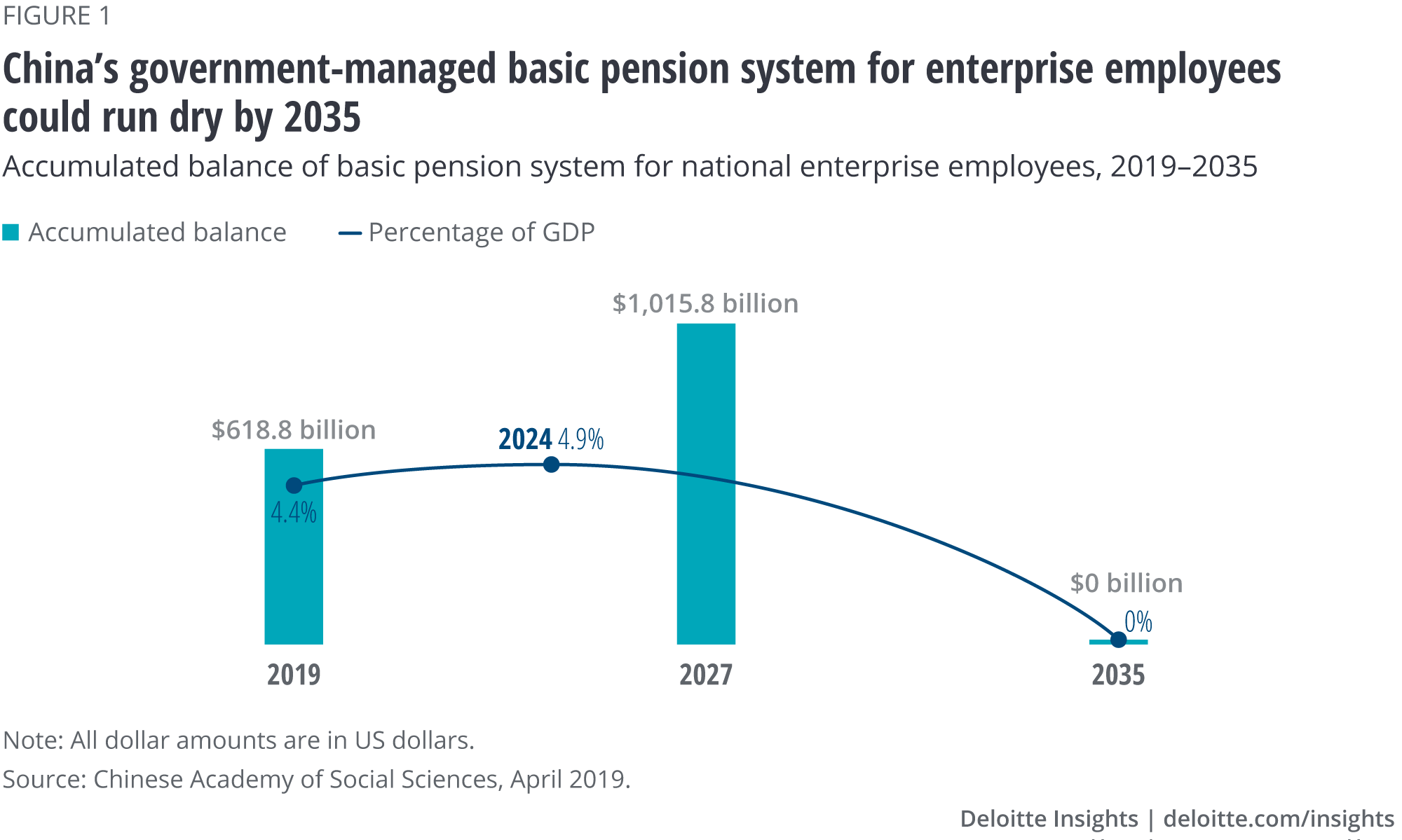

China’s recent regulatory reforms to encourage foreign firms to enter the investment management market, while perhaps complex, could be due to pensions. The recent relaxation of policies around foreign ownership of investment managers is part of a broader effort by the government to curb a looming retirement savings deficit. Forecasts by the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences (CASS) predict a significant retirement savings gap developing in China over the next 30 years.4 In fact, the China pension actuarial report 2019–2050 estimates that the assets of the government-run Basic Pension System for Enterprise Employees could be depleted by 2035, principally due to an unfavorable shift in the ratio of workers to retirees (figure 1).5

China’s recent regulatory reforms to encourage foreign firms to enter the investment management market could be due to pensions.

