State drug pricing policies Drug companies and PBMs should prepare for continued activity

19 minute read

16 July 2020

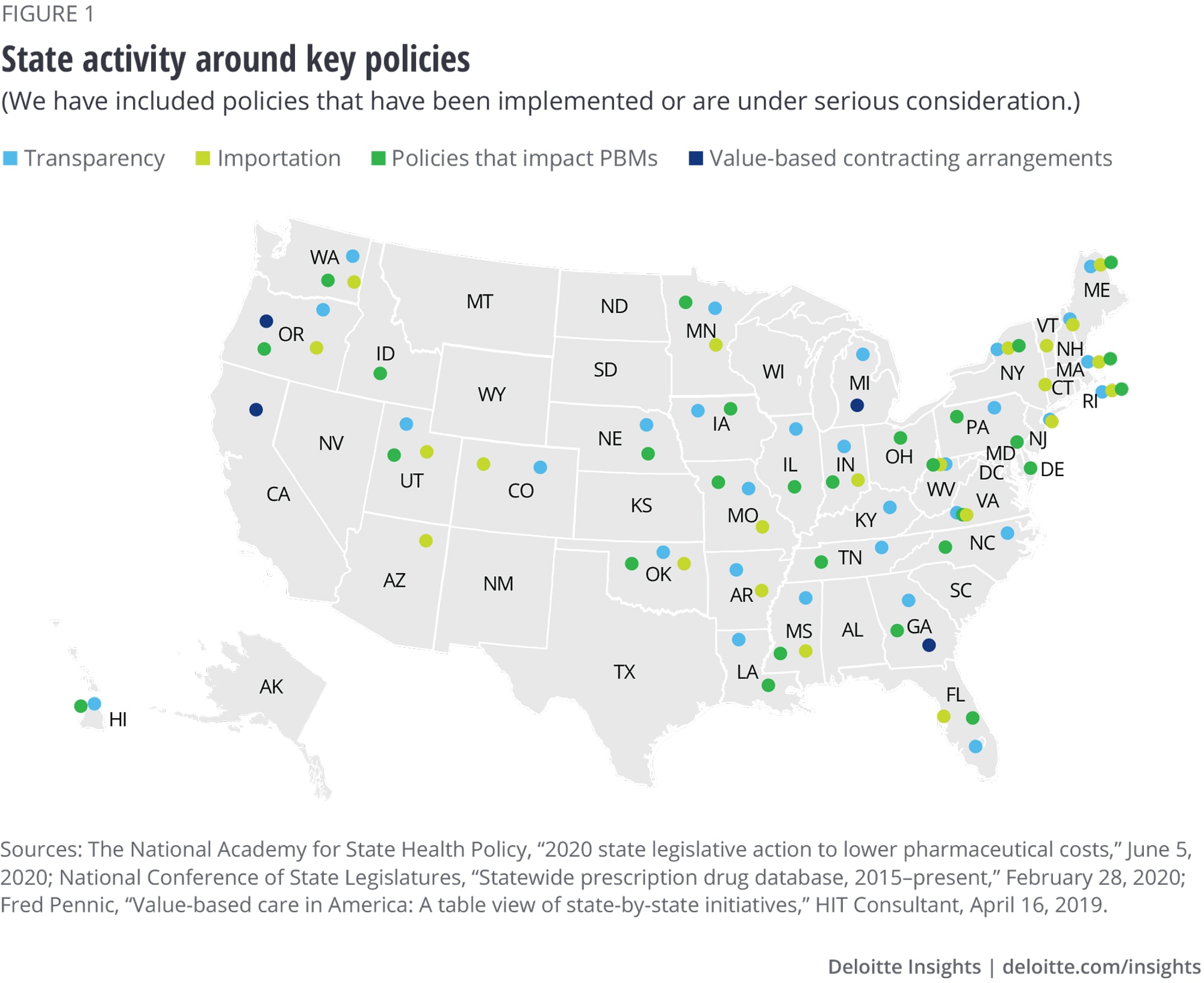

US states are pulling various levers to address rising drug prices. An analysis of public databases and interviews with experts show us the areas under focus, the stakeholders that could be affected, and what strategies they should consider.

