The ears have it: The rise of audiobooks and podcasting TMT Predictions 2020

16 minute read

10 December 2019

The audiobook and podcasting markets are growing far faster than the overall media and entertainment market. What's so special about listening?

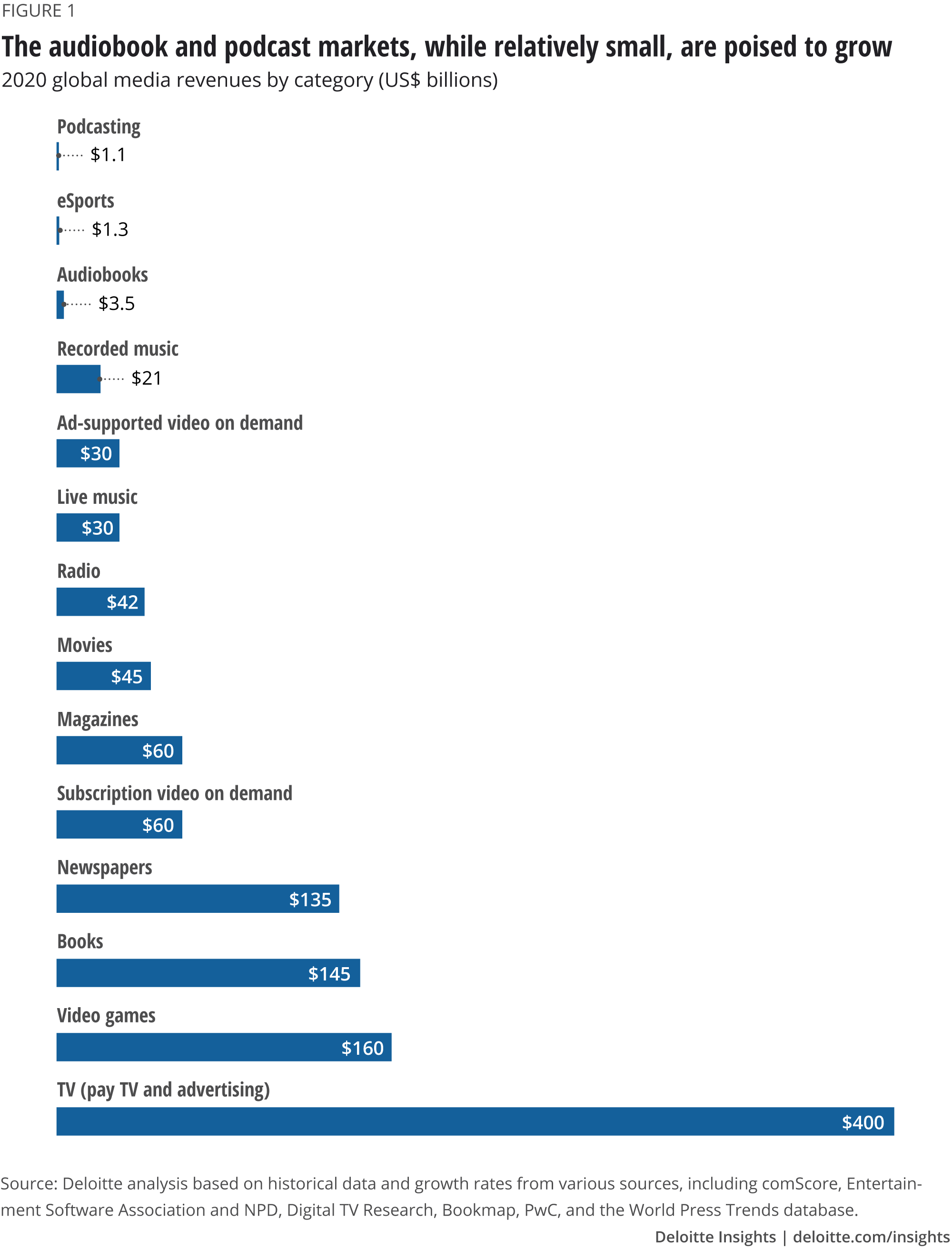

The next time you settle down with a good book, will you reach for a set of headphones instead of an eReader? Audiobook publishers are hoping so—and the market’s anticipated growth lends weight to their aspirations. In 2020, Deloitte predicts, the global audiobook market will grow by 25 percent to US$3.5 billion. And audiobooks aren’t the only audio format gaining in popularity. We also predict that the global podcasting market will increase by 30 percent to reach US$1.1 billion in 2020, surpassing the US$1 billion mark for the first time.1

These numbers may not look like much next to radio’s US$42 billion and music’s (recorded and live) US$51 billion global annual revenues (figure 1). But in a world where overall media and entertainment growth stands at just 4 percent,2 25 to 30 percent annual growth is impressive, even considering the low absolute base. The signal is clear: Audiobooks and podcasts are outgrowing their “niche” status to emerge as substantive markets in their own right.

