United States Economic Forecast 3rd Quarter 2019

21 minute read

17 September 2019

Summer policy shifts—along with Fed moves, unpredictable trade announcements, shaky markets, and an ongoing trade war—mean an updated US economic forecast for the coming months.

Introduction: No vacations for policymakers

Washington economic policymakers seem to have put off their vacations this summer. July and August saw three major policy moves, with offsetting impacts on the economic outlook. Any of the three would require a major revision to the forecast, so it should be no surprise that our current forecast looks a bit different than our last forecast, published in May. And of course, unexpected policy changes have made financial markets more volatile.

Learn more

Subscribe to receive the related content from Deloitte Insights

Download the Deloitte Insights and Dow Jones app

Here’s what policymakers were up to instead of relaxing on the beach or hiking in the mountains.

- The Fed decided to lower rates by a quarter point at the July FOMC meeting. After the meeting, Fed chair Jerome Powell tried to limit the interpretations of the change by calling it a “mid-course correction.” That didn’t satisfy traders in short-term government debt, who are now pricing in additional Fed cuts. Further cuts might not have been FOMC members’ intention, but markets are evidently going to continue pressuring the Fed despite the fact that job growth and retail sales remain strong—and that the current slowing in areas such as manufacturing likely partially reflects a return to “normal” after a period of growth supercharged by tax cuts and spending increases.

- Congress agreed on a budget resolution, along with a hike in the debt ceiling, for two years. In theory, this could alleviate major budget challenges until after the next presidential election. In practice, the budget resolution (which sets targets for overall spending) does not mean that appropriations bills (which provide for spending by program and budget line) will easily pass. Last year’s government shutdown happened despite a previous agreement on the year’s overall budget targets.

- The trade war heated up. And it’s now officially a trade war, at least according to the Wall Street Journal’s panel of forecasters.1The administration’s decision to apply tariffs to remaining Chinese goods that were not yet subject to tariffs was answered by an initial depreciation of the yuan, which was answered by the United States declaring China a currency manipulator. A further US tariff hike was met with a Chinese tariff hike. And so on. As even administration insiders acknowledge, the series of tit-for-tat actions leaves both countries worse off in the short run.2Each country is assuming that the pain it is inflicting on the other will be enough to bring a satisfactory resolution to the continuing trade negotiations. At most one country can be correct, and both may end up losing in the long run.

That’s a lot of policy uncertainty. No wonder that the VIX index spiked (to 24.6 on August 6) and that the stock market dropped about 5 percent from mid-July to mid-August.3

The volatility of the stock market is one thing; the reaction of the bond market is more troubling. Bond yields have dropped by almost a full percentage point. By mid-August, the 10-year Treasury note was yielding about 1.7 percent. Market talk focused on the yield spread, but the more concerning question is whether (and why) long-term yields are so low—and whether the United States could follow other countries such as Germany and Japan and experience negative long-term rates.

Our forecast assumes that Congress completes appropriations bills on time. Since the budget agreement removes the budget caps we had previously assumed would become effective starting October 1, this amounts to a substantial increase in our GDP forecast for 2020. Indeed, the impact of the budget agreement is to partially offset the impact of the trade war. The war itself is unlikely to affect the trade balance, which is determined by the demand for US assets. It may, however, already be affecting investment spending. The forecast assumes that uncertainty over trade policy has an increasingly large impact on investment for the next year or two. That will keep growth below potential in 2020, leading job growth to slow and the unemployment rate to rise a bit.

The forecast assumes a very different path for long-term interest rates than our previous forecasts. Instead of assuming that the 10-year Treasury note yield would move back to “normal” (meaning 4.5–5 percent), we are now assuming that the global capital surplus has created a new normal of around 3 percent. Even that may be high—but economists have little to guide us about the “new normal.” The risk that US long-term rates might go negative is now real, if still a bit remote.

While the US economy seems to be continuing its record expansion, growth is slowing in the rest of the world. Some of the major countries in Europe may already be in recession, and China’s growth slowdown is likely to continue. That doesn’t automatically mean the US economy will slump to the same degree. But we continue to believe that the economy is unusually sensitive to shocks that would cause a recession.

The picture of slowing growth and loosening traction of monetary policy means that authorities—hampered by rising budget deficits—might have trouble responding to a crisis. One much-discussed sign of trouble is the inversion of the yield curve. Lacking any good theory to explain why a yield curve inversion leads to a recession, our forecast does not assume a recession in the baseline. But we continue to judge that the probability of a recession is relatively high (25 percent).

Scenarios

Our scenarios are designed to demonstrate the different paths down which the Trump administration’s policies and congressional action might take the American economy. Foreign risks are, if anything, rising, and we’ve incorporated them into the scenarios. But for now, we view the greatest uncertainty in the US economy to be that generated within the nation’s borders.