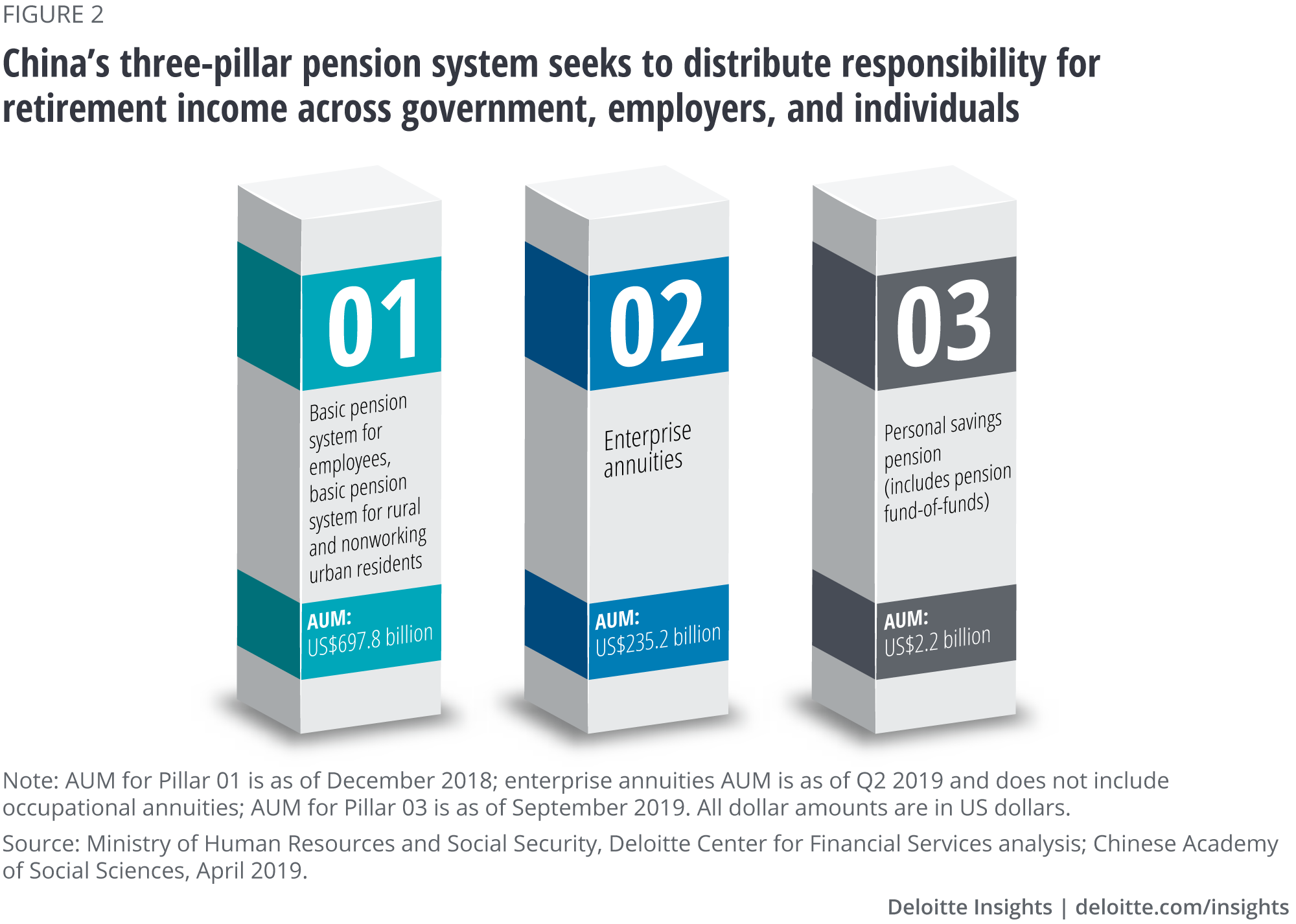

To address this expected shortfall, Chinese authorities appear to be looking to shift more responsibilities for securing retirement income to employers and individuals. The envisioned model is a three-pillar system in which government pensions (the first pillar) could be supplemented by enterprise-driven defined contribution savings platforms (the second pillar) and individual retirement accounts (the third pillar) (figure 2). While the current system relies heavily on the first pillar, China’s recent regulatory changes appear intended to balance the retirement savings load across all three pillars.