Executive summary

Drug pricing proposals at the federal level have stalled, but states have acted to address rising drug prices and are likely to return to this agenda as they find budgets under strain following COVID-19. The Deloitte Center for Health Solutions analyzed publicly available databases and interviewed individuals who have worked on formulating and implementing policies at the state level to find out what legislative and policy proposals have been enacted or are being considered. We discovered there was much activity around drug pricing that could potentially affect pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs), health plans, and drug companies, though the impact on overall spending to date is less clear. Some of the areas where policies have the potential for business model impact include:

Learn more

Explore the life sciences collection

Visit the health forward blog

Learn about Deloitte's services

Go straight to smart. Get the Deloitte Insights app

- Transparency regulations: State transparency regulations require drug companies to report on price increases. Drug companies should be conscious of their pricing strategy and the implications from a legal and public perception perspective. To keep up with new reporting requirements that states might enact and comply with price transparency requirements, companies should consider developing new reporting processes. In fact, many drug companies have begun to explore ways to automate state price transparency processes.

- Policies that regulate PBMs: States will likely continue to assess the impact of moving away from multiple PBMs under contract for Managed Medicaid to a single PBM under fee-for-service (FFS). For PBMs, preparing for continued policy and regulatory activity involves not only compliance but also examining how to continue to show their value story in the services they offer. These could include traditional services that deliver better discounts and use of generic drugs but also value in terms of population health management and clinical outcomes improvement.

- Importation: While importation is in play on the federal and state levels, concerns about safety issues and supply chain and procurement complexities mean these policies likely have less of an impact now.

- Value-based contract arrangements: These arrangements will likely increase at the state level and in the private sector, especially with advances in data analytics. There are a few examples of these in Medicaid today, but the shift to a value-based (or outcome-based) health care system is likely to continue gaining momentum.

With a large number of people losing employer coverage due to the economic factors associated with the pandemic, economists and budget experts expect increases in Medicaid enrollment.1 As Medicaid constitutes a large share of state budgets, we expect scrutiny around drug pricing to increase.

Methodology

The Deloitte Center for Health Solutions analyzed publicly available prescription drug state policy databases, and conducted qualitative interviews with 10 external experts from state Medicaid programs and pharmacy and health plan associations. These interviews occurred from February to March 2020. We also spoke with internal policy experts.

Overview of state policies to reduce spending on drugs

- Transparency: Polices that shine a light on factors affecting drug prices to support pricing levels or increases. Transparency policies often require drug companies to report either price increases of a certain percentage in a given period or estimated costs greater than a set price.

- Importation: Policies that would allow states to buy or import prescription drugs from outside the United States. Though many of these policies focus on importing drugs from Canada, some policies would allow importation from other countries.

- Policies that regulate PBMs: Policies to increase the regulation of PBMs, including increasing rebate and cost transparency, banning spread pricing, and imposing licensing requirements. Policies that impact PBMs constitute the most common legislation passed or under discussion.

- Managing pharmacy benefit design: Policies that enable states to assert their purchasing power through more active oversight of the administration of drug benefits. Much of the focus of these policies is on Medicaid due to the Medicaid Drug Rebate Program, which does not allow states to limit the scope of drugs covered to help control drug costs.

- Value-based contracting arrangements: Agreements in which states and drug companies agree to link payment for a medicine based on a wide range of a drug’s outcomes. These agreements might tie Medicaid payment through the supplemental rebate to a specific, measurable clinical outcome. Sometimes, the manufacturer pays a higher rebate if the drug fails to meet clinical metrics or cost of care benchmarks. Other models involve having rebates structured around patient adherence to a drug therapy regimen.