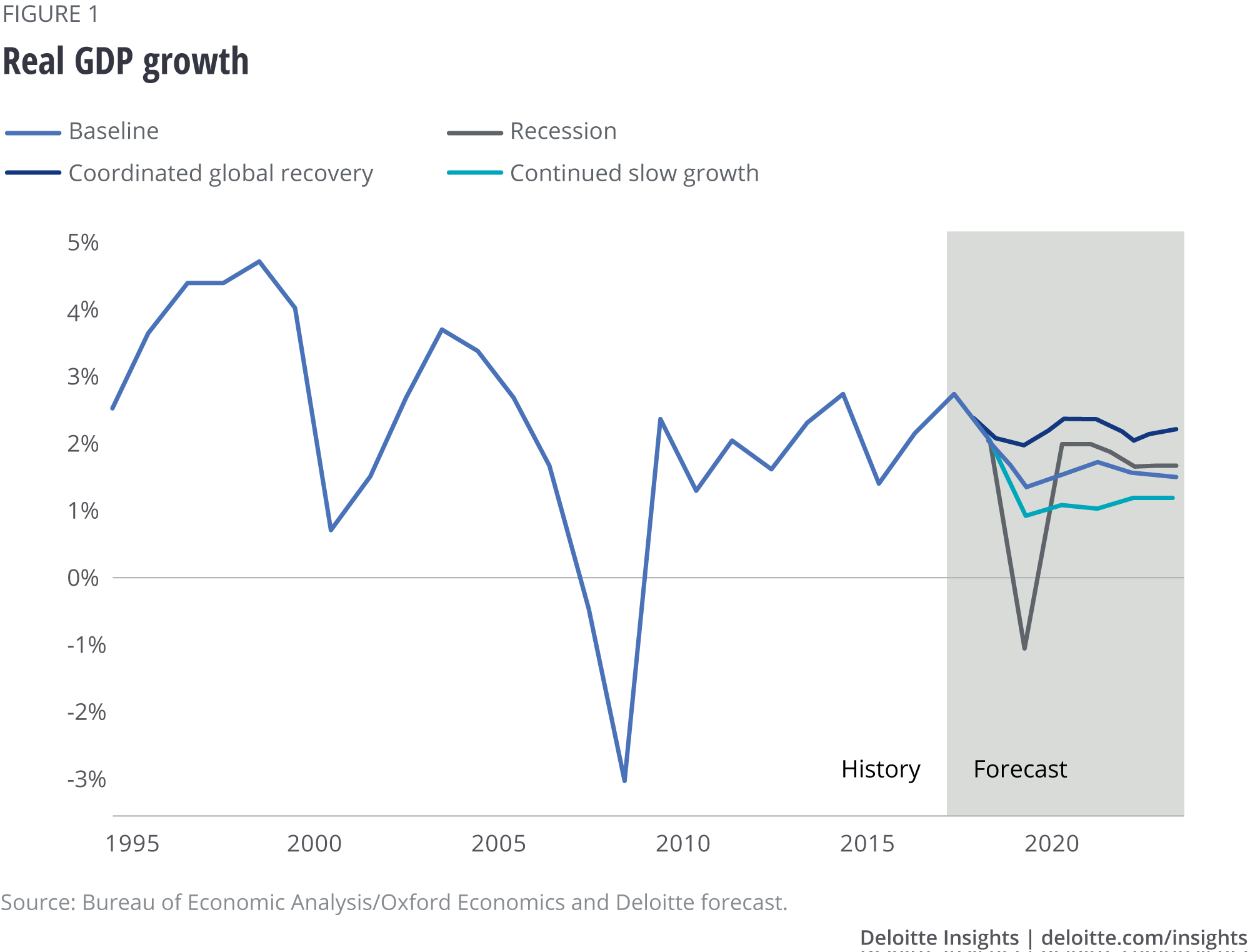

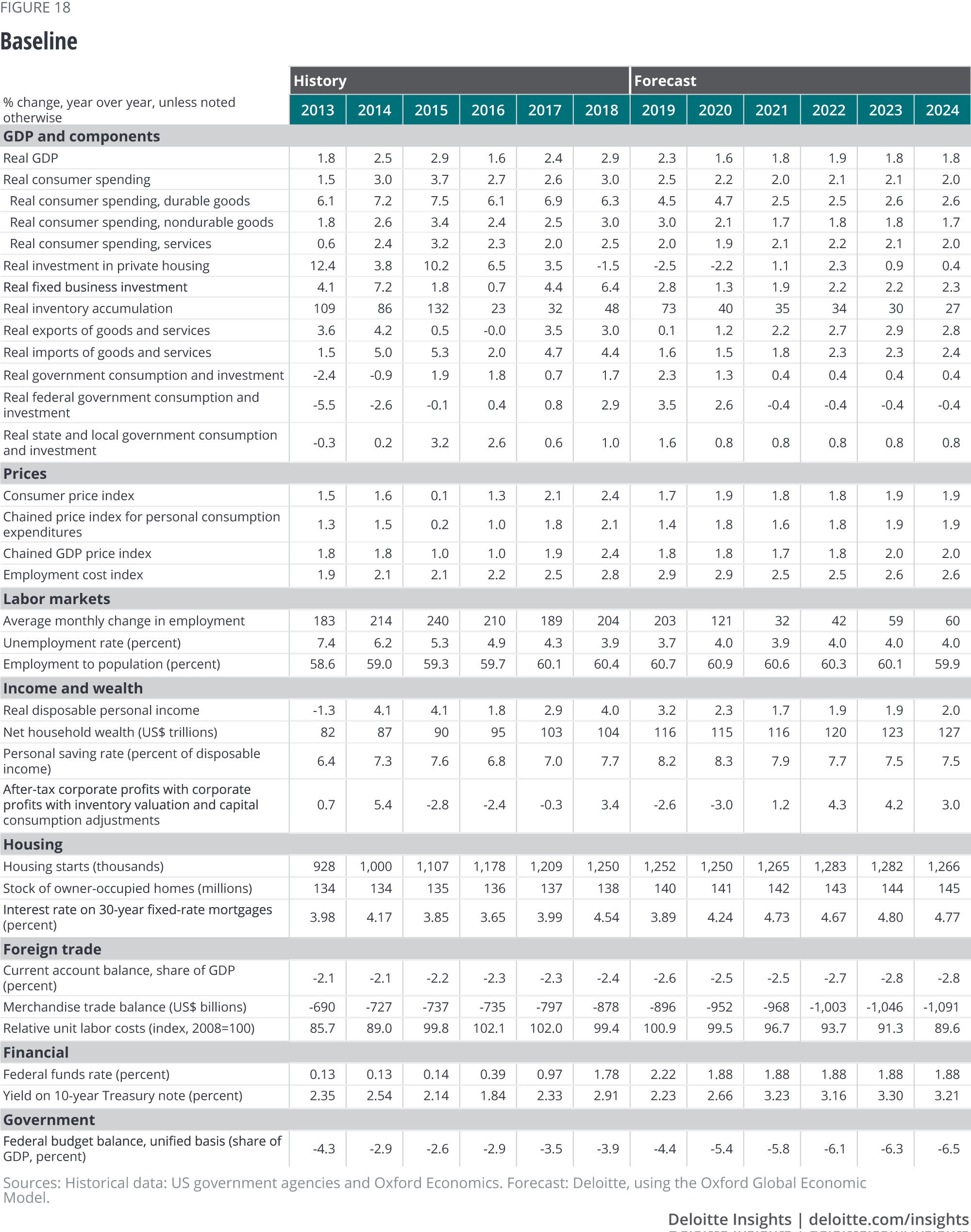

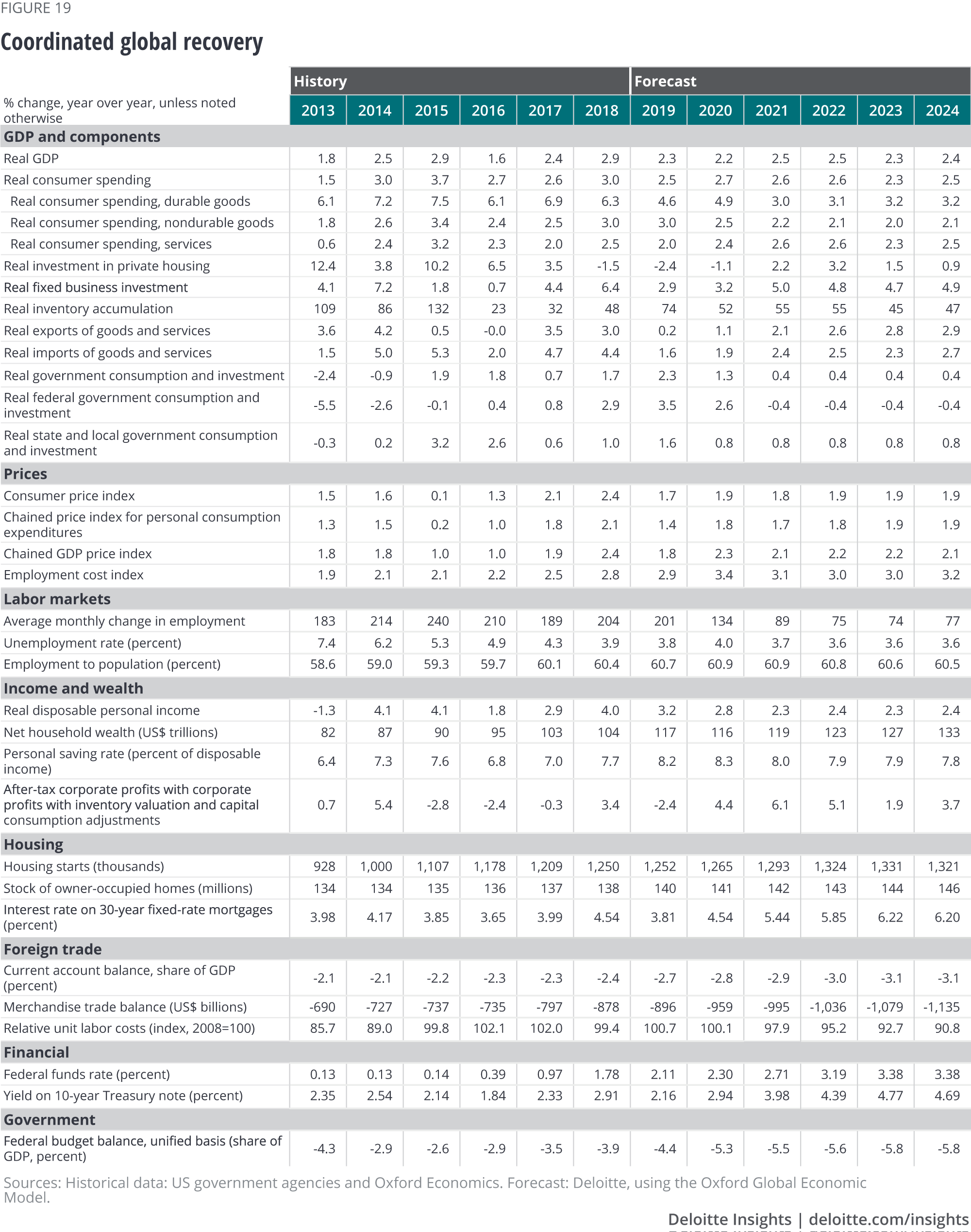

The baseline (55 percent probability): Uncertainty from the trade war with China dampens investment spending. Employment and consumer spending are slow but remain relatively strong. Employment growth stays above the replacement level for another year or two but eventually slows to below 100,000 per month as the stock of potential workers is exhausted. While government spending does not fall, it no longer contributes to accelerating