The Chinese government seems to be taking steps to drive greater utilization of the system’s second and third pillars. China’s regulators have studied the meaningful growth of the United States’ defined contribution and individual retirement account (IRA) programs in the hope of replicating its success. The United States established 401(k) defined contribution accounts in 1981;6 by the end of 2018, 401(k) plans held US$6 trillion in assets.7 Similarly, since the launch of IRAs in 1975, IRA AUM in the United States has grown to US$8.8 trillion at the end of 2018.8

The growth of IRAs in the United States may provide a fair idea of the AUM growth potential for individual pension products in China, given the country’s increasing appetite for personal wealth-building and the overall growth in investable assets fueled by economic prosperity. In particular, just as in the United States of the 1980s, retirement investments in China may be driven by necessity. IRAs in the United States grew at a time when corporations were shuttering defined pension plans at a rapid pace; the anticipated depletion of China’s government pension fund could prompt similar actions among Chinese individual investors.

The growth of IRAs in the United States may provide a fair idea of AUM growth potential for individual pension products in China.

China seems well placed to serve these investors in terms of fund choice. When the second and third retirement pillars were developed in the United States, the country’s mutual funds numbered about 700, many of them offered by well-respected brands.9 In China, however , there are 5,983 publicly registered funds currently, and many of China’s largest investment managers have already partnered with Western firms.10

If China can replicate the United States’ AUM growth in defined contribution and IRAs, investment managers in China could have an enormous opportunity to gather retirement assets. However, while China already has some of the building blocks in place to accomplish this, encouraging people to invest and enhancing capital market efficiency will likely be a complex task.

The government is working to help capital markets mature

For China’s retirement savings market to grow effectively, its capital markets likely need to mature. Recognizing this, the Chinese government is taking several actions to enhance capital market maturity.

Allowing non-Chinese firms to participate in the country’s investment management activities could be one important step. Non-Chinese firms have recently been allowed to own majority stakes in investment managers with publicly registered funds, and by 2020, the Chinese ownership requirement could drop completely.11 One hoped-for benefit of this move could be to put the market on a more secure, data-based footing. An opinion held by some professional investment managers in China is that rumors play too great a role in securities trading and valuation compared with Western markets, which tend to be more typically driven by data, analytics, and professionalism.12

Allowing non-Chinese firms to participate in the country’s investment management activities could be one important step.

Another step toward enhancing the financial markets’ maturity is the government’s plan to increase market-based financing. This plan has two main prongs. As the first prong, regulators are piloting a streamlined registration-based system for initial public offerings (IPOs) in Chinese markets.13 With a potential increase in IPOs, investors would have access to investments in a broader range of industries and companies. As firms work to differentiate themselves in order to raise capital, they may offer greater transparency into corporate operations, which can also reduce rumor-driven investing. The second prong restricts the offering of investment products with guaranteed returns by Chinese banks.14 This could push investors to use market-based products to build their investment portfolios, helping shift investment risk to the investor instead of the banking system.

The drive to encourage market-based products highlights a significant change regarding risk, reward, and responsibility that appears to be taking place in China. Market-based products are managed and represent a shift of risk and revenue from the banking sector to the investment management sector. In the initial stages of this shift, most Chinese investors are opting for more money market and bond funds than equity funds.15 In fact, the current investor preference for fixed income and money market funds has recently stifled profitable growth for many investment management firms in China, as these products generate lower management fees. (A few firms, however, have seen notable success, usually driven by scale and efficiency.) As Chinese investors and markets mature, they may potentially allocate a greater share of their investments to equity funds.

Additional opportunities exist for China to encourage individual investing for retirement. For example, while the authorities have approved the launch of individual retirement products, the government has not developed incentives to participate in these accounts. Tax deferral provisions, similar to those in US retirement accounts, could likely be a next move.