Learn more

View TMT Predictions 2020, download the report, or create a custom PDF

Download the infographics

Watch the video on this year’s TMT Predictions

Download the Deloitte Insights and Dow Jones app

Subscribe to receive related content

Hearing is believing

The anticipated growth in audiobooks and podcasts is part of a larger trend of better-than-you-might-think growth in audio overall. In the United States, for instance, recorded music revenues grew by 12 percent in 2018;3 vinyl record revenues went up by 8 percent, showing that even physical music media can still have consumer appeal. And although neither global radio revenues nor global concert ticket sales are increasing at the same rate, both are still growing a few percentage points faster than global TV and global (printed) book revenues, and 10 to 20 percentage points faster than global magazine and newspaper revenues (as the latter markets are contracting).4 Meanwhile, 2018 headphone sales reached US$20 billion in the United States alone, up 27 percent year over year. People use headphones for more than just podcasts or audiobooks, of course … but they do illustrate how important our hearing is.5

All this goes to show that audio is anything but dead. To paraphrase what we said about radio last year: “Audio is the voice whispering in our ear, in the background of dinner, in an office, or while driving the car. It is not pushy or prominent … but it is there.”6 Silence may be golden, but it’s not necessarily the most interesting thing to listen to while commuting, doing chores, or working out.

Audiobooks and their listeners: Ripe for continued growth

The United States’ audiobook market—predicted at US$1.5 billion in 2020, and growing at a seemingly sustainable 20 to 25 percent per year for the next few years—is the world’s largest. Coming in second is the Chinese audiobook market, expected to generate about US$1 billion in the same year, up from US$450 million in 2017.7 Outside these two well-studied markets, data is sparse and the markets themselves more nascent. Data gleaned from various sources suggests that annual audiobook revenues in the four Nordic countries are running at about US$100 million;8 the UK audiobook market was about US$85 million in 2018,9 with audiobook revenues for all of Europe (including the United Kingdom) grossing about US$500 million.10 Based on these figures, a global audiobook market of US$3.5 billion seems reasonable, with the United States and China making up about 75 percent of it.

The audiobook market isn’t just about dollars; it’s about listeners as well. According to a 2018 survey, 18 percent of American adults said that they listened to an audiobook in the last 12 months, up four percentage points since 2016.11 Assuming this growth rate has held steady, these figures imply that more than 73 million people listen to an audiobook at least once a year in the United States today. Likewise, data from China suggests that 22.8 percent of the population listened to at least one audiobook in 2017.12 Assuming similar growth, likely more than a quarter of the Chinese population, or another 350 million people, listens to audiobooks today. Globally, the number of current audiobook consumers almost certainly exceeds half a billion.

In the longer term, we expect double-digit growth in audiobooks to continue, even if it slows somewhat from 2020’s torrid 25 percent pace. US audiobook revenues, for instance, have grown at double digits almost every year since 2013, and even accelerated to nearly 40 percent in 2018.13 The spread of smart speakers is one likely driver, as are streaming-books-on-demand (SBOD) models that offer monthly subscriptions. Globally, too, growth is likely to accelerate as other countries and regions catch up to the levels seen in the United States, China, and the Nordics.

Audiobook consumption will likely differ across geographies and demographics. In 2019, for example, 74 percent of audiobook listeners in the United States listened to them in their cars.14 Countries where commute times are longer may thus see higher revenues, growth rates, and opportunities for audiobooks than countries with shorter commutes. Children’s audiobooks, too, which already represent a substantial fraction of the total number of audiobooks sold, may also be a growth hotspot: In 2017, this category made up 40 percent of the audiobook titles sold in China, 10 percent in the United States, and 25 percent in France.15

Interestingly, while audiobooks are rapidly gaining share in both the book market and the overall media market … that share isn’t coming from print books. As an example, in the United States, revenues from sales of print books for consumers (trade books) in the first six months of 2019 rose by 2.5 percent year over year, even as revenues from downloaded audiobooks also increased by 34 percent. E-book revenues, however, went down by 4 percent in the same period (although e-books still made 77 percent more money than downloaded audiobooks).16 It appears that, while hardcore print lovers are clinging to the physical page—which is still the dominant form of consumption, accounting for 78 percent of all US trade book revenues overall—a war in the digital arena is underway between those who want to use their eyes versus those who prefer their ears. The outcome? No one knows for sure yet—but at current growth rates, audiobook revenues are on a trajectory to pass e-books by 2023 or so.