growth. Growth slows below potential in 2020 but picks up to potential (a bit below 2.0 percent) for the remainder of the forecast.

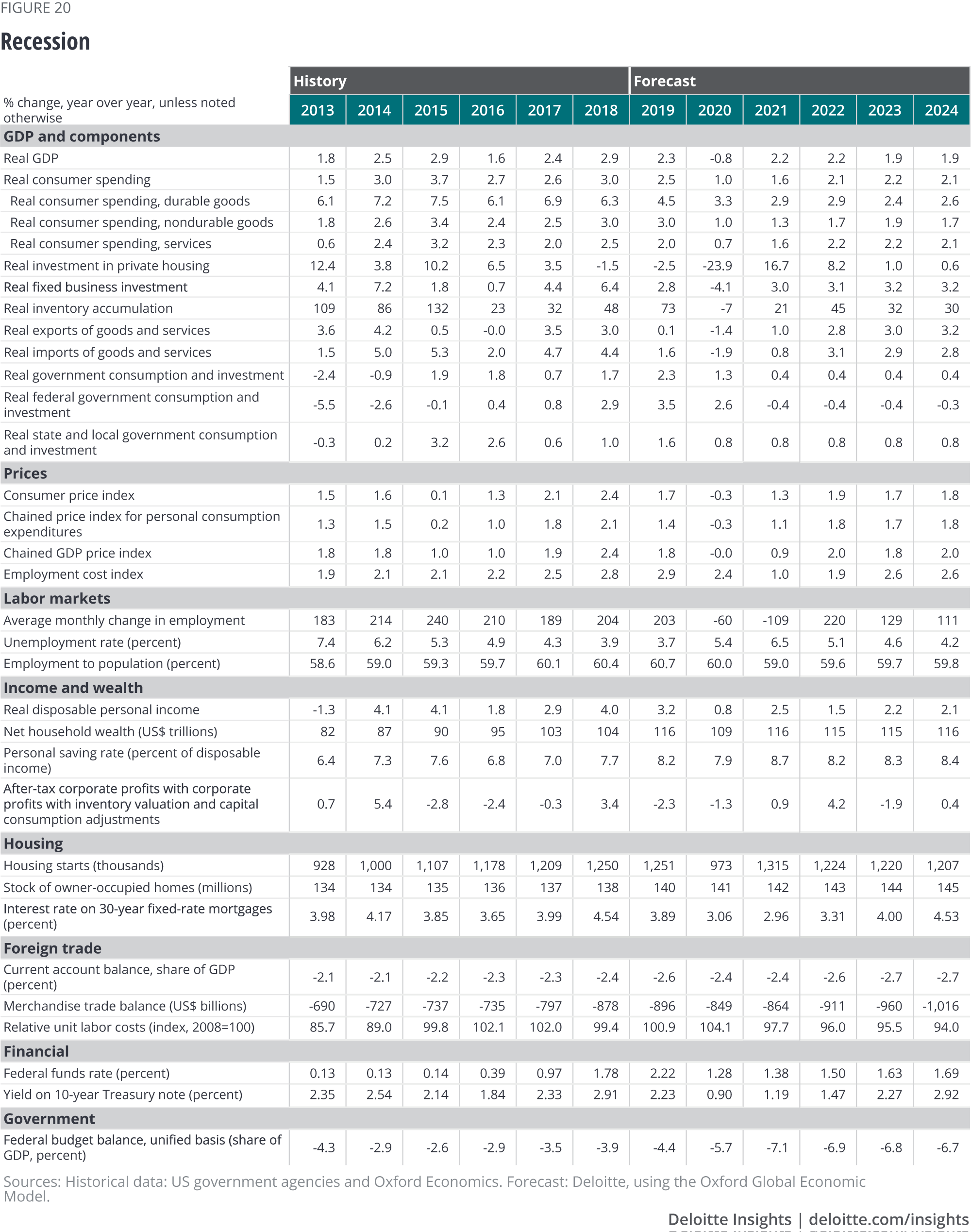

Recession (25 percent): The economy weakens in late 2019 and early 2020 from the impact of tariffs and softening investment spending. With the economy already weak, a financial crisis pushes the economy into recession. The Fed and the European Central Bank act to ease conditions, and the financial system recovers relatively rapidly. GDP falls in the first three quarters of 2020 and then recovers.