An ongoing cultural shift toward an investing mindset is likely to further accelerate the adoption of IRAs. Even China’s mass retail segment appears to be developing an investing mindset, as the country’s fast-growing economy facilitates the generation of financial wealth in the largest segment of the population.16

Sizing the market: Investment funds’ future in China

Asset growth in China has the potential to be even more dynamic than was the case in the United States, given seemingly strong government support, continuing economic growth, and the country’s large population. But how much growth can be expected?

Asset growth in China has the potential to be even more dynamic than in the United States, given seemingly strong government support, economic growth, and its large population.

To find out, we built a model to estimate China’s future retail financial wealth. For the purposes of the model, Chinese investors were divided into four segments based on the wealth they possess: mass retail, cream of mass retail, mass affluent, and high net worth individuals (HNWI). Of these, the last two segments were deemed similar to Western market segments.

Methodology

This report is based on insights gleaned from on-the-ground discussions with two regulatory bodies and senior executives of a dozen investment management firms in China. We supplemented these insights with a quantitative model that forecasts retail financial wealth using GDP as the explanatory variable. Each investor segment’s assets in public funds are assumed to be proportional to the financial wealth they hold. The bottom 20 percent of the population is assumed to own no financial wealth.

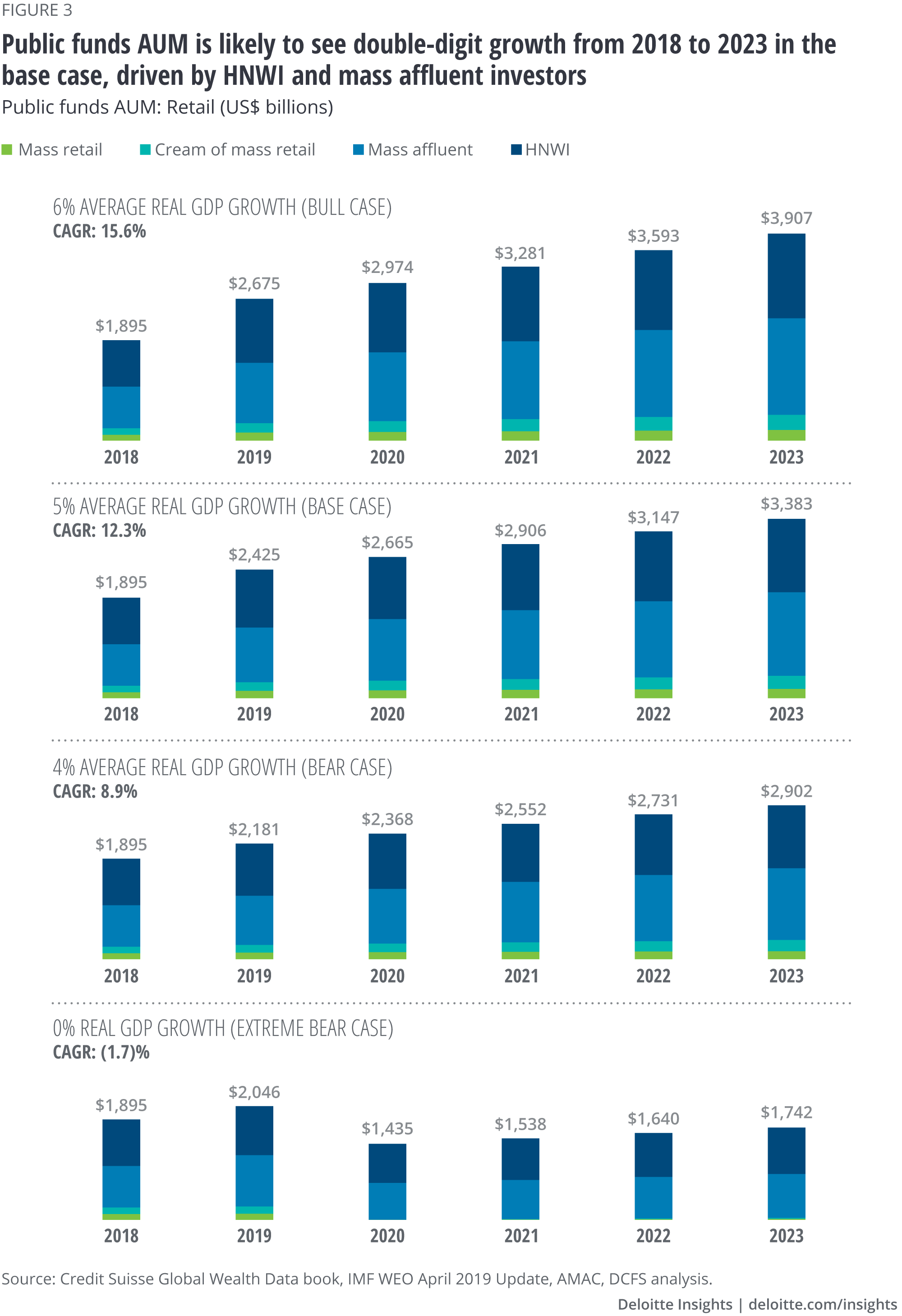

Figure 3 shows the model’s forecasts under four different assumptions for real GDP growth, which is the major driver of these asset growth forecasts. The “base” scenario assumes that China’s GDP will grow by an average of 5 percent annually over the next five years, as our models point to this growth rate as the most likely. (We recognize that China’s GDP has grown at an annual average of 6.9 percent over the past five years. However, as economies get larger, it is typically harder for them to maintain growth levels as high as China has recently experienced.) This base case estimates that retail AUM in Chinese public funds could nearly double to US$3.4 trillion by the end of 2023.

Under different GDP growth assumptions, the model’s forecasts change accordingly. In our extreme “bear” case of zero percent GDP growth, the forecast predicts that public fund AUM will decrease slightly, standing at US$1.7 trillion in 2023. On the other hand, if China’s GDP averages 6 percent growth through 2023, public fund AUM is expected to grow to US$3.9 trillion.

We also modeled asset growth among the four Chinese retail investor segments. Our analysis suggests that each segment will experience healthy asset growth between now and 2023. The highest absolute growth is expected in the mass affluent segment, which could become the largest segment by financial wealth by 2023 (figure 4).