Podcasts and the monetization question

With anticipated revenues of just over US$1 billion in 2020, podcasts barely make enough money today to rate a slot on the media formats list. But if future growth remains as high as in the past few years, podcasts could be a US$3.3 billion–plus business by 2025.17 For this to happen, however, the podcast industry should further expand globally, add new listeners, and—most crucially—get better at monetizing (at least to some extent) its large listener base.

So let’s talk about podcast monetization, especially in contrast to audiobooks. Audiobook pricing models come in two basic forms: The consumer either purchases audiobooks outright, or streams them through a monthly subscription service such as Audible, Scribd, or Kobo. Purchasing a high-quality audiobook outright usually costs US$20–30—always more expensive than a paperback or e-book, and indeed often with a 50 to 100 percent premium over them.18 And while prices and features for the monthly services vary, US$9–15 per month (or well over US$100 per year) is about average.

Podcasts, on the other hand, have multiple revenue streams: advertising and sponsorships, subscriptions, events, merchandise, content marketing, contracts for branded podcasts, and individual listener donations.19 Of these, advertising and sponsorships are by far the largest, although exact splits by revenue stream do not seem to be publicly available.

With all these different revenue possibilities, one might think that podcasts would have no problem monetizing their listeners. Wrong. Although the United States in 2018 had 60 percent more podcast listeners than audiobook listeners (21 percent of Americans for podcasts versus 13 percent for audiobooks), podcast revenues for that year were roughly 33 percent lower than for audiobooks (US$500 million compared with US$750 million). This means that each audiobook listener generates more than 2.4 times the annual revenue of a podcast listener. And it isn’t just audiobooks that podcasts lag behind when it comes to monetization. In the United Kingdom in 2017, commercial radio generated 2.8 pence of ad spend per hour of listening, while podcasts generated just 0.5 pence.20

Is that about to change? Possibly. Although podcasts have been around since 2004,21 podcasters have only really pursued making money from them since about 2015—prompted largely by the success of 2014’s Serial, which was the first single podcast to gain a large enough audience to attract advertisers. As podcasters get more serious about revenue generation in the future, they will presumably become better at optimizing their various revenue streams. And global podcast revenues in 2013 totaled only about US$45 million, giving podcasts plenty of room for growth.22 (That said, estimates for US podcast ad revenues predict decreasing growth rates over time, slowing from more than 50 percent growth in 2018 to about 20 percent by 2021.)23

Podcasts also cost less to make than audiobooks, as a rule. Even podcasts with higher production standards and better-known hosts hardly compare with most audiobooks’ production costs. To create a 10-hour audiobook (containing about 75,000 words, equivalent to about 300 pages), a publisher typically pays between US$3,000 and US$15,000, factoring in the cost of narration, editing, recording, and mastering.24 Audiobooks narrated by celebrities (including Claire Danes, Meryl Streep, Samuel L. Jackson, Ian McKellen, and many others) can be more expensive still.

However, we believe that podcasts will have a very hard time catching up to audiobooks’ ability to monetize listeners. One of the biggest difficulties is simply the sheer number of podcasts that are available for free. Because the barriers to podcasting are low, anyone can (and a great many do) make them: As of 2019, more than 700,000 podcast series encompassing 29 million episodes were active, and most were basically free for the listening.25

What’s more, many of these free podcasts are of surprisingly high quality. Broadcast radio, for instance, is an excellent source of high-quality podcasts. It’s easy for broadcasters to “podcast-ify” a radio episode after it airs (for minimal cost) and put it on their website—and if it’s a public broadcaster (such as BBC, NPR, and CBC), the podcasts are often free, with no subscription charges and no ads. The newspaper industry, too, contributes to this phenomenon. Although some newspapers charge for their podcasts, many others offer them to subscribers for free (though with ads) as a way to attract and retain digital subscriptions, or to encourage subscribers to pay more for a premium tier.26

Enterprise podcasting is yet another source of free podcast content. Businesses tend not to include ads in or charge subscriptions for their podcasts. They almost invariably give them away for free—but that doesn’t mean they are without value!