Slower growth (10 percent): Productivity growth becomes even more sluggish. Tariffs raise costs and disrupt supply chains. The combination of low returns on investment and uncertainty about trade policy propels businesses to hold back on investments. Foreign growth lowers the demand for US exports. GDP growth falls to less than 1.5 percent over the forecast period, while the unemployment rate rises.

Productivity bonanza (10 percent): Technological advances begin to lower corporate costs, as continuing deregulation improves business confidence. Trade agreements reduce uncertainty. Tariffs are short-lived and turn out to have a smaller impact than many economists expected. Business investment picks up as companies rush to take advantage of the low cost of putting the technology in place. The economy grows 2.5 percent in 2019, with growth at 2.3 percent after 2021, while inflation remains subdued.

Sectors

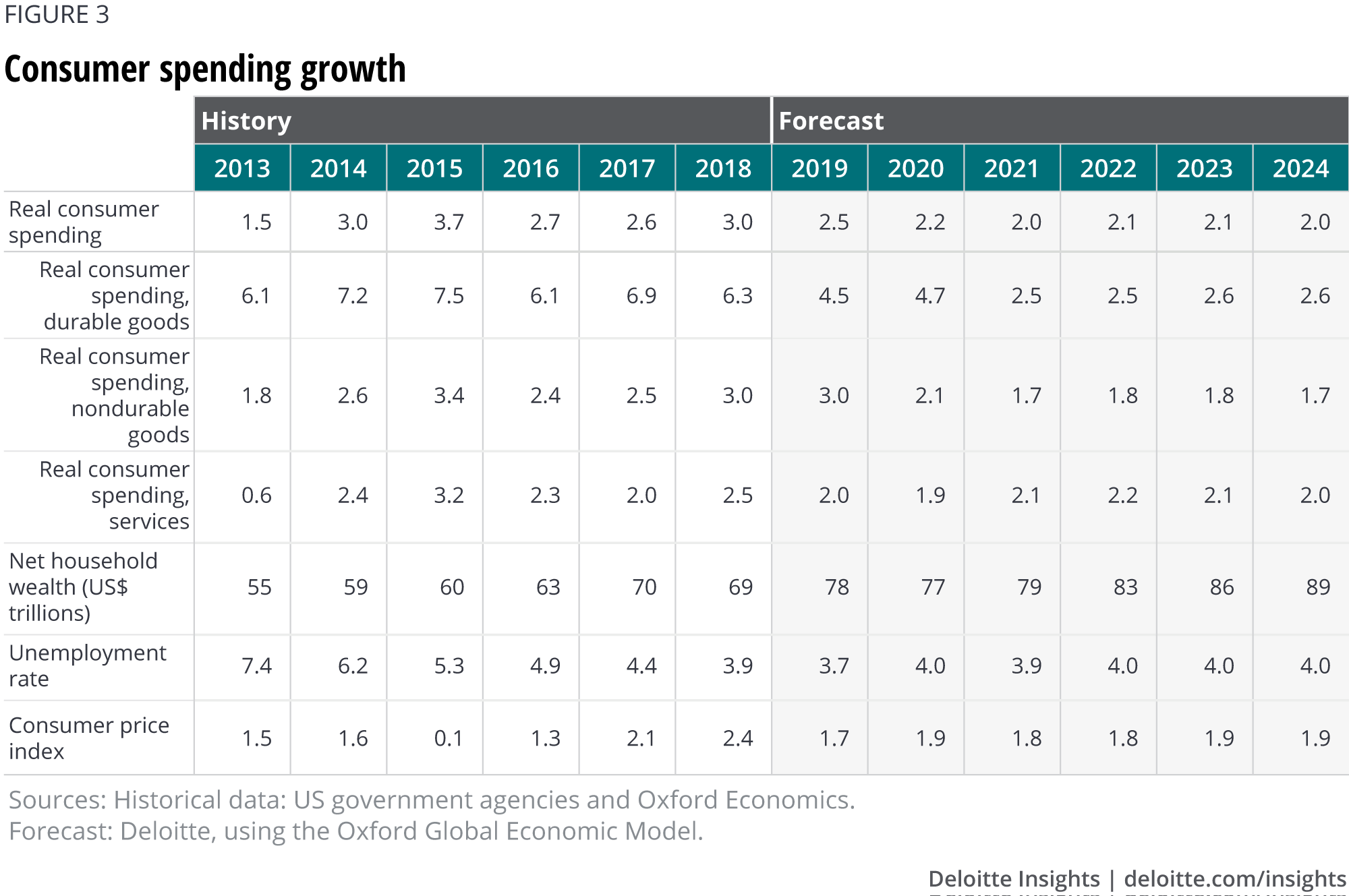

Consumer spending

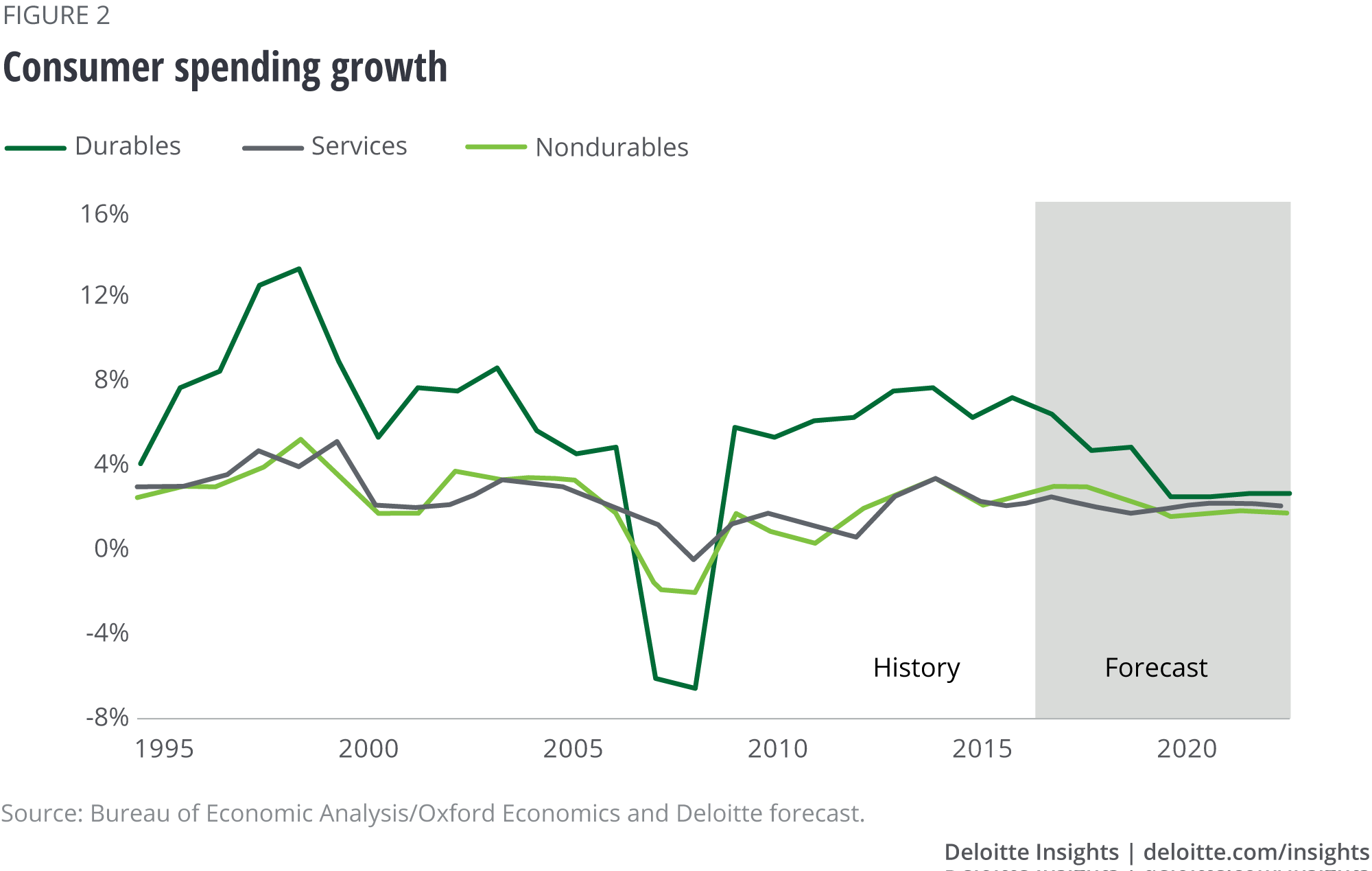

The household sector has provided an underpinning of steady growth for the US economy over the past few years. Consumer spending has grown steadily even as business investment weakened, exports faced substantial headwinds, and housing stalled. But that’s unsurprising, since job growth has remained quite strong. Even with relatively low wage growth, those jobs have helped put money in consumers’ pockets, enabling households to continue to increase their spending. The continued steady (if modest) growth in house prices has helped, too, since houses are most households’ main form of wealth.

For all the daily speculation about how political developments might affect consumer choices when it comes to spending decisions, political noise seems to be just that—in the background—to consumers who seem focused on their own situations. As long as job growth holds up and house prices keep rising, consumer spending will likely remain strong. And the 2017 tax cut, while modest for most consumers, seems to have bolstered their confidence that they can safely spend. At some point, wages might begin to rise enough for people to notice, and that could give consumer spending a further boost.

The medium term presents a different picture. Many American consumers spent the 1990s and ’00s trying to maintain spending even as incomes stagnated. But now they are wiser (and older, which is another challenge, as many baby boomers face imminent retirement with inadequate savings4). That may constrain spending and require higher savings in the future. And although American households seem to face fewer obstacles in their pursuit of the good life than just a few years ago, rising income inequality could pose a significant challenge for the sector’s long-run health. For instance, low unemployment hasn’t alleviated many people’s economic insecurity: Four in 10 adults would be able to cover an unexpected US$400 expense only by borrowing money or selling something.5 For more about inequality, see Income inequality in the United States: What do we know and what does it mean?6