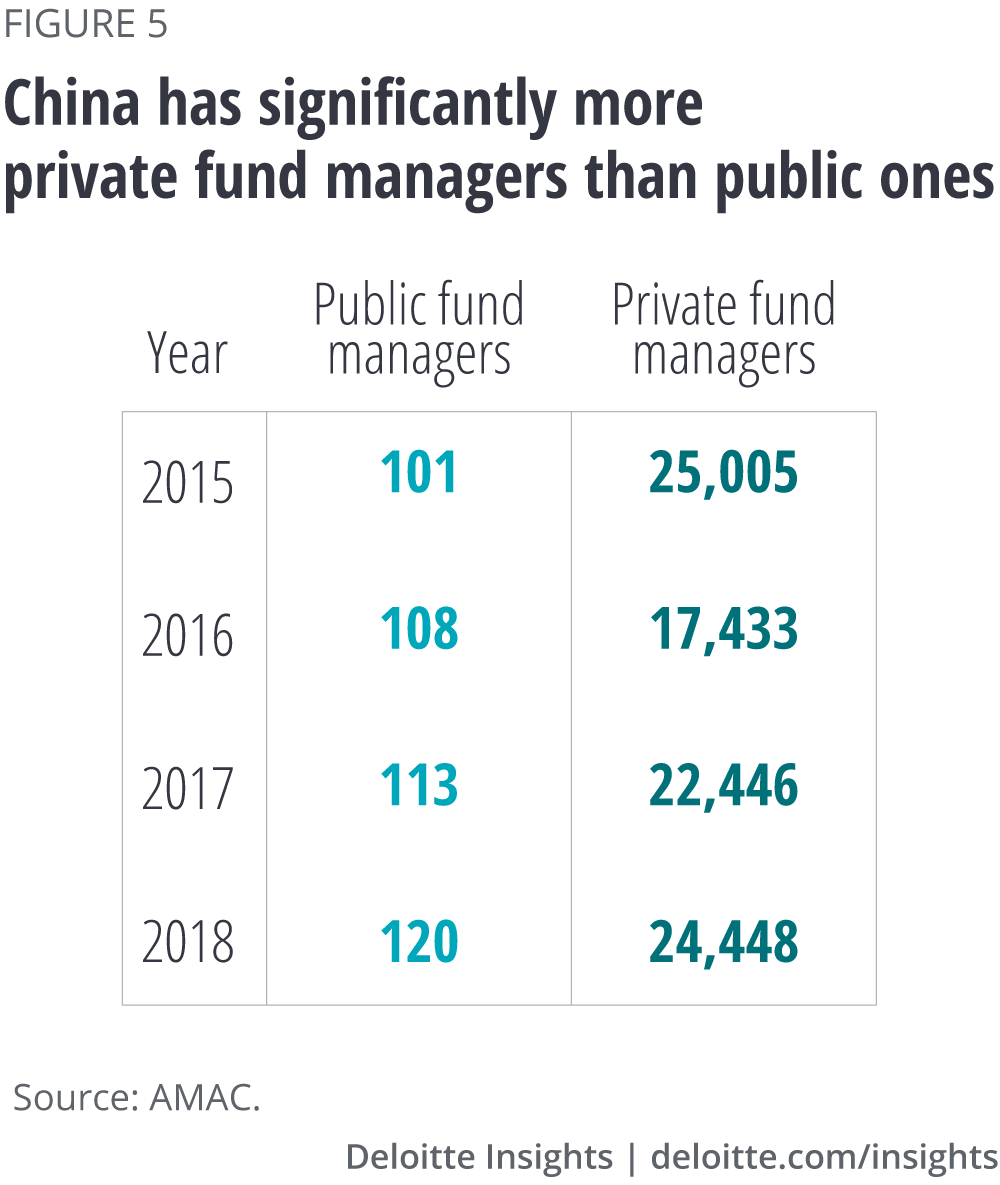

The private fund market is a bit different. Since China has a qualified investor rule, the retail market for private funds comprises HNWI investors alone. This market is even more fragmented than the public funds market, with more than 24,000 private fund managers currently competing for US$1.3 trillion in AUM17 (figure 5). This space could be ripe for consolidation as branded, well-capitalized firms enter the marketplace with efficient operations and scale.

AUM in private funds could have a growth rate similar to that of public funds in the base case and may reach nearly US$2 trillion at the end of 2023 (figure 6). This growth rate is faster than that of China’s GDP in this scenario, as investors across segments could allocate more of their wealth to financial assets.

To sum up, the future could be bright for Chinese investors—thanks, in part, to the Chinese investment management industry’s progress toward the development of an investment culture, even prior to the recent reforms. China’s investment management industry didn’t spring up overnight. It comprises nearly 6,000 publicly registered funds that have accumulated US$1.9 trillion in assets as of June 2019.18 China’s policy changes—including the shift to the three-pillar retirement system along with reforms to capital markets and foreign investment management firm participation—may further unlock the potential of the country’s large, existing foundation of investments by feeding them with much-needed AUM. Higher industry AUM levels can enable firms to reinvest in asset-gathering, potentially creating a virtuous cycle of retirement savings.

Higher industry AUM levels can enable firms to reinvest in asset-gathering, potentially creating a virtuous cycle of retirement savings.

Will these reforms alter the course of retirement savings enough to reduce or eliminate the retirement savings gap in China? They certainly encourage movement in the right direction. Most notably, our projections for growth in retail AUM in both public and private funds far exceed the current balance of China’s government pension fund. A change of this magnitude will likely make a difference in the long-term path to retirement savings.

Pursuing success in China’s investment management market

To succeed in the Chinese investment management market—with “success” defined as profitably raising AUM—firms should understand the Chinese market and investors’ mindsets and expectations and formulate their strategies and offerings accordingly. Here are some steps they can consider:

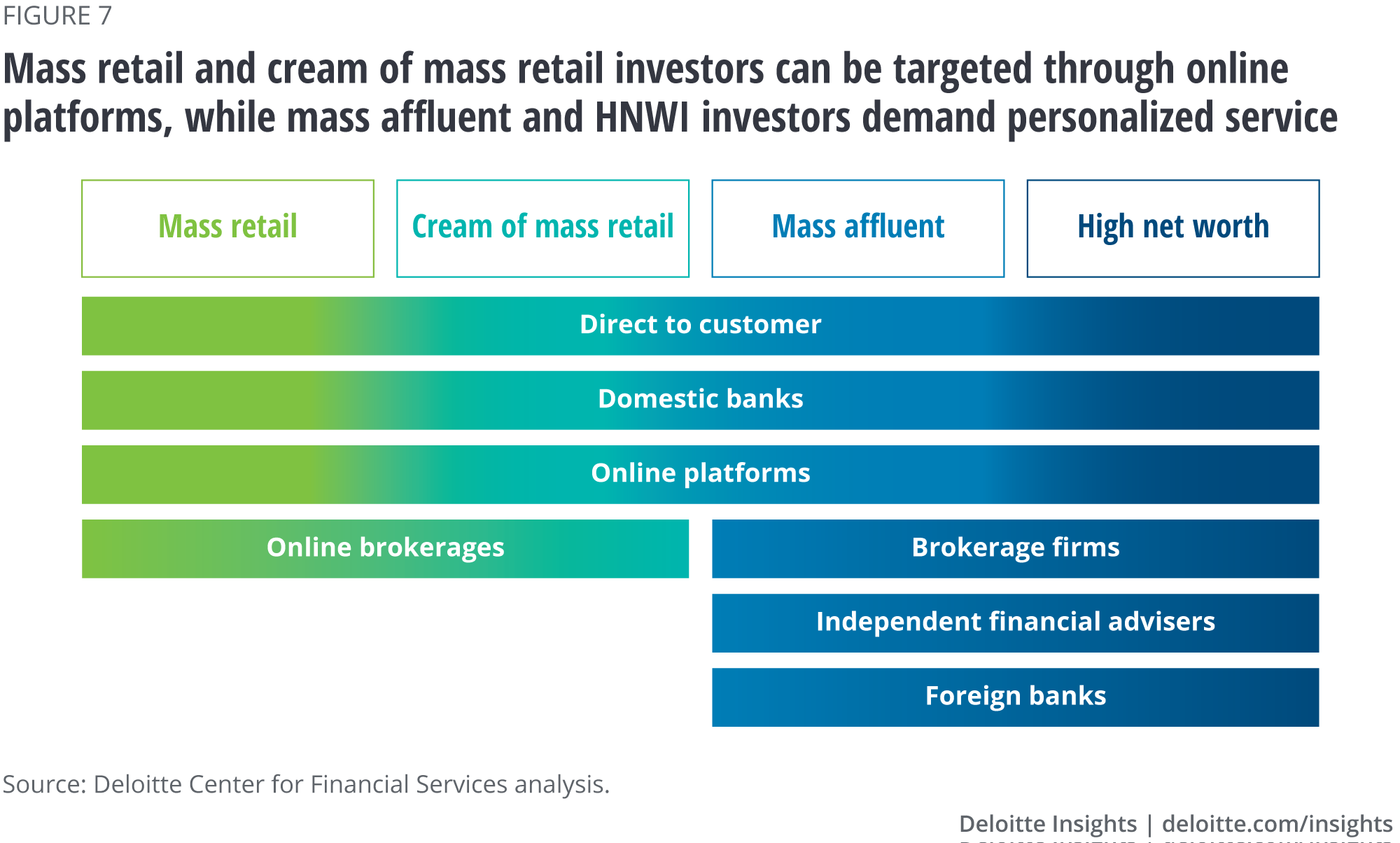

Double down on segment-specific tactics. In the Chinese retail market, segment-specific tactics can potentially drive success to a greater degree than in Western markets (figure 7). For example, for firms serving the HNWI and mass affluent segments—which, together, are expected to have US$2.1 trillion AUM in public funds and US$1.5 trillion AUM in private funds by the end of 2019—the avenues to success may be similar to what works in the rest of the world. Investor preferences among the Chinese HNWI and mass affluent segments are subtly different from those of Western investors, but the distribution points to connect with them are similar. On the other hand, the scale of the Chinese mass retail segment, which includes more than 600 million people, dictates a highly segment-specific approach. Profitably reaching that many investors might call for tactics unique to the Chinese market.

Worth a special mention are the cream of mass retail and mass retail segments, which currently represent an approximately US$300 billion opportunity in public funds AUM. Finding a solution for these two segments is likely more important than this US$300 billion figure might dictate on its own. The cream of mass retail and mass retail segments represent approximately 750 million people, and their well-being in retirement is an important consideration. Helping them invest to achieve their retirement goals is what may be largely motivating investment reforms in the first place. If this is so, then foreign firms that include these segments in their strategic approach are likely to be playing in the solution space that will bring them the most goodwill in the region.

Firms may also benefit from taking a longer-term view of the mass retail and cream of mass retail segments’ profitability potential, even though they might not command the highest margins today. In particular, firms targeting these two segments have an opportunity to control shelf space and build relationships with potentially hundreds of millions of investors through defined contribution platforms (the second pillar). It is quite possible for the second pillar to be a farm system for the next generation of affluent investors. Several firms in Western markets, in fact, have successfully used this strategy to gather assets with low-balance workplace investors through defined contribution platforms.

Firms targeting the cream of mass retail and mass retail segments have an opportunity to control shelf space and build relationships with hundreds of millions of investors through defined contribution platforms.

Partner with established Chinese e-commerce platforms. China has a unique opportunity with the cream of mass retail and mass retail segments, in terms of the number of investors, ticket size, and investment preferences. Gaining access to these segments likely requires a low-cost approach. Fortunately, there are several fund distribution platforms in China with the scale and reach required to efficiently provide investment management services to these segments. Because creating a new, competing platform in China might not be feasible for many investment management firms, investment managers planning to serve these segments should consider seeking placement on these established platforms. The scale of these networks makes possible a favorable combination of customer acquisition cost, recurring customer revenue, and ongoing account-based costs. Hence, placement on these platforms could be an investment manager’s best opportunity to tap into the third pillar of retirement savings for Chinese mass retail and cream of mass retail investors.

That said, a defined contribution platform could be feasible, servicing the same retail segments through the workplace. Since defined contribution platforms are investment-focused and limited in scope compared with e-commerce platforms, an adapted Western platform may be an effective approach to bring this capability to China. Tight coordination with Chinese regulators will likely be key to success in this closely watched, developing retirement savings avenue.

Deliver on investors’ risk-and-return portfolio expectations. One success factor addresses the possibility that Chinese investors, who are known to be risk-takers, may benefit from a greater appreciation for professional risk management in investing. Chinese investors may need more and different guidance on determining the appropriate level of risk and the relationship between risk and expected returns. The investment managers most likely to succeed will likely be those that support these investors in shaping their behavior to optimize their portfolios for risk and reward.

Base investing decisions on alternative data. Meeting Western investors’ risk and return portfolio expectations is difficult enough. In China, it will likely be even harder, as firms must consider factors related to the reform process and the accompanying maturation of both Chinese investors and capital markets. Further complicating the picture, the markets in China are often considered less efficient and transparent than Western markets. And as is widely recognized, macroeconomic reporting in China is largely directional and indicative, but sometimes lacks precision.19

To account for these factors, investment management firms in China should consider building internal capabilities to measure economic and corporate activity in addition to analyzing secondary research . Successful managers in China will likely develop proprietary insights with privately sourced or even proprietary data. Alternative data capabilities to measure consumer, corporate, and macroeconomic activity could thus be more critical than in Western markets. (Firms are leveraging alternative data like satellite imagery, freight traffic, and discretionary spending as they try to outperform market benchmarks.)20 Firms that depend on analyses fueled solely with secondary research and widely reported data are less likely to be successful.

Successful managers in China will likely develop proprietary insights with privately sourced or even proprietary data.

Capitalize on market inefficiency. The first wave of foreign investment managers in China have an opportunity to improve market efficiency by developing mechanisms that create the economic insights needed to manage portfolios in line with investor expectations. As the markets mature and more trading decisions are backed by robust institutional analysis, investors in these early established portfolios stand to reap the benefits and lead the way in China’s nascent, fast-developing capital markets.

Investment managers have a unique opportunity to expand their global footprint into China in the next year or two . While there are undoubtedly many paths to success, all players in China’s complex investment management market will need to find innovative ways to understand and serve this complex, growing market. Firms that move boldly with well-formulated, segment-specific market entry strategies have the chance to capture a lasting advantage.

More from the Financial services collection

-

2025 commercial real estate outlook Article3 months ago

-

Executing the open banking strategy in the United States Article5 years ago

-

Modernizing insurance product development Article5 years ago

-

Achieving gender equity in financial services leadership Podcast5 years ago

-

Fair valuation pricing survey, 17th edition, executive summary Article5 years ago