Brazil Much work left to be done

Things are looking up economically in Brazil, but the current recovery is a slow one. Policymakers should keep the reforms coming—easing taxes and investment rules—to help promote fiscal healing and speed Brazil up the growth track.

As fireworks lit up the night sky in Copacabana, ushering in a new decade, Brazil’s policymakers may have felt a sense of achievement over the year that was. After all, economic data trickling in over the past few months has turned a tad positive.1 Inflation is down, enabling Banco Central do Brasil (BCB), to focus on growth. And fiscal reforms, such as the one on pensions, have boosted credibility in financial markets.2

Learn more

Subscribe to receive related content from Deloitte Insights

Download the Deloitte Insights and Dow Jones app

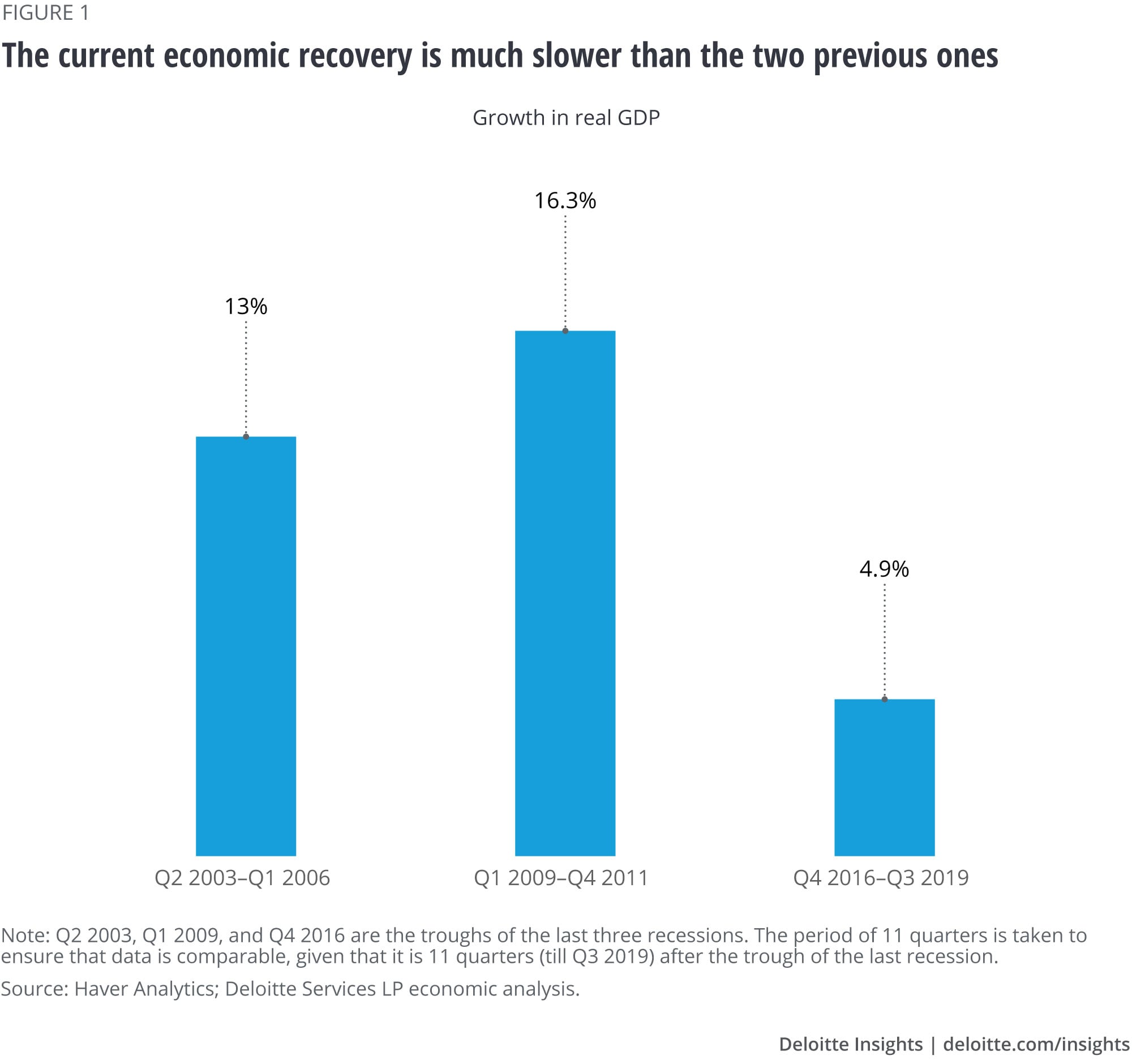

Yet, it could be naïve to think that the fight for the economy is over. In the 11 quarters of economic recovery since Q1 2017, growth in real GDP has been much slower than what it was over similar periods in the two previous recoveries—the ones that started in Q2 2009 and Q3 2003. Private consumption and business investment are yet to pick up speed, weighed down by high unemployment, weak demand growth, and excess capacity. No wonder, then, that both consumer and business confidence are below levels that would denote optimism.3 Policymakers could, therefore, do well to not take their foot off the reforms pedal. Easing the taxation regime and liberalization of trade and investment rules may just be what economists would advise to drive potential economic growth and make Brazil a better place to do business.

Growth picks up, but only slightly

Brazil’s economy grew by 0.6 percent quarter on quarter in Q3 2019, slightly higher than the 0.5 percent rise in the previous quarter (figure 1). Compared to a year ago, the economy grew by 1.2 percent in Q3. Despite the slight uptick in growth, the economy remains fragile—real GDP in Q3 2019 is still about 3.6 percent lower than its peak in Q1 2014. And the current recovery is far slower than previous ones. In the 11 quarters since the trough of the last recession, real GDP has grown by just 4.9 percent, far lower than growth over a similar period in the two previous recoveries (figure 1).