Transparency regulations could encourage drug companies to keep price increases low to avoid concerns about reputational risk

State transparency policies vary but many focus on reporting requirements for drug companies. Some examples include:

- Advance notice of price increases: Manufacturers planning Wholesale Acquisition Cost (WAC) increases that exceed defined thresholds are required to give advance notice to certain purchasers or state agencies.

- Price increase reporting: Manufacturers that increase the price of a drug at a rate that exceeds a defined threshold (e.g., 20% per unit over a calendar year) are required to report information regarding the drug and the price increase.

- Drug pricing reports: Manufacturers that sell drugs in certain states are required to periodically report pricing to the state.

- Price disclosure to health care providers and states: Requires manufacturers to disclose WAC or the Average Wholesale Price (AWP) to the state or health care providers.

- New drug entry: Triggered when a manufacturer launches a new drug product that has a price that exceeds a specific threshold (e.g., WAC at launch exceeds the Medicare Part D specialty drug threshold).

- Newly acquired prescription drug report: Requires manufacturers to disclose information on acquired prescription drugs whose price exceeds a threshold.

Examples of state activity on reporting requirements for drug companies

In October 2019, Nevada began enforcing penalties under the state’s regulations. To date, the state has imposed more than $17 million in fines on 20 drug companies manufacturing diabetes therapies in relation to noncompliance with drug price transparency reporting. The fines amounted to $5,000 per day, with total fines as high as $910 million for one company.2 Nevada’s enforcement of its laws highlights the compliance and reputational risk in transparency policies.

In Colorado, two policies under discussion would require notification from companies when prices increase above 10% over a 12-month period and penalize PBMs and insurers for failing to provide information about rebates and fees for drugs. In addition, the policy would require prescription drug manufacturers to report drug production cost data to the Department of Health Care Policy and Financing.3

In 2020, the California Office of Statewide Health Planning & Development (OSHPD) began enforcing California’s drug price transparency laws that were passed in 2017. The state has notified some drug manufacturers that they could be assessed fines totalling approximately $17.5 million for failing to comply with the reporting requirements of these laws.4 Because the regulations specify that manufacturers can be fined up to $1,000 per day for failure to submit this information, these fines have accrued into the millions for some manufacturers.

Under these laws, California requires manufacturers to notify the OSHPD when raising prices for existing prescription drugs or when launching a new drug with a price above a specified threshold. Manufacturers are required to report a variety of information including WAC, cost increase factors, history of price increases, and marketing and pricing plans.

States are also creating commission boards or drug affordability review boards to set pricing caps for select higher-cost drugs, as well as limit price increases by drug manufacturers. Indiana, Missouri, Nevada, New Hampshire, and New Mexico are examples of states that have created these boards.5 Maine also worked on a Prescription Drug Affordability Board that sets prescription drug spending targets for public entities based on a 10-year rolling average, considering inflation.6

Effects of transparency policies on drug companies

Transparency policies can affect drug companies in three ways: the cost of compliance reporting, managing negative reputation if the companies’ prices trigger a review, and direct payment of penalties. States with more mature laws have begun posting reported information on public websites and enforcing the penalty provisions contained in these regulations. The penalties for noncompliance vary by state. While certain regulations do not contain specific penalty clauses, most do, and can contain penalties up to US$30,000 per day for noncompliance.

With more states drafting price transparency regulations, drug companies should be conscious of their pricing strategy and the implications from a legal and public perception perspective. Future-enacted regulations may impact future business decisions and pricing strategies. To stay below statutory reporting thresholds, companies might need to consider adjusting pricing strategies.

To comply with new state price transparency requirements, drug companies should consider developing new reporting processes to confirm appropriate information is reported to each state. As states enact new reporting requirements, many companies have begun to explore ways to automate state price transparency processes, including having pricing and reporting information in one centralized repository via a system or tool.