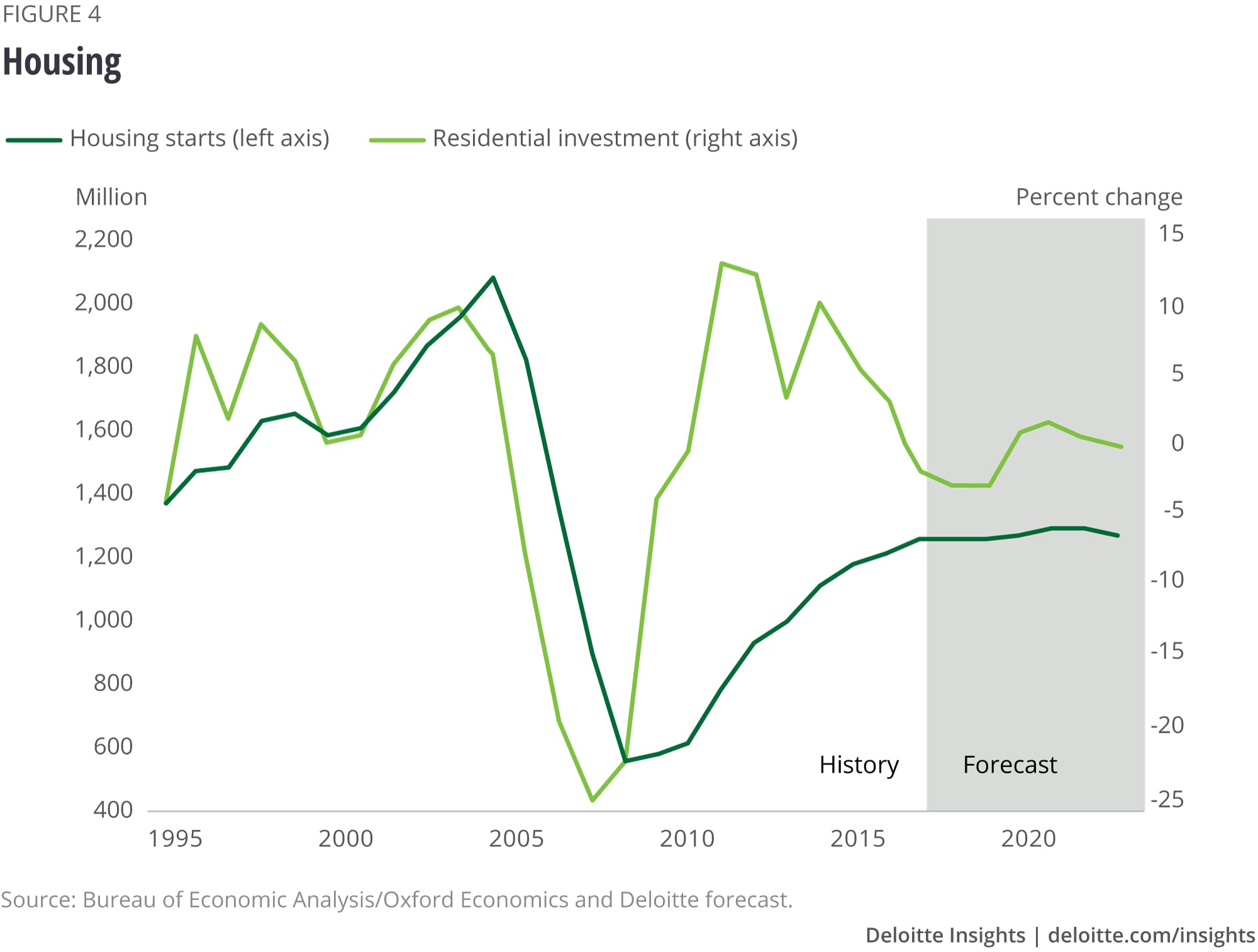

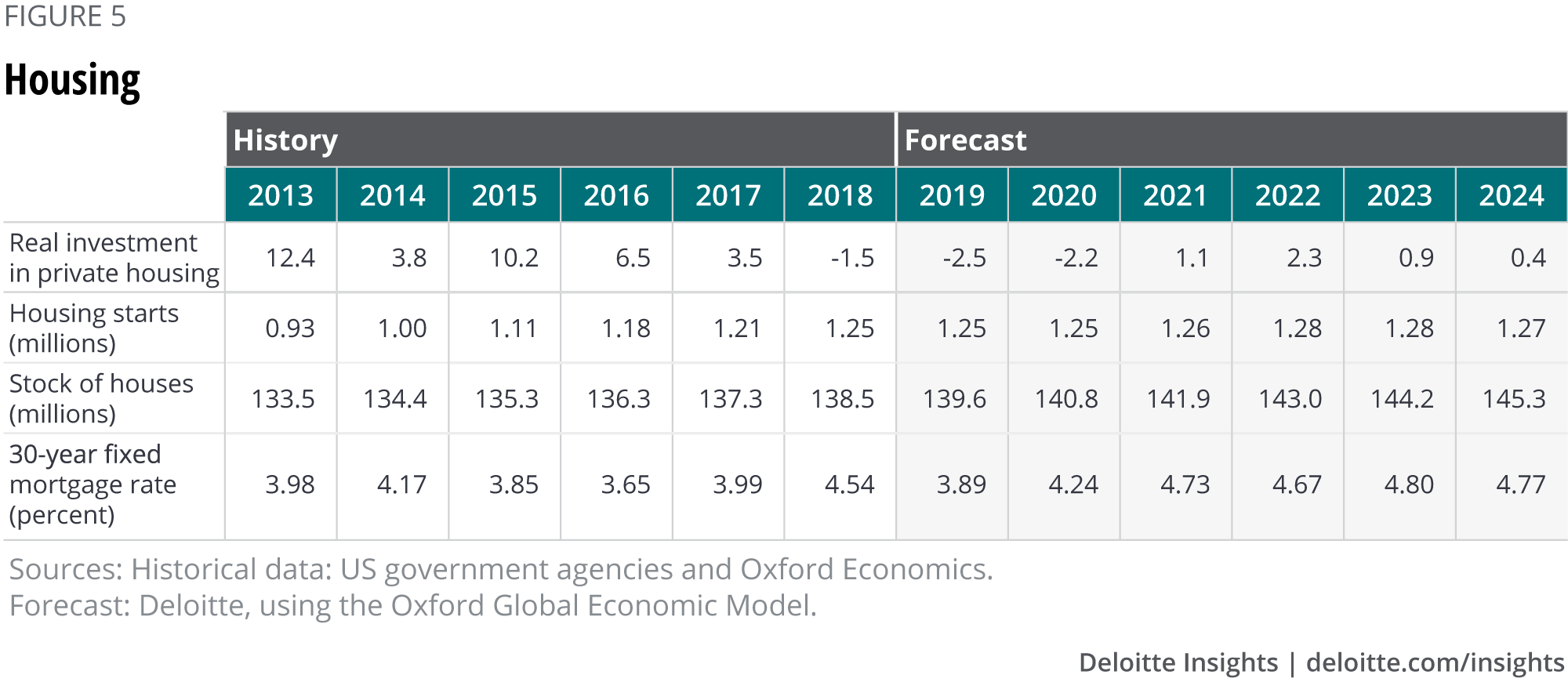

Housing

The housing market has weakened. In fact, we might have seen the best of the recovery from the sector’s destruction in the 2007–09 crash. Housing starts at the current level of around 1.2 to 1.3 million may be able to meet the needs of the population, limiting the upside to the sector. We created a simple model of the market based on demographics and reasonable assumptions about the depreciation of the housing stock;7 it suggests that housing starts are likely to stay in the 1.1–1.2 million range. Starts are likely to fall as the economy weakens in the next year or two, and then gradually increase over the five-year horizon. Housing remains a smaller share of the economy than it was before the Great Recession, and that’s to be expected. In some ways, it’s a relief to see the sector return to “normalcy.” But with slowing population growth, housing simply can’t be a major generator of growth for the US economy in the medium and long run.

Some folks are reacting to the slowing housing market with alarm, remembering something about how the last recession was connected to a housing problem.8 It’s certainly not a happy sight, especially for anybody in the home construction business. But a construction decline didn’t cause the last recession: Construction began subtracting from GDP growth in the fourth quarter of 2005, two years before the recession, and GDP growth remained healthy. It was housing finance that ultimately created the crisis, not housing itself. Today, housing accounts for just under 4.0 percent of GDP, down from about 6.0 percent in 2005. The sector simply isn’t large enough to cause a recession—unless, once again, huge hidden bets on housing prices come to light.