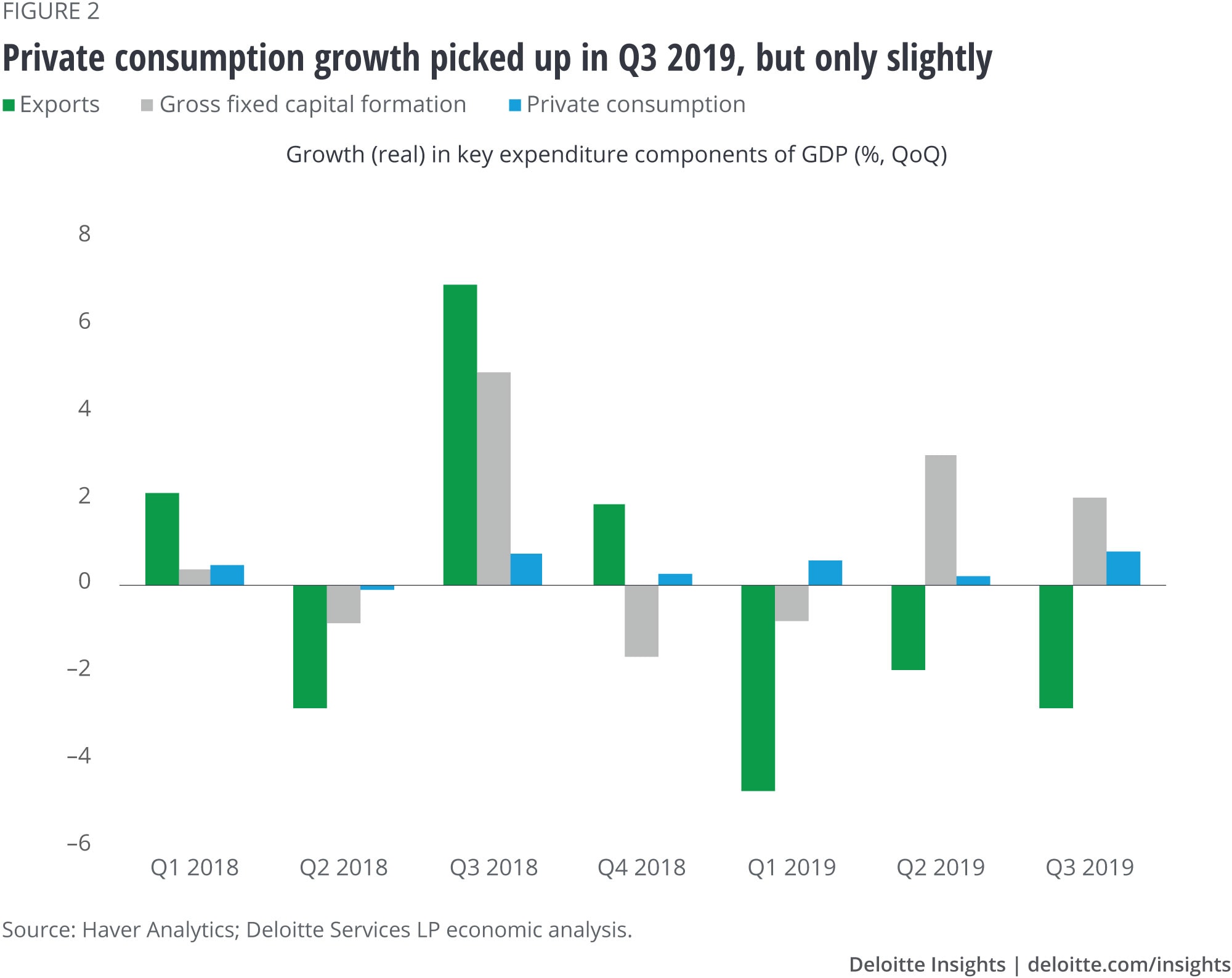

A quick look at the expenditure components of GDP for Q3 2019 reveals that private consumption—a key driver of economic growth—is picking up, albeit slowly (figure 2), as consumers continue to struggle with high unemployment. Consequently, final domestic demand hasn’t picked up enough to kick-start any sharp rise in investments. Gross fixed capital formation, for example, grew by just 2 percent in Q3 2019. Exports continue to weigh on overall growth with the third straight quarter of contraction in Q3, even as government expenditure slows amid the administration’s efforts to mend fiscal health.

Consumer demand is still too weak to induce a sharp investment uptick

Private consumption in Brazil is up against two formidable challenges—a weak labor market and a relatively high debt service ratio. Although unemployment has gone down since 2017, the figure was still high at 11.6 percent (three-month moving average) in October 2019. Adding to unemployment woes is slow real wage growth despite declining inflation. Real average monthly earnings (three-month moving average) went up by 1.5 percent in 2018 and was up just 0.5 percent in the first 10 months of 2019.