In addition, the pharmaceutical industry has said these types of reviews could risk stifling innovation in research and development and could limit access to new age drugs and therapies.7

Importation could expand access to prescription drugs, but there are many challenges

In response to some Americans traveling to Canada to buy cheaper drugs in the early 2000s, states, PBMs, and the federal government have explored the feasibility and safety considerations around importation.

State activity and progress

Florida has passed legislation on importation, and many other states are exploring importation, including Colorado, Maine, New Mexico, and Vermont.8 Before any state’s plan can go into effect, the secretary of the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) must certify that the plan meets certain safety and cost-saving requirements. To date, no state’s plan has been certified, and some states are waiting for additional guidance.9

Florida’s House Bill (HB) 19 establishes two programs to import drugs approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to Florida: The Canadian Drug Importation Program (CDIP) and the International Prescription Drug Importation Program. The CDIP focuses on bringing down the cost of drugs for state-funded programs, such as Medicaid and the state prison system.10 The process includes selecting a vendor and identifying eligible importers and Canadian suppliers. The program establishes criteria for eligible prescription drugs as well as requirements for distribution and supply chain documentation. The program is compliant with federal tracking and tracing requirements.

The International Prescription Drug Importation Program is a pilot program that started in 2019 and is open to individual Florida residents and those participating in the CDIP. The program allows wholesale distributors, pharmacies, and pharmacists to import prescription drugs into the state, and prescription drug wholesale distributors, nonresident prescription drug manufacturers, and international export pharmacies to export prescription drugs.

HB 19 also enacts a pilot program for the Florida Department of Business and Professional Regulation and the Department of Health to negotiate a federal arrangement for importing prescription drugs to Florida entities licensed to manufacture, distribute, or dispense prescription drugs.

In March 2020, Oklahoma proposed a bill (SB 940) that authorizes any licensed pharmacist and wholesale drug distributor in the state to import prescription drugs from a certified Canadian supplier and to distribute these drugs to patients or licensed pharmacists in Oklahoma. The bill specifies that individuals can only get imported drugs from a certified Canadian supplier and that only licensed wholesalers, pharmacies, or pharmacists can import drugs. It stipulates penalties for violating this provision.11

In late 2019, the Trump administration issued a notice of proposed rule-making that would allow importation of prescription drugs from Canada if finalized.12 Another pathway proposed by the Trump administration outlines how manufacturers can import and market FDA-approved prescription drugs in the United States that were manufactured abroad and intended to be marketed and authorized for sale in a foreign country. Until federal rules come out, states cannot move forward on these policies, so they have not affected drug companies.

Some critics have raised concerns about the impact of these programs on drug pricing and access in Canada. Some other operational questions include:

- Supply chain issues: Who bears the procurement, shipping, and dispensing costs, and how would dispensing work?

- Safety and quality of drugs: How to ensure that counterfeiting does not occur and drugs that are brought from Canada are from reliable sources?

- Inventory segregation and issue for retailers: If the prescription drugs are imported from Canadian wholesalers by various US pharmacy retailers, how will the retailer differentiate what drugs (i.e., via Canada or within the United States) are for the importation program/population

- Prescribing process: Is it prescribed by a US doctor and filled in Canada and shipped to the patient, or is it prescribed in Canada, imported, then labeled and fulfilled?

- Savings: Will the savings be on many drugs or just a few? Will the additional costs of the supply chain and shipping get rid of any savings on generics?

Some stakeholders, including some consumer advocacy groups and business groups, support importation. Opponents include some drug companies, retail pharmacy associations, and physician specialty societies, who have cited concerns about patient confusion and potential for disruption in care. The Canadian government has also voiced concerns about impact to its drug supply.