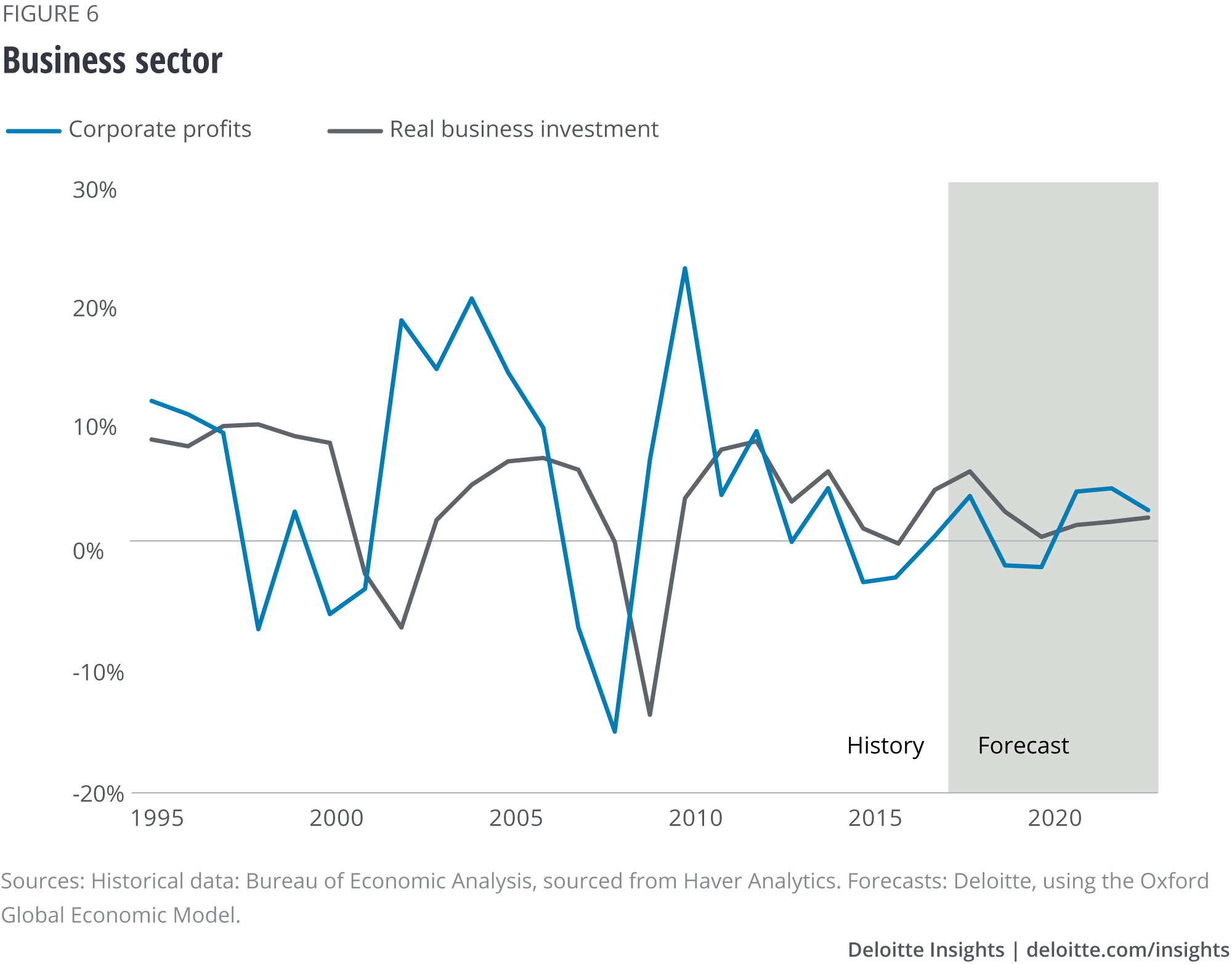

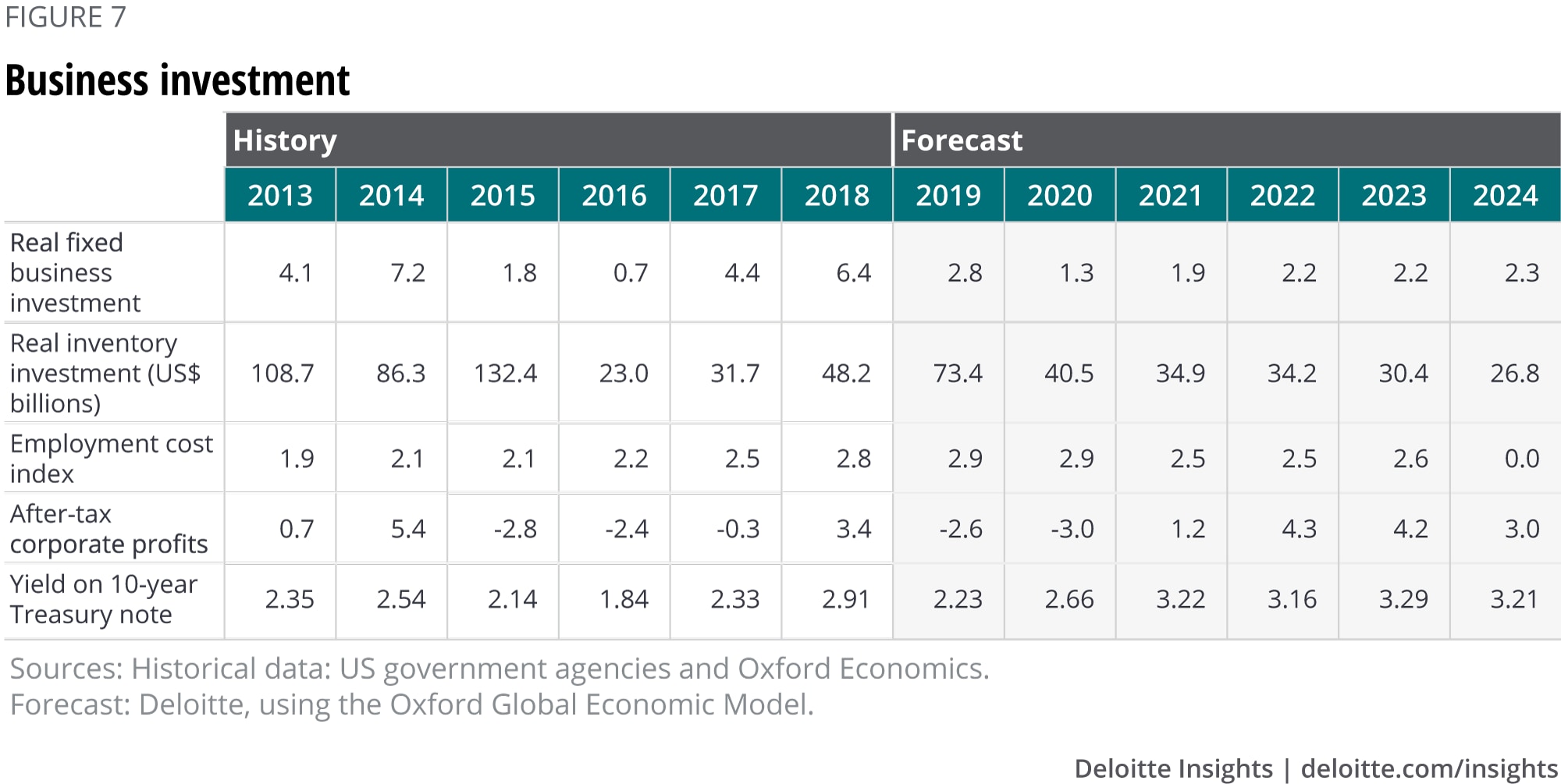

Business investment

While businesses were still reckoning with the implications of the tax bill for investment, the US government introduced additional uncertainty with a significant shift in international trade policy.9 And while passage of the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2019 answered some budget questions, plenty of uncertainty remains. On top of everything else, the Fed has executed a 180-degree turn in policy over the past six months, leaving Fed watchers arguing about what might happen next. Policy uncer tainty is one of the biggest potential roadblocks to strong investment spending.

Business investment has been slowing in the past few quarters despite a decline in long-term interest rates and the reduced tax rate on corporate profits. In truth, the cost of capital has been at historic lows over the past decade, but many businesses have remained reluctant to take advantage of cheap capital to raise investment. Nothing that has happened in the past few years seems to have substantially altered that problem, and many analysts are skeptical that further rate cuts would spur new investment.

