2021 banking and capital markets outlook Strengthening resilience, accelerating transformation

32 minute read

03 December 2020

In our 2021 banking and capital markets outlook, 200 industry leaders weighed in on their companies’ COVID-19 recovery efforts. How can the emerging lessons serve as a catalyst for business transformation?

As new regulatory trends make an impact in the financial services marketplace, how can your organization remain resilient? Our 2021 regulatory outlooks explore key issues that could have a significant impact on the market and your business in 2021.

Subscribe now to receive your digital copy of the reports as soon as they are live.

Key messages

View sections

Redefining the art of the possible in a post-COVID-19 world

The banking industry’s collective response to the pandemic thus far has been notable. It was no easy feat to go fully virtual and execute an untested operating model in a matter of weeks. Despite some hiccups, many banking operations were executed smoothly. Customers were served, employees were productive, and regulators were reassured. Banks effectively deployed technology and demonstrated unprecedented agility and resilience.

Learn more

2021 Financial services industry outlooks

Read the 2021 banking regulatory outlook

Explore all of the 2021 regulatory outlooks

Visit the Within reach? Women in the financial services industry collection

Explore the Financial services collection

Learn about Deloitte's services

Go straight to smart. Get the Deloitte Insights app

More importantly, banks played a crucial part in stabilizing the economy and transmitting government stimulus and relief programs in the United States, Canada, the United Kingdom, Japan, and many European countries, among others. Banks’ healthy capital levels before the pandemic also helped mitigate the negative impacts from the crisis and should pave the way for the global economy to thrive in the future.

For the banking industry, the economic consequences of the pandemic are not on the same scale as those during the Global Financial Crisis of 2008–10 (GFC), but they are still notable. In addition to the financial fallout, COVID-19 is reshaping the global banking industry on a number of dimensions, ushering in a new competitive landscape, stifling growth in some traditional product areas, prompting a new wave of innovation, recasting the role of branches, and of course, accelerating digitization in almost every sphere of banking and capital markets.

Some of these forces were already in motion before COVID-19. Global GDP growth was waning, but the pandemic exacerbated the slowdown. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) expects global GDP to decline by 4.4%,1 or almost US$6.2 trillion in 2020.2 Despite a possible rebound in 2021, global GDP could still be US$9.3 trillion lower than what was expected a year ago. This drastic contraction in the global economy has already meaningfully diminished loan growth and payment transaction volumes. These declines have been largely offset by near-record levels of trading revenues and wealth management fees. But as the pandemic continues, banks will likely be confronted with a greater share of distressed assets on their books.

How bad could it get for banks?

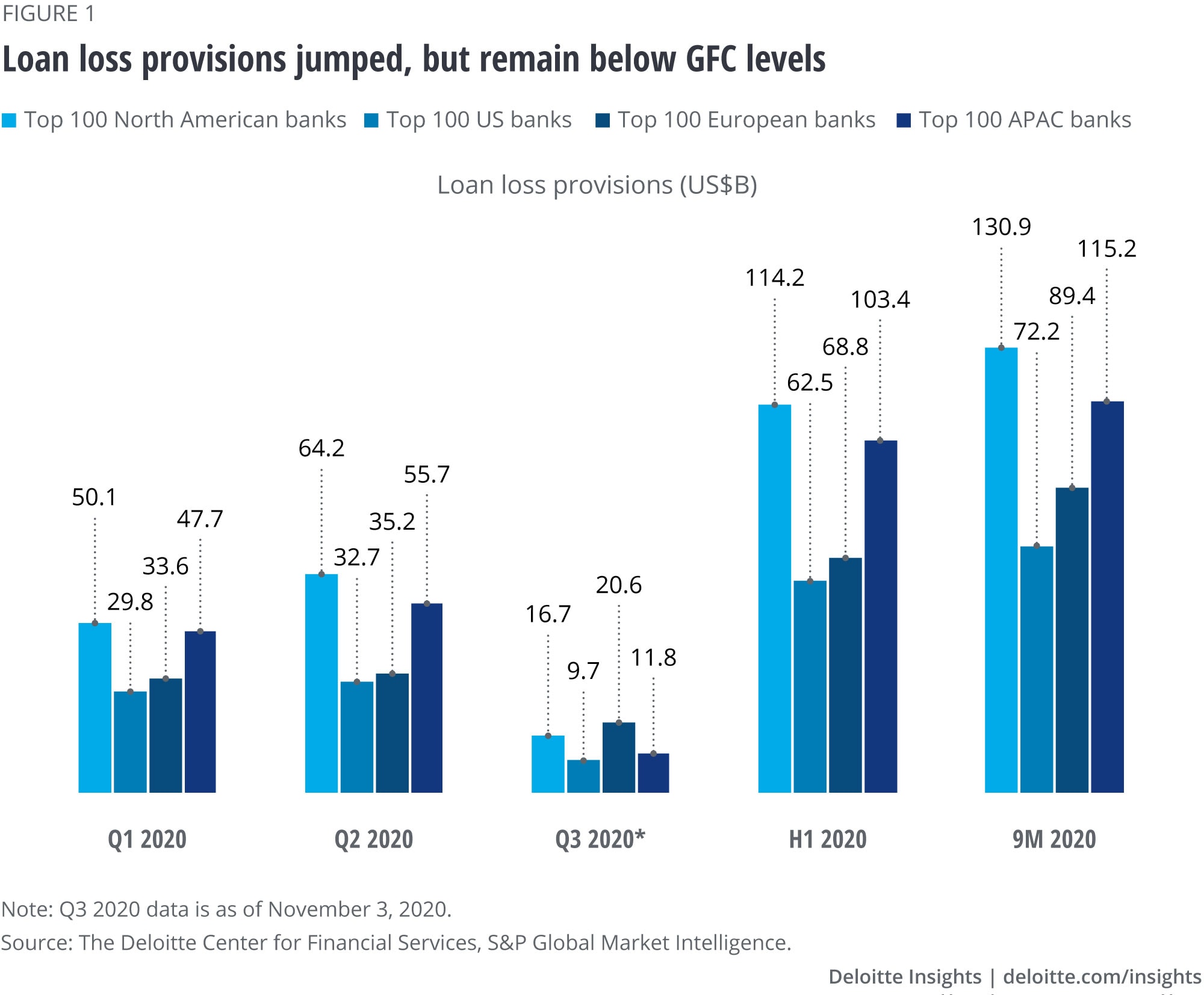

The Deloitte Center for Financial Services estimates that the US banking industry may have to provision for a total of US$318 billion in net loan losses from 2020 to 2022, representing 3.2% of loans.3 While losses can be expected in every loan category, they may be most acute within credit cards, commercial real estate, and small business loans. Generally, these losses are smaller than during the GFC, when US banks recorded a loss ratio of 6.6% from 2008 to 2010.4

As of Q2 2020, the top 100 US banks had provisioned US$103.4 billion, in contrast to US$62.5 billion for the top 100 European banks and US$68.8 billion for the top 100 banks in Asia-Pacific (figure 1).

Deloitte’s proprietary forecasts for the baseline economic scenario indicate that the average return on equity (ROE) in the US banking industry could decline to 5.6% in 2020 but then recover to 11.7% in 2022 (figure 2).

Similarly, sell-side broker estimates suggest that the average ROE of the top 100 banks in North America,5 Europe, and APAC could decline by almost 3 percentage points, to 6.8% in 2020. Banks in North America and Europe aren’t expected to recover to 2019 levels anytime soon, with APAC banks potentially only getting near their pre-COVID-19 ROE average level of 9.2% by 2022. Low rates are expected to keep net interest margins (NIMs) suppressed, creating strong headwinds to banks’ interest income growth.

Acceleration and deceleration of megatrends

One of the most notable effects of the pandemic is the scale and acceleration of several megatrends, and deceleration of others (figure 3). Until the pandemic hit, almost everyone believed certain societal forces were here to stay, such as the sharing economy, urbanization, and globalization. But remarkably, the pandemic seems to have slowed these global megatrends.

On the other hand, it is now abundantly clear that COVID-19 has acted as a catalyst for digitization. In addition to accelerating digital adoption, the crisis has also served as a litmus test for banks’ digital infrastructure. While institutions that made strategic investments in technology came out stronger, laggards may still be able to leapfrog competitors if they take swift action to accelerate tech modernization.

