The home-based worker Resetting ways of working

5 minute read

22 January 2021

As COVID-19 forced millions of people to work from home, the advances in digital technology that made this possible—and effective—have never been more apparent.

Explore survey results from specific countries

In 2020, COVID-19 obliged hundreds of millions of citizens around the world to change their working patterns—in some cases literally overnight. 2020 has been a harsh year for many, but, for those able to do so, being able to work remotely has made possible a degree of continuity in their working lives.

Learn more

Explore the Telecom, media & entertainment collection

Learn about Deloitte’s services

Go straight to smart. Get the Deloitte Insights app.

The speed and, for the most part, effectiveness with which work moved to the home highlights the advances in digital technology over the past 10 years. Lest we forget, a mere decade ago, the solitary mass-market home digital device in advanced markets was a PC. The smartphone was, back in 2010, still an exclusive product, owned by a minority of consumers, and connected to 3G networks. Home broadband networks were configured to connect only a handful of devices, preferably via cable.

In 2020, in contrast, most homes in developed markets are connected at super-fast broadband speeds of over 30 megabits per second (Mbps). Indeed, around the world, hundreds of millions of homes are now connected directly to fiber. Any fiber-to-the-home (FTTH) or cable connection could theoretically handle 1 gigabit per second (Gbps) or faster. As a fallback, 5G connections can provide download speeds of hundreds of megabits per second—even higher if there are few users per call. Wi-Fi routers are now capable of hundreds of simultaneous connections, even though few homes would require this yet.

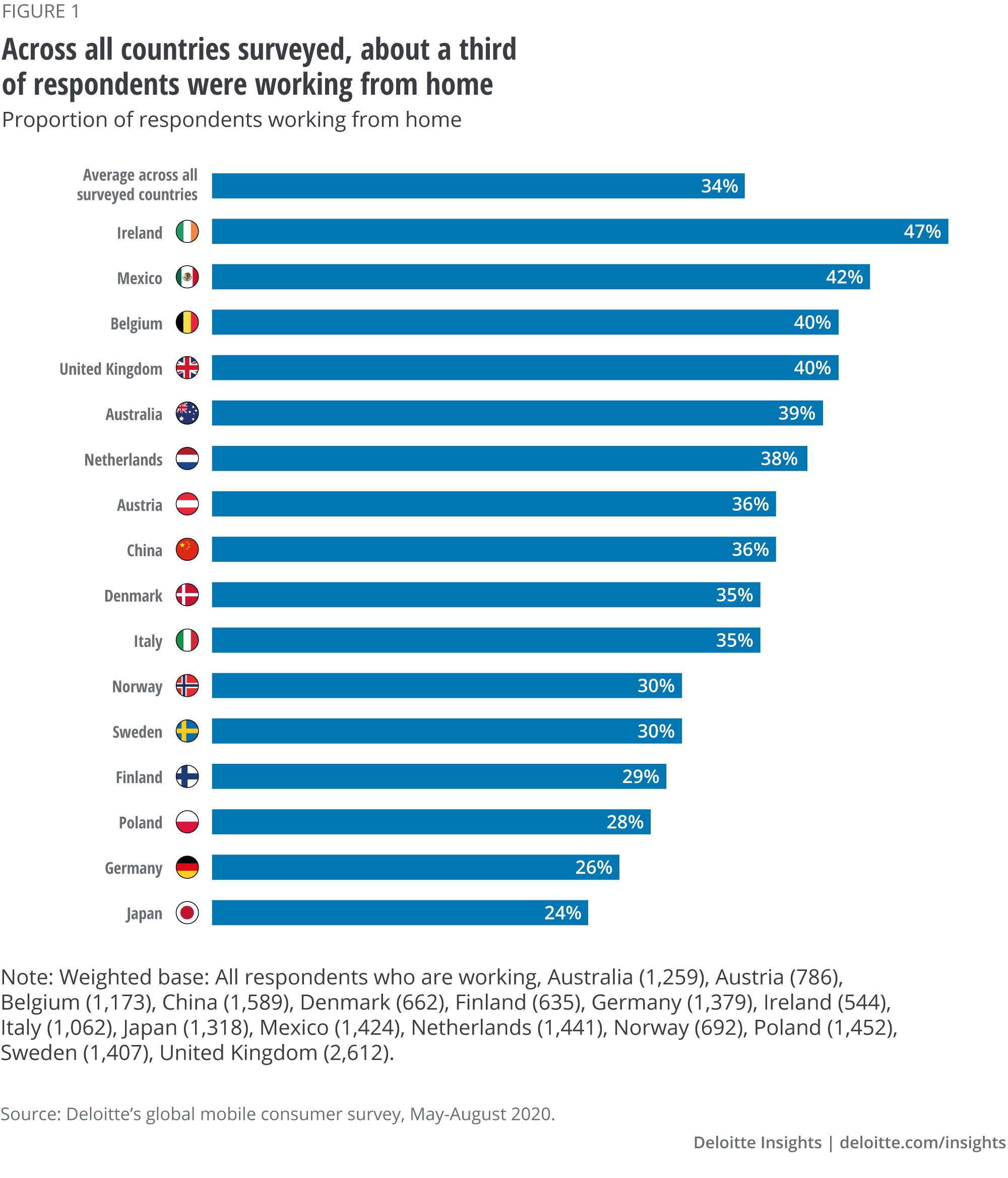

The proportion of the workforce that was able to work at home varied. Across the 16 countries we polled, 34% of workers, on average, were working from home. The highest proportion was in Ireland (47% working from home), followed by Mexico (42%) and the United Kingdom and Belgium (both with 40%) (see figure 1). The lowest proportion of home workers was seen in Japan (24%), Germany (26%), and Poland (28%).