Many policies focus on increasing regulation of PBMs

Some states are exploring policy levers they could use to regulate PBMs.13 Polices developed to regulate PBMs can be categorized under:

- Transparency requirements: Many states have passed policies that require PBMs to report to health plans and state agencies. Some states provide health plans access to all financial and utilization information of a PBM for services provided to the plan. Policies also require PBMs to provide plan sponsors with deidentified claims information that differentiates between payments made to pharmacies owned or controlled by the PBMs and those not affiliated with the PBM.14

- Licensure requirements: PBMs need a license to operate in a state, which acts as a lever in PBM regulation as it defines aspects of PBMs’ operating models. It also gives the state power to suspend or revoke a license in case of fraudulent activity.

- Policies that target “spread pricing”: Some of these policies aim to have less opaque PBM payment practices. They target the profits PBMs make from the “spread in pricing” (the difference between the amount a PBM pays a pharmacy when a prescription is bought versus what it charges the employer or the state).

- Shifting from PBMs to FFS in Medicaid: Some states are assessing the impact of moving away from multiple PBMs under contract with the Managed Medicaid company to a single PBM under FFS (i.e., carving pharmacy out of managed care).

State activity and progress

Maine passed a law that targets spread pricing and requires more transparency from PBMs around their relationship with insurers. It also requires insurers that contract with PBMs to monitor the PBMs’ activities. The law prohibits PBMs from retaining rebates from drug manufacturers and calls for them to pass those savings on to the consumer or health plan. The law also contains licensing requirements for PBMs, to give the state visibility into how many and what entities are operating as PBMs in the state.15

In early 2019, California state governor Gavin Newsom released an executive order to carve out pharmacy benefits for Medi-Cal beneficiaries (California’s Medicaid program) from managed-care plans to FFS, contracting with a single PBM. Under the order, by January 2021, all prescription drugs dispensed to Medi-Cal enrollees at pharmacies will be paid through FFS. In the past, California has worked with more than 20 managed-care organizations, who then contracted with 10 PBMs. One goal of the order was to improve Medi-Cal stakeholders’ access to drugs and pharmacies. One study estimated the state would potentially save hundreds of millions of dollars annually; however, the study cited a number of unanswered questions, particularly about how the carve-out will impact the coordination and management of beneficiary care.16

PBMs should consider developing business models that demonstrate their value story

While we saw a lot of federal activity focused on PBM rebates in 2019, for the most part those proposals were taken off the table. However, knowing the issue of pricing is not likely to go away, PBMs are considering redefining the services they offer.17 Some PBMs are trying a rebate-at-the-point-of-service model or establishing formularies that reduce the influence of rebates, according to Deloitte’s recent report on optimizing drug market access.18 Many PBMs have developed formularies that try to shift away from products with high list prices and high rebates toward products with lower list prices. Moving forward, PBMs will likely have to think about how to keep innovating to address unmet needs in population health management and clinical outcomes improvement while continuing to explore the broader role of pharmacists and pharmacies in overall care management.19

PBMs should consider highlighting their value stories, including the tools they use to ensure that patients receive the right drug, determine cost-sharing in real time, and use data on medication adherence to improve outcomes.

Supreme Court agrees to hear a case involving states’ attempts to regulate PBMs

Oral arguments for Rutledge v. Pharmaceutical Care Management Association (PCMA) began in April 2020. The Rutledge case will determine the validity of an Arkansas law regulating aspects of PBMs’ business. For example, the law calls for PBMs to pay pharmacies the wholesale cost or above for generic drugs. At least 38 states have passed similar legislation on PBM activities.20

The PBM trade group PCMA filed a suit in response to Arkansas’ law. PCMA claims the federal Employee Retirement Income Security Act (ERISA) of 1974, which sets minimum standards for most employer-sponsored health plans, preempts Arkansas’ legislation.

Rutledge appealed the ruling with support from more than 30 state attorneys general.21 After the Supreme Court decided to take the case, PCMA released a prepared statement criticizing Arkansas’ law.22 According to the group, “Unique state laws governing the administration of pharmacy benefits are proliferating across the country, establishing vastly different standards. These inconsistent and often conflicting state policies eliminate flexibility for plan sponsors and create significant administrative inefficiencies.”