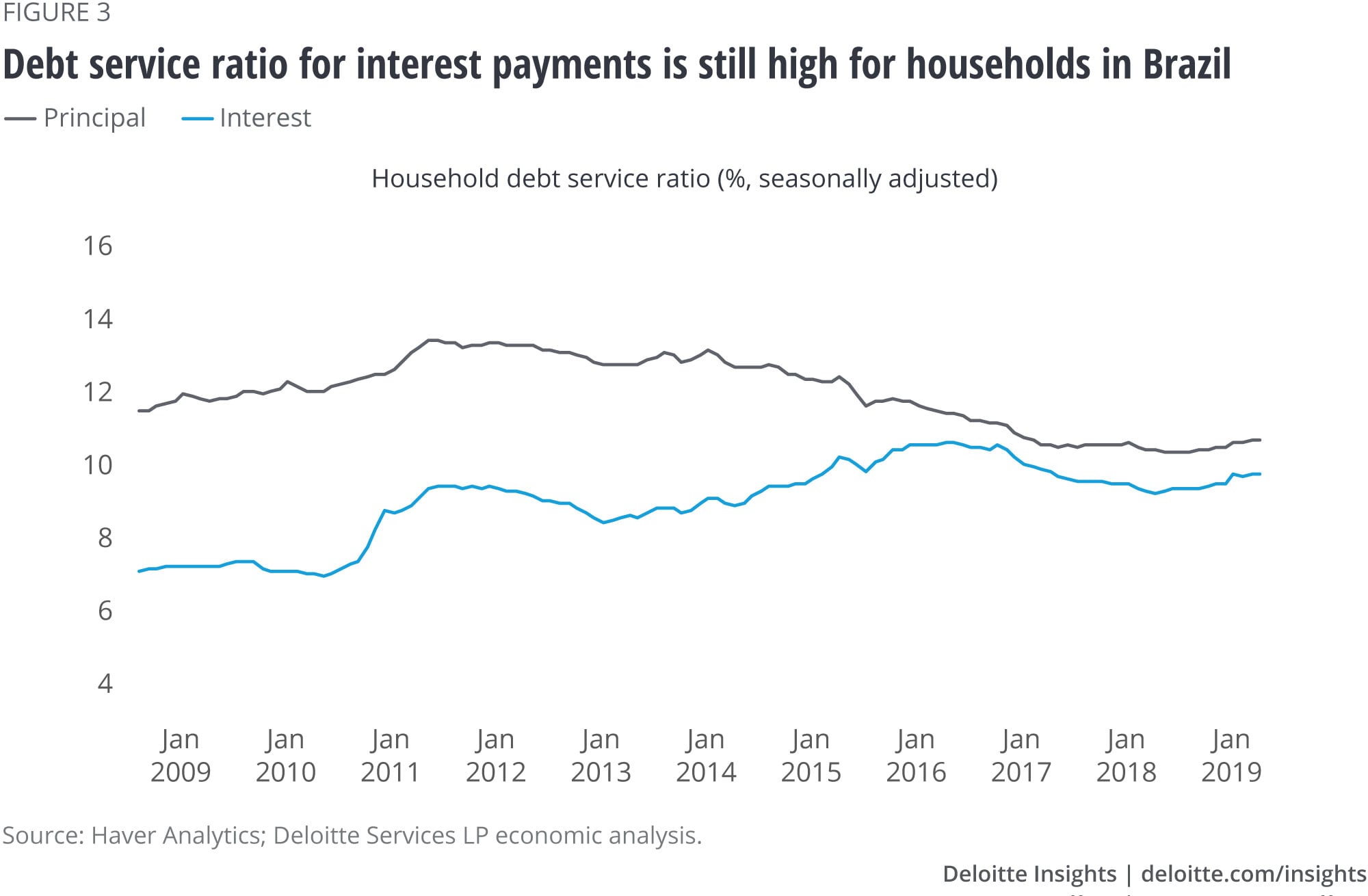

Households are also struggling with debt repayments. Household debt as a share of disposable personal income has started edging up again and debt service ratio, especially on interest payments, is still relatively high (figure 3). As a result, households are likely to direct any gains in income toward partially repaying debt rather than toward spending. With domestic consumption unlikely to pick up sharply in the near term and key neighboring export markets such as Argentina in economic trouble, businesses hardly have any incentive to hike up investment sharply. And that too at a time when there is excess capacity. In October, for example, manufacturing capacity utilization was 78 percent, rising slightly from the low of 2016, but much below the January 2008 peak of 84.6 percent.4

Low inflation is aiding monetary easing

Inflation has been on a broad downward trend since 2016. In November 2019, inflation was 3.3 percent year over year, up from the previous month but below the midpoint of the BCB’s target of 3–6 percent. This was the sixth straight month that headline inflation was below the midpoint of the BCB’s target. Subdued aggregate demand in the economy is weighing on consumer prices, as is evident from low core inflation, a measure that excludes volatile food and energy prices from headline inflation (figure 4). With inflation low, the central bank has been focusing instead on reviving the economy. In December 2019, the BCB cut its Selic rate (policy interest rate) by 50 basis points (bps) for the fourth time this year to 4.5 percent, a record low. Monetary easing in 2019 follows 775 bps worth of rate cuts from October 2016 to March 2018. So far, however, rate cuts haven’t brought about the quantum of demand uptick that some would have hoped for.

With inflation and inflation expectations expected to remain manageable, the BCB is unlikely to reverse monetary policy in 2020. And although declining interest rate differentials with the United States may be a factor impacting the real, Brazil’s currency, the central bank is aware that the dollar’s strength also stems from global economic uncertainties. So, any reversal of monetary policy is unlikely to spruce up the real by much; in contrast, faster growth and reforms will likely aid the currency more.