Several factors can explain these variations. One is whether governments and organizations enacted a requirement or strongly encouraged employees to work from home. Japan and Germany never had a full lockdown; office workers were always allowed to work in the office. For example, at the time we surveyed Japan (July and August 2020), workers could work in the office with permission from their employer. In Japan, certain processes also require being in an office, such as the use of traditional seals, known as hanko or inkan, when submitting paper documents.1 Yet the number of COVID-19 cases in Japan and Germany remain some of the lowest per capita in their respective regions.

Another factor is the proportion of each country’s workforce that is able to work remotely. According to one cross-Europe study, 54% of Luxembourg’s workforce is able to function remotely. In Romania, that percentage is 27%.2

The majority of those working at home encountered few technical issues. Only about a third of those polled (33%) encountered at least one type of technical failure. Across all markets we surveyed, the principal technical issues were:

- Broadband failures, encountered by 12% of respondents. The incidence of these issues varied by country, with Mexico faring worst: 28% of workers reported problems. In Ireland, that proportion was 19%, in Australia, it was 18%, and in Poland, it was 16%. Broadband failures can occur for multiple reasons, only one of which is the speed of the connection to the home. The router may be too old; the household may have chosen a broadband package not suited to the number of users in the home; and households may even have had physical impediments to performance, such as thick walls blocking the connection between the router and the laptop.

- PCs working too slowly or stopping working altogether, noted by 12% of respondents. The ability to obtain an upgraded laptop during the pandemic has been harder than in normal times. Supply has been lower due to factories having to close at a time when demand went up. Technical support functions have also had to work at home in some markets, making large-scale upgrade programs harder to deliver.

- Videoconferencing software frequently dropping, experienced by 10% of respondents. Different video calling applications place different demands on processing power. The video calling systems that grow in usage are likely to be those that have the best balance of performance and processing power drain.

Respondents also experienced challenges that hampered, rather than halted, work. The top three constraints were:

- Screen size of home versus office monitors. Twenty-two percent of respondents missed the larger screens they had in their offices. The ability to purchase monitors for working at home has been constrained by lower supply levels. Some companies may not have permitted workers to expense monitors for home offices on the assumption that they would be absent for just a few weeks.

- Slowness of online systems when working from home, reported by 12% of respondents.

- Lack of familiarity with technology for working at home, reported by 10% of respondents.

While most workers in developed markets today may have the technical capability to work at home, how effective were they when they did so during the pandemic? Between May and August this year, a large proportion (57%) of workers perceived that their efficacy declined when working at home.

One reason for workers’ perception that they were less effective, cited by 26% of respondents, was because it was taking longer to complete tasks. Another reason, cited by 24%, was the inability to talk to colleagues and clients face to face. Even though many workers were able to return to their offices over the summer (albeit under markedly different conditions), offices that mandated social distancing of two meters would prohibit team huddles, generating ideas around a whiteboard, or running roundtables. It may be that, now that workers have experienced such COVID-19-safe offices, they would feel more productive working from home. The case for meeting in person is also likely to become harder when workers consider the opportunity cost of travel time. A half-hour journey each way in today’s currency is equivalent to two online video calls.

Another challenge remote workers faced was the ease, or lack thereof, of working from home. More than a fifth of our respondents (23%) said that they were distracted by others (family or housemates) in their households. Households with two working parents with younger children were particularly affected, with work being fitted around the child or children’s schedules. One in five respondents also lacked a comfortable working space, often a predicament for younger workers in shared apartments. One solution to this would be to rent a larger place, possibly in a suburban or even rural setting (subject to the caliber of broadband connectivity) where cost per square meter would be far lower.

The status of working at home has shifted as a result of COVID-19. It is no longer a fallback; for tens of millions, it has become the default. The focus on physical presenteeism will likely lose its edge if most decision-makers are online and workers become accustomed to interacting with each other virtually. With every month that working at home is encouraged for those who can, behavior can become rewired and assumptions will likely change—potentially leading to a major shift in worldwide work practices.

About Deloitte’s 2020 global mobile consumer survey

Deloitte surveyed workers across 16 countries between May and August 2020, each at different stages of lockdown during the polling period. We surveyed the performance of the underlying technology as well as the mood of the workers. The countries polled included 12 European countries, three countries in Asia, and Mexico. The survey population reflected a nationally representative sample for each country, except for China and Mexico, where the online approach led to a high concentration of urban professionals. These respondents are likely to be relatively high earners within their country. Respondents in most countries were aged 18–75 with the exception of the Netherlands (18–70), Austria and Poland (18–65), and China and Mexico (18–50).

More from the Telecom, media & entertainment collection

-

Welcome to the center office Article4 years ago

-

If we rebuild, will they come back? Article4 years ago

-

Reimagining government’s workforce experience Article4 years ago

-

Returning to work in the future of work Article4 years ago

-

Uncertainty and innovation at speed Article4 years ago

-

A case of acute disruption Article4 years ago