According to some legal newsletters, the court’s ruling in Rutledge could help clarify whether states can regulate PBMs that provide benefits for ERISA-governed health plans.23

Some state Medicaid programs are exploring value-based contracting arrangements, though barriers remain

Pricing pressure has compelled drug companies to explore alternative payment models, including value-based contracting arrangements, which are agreements in which states and drug companies agree to link payment for a medicine based on a wide range of a drug’s outcomes. Due to increased Medicaid spending,24 state Medicaid programs are starting to experiment with their own value-based arrangements for prescription drugs to control costs. For a state to implement these arrangements, they must apply for and get approval from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) in one of two ways:

- A state plan amendment for approval, which is an agreement between a state and the federal government outlining how the state will administer its Medicaid and Children's Health Insurance Program (CHIP) business, to include the implementation of value-based contract arrangements

- A Section 1115 demonstration waiver, which allows states the flexibility to design and improve their programs, including implementing these types of arrangements.25

While states are exploring and implementing alternative payment arrangements to control costs and improve patient outcomes, it is difficult to assess how much states are saving or could be saving under this model due to lack of measurable outcomes data.

State activity and progress

Since 2018, several states, including Colorado, Michigan, and Oklahoma received approval from CMS for their state plan amendments to adopt alternative payment models focused on patient outcomes.26 These states can negotiate supplemental rebates based on clinical outcomes for patients receiving specific drugs.

In 2018, Oklahoma was the first state to have a plan amendment approved by CMS, which enabled the state to implement four outcomes-based contracts for anti-psychotics and bacterial skin infection drugs. The short-term goal was to improve patient outcomes with lower drug prices, and the long-term goals included targeting the most appropriate intervention in specific patients for lower overall program costs. The program has faced many challenges since its implementation, including some drug companies’ reluctance to enter into such agreements, and the lack of measurable and meaningful outcome from claims data. To get a better perspective on outcomes, the state partnered with the University of Oklahoma and State Medicaid Alternative Reimbursement and Purchasing Test for High-cost Drugs (SMART- D) initiative to identify appropriate outcome measures from data sources.27 While data is limited, one company contracted with Oklahoma agreed to continually increase rebates if the prescription is refilled each month. This agreement helps increase patient outcomes and reduce state spend.

Colorado and Michigan have also been approved by CMS to negotiate supplemental rebates through value-based contract arrangements. According to their state plan amendments, outcomes vary but are measured through patient adherence or reduced hospitalizations. If performance does not meet the standards expected by the state, the manufacturer pays the state back through supplemental rebates. Neither state has initiated contracts yet.

Considerations for drug companies as value-based contract arrangements continue to grow

We learned from our interviews that value-based contract arrangements raise many challenges, including the need for large sets of patient data to properly negotiate the contracts, the inability to measure outcomes due to lack of measurable outcomes through claims data, and patients switching health plans, which makes outcome tracking difficult.

While the number of publicly announced value-based contract arrangements between drug companies and payers has increased over the past few years, barriers continue to prevent widespread adoption. Previous Deloitte research has shown that one potential strategy to increase the adoption of value-based contract arrangements would be for industry players to share the successes and failures of these arrangements more widely—that all stakeholders could benefit from greater transparency around what works and what doesn’t. Expanding the conversation to other stakeholders who play key roles—such as PBMs, large employers, states, regulatory agencies, and clinicians—could lead to greater success in the future. Advances in cloud-based technology, automation, and data analytics are making it more possible than ever to create a trusted, secure environment to design and implement these arrangements in the public and private sector. The proliferation of these arrangements has the potential to help control costs, create access to care, and improve patient outcomes.28

Health care stakeholders should consider strategies that continually demonstrate their value stories to consumers