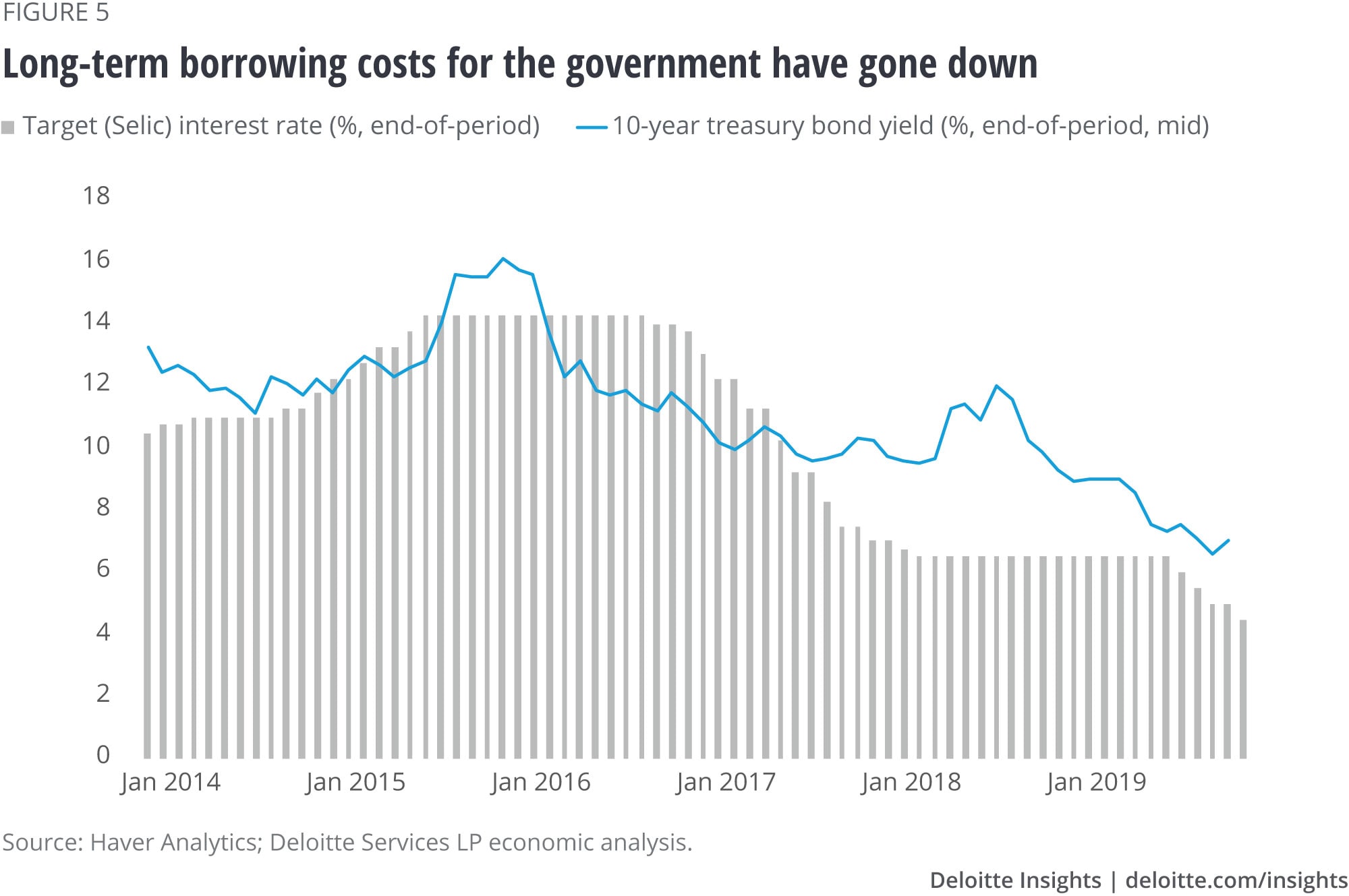

What low policy rates along with key fiscal reforms have achieved is to lower long-term borrowing costs (figure 5). This comes as a big relief to the government as it lowers the burden of interest payments on government debt. And it comes at the right time, as the government is trying to get its fiscal house in order.

Keep the reforms coming

The current economic recovery in Brazil is a slow one. While monetary easing and key fiscal reforms have brought back some confidence in the economy, any strong uptick in economic growth will likely depend on further fiscal healing and reforms. Yet, the path to more reforms—especially those aimed at easing Brazil’s taxation system and liberalizing the domestic market for foreign trade and investments—will not be an easy one. With local elections scheduled for October 2020, the appetite to take seemingly harsh measures may slowly ebb as the days pass. Without these bold measures, however, the economy’s potential will likely remain subdued. And with that, any hope for Brazil to move from tepid economic expansion to a higher growth trajectory will likely fizzle out.

Explore the Economics collection

-

A view from London Article5 days ago

-

What to expect when you’re expecting … a recession Article4 years ago

-

Rising corporate debt: Should we worry? Article5 years ago

-

All in a day’s work—and sleep and play: How Americans spend their 24 hours Article5 years ago

-

Volatility in emerging economies: Is contagion too harsh a word? Article6 years ago

-

How the financial crisis reshaped the world’s workforce Article5 years ago