The upshot: So long as people can listen to thousands of hours of high-quality podcasts essentially for free, profit-motivated podcasters will have a hard time getting listeners to actually pay for content.

Enterprise podcasts: Are they really worth a billion dollars?

Enterprise podcasts may seem odd to mention at all in this chapter, considering that they generate no (direct) revenue and that global corporate spending on them probably totals no more than tens of millions of dollars per year. But if we view them as vehicles for marketing, brand-building, training, and recruiting, we are looking at an industry that creates value for enterprises of all stripes, as well as for their customers and current and prospective employees. Although it’s impossible to measure that value precisely, we can make an educated guess. If millions of people are listening to enterprise podcasts, as is likely, then the value being generated for the enterprises making these podcasts could be close to US$1 billion, or about the same size as the consumer podcast market.

As of 2019, enterprise podcasting is already mainstream. Of the 25 largest Fortune 500 companies, 17 (68 percent) hosted their own podcasts on their corporate websites.27 To be clear, these are podcasts produced and paid for by the companies themselves, not company CEOs appearing in third-party podcasts or companies sponsoring the production of an independent podcast series. The trend seems to cross all industries: Both B2B and B2C companies produce podcasts, with retail, health care, energy, telecom, financial services, manufacturing, automotive, and technology all represented. However, within any particular industry, companies’ podcasting efforts vary widely. While one major auto company might have several podcast series, another of roughly the same size may have none. The one industry where this hit-or-miss pattern does not hold is professional services. All of the world’s largest law, tax and accounting, and consulting firms have enterprise podcast series. And not just one or two: Almost all of these firms have dozens or even hundreds of series, each with multiple episodes, and each usually associated with a specific service line.

These enterprise podcasts have three main uses. First, companies produce podcasts for marketing purposes: to demonstrate their knowledge, showcase their expertise, and generally build their brand. Second, podcasts can support internal education as a way to deliver e-learning content. And finally, many businesses use podcasts as a recruitment tool.

Businesses spend substantial sums of money on all three of the above activities, which means that they certainly have the funds to produce many podcasts. Large enterprises spend more than US$1.6 trillion globally on marketing each year,28 while the global training/e-learning market and the global recruiting market each attracts US$200 billion of corporate spending annually.29 Podcasts are only ever going to be a small percentage of that overall spend, but that may still prove to be a surprisingly large amount.

The return on investment (ROI) on enterprise podcasts is likely to be quite high, especially given how inexpensive they typically are to make. Audio recording equipment and technology is typically cheap, editing is relatively easy compared to that for videos or audiobooks, and a single corporate podcast host (who likely does other tasks as well) can record hundreds of episodes firmwide each year. But what makes podcasts especially economical is that businesses have likely already invested millions of dollars in creating content and building expertise that might make for compelling podcast material. A company might spend tens or hundreds of thousands of dollars to conduct a single research study, print out tens of thousands of dollars’ worth of reports based on the study, and spend tens of thousands of dollars more on videos to promote the study. Spending an incremental US$500 on a podcast is such a low additional cost that triple-digit ROIs seem almost assured.

The catch is that measuring this ROI, as mentioned above, is essentially impossible. Besides the fact that the value they generate is mostly intangible, it’s difficult, if not impossible, to tease out podcasts’ specific role in the overall process of building an organization’s brand, enhancing its reputation as a thought leader, increasing its employees’ skills and knowledge, and getting a foot in the door with prospective clients and employees.