While the drug pricing proposals we examined most directly impact drug companies and PBMs, there are also implications for retail pharmacies and health plans. PBMs should consider emphasizing the value mail-order pharmacy brings to consumers and their increasing ability to connect with patients with virtual visits. Mail order and virtual visits have been critical to many patients since COVID-19 began impacting the United States.29

Health plans could potentially evolve to focus more on encouraging consumers to make healthier decisions by using automation and artificial intelligence to help identify members due for preventive health services, or for medication reminders. Health plans are increasingly offering wellness and chronic disease management programs that help support members in their quest to maintain or improve their health. Health plans could also potentially take on a larger role in supporting members in addressing the drivers of health, or the factors outside the traditional health care system that impact our health, such as food security and nutrition, education, accessible and safe housing, employment, transportation, meaningful relationships, and a sense of community.

Where might states, drug companies, and other health care stakeholders go from here?

There continues to be much interest among states to address drug pricing. Because of the complexity of the health care system, many states are finding it challenging to get beyond a whack-a-mole approach and find holistic solutions to drug pricing. Some of the interviewees we spoke with mentioned that federal legislation might provide a more holistic approach, as it can be hard for states to impact pricing on their own. With the 2020 election coming up, we might hear of more federal proposals to address drug pricing, including the International Price Index (IPI). The basic idea of these proposals would be to choose the price that the United States pays for a set of particular drugs covered under Medicare based on the price paid in other countries. Both the House of Representatives and the Trump administration have touted IPI proposals in 2019.

We expect states to redouble efforts on drug pricing as the COVID-19 crisis ebbs. As the United States moves toward recovery and looks ahead to make changes to the health care system, drug companies and PBMs should anticipate growth in the push to show value in the long run.

Our research shows:

- Transparency and managing pharmacy benefit programs are leading to the biggest changes in today’s business models. Some of the state transparency regulations can be challenging for drug companies due to the complexity of reporting and compliance requirements. These policies could have implications for drug company pricing strategies from a legal and public perception perspective. Drug companies should consider developing new reporting processes to ensure appropriate information is reported to each state. As states enact new reporting requirements, many drug companies have begun to explore ways to automate state price transparency processes, including having pricing and reporting information in one centralized repository.

- Policies that impact PBMs are likely to continue. States will likely continue to assess the impact of moving away from multiple PBMs under contract with the managed-care organization to a single PBM under FFS. To prepare for continued policy and regulatory activity, PBMs should continue to consider how they can redefine the services they offer, and drug companies will likely have to think about how to keep innovating to address unmet needs in population health management and clinical outcomes improvement.

- Value-based contract arrangements will likely increase, especially with advances in data analytics. While these arrangements are currently few, the focus on getting more value from therapies shows no signs of slowing. The proliferation of these arrangements has the potential to help control costs, create access to care, and improve patient outcomes especially as we look at high-cost specialty medications and cell and gene therapies. Expanding the dialogue around how to get the best value from the system to the broader ecosystem—including drug companies, PBMs, large employers, states, regulatory agencies, and clinicians—could lead to greater success with value-based contract arrangements in the future. Drug companies should consider collaborating with states and private payers to expand value-based contracts. Companies should also consider enhancing their ability to generate new types of data, including real-world data, to demonstrate their product’s value story, and offering solutions to help consumers better manage their disease or condition, through care delivery or disease management programs.

- The future of importation remains unclear. The Trump administration continues to consider importation proposals, and some states have moved ahead with their policies. However, concerns about safety issues as well as supply chain and procurement complexities have resulted in smaller impact from these policies to date.

© 2021. See Terms of Use for more information.

Explore more articles on life sciences

-

AI in Biopharma Collection

-

Winning in the cell and gene therapies market in China Article4 years ago

-

The future of biopharma Article4 years ago

-

New payment models in medtech Article5 years ago

-

Intelligent clinical trials Article5 years ago