But to fully realize the digital promise in the front office, banks should use various levers to elevate customer engagement. These can include creating an optimal mix of digital and human interactions, using data intelligently, establishing novel partnerships, and deploying compelling service delivery models.

The net impact of these megatrends, combined with macroeconomic realities such as the low-interest rate environment in the decade ahead, should fundamentally reconfigure the banking industry. First and foremost, traditional revenue sources and business growth in established segments will likely be moderate at best, which would force banks to find new pathways to profitable growth. Second, scale, more than ever, could become critical as profitability pressure will put costs into greater focus. And third, advanced technology is expected to be at the heart of everything banks do.

The economic damage from the pandemic is self-evident. Unemployment rates around the world could remain at elevated levels for the foreseeable future. As a result, there could be a striking growth in global poverty, with as many as 150 million people pushed into “extreme poverty” by 2021.6 There are already signs of worsening income inequality and a growing number of women dropping out of the workforce.

Banking with a purpose

While banking seems to be changing, so does the purpose of banks. Societies around the world now expect banks to help address income inequality, racial and gender inequity, and climate change. As vital engines of growth in the global economy through a multitude of roles—financial market intermediaries, asset owners, investors, and employers—banks have a critical role to play in sustainable finance. In addition to helping allocate or redirect capital toward economic activities that are net positive to societies, they can also nudge new behaviors among clients and counterparties.

While some unique challenges remain—the lack of common global standards, insufficient data, and unclear metrics to assess sustainability performance and outcomes—these issues are starting to be addressed. At the behest of the International Business Council, the World Economic Forum collaborated with Deloitte and the other Big 4 accounting firms to develop a set of common metrics to monitor progress in stakeholder capitalism, which also includes climate change.7

Banks can play a leadership role in driving the sustainable finance agenda but will need to engage with other institutions to solve the many problems in this area.

Lessons from the pandemic

Forced to respond to some exacting realities, banks learned valuable lessons in the early months of the pandemic. There was no existing playbook, so bank leaders had to find new ways to do things. Traditional constructs and friction were dismantled in favor of clarity and agility. New levels of internal and external collaboration were achieved. Cultural norms and practices related to decision-making were discarded. Instead, employees were trusted to do the right thing and empowered to act.

Going forward, banks should look to institutionalize some of these learnings to create more agile workforces. They should develop new talent models to facilitate flexible, self-organizing teams that come together for a common purpose. Institutions should also focus on workplace redesign to help strike the right balance between in-person work environments and remote arrangements, which should be based on the specific needs of various roles or jobs. Of course, the goal of these changes should be to boost productivity, creativity, and collaboration.

Bold moves for an uncertain future

In this report, we offer perspectives on how these lessons can be applied to strengthen resilience and accelerate transformation in the following areas: digital customer engagement, talent, operations, technology, risk, finance, M&A, and sustainable finance.

In the short term, banks will need to confront ongoing challenges from the pandemic and boost their resilience—whether it is capital, technology, or talent.

For instance, maintaining resilience may pose a challenge if employee productivity declines from the myriad effects of the pandemic. Our survey of 200 global banking executives revealed that this challenge is particularly acute in Europe, where almost 60% of survey respondents indicated that employee fears of returning to work will hamper their ability to succeed after the pandemic. Interestingly, respondents in North America (35%) and Asia-Pacific (38%) were not as pessimistic. (For more information about our survey, see "Survey methodology.") Banking leaders might have to make difficult trade-offs between productivity and well-being.

More than one-half of respondents are reassessing their global footprint (countries, cities, office configurations) and preparing more comprehensive crisis management approaches and documentation (figure 4).

The banking industry will confront a range of challenges in 2021, many ongoing, but also some new obstacles. Uncertainty about the effects of the pandemic will likely remain for the foreseeable future. But this should not prevent bank leaders from reimagining the future and making bold bets. They should institutionalize the lessons from the pandemic and build a new playbook by strengthening resilience now and accelerating the transformation in the postpandemic world.

Sections

Sustainable finance: A unique opportunity for inspiring leadership

The world is beset with unprecedented challenges. The pandemic is perhaps the most formidable test right now, but income, racial, and gender inequities, along with persistent risks from climate change, are no less daunting. Banks have embraced their social purpose with a new energy and focus: how best to contribute to a more equitable and sustainable society.

As vital engines of growth in the global economy through their multitude of roles—financial market intermediaries, asset owners, investors, and employers—banks have a critical role to play in sustainable finance. Banks can help reallocate capital toward economic activities that are net positive to societies. They can also nudge new behaviors among clients and counterparties.

Many banks are embracing this growing power and influence and have been strengthening environmental, social, and governance (ESG) commitments in meaningful ways. Three-quarters of respondents said their institutions will increase investment in climate-related initiatives. Recently, for example, Goldman Sachs announced it will deploy US$750 billion across investing, financing, and advisory activities by 2030 on sustainable finance themes such as climate transition and inclusive growth.8 Similarly, UBS increased its core sustainable investments by more than 56%, to US$488 billion.9

Regulators around the world are quite focused on the systemic impact of climate risk on financial markets and stability. Many have proposed new frameworks with a broader set of expectations. In the United States, the Commodities Futures Trading Commission urged financial market participants to “move urgently and decisively to measure, understand, and address …[climate] risks.”10 Similarly, the European Central Bank now expects banks “to integrate climate and environmental risks in business strategy, governance, risk management and disclosure.”11

There are also new laws in the works, such as the Climate Change Financial Risk Act introduced in the US Senate in November 2019, which calls for the US Federal Reserve to help develop climate risk stress-test scenarios.12

Similarly, various industry entities, such as the Institute of International Finance, the World Economic Forum (WEF), the Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures, and the Partnership for Carbon Accounting Financials (PCAF) have also proposed structural changes to climate risk standards and transparency.13

While banks have made good progress on sustainable finance, there is much more that can be done.

Across industries, sustainability goals often lack transparency and connection to the day-to-day business activities, such as lending or underwriting. Greenwashing—relabeling and branding existing business activities as supporting a green agenda—is also an unpleasant reality. Varying and confusing terminology, and the lack of commonly accepted global standards are another barrier. Sustainability organizations are making efforts to address these issues. For instance, the PCAF has developed a global carbon accounting standard, while the Global Sustainability Standards Board is setting standards for reporting.14 But there still isn’t enough coordination and consensus across regions and within the financial services industry.Other persistent challenges are insufficient data and the use of imperfect metrics to assess sustainability activities, performance, and outcomes. Of course, this is a broader cross-industry problem that banks can work with clients and data vendors to address. Within banks, while the board and CEO set the tone and inspire action, the chief sustainability officer should be empowered to more forcefully influence culture and behaviors across the institution. The chief risk officer (CRO) is also central to this transformation. CROs must ensure that climate risks are integrated into their risk management frameworks and practices and more directly embedded into stress-testing exercises. Translating these goals into business-specific actions and outcomes will be a balancing act, and may require some short-term financial sacrifices.

Last, banks should also bolster their transition risk services and solutions to clients as they decarbonize.15 The field is ripe for capital market innovations to create and trade carbon credits, and, more broadly, share climate risk across market participants.

Some of these challenges also translate to the social sphere. COVID-19 has exacerbated income inequality and gender and racial disparities. Some banks have already demonstrated leadership in multiple ways, but most crucially, through financial commitments. For instance, JP Morgan committed US$30 billion to fight the racial wealth gap.16

Sustainable finance is not just about doing the right thing—it can also be good business. Take financial inclusion, for example. Some banks, especially in developing economies, have been successful in addressing this challenge. Likewise, many fintechs and nonbanks have designed innovative solutions. Banks should heed this call and get more creative about building economically attractive and durable business models. These efforts should also be extended to other societal challenges, such as financial education, health care access, and affordable housing. Banks cannot solve many of these intractable problems on their own. It will likely take collaboration across industries and government agencies to move the needle in a meaningful way. Banks should take a leadership role, and continue to engage with regulators, industry organizations, clients, and counterparties to build a robust, pervasive, and persistent sustainable finance agenda going forward. They may discover that such actions may also yield commercial benefits.