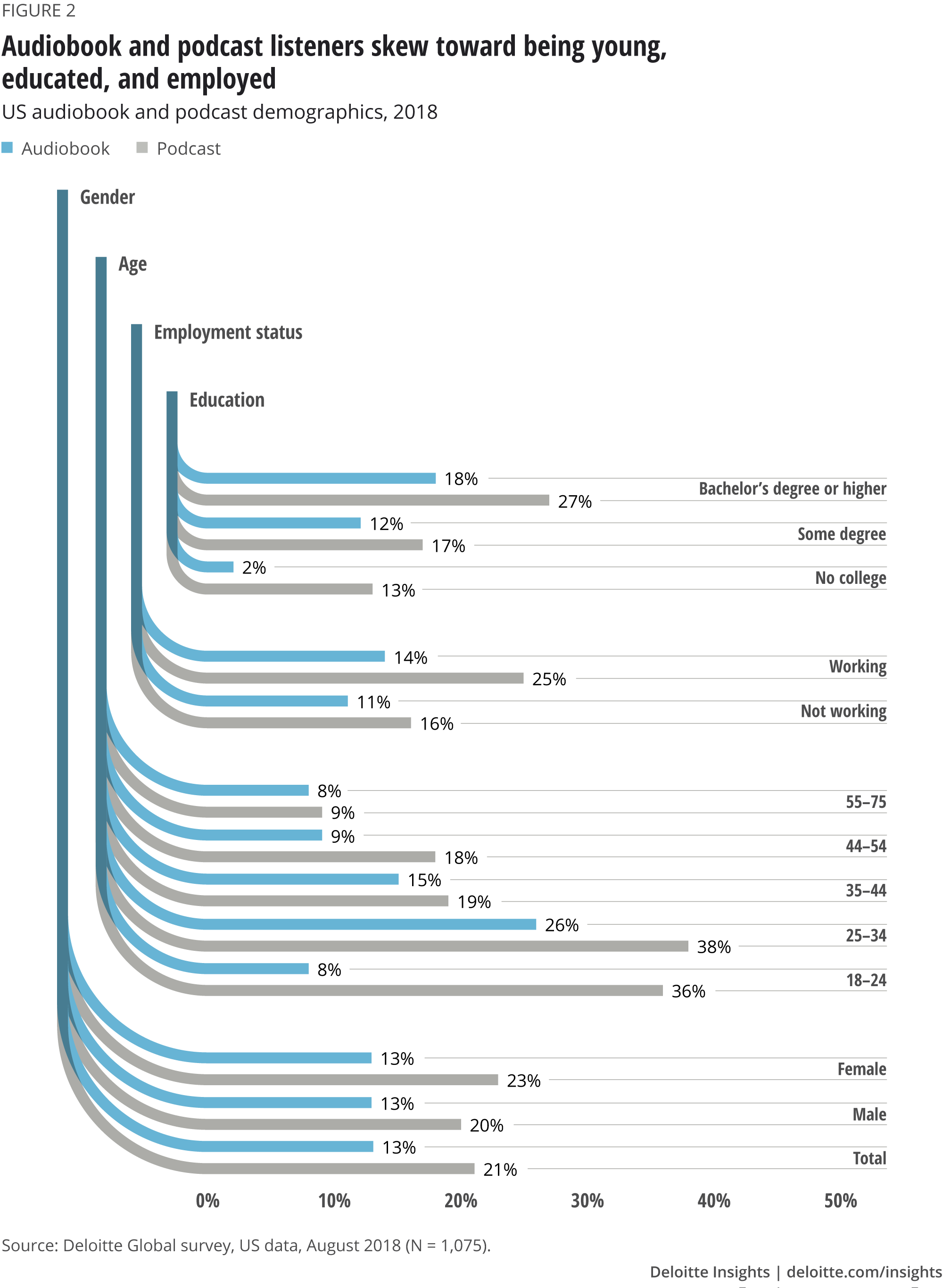

Still, we expect growth in enterprise podcasting to be much higher than in nonenterprise podcasting due to the overall podcast audience’s demographics. The kinds of people who often listen to podcasts—young, educated, and employed—are also the kinds of people whom companies find desirable as both prospective customers and employees. They can be an attractive audience to many advertisers as well, which explains why ad revenues for podcasts in general are expected to grow faster than for many forms of traditional media. To enterprises looking for long-term employees—not just buyers of a product—the podcast audience’s demographics may prove an even more irresistible lure.

A young, employed, and educated customer base

From whom do audiobooks and podcasts make their money? To find out, Deloitte Global conducted a survey of more than 1,000 adults in the United States in 2018. The results suggest that audiobook and podcast listeners skew toward being younger, more educated, and employed (figure 2)—all attributes that make them an attractive customer base.

The above generalization, of course, masks certain nuances. For instance, audiobook listenership among the youngest cohort surveyed, 18–24-year-olds, is markedly lower than among the next older cohort of 25–30-year-olds; only eight percent of US 18–24-year-olds listen to audiobooks, about the same proportion as 44–75-year-olds. One possible explanation is that many 18–24-year-olds are still in school and spend most of their reading time studying printed textbooks rather than listening to audiobooks for pleasure. Also surprising is that, although some have suggested that audiobooks would be a boon for seniors (due in part to age-related vision loss) 30 and those with lower levels of literacy,31 the survey data showed that neither those aged 55–75 nor those with no postsecondary education (a group likely to overindex on illiterate or low-literacy readers) are embracing audiobooks en masse—at least not yet.