The imposition of tariffs on a wide variety of goods—and foreign retaliation in the form of tariffs on American products—creates even more uncertainty, particularly for manufacturing firms. Some CEOs face a painful medium-term dilemma: deciding whether their businesses need to rebuild their supply chains. Industries such as automobile production have developed intricate networks across North America and are reaching into Asia and Europe, based on the longstanding assumption that materials and parts can be moved across borders with little cost or disruption.

And fiscal policy uncertainty lingers. While the budget bill took the debt ceiling off the table for two years, Congress must still pass appropriations bills before the end of the fiscal year. Policy uncertainty is therefore likely to continue to weigh on investment decisions.

The Deloitte economics team remains optimistic about investment in the medium term, since the United States remains a fundamentally good place to do business. But business investment plays a key role in differentiating between Deloitte’s baseline, slow growth, and productivity bonanza scenarios. One marker of the difference between the scenarios is productivity. If it accelerates enough, businesses might be persuaded to up their investment, which is what happens in the productivity bonanza scenario. But decelerating productivity could leave businesses unwilling to spend more money to put new capital in place, further slowing the economy, as in the slower growth scenario.

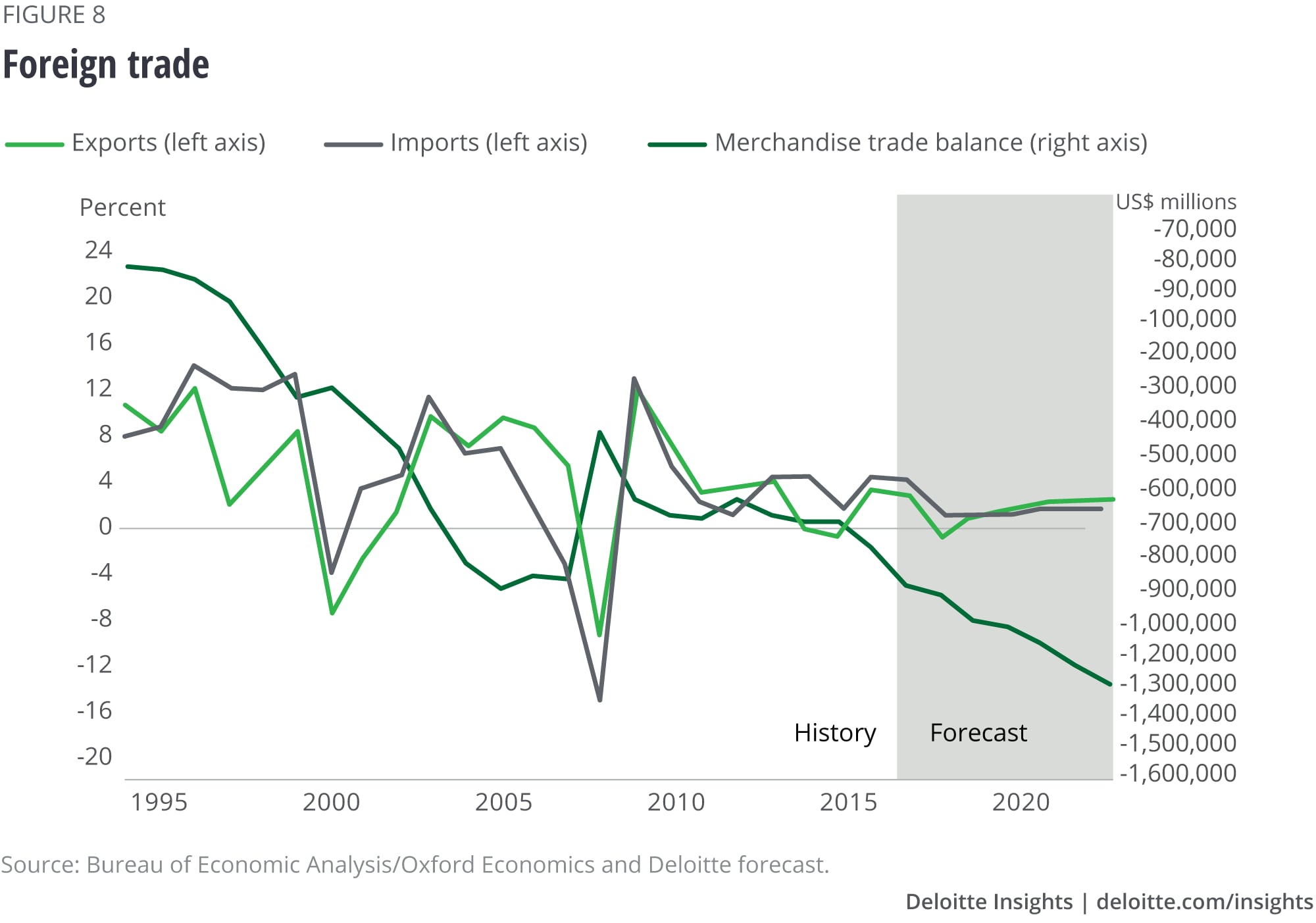