Sections

Digital customer engagement: The next frontier

The promise of digital banking was never fully realized, largely due to customer reluctance and/or a lack of attractive digital solutions. But the pandemic turbocharged digital adoption across products and demographic segments. For instance, 44% of retail banking customers said they are using their primary bank’s mobile app more often.17 Likewise, at Nubank, a Brazilian digital bank, the number of accounts rose by 50%, going up to a total of 30 million.18

There is a similar pattern in commercial banking as well. Bank of America’s business banking app witnessed a 117% growth in mobile check deposits.19 Similarly, digital roadshows became the norm in marketing securities.

What is even more impressive is the spike in digital sales—the holy grail in digital banking. For instance, at Standard Chartered, retail banking digital sales grew 50% year-on-year in H1 2020.20

But to what degree will this increased digital adoption persist beyond the pandemic? Of course, banks would benefit if most of their customers transitioned to digital-only, self-service interfaces, which could result in significant cost savings.

However, evidence suggests that increased digital engagement does not necessarily translate into increased satisfaction. In the United States, overall customer satisfaction with retail banks tends to decline as customers transition away from branches to digital-only banking relationships.21 Similarly, in Canada, while mobile banking usage has gone up, customer satisfaction with mobile offerings has declined.22 In Australia, too, satisfaction with problem resolution declined as interactions moved from in-person to digital.23

And while only a few customers may be planning to switch institutions now, customer retention risk could resurface once the pandemic is over, particularly with younger customers.24

Therefore, despite the higher rates of digital customer engagement, keeping customers satisfied, retaining them for the long haul, and gaining a greater share of wallet may still be as daunting as ever.

So, what should banks do?

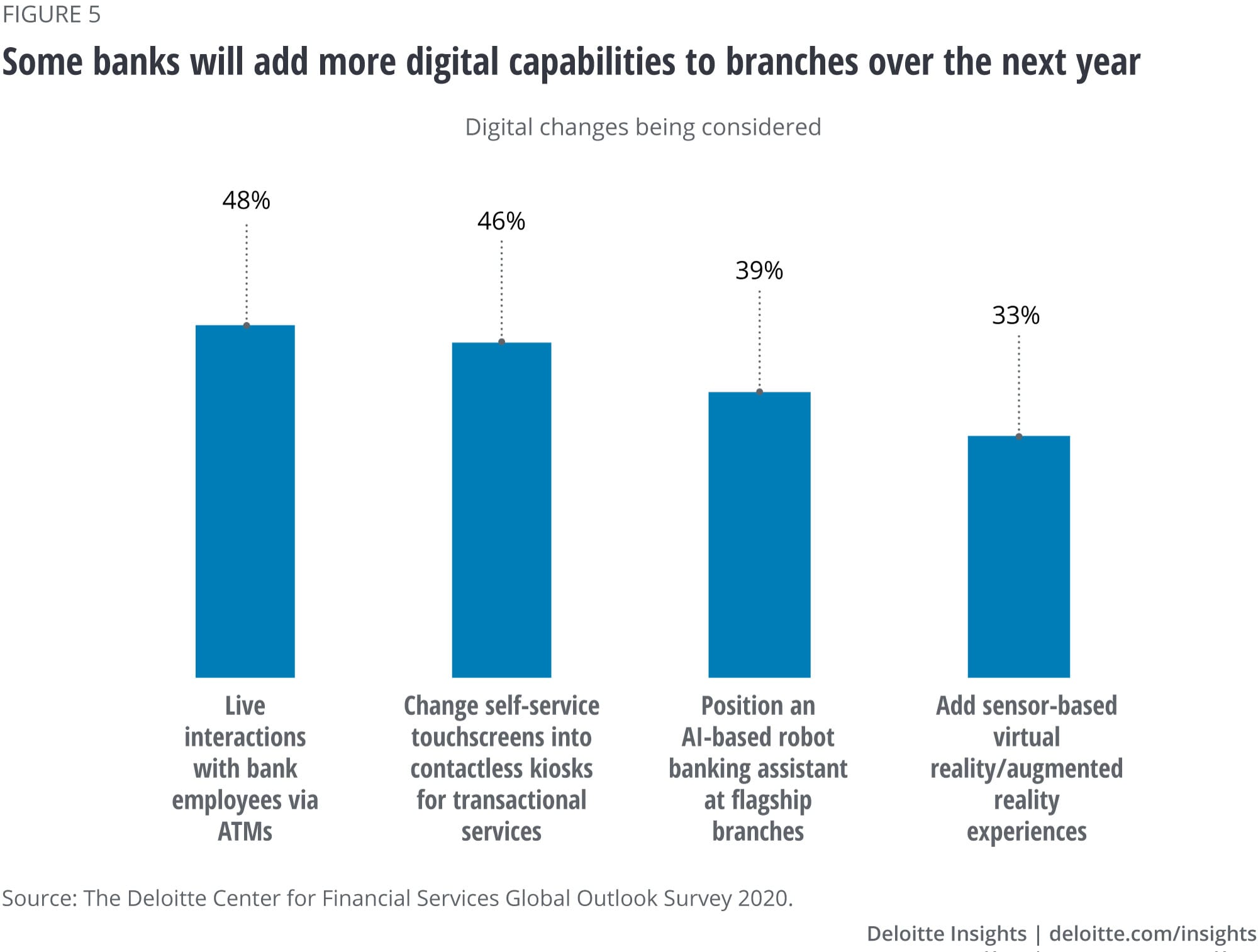

First, they should prioritize retaining first-time users of digital channels by using targeted offers and engagement strategies. At the same time, banks should continue to invest in digital, customer-facing technology to provide the seamless experience the industry has been seeking for a while. These enhancements may not only cover digital-only channels but also in-branch experiences, such as self-service digital kiosks/interfaces. Nearly one-half of respondents indicate their institutions are considering live interactions with bank staff via ATMs, and installing self-service, contactless touchscreens (figure 5). In addition, banks could incorporate artificial intelligence (AI)-based banking assistants and sensor-based augmented reality and virtual reality experiences.

Also, hyperpersonalized services that can factor in a customer’s financial well-being holistically should form the core of customer relationships. To achieve this goal, banks can integrate their disparate data architecture across lines of business (LoBs) and functions and combine it with AI-driven analysis to create a 360-degree view of customers. BBVA, for example, built new data analytical capabilities through a global data platform and a dedicated “AI factory.”25

Another lesson banks could learn from fintechs is how to leverage customer data and analytics to digitally deliver hyperpersonalized services and engage customers—together with partners—in new and differentiated ways. 26

The pandemic has already resulted in significant increases in forbearance and collections. Because of banks’ limited capacity to serve these customers, chatbots and conversational AI tools are being implemented. Improving the digital experience by adding these tools could help banks engage with these customers and answer their questions.

In these and other customer interactions, banks should be sure to maintain the human touch. Digital interfaces are essential, and desired, but customers tend to need person-to-person experiences to boost loyalty. For instance, educating consumers on better debt management and being empathetic in debt collection efforts could help strengthen banks’ customer relationships and engender trust.

In both retail and institutional contexts, novel banking platforms to engage customers across the full range of their financial (and possibly nonfinancial) needs could be compelling differentiators and offer new pathways to profitability. DBS Bank’s Marketplace allows customers to conduct property and vehicle transactions, book travel, and compare and switch utility plans. It could be a precursor to what one might see more broadly in the future.27

To fully realize the digital promise in the front office, banks should elevate customer engagement by deploying an optimal mix of digital and human interactions, intelligent use of data, novel partnerships, and compelling service delivery models.

Sections

Talent: Boosting well-being and productivity through resilient leadership

Banking leaders around the world have faced an array of challenges on the talent front, from shifting to a remote, distributed workforce to finding ways to keep employees engaged and productivity high.

Additionally, many banks took or are planning to take several workforce-related actions (figure 6), such as offering flexible schedules to employees. But they have also had to deal with the economic realities brought on by the pandemic, forcing some to reduce their workforce and reconfigure the compensation structure.