Of the 21 percent of adult Americans who listen to podcasts, most are doing so regularly. Thirty-eight percent of surveyed podcast listeners reported listening daily or almost daily, 66 percent at least once a week, and 87 percent at least monthly. These frequencies were generally consistent across gender, education, and work status … with one exception. Only about 40 percent of 55–75-year-old podcast listeners do so at least weekly, making this age group not only the least likely to listen to podcasts at all, but the least likely to listen to them frequently.

These general patterns also hold in Canada. When the same survey polled more than 1,000 Canadians (also in 2018) about their audiobook and podcast listening habits, it found that, while the proportions of both audiobook and podcast listeners were about 2–3 percentage points lower across groups, the overall distribution was similar to that in the United States.

The bottom line

For audiobook publishers, the audiobook market’s growth prospects in 2020 and beyond will certainly be music to their ears. To compete effectively for listeners and dollars, however, they should determine not only which titles to release as audiobooks, but also how many and how often. If 46,000 new titles per year is reasonable for the United States, are 650 local-language titles for Spain or 95 per year for India the right numbers for those countries?32 Whatever that number turns out to be, it will probably get bigger from year to year. The cost of producing an audiobook is not negligible, but it is quite small compared to the cost of advances, promotion, and printing for traditional books, so we expect the percentage of titles that are made into audiobooks to rise over time.

As for podcasts and their monetization prospects, various structural headwinds suggest that the revenue gap with audiobooks, while it may narrow, will not close. Higher production values may help: Too many podcasts have very low-quality sound, and moving closer to the recording techniques used for audiobooks may allow for higher pricing.33 Another possible strategy is to reduce quantity while increasing quality. News UK, for instance, halved the number of podcasts it makes and saw downloads double while ad revenue tripled.34 Indeed, it seems likely that higher-profile podcast producers may start curating their podcasts more thoughtfully, resulting in fewer but higher-quality podcasts on the market overall. Signs also point to a possible decline in user-generated podcasts. Many newer podcasts are interview-style podcasts (aka “bantercasts”) that are insufficiently differentiated to compete in an already overcrowded market, and industry experts are predicting that many of these, having failed to attract audiences or advertisers, will simply stop being updated, a phenomenon known as “podfade.”35

Both audiobooks and podcasts may receive a boost from the continuing spread of smart speakers. Smart speakers are expected to achieve more than 25 percent market penetration in the United States and urban China by 2020,36 and more growth is anticipated as the rest of the world catches up. These devices are popular with audiobook and podcast listeners, with 66 percent of smart speaker owners in the United States saying they listen to at least one audiobook or podcast on their smart speaker weekly.37

Finally, how worried should the rest of the audio industry be? That depends on where audio and podcast listeners are coming from—but the radio industry, in particular, may have reason for concern. Although radio has proven surprisingly resilient compared to other traditional media, with current revenues of US$42 billion globally and slow but steady growth expected on the back of its 90 percent-plus global weekly reach, recent data shows some worrisome signs. While the decision of what to listen to is not an all-or-nothing choice—90 percent of US podcast listeners have also listened to radio in the last week, for instance38—radio’s total listening minutes are declining. In the first quarter of 2019, average radio listening time in the United States fell by four minutes per day to 1 hour and 42 minutes, down 3.8 percent year over year. This decrease, moreover, occurred among all age groups, with the steepest declines among 18–34-year-olds and 35–49-year-olds (5.9 percent and 4.5 percent, respectively).39 Given that two-thirds of all out-of-home US radio listening occurs in cars,40 and that podcasts and audiobooks serve a function similar to radio during commutes, it’s at least plausible that radio’s decrease in listening minutes reflects a loss of listeners to audiobooks or podcasts. For radio broadcasters, these numbers may be worth watching closely as audiobooks and podcasts continue their upward climb.

Explore the collection

-

My antennae are tingling: Terrestrial TV’s surprising staying power Article4 years ago

-

Robots on the move: Professional service robots set for double-digit growth Article4 years ago

-

Bringing AI to the device: Edge AI chips come into their own Article4 years ago

-

Ad-supported video: Will the United States follow Asia’s lead? Article4 years ago