Even before the pandemic, the future of work was top of mind for many banking executives. It is hard to say what the exact implications of COVID-19 will be on how work might evolve. But these changes, along with other forces, such as digital acceleration, will likely transform talent models in the banking industry.

Sustaining resilience and accelerating transformation of the talent function

Looking ahead, as banks adapt to the economic realities of 2021, bank leaders will likely need to make some hard decisions on optimal talent models. They must also move beyond current concerns about well-being and productivity to enhance learning, teaming, and leadership. Using the right technology and tools will be critical to the success of these programs.

The pandemic drew attention to well-being like never before: Most executives surveyed (80%) said their company was increasing focus on safety and well-being. Citigroup, for example, is training its managers to care for employees’ physical and emotional well-being, whether they work from home or in the office.28

As the pandemic continues and uncertainties remain, bank leaders should continue to proactively recognize employee concerns, be sensitive to their personal/family needs, and prioritize physical and psychological health efforts that can also help maintain employee productivity. In remote environments, however, managing can be a tricky dance: Team leaders will need to try to strike the right balance between maintaining their teams’ motivation and productivity levels without micromanaging.

Team leaders should also focus on ensuring that employees feel a sense of belonging at work. They should be afforded opportunities to learn how their work fits into the bigger picture, to gain a deeper appreciation for how they are making an impact within and outside the organization.29

Banks may also need to transform their talent strategies to enable employees to learn better, faster, and more frequently. Programs that focus on “learning how to learn,” curated learning, and learning via experiences should lead to better retention and more positive organizational results overall.30 Success in the post-COVID-19 world will likely demand a new set of skills, but simply reskilling the workforce is not expected to be enough.

Establishing new talent models should facilitate flexible, self-organizing teams that come together for a common purpose. Workplace redesign should also be a key focus as institutions strike the right balance between the workplace and virtual/remote arrangements, based on the specific needs of various roles/jobs. Boosting productivity, creativity, and collaboration should be the ultimate goals.

The nature of teaming will likely also need to change. COVID-19 has revealed that many banks still have outdated organizational structures and hierarchies. New team structures should be tied directly to how work gets done.

Technology, meanwhile, is already being used to improve talent outcomes and promote resilience. It should also play a fundamental role in improving productivity in a virtual environment, boosting learning, creating flexible teams, sharing knowledge, making information flows efficient, and promoting new forms of collaboration across the organization. Leaders must recognize that technology deployment in remote settings can be a two-sided coin: videoconferencing fatigue on one side, the need for social contact on the other.

While uncertainty around large-scale vaccine availability persists, over the next few months, talent functions will be busy crafting safe return-to-workplace strategies. The most successful banks will likely be those that can quickly adapt and make changes to their workforce and reconfigure their workplaces.

For instance, banks’ IT departments have used agile practices successfully for software development and testing. But agile methods should now be integrated into business operations. This integration is at the heart of the future of work. While cultural and other factors may make it more challenging, implementing these changes can result in material outcomes. New tools and technologies can certainly help. It has to be seen as a continuous process improvement, leading to competitive differentiation.

Finally, banks’ future talent strategies should be agile and adaptable. Developing new talent models is expected to require innovative and inclusive leadership focused on resilience. To be most effective, these resilient leaders31 should be future-focused and empathetic.

Sections

Operations: Building long-term resilience and using technology for strategic cost transformation

COVID-19 inflicted enormous stress on banks’ operations, and there were hiccups at some institutions. But many banks handled the challenges well. Overall, the relatively smooth transition to a new virtual operating model is a testament to years of preparation and regulators’ attention on operational resilience.32

The pandemic also highlighted the need for greater rigor in some banks’ business continuity planning, crisis management, and recovery.33 Moreover, it exposed vulnerabilities in their global footprint and dependence on external provider networks; in countries observing national lockdowns, many institutions experienced a disruption in offshore delivery centers.

Strengthening resilience and accelerating transformation in operations

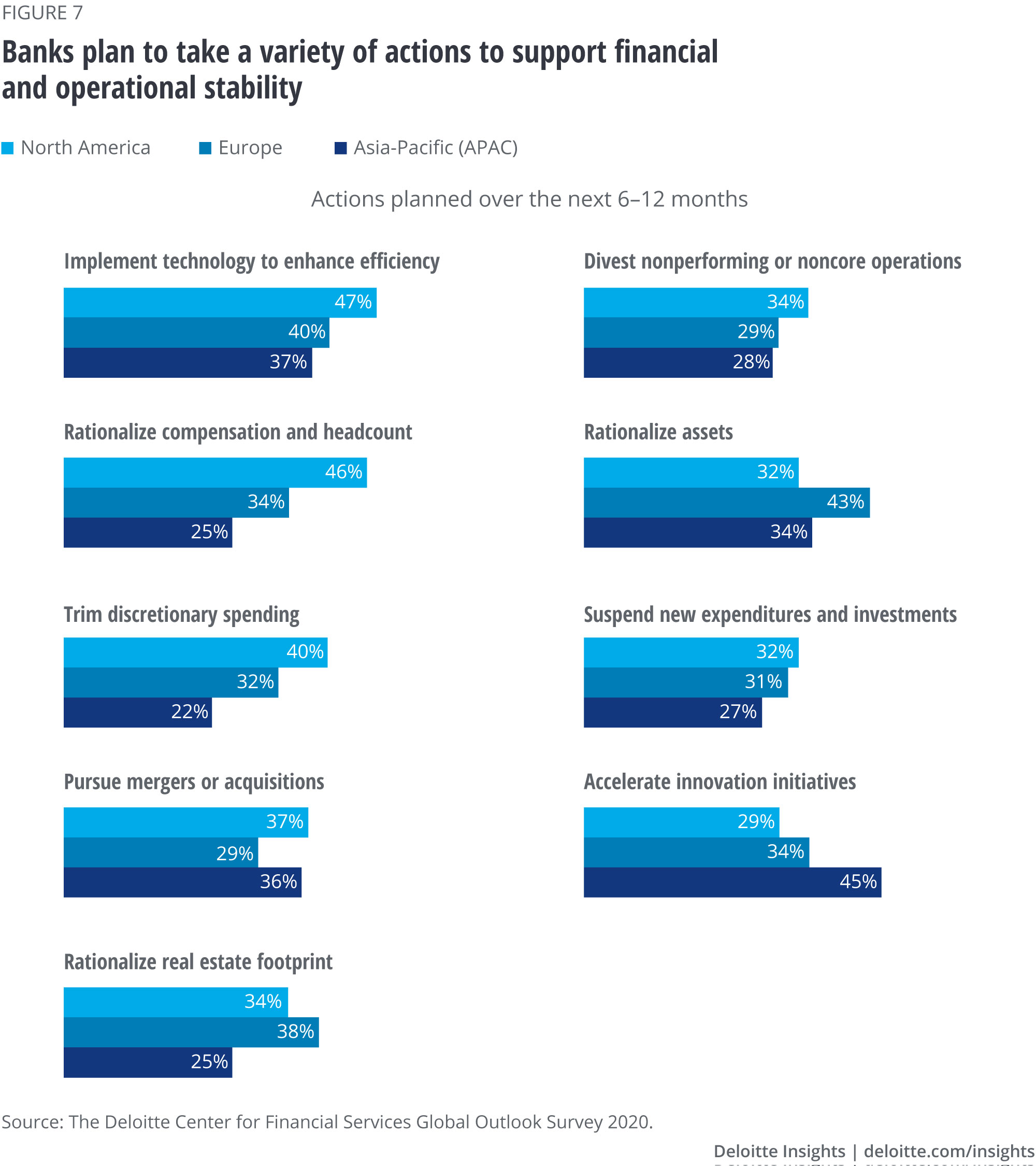

Going forward, strengthening operational resilience will likely be a main challenge many banks face.34 While there’s no silver bullet, banks could reassess their global footprint and dependence on third parties, conduct more frequent simulation exercises, and improve information systems to respond quickly to future events. For instance, they may consider nearshoring some offshore positions to embrace a true multilocation model. This may build in some redundancy, but it would help reduce operational risks. In our survey, a majority of respondents reported implementing or planning to implement some of these resilience measures (figure 7).

Undoubtedly, agility goes hand in hand with resilience. Banks should eschew perfection in favor of agile execution. Leaders should empower their front-line workforces with more decision-making authority by creating flatter team structures and revisiting responsibilities and accountability.35

Many banks could also pursue a structural cost transformation initiative to bolster operational efficiency (figure 7). They can use branch and office space rationalization as one of the levers to lower fixed costs. However, traditional branch closures could be partially offset by drive-throughs and next-gen branches that enhance customer experience. For instance, US Bancorp plans to maintain its café-style branches and reemphasize its role in facilitating conversations with customers as transactions increasingly shift to digital channels.36

Some banks could also be conducting layoffs to rationalize costs. One-third of respondents indicated their firms are planning to do so. So far, most bank leaders seem less receptive to employing alternative workforce models—less than one-third of respondents mentioned their firms have transitioned to need-based, or "gig," workers. But exploring solutions to maintain productivity levels in a remote work environment will be crucial.

Concurrently, banks should continue to explore how technologies, such as cloud, machine learning, robotic process automation, and distributed ledger technology, can simultaneously contribute to significant cost savings, while also helping increase speed, improve accuracy, and provide scalability. Streamlining front-to-back data flows and deploying data analytics will remain prerequisites to achieve the desired efficiencies.

Needing to make these investments in a low interest rate environment, some banks, especially smaller ones, may pursue mergers and acquisitions (M&A) opportunities for scale. Among respondents from smaller banks (annual revenues between US$1 billion and US$5 billion), 57% said their institutions could pursue M&A opportunities over the next 6–12 months. Meanwhile, one-third of respondents indicated their banks may also look at rationalizing assets or divesting noncore operations.

In addition to these enterprisewide initiatives, implementing LoB–level cost transformation efforts may be required. LoB leaders should be empowered to determine where their energy and resources should be focused. They should be able to change the way work gets done by introducing self-service options, streamlining data flows and operations with automation, and restructuring for optimal service delivery. LoB heads should also be asked to assess whether they are competitive in all the spaces they play, and if not, consider exiting those businesses and activities.

Chief operating officers may also need to challenge cost management orthodoxies, such as outsourcing noncore activities or using technology to do traditional manual tasks. This would likely require a top-down cultural change.

Sections

Technology: Capitalizing on the multiplicative value of different technologies

Banks were making rapid strides in their digital transformation journey, but the pandemic accelerated the pace. To meet the demands of the new realities, projects that once took months or even years were accomplished in just weeks, such as the banks' response to the US Paycheck Protection Program (PPP). Banks that invested in digitizing their businesses over the last decade demonstrated higher agility and resilience in adapting to COVID-19-led changes than others.37

However, the first half of 2020 exposed vulnerabilities in banks’ technology arsenals. Nearly four in five respondents agreed38 that COVID-19 has uncovered shortcomings in their institution’s digital capabilities. Technical debt in the form of legacy infrastructure and data fragmentation across the enterprise continues to impede banks’ digital transformation initiatives.39 But in many institutions, digital inertia has faded: There is now more appetite for technology-driven transformation, especially in core systems.

Strengthening resilience and accelerating transformation in technology

In the near term, bank technology departments should bolster their technology infrastructures to offset stresses in the market today. For instance, as banks face capacity constraints in workouts and loan restructuring, conversational AI systems could provide personalized customer experience and improve call-center efficiency.40

Looking ahead, bank technology leaders should place bold bets on initiatives that could transform businesses, such as core systems modernization. There may not be one core systems solution that fits all, so to determine which option is best, banks should evaluate the sustainability of current platforms, their appetite for risk, and the need to innovate their offerings.

Meanwhile, new approaches may be needed, such as modular execution and experimentation on the edge, to achieve the full benefits of this modernization. Creating stronger incentives to decommission legacy systems could help in this effort. Also, technology leaders should factor in how the current technology stack can interface with not just next-gen but next-next-gen innovations, such as advanced machine learning techniques, blockchain applications, or quantum computing.

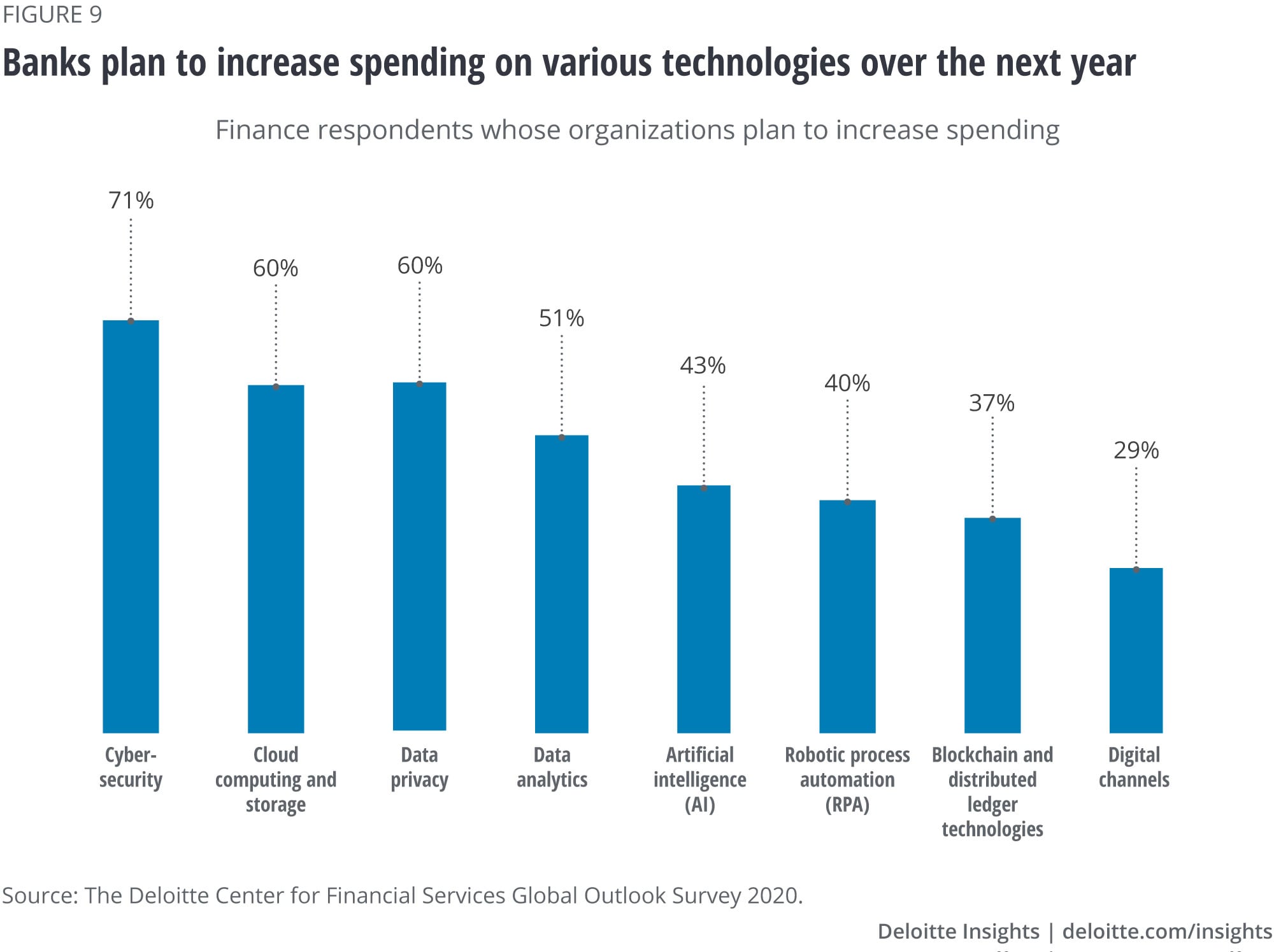

Until now, cloud migration efforts were predominantly focused on cost reduction, modernizing the technology stack, and more recently, virtualizing the workforce. But the real promise of cloud may lie in enabling banks to reimagine business models, foster agility, achieve scale, drive innovation, and transform customer experience. Moreover, transitioning to cloud-native, API-driven core systems could help bank leaders radically rethink product design, as neobanks and bigtechs have done. Indeed, our respondents indicate spending on cloud will increase over the next year. This is especially true for respondents in North America, at 56%, and Asia-Pacific, at 61%.

While AI adoption is still not as widespread,41 and the full potential has yet to be realized, banks must recognize that AI does not exist in isolation. Almost 42% of respondents anticipate increased investment in AI technologies at their firms over the next year. AI should be embedded/combined with other technologies, such as cloud, IoT, 5G, and distributed ledger, to create multiplicative value. No matter the application, ethical use of AI should remain a given.

Progress on digital transformation could fall short if banks do not get a handle on data quality, architecture, and governance. New solutions, such as knowledge graphs, are available to extract the full value of data by addressing data fragmentation.

Additionally, the technology function should play a critical role in banks’ structural cost transformation efforts. First, this can help ensure technologies are used deliberately to change cost structures. Second, to cut costs, banks should reexamine the build-buy-outsource/offshore model for technology projects. One-half of respondents said their institutions’ inclination to outsource has somewhat or significantly increased during the pandemic, while about 40% indicated a decline in their institution’s intent to build or buy (figure 8). Increasingly, banks can deploy managed services to cut costs for critical but less-differentiating activities.

Lastly, chief technology officers, along with other C-suite executives, should ask how far, how deep, and how wide digital transformation should go to help banks achieve their long-term goals. Deciding how much change is needed, and what the role of technology is in this transformation, are important strategic questions to address.

Sections

Finance: Driving strategic value through data

When the pandemic brought the world to a halt, bank chief financial officers (CFOs) and treasurers faced a barrage of priorities. The robust capital levels banks had built up over the past decade reduced near-term stress, and deposit inflows and government support of capital markets minimized liquidity concerns. In the initial phase of the pandemic, banks tightened lending standards. Most banks also responded well to regulatory reporting requirements, providing timely and high-quality data.

More recently, CFOs have been leading cost transformation efforts, which should remain a key priority for banks in the years ahead.

Strengthening resilience and accelerating transformation in finance

Until the current economic disruption subsides, CFOs and treasurers should continue to focus on preserving liquidity and boosting capital. Unfortunately, though, banks could be hard-pressed to put this cash to work due to ample deposits and limited options for attractive yields.42

But these efforts cannot happen without establishing more robust and accurate planning and forecasting,43 which may include modeling the pandemic’s impacts on markets, customers, and counterparties to construct a broader view of potential impacts and actionable insights.44 Pushing financial planning and analysis processes into business units should improve granularity and accuracy.45 However, using current legacy infrastructure in these endeavors may be challenging for many banks.

Cloud applications can help in this regard, enabling continuous planning with rolling and driver-based forecasting. Together with AI, these solutions could also improve resilience by boosting cashflow forecast accuracy.

The finance function should also take on a more strategic role by actively establishing a two-way information exchange, empowering business units with real-time business insights46 and smarter scenario-planning tools.47

CFOs may also need to rethink their operating models in light of the new distributed work environments. They should consider offering “finance-as-a-service” to internal stakeholders, which would enable more robust business decisions.

AI could also be deployed to automate finance processes and free up capacity to take on more strategic activities.

Finance leaders already acknowledge the need for some of these changes. More than 60% of respondents in the finance function expect to increase cloud investments, and 51% said their firms will increase spending on data analytics (figure 9). But only 40% and 43% expect increases in investment spend on automation and AI, respectively.

CFOs should be flag bearers of an innovative, data-driven decisioning framework and more targeted capital allocation,48 which can yield higher-quality outcomes, such as better return on investments.

Moreover, as the finance function becomes more analytics-driven, new skills will likely be required in data science and coding. To attract this talent, banks could need to offer agile work environments and new technologies that would shift away from having employees handle repetitive and mundane manual tasks, allowing them to focus on analytical, creative, and strategic activities.

Last, the finance organization should help manage climate risk. Ultimately, the impacts of climate risk are not just social or reputational, but financial as well.

Sections

Risk: Creating a new risk control architecture

The COVID-19 pandemic dramatically altered the risk landscape for the banking industry on a number of fronts. Initial spikes in asset price volatility significantly increased market risk, testing banks’ financial stability and risk resilience. The virtual work arrangements many banks adopted introduced new operational risks. The new parameters brought existing risks, such as business continuity planning and conduct risk, into greater focus.

Furthermore, it soon became clear that banks could be facing sizable credit losses across their loan portfolios. But credit loss models were not calibrated to accommodate extreme, out-of-bounds macroeconomic conditions, raising doubts about the model outputs. Credit losses will likely increase as the economic recovery stalls.

Meanwhile, regulator concerns about financial crimes in the areas of cyber fraud and anti-money laundering increased. Regulators were also keen to receive more detailed and frequent reporting from banks on the various risks they were facing.

However, with crisis comes opportunity, even during these challenging and uncertain times. Considering this ever-evolving risk landscape, banking risk leaders should reboot their risk frameworks to ensure long-term resilience.

Strengthening resilience and accelerating transformation in the risk management function

To start, maintaining focus on operational risks is critical. Conduct risk, for instance, remains a potent threat. While reported incidents of conduct risk are not yet widespread, 72% of respondents said their institution was looking into programs that reduce conduct risk. So, actively monitoring and exerting a strong risk control culture, possibly through new surveillance and control tools, should be a priority.

Banks should also buttress risk sensing. But achieving sound data integrity across the risk control framework still seems easier said than done. There are too many manual processes involved across the risk management function.

In addition to data quality and governance, another challenge is the prevalence of deficiencies in risk control design and architecture. Controls with poor supervision, self-assurance, and validation, with unclear responsibilities between the first and second lines, still remain. Here, leaders should take steps to enable the first line to take greater ownership.

In this regard, technology’s true power—its ability to reshape risk frameworks in more meaningful ways—has yet to fully be realized.

Banks’ risk programs and practices should also incorporate climate risk, which includes transitioning to a carbon-neutral society. Credit risk models may also need to be updated to factor in the effects of climate change on individual credits. These new assumptions and risk assessments should be more directly embedded into stress-testing exercises. The chief risk officer may also want to partner with the institution's chief sustainability officer, and industry organizations to create new risk standards and models that include climate risk.

Finally, in the post-COVID-19 world, risk fundamentals are unlikely to change, but risk leaders should rethink old governance models and the way they are applied. They should prioritize a risk management approach that is holistic, all-encompassing, and embedded across the business to ensure a resilient foundation in the long term.

Sections

Cyber risk: Investing for greater resilience

Cybersecurity remains a persistent challenge for the banking industry. Although much progress has been made, the threat volume, velocity, and variability continue to accelerate, as the attack surface expands through rapid digitization and externalization of digital infrastructure. And of course, the pandemic has tested the cyber resilience of banks, as the virtual/distributed work model became the norm. Insider risk is also increasing because of the psychological stress employees are likely to face as the pandemic continues.49

At the same time, the uncertain macroeconomic picture puts the focus on maintaining/enhancing cyber defense capabilities at stable or lower budgets, forcing more intense prioritization. Shortage of skilled talent in the cyber risk area often remains another obstacle, especially for smaller institutions.

Strengthening resilience and accelerating transformation

In strengthening cyber resilience, banks should both adopt more effective preventative controls as well as prepare for rapid recovery from adverse events caused by malware, ransomware, and other pernicious attacks. Additionally, to get ahead of emerging problems, banks should take a security-by-design approach, weaving cybersecurity requirements into all aspects of their digital architecture.

More specifically, in a recent Deloitte-FS-ISAC benchmarking survey,50 access control, data security, and detection processes were highlighted as the top investment priorities for financial institutions.

Ensuring only authorized users have access, assigning different privileges, and protecting customers from fraud, identity theft, and privacy abuses, while providing a seamless experience, is easier said than done. In this regard, robust identity governance and administration and next-generation authentication through password-less experience are considered effective solutions.

Enhancing data security and designing effective privacy management programs through a combination of programmatic and technology capabilities are also top priorities, according to the survey. Increased regulatory scrutiny on security and privacy, and migration to the cloud are amplifying this challenge.

Although detection processes and first-line responses have become quite sophisticated, there is room for further efficiencies through automation. This can enable shifting of resources to the more difficult threats. User behavior analytics and machine learning can further help detect potential anomalous behavior on the network and individual endpoints.

Sections

M&A: Rewriting the playbook for a postpandemic world

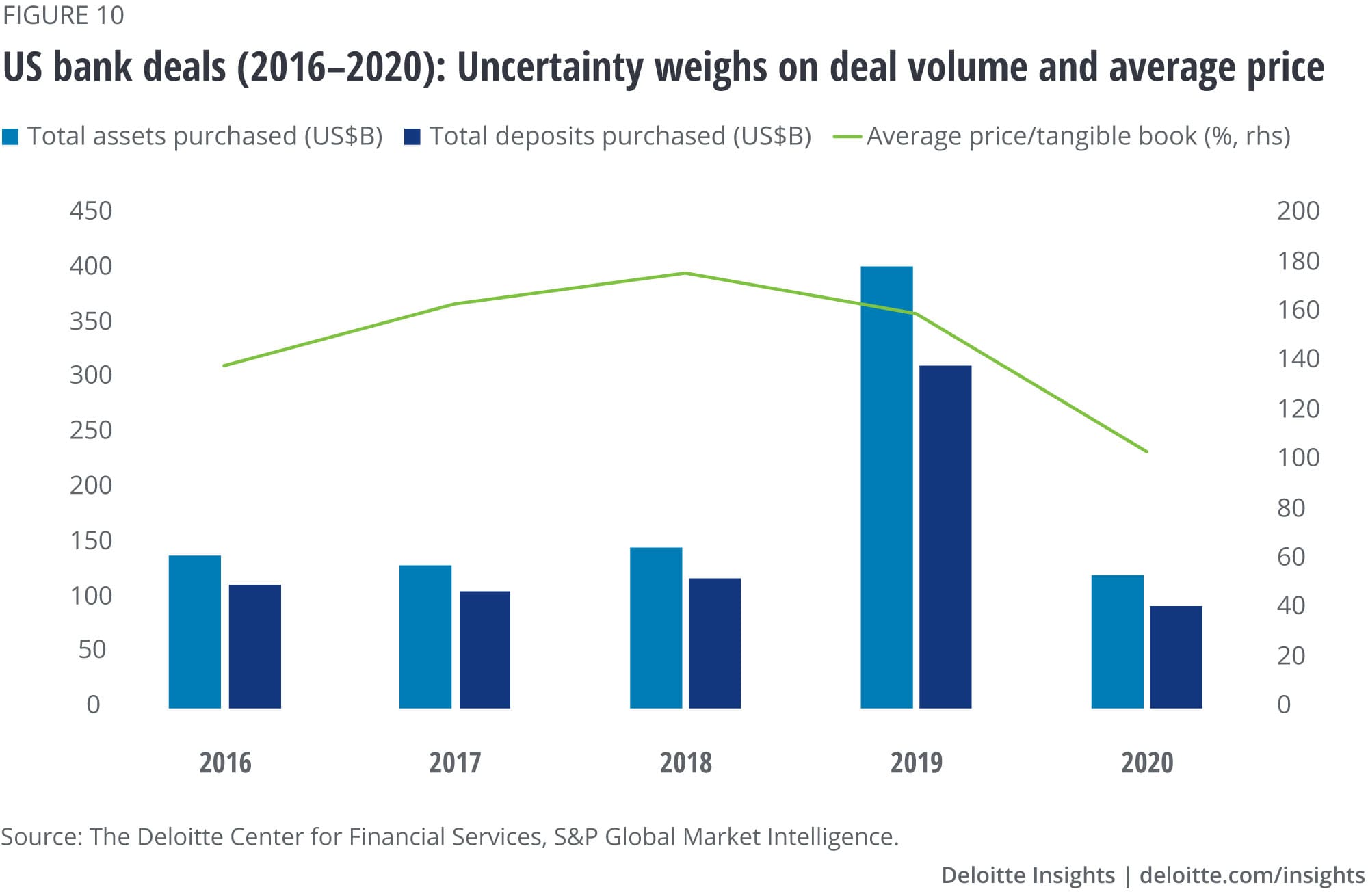

The pandemic brought M&A activity in the banking industry to a halt in the second of quarter of 2020. But since then, there has been a revival (figure 10). And despite the global uncertainty, M&A should move up on the bank executives’ agendas.

The basic rationale for M&A may remain the same as in recent years, but pandemic economics have altered the catalysts and inhibitors.

The most obvious is that banks, globally, need to counter the strong headwinds to achieve profitability, given compressed NIM from lower rates and lower demand for loans. Deloitte forecasts indicate that in the United States, both revenues and net income for US commercial banks won’t bounce back to reach prepandemic levels until 2022.51

In Europe, similar challenges exist, and overcapacity, fragmentation, and the lack of a banking union, could further confound recovery prospects.

To bolster revenues, many banks try to leverage fee income as the primary driver of growth, but such prospects may be limited, given the somber macroeconomic climate and surge in industry competition. Scale could become an even more dominant consideration: Banks will likely need economies of scale to survive, rationalize costs, and thrive. For instance, CaixaBank and Bankia, two Spanish banks active in a highly fragmented banking market, agreed to merge, forming Spain’s largest domestic retail bank.52 We could expect this dynamic to play out in other banking markets globally. Inorganic growth through M&A may seem like the only option, in some cases.

More than ever, modernizing the digital core and closing the gap in legacy infrastructure could feature prominently in the banks’ M&A calculus, as banks reposition themselves in the postpandemic world.53 On the supply side, M&A may be driven by banks considering sales of businesses to support earnings and rationalize their business models.

M&A activity in the fintech/digital lending space should also ramp up because fintechs will increasingly want to expand internationally and seek access to a banking license. And while digital lenders may want to diversify their funding sources, banks may look to acquire fintechs for their digital capabilities and to target new segments.

Lastly, M&A demand may also be spurred by private equity investors, who will want to deploy their growing dry powder, now that valuation levels have come back.

M&A activity may, however, be hindered by lingering uncertainty in assessing the true nature of credit risk in banks’ portfolios. This may also result in bid-ask spreads becoming too wide, which could worsen if there is further economic deterioration.

Other factors, such as political and regulatory uncertainty and changes to tax regimes, may loom large. For instance, regulators in Europe have reiterated the need for banks to consolidate across borders and drive diversification.54

Similarly, the US Department of Justice is contemplating an overhaul of its outdated bank merger competitive review guidelines to reflect the current realities of a digitized world.55 This may remove barriers to mergers and acquisitions, particularly among smaller/rural banks, according to the Conference of State Bank Supervisors.56

Strengthening resilience and accelerating transformation

As the pandemic remains a key challenge in the short term, it may be tempting to wait until after the dust settles to make any M&A moves, but deferring action could leave slimmer pickings. The adage that fortune favors the brave may be quite apt in the current context.

Caution should be exercised, and due diligence efforts may need to be modified to account for COVID-19’s unique impact on asset quality and industry competition. This expanded discipline should also include the role of new standards such as CECL. Banks may need a new set of tools, expertise, and processes to create a new M&A playbook that will withstand the postpandemic realities. Banking industry consolidation could kick into high gear.

Sections

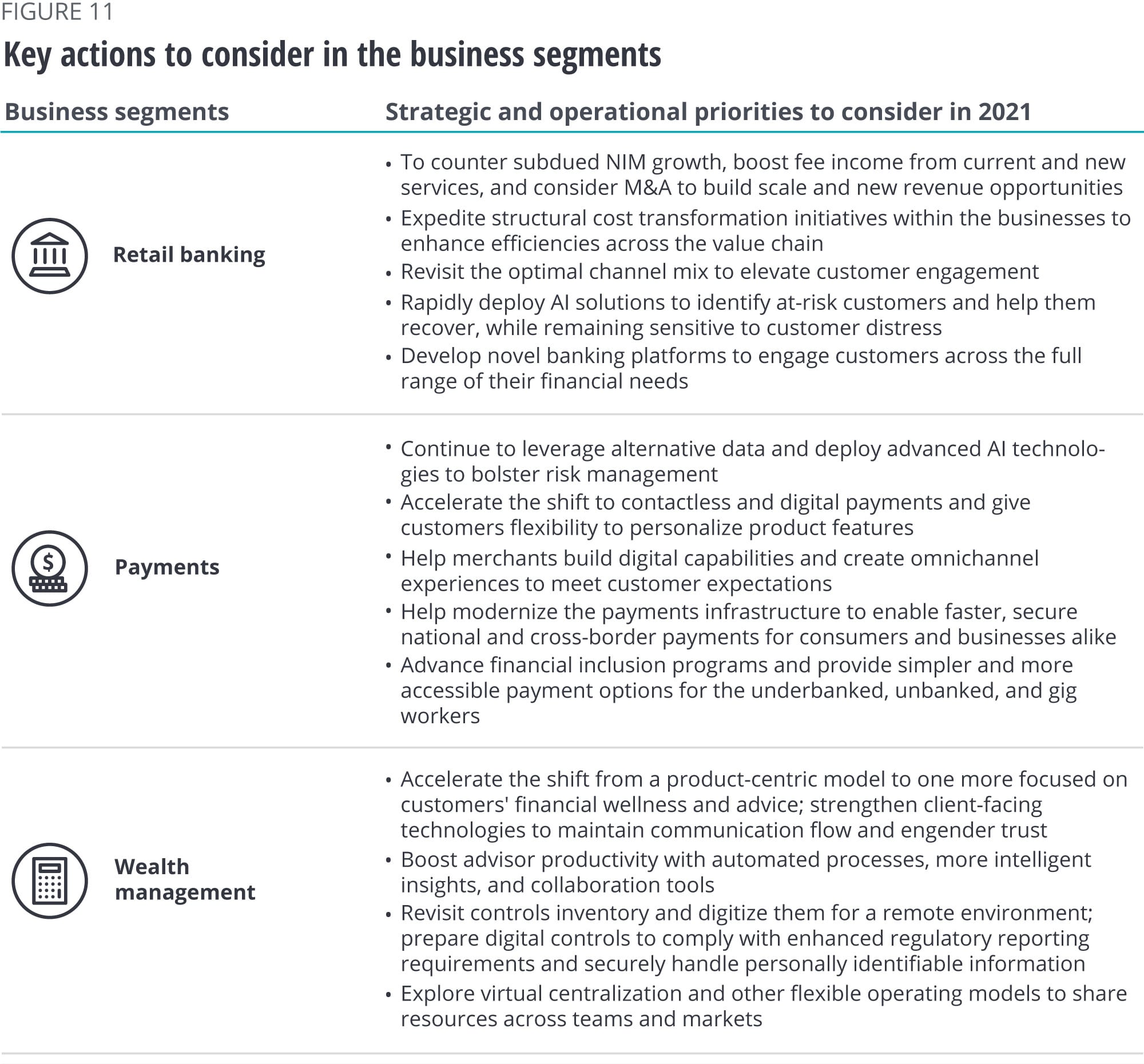

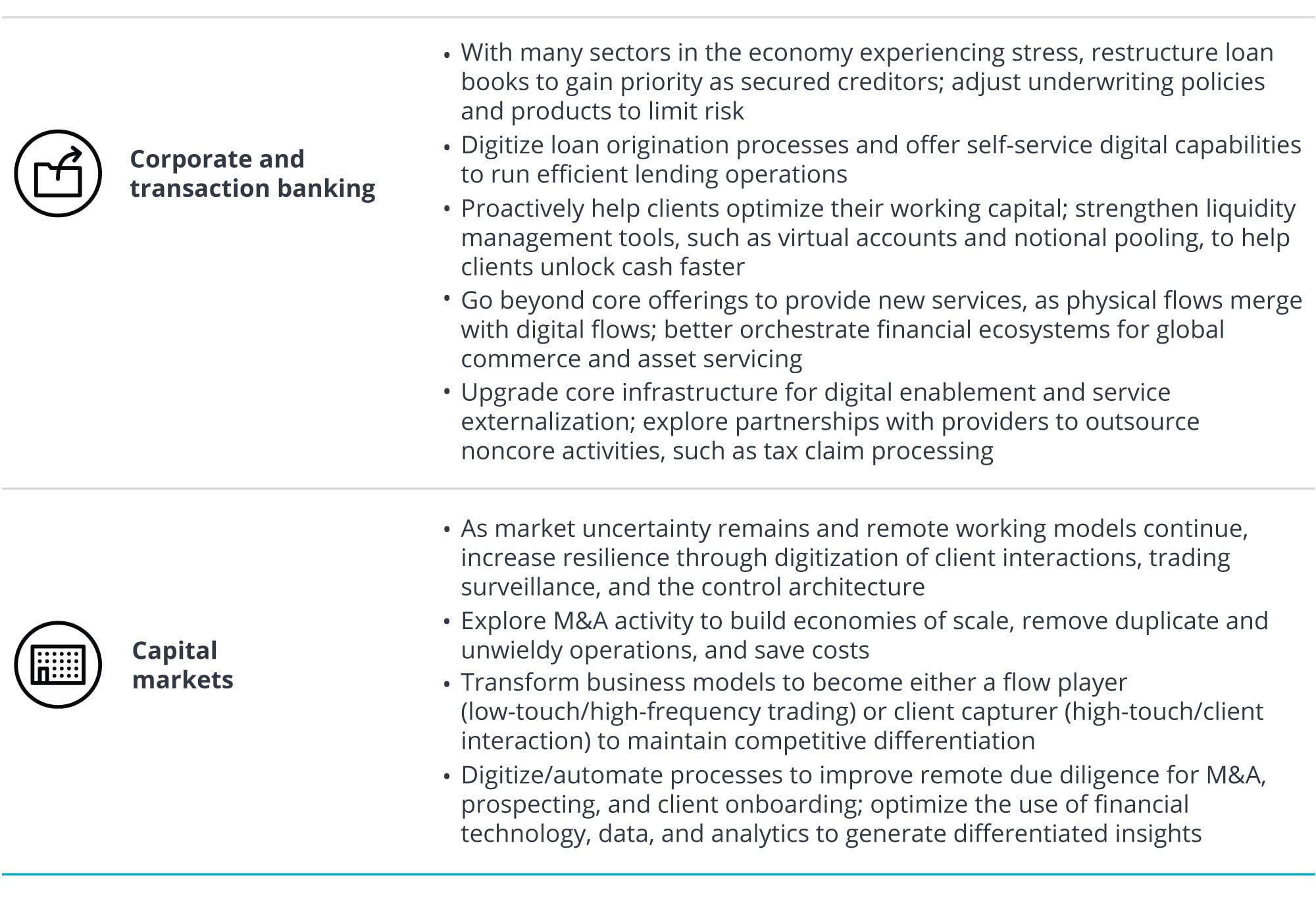

Key actions to consider in the business segments

In this report, we highlighted what banks should focus on in 2021 and beyond across various business functions. But how do these considerations translate to the individual business segments? In the table below, we highlight some key strategic and operational priorities for businesses to consider.

Sections

Survey methodology

The Deloitte US Center for Financial Services conducted a global survey among 200 senior banking and capital markets executives in finance, operations, talent, and technology.

Survey respondents were asked to share their opinions on how their organizations have adapted to the varied impacts of the pandemic on their workforce, operations, technology, and culture. We also asked about their investment priorities and anticipated structural changes in the year ahead, as they pivot from recovery to the future.

Respondents were equally distributed among three regions—North America (the United States and Canada), Europe (the United Kingdom, France, Germany, and Switzerland), and Asia-Pacific (Australia, China, Hong Kong SAR, and Japan).

The survey included banking and capital markets companies with revenues of at least US$1 billion in 2019: Nineteen percent had between US$1 billion and US$5 billion in revenues; 22% had between US$5 billion and US$10 billion; 33% had between US$10 billion and US$25 billion; and 27% had more than US$25 billion.

The survey was fielded in July and August 2020.

© 2021. See Terms of Use for more information.

More from the Financial services collection

-

The path ahead Article4 years ago

-

Preparing for the future of commercial real estate Article4 years ago

-

COVID-19 return-to-the-workplace strategies Article4 years ago

-

Confronting the crisis Article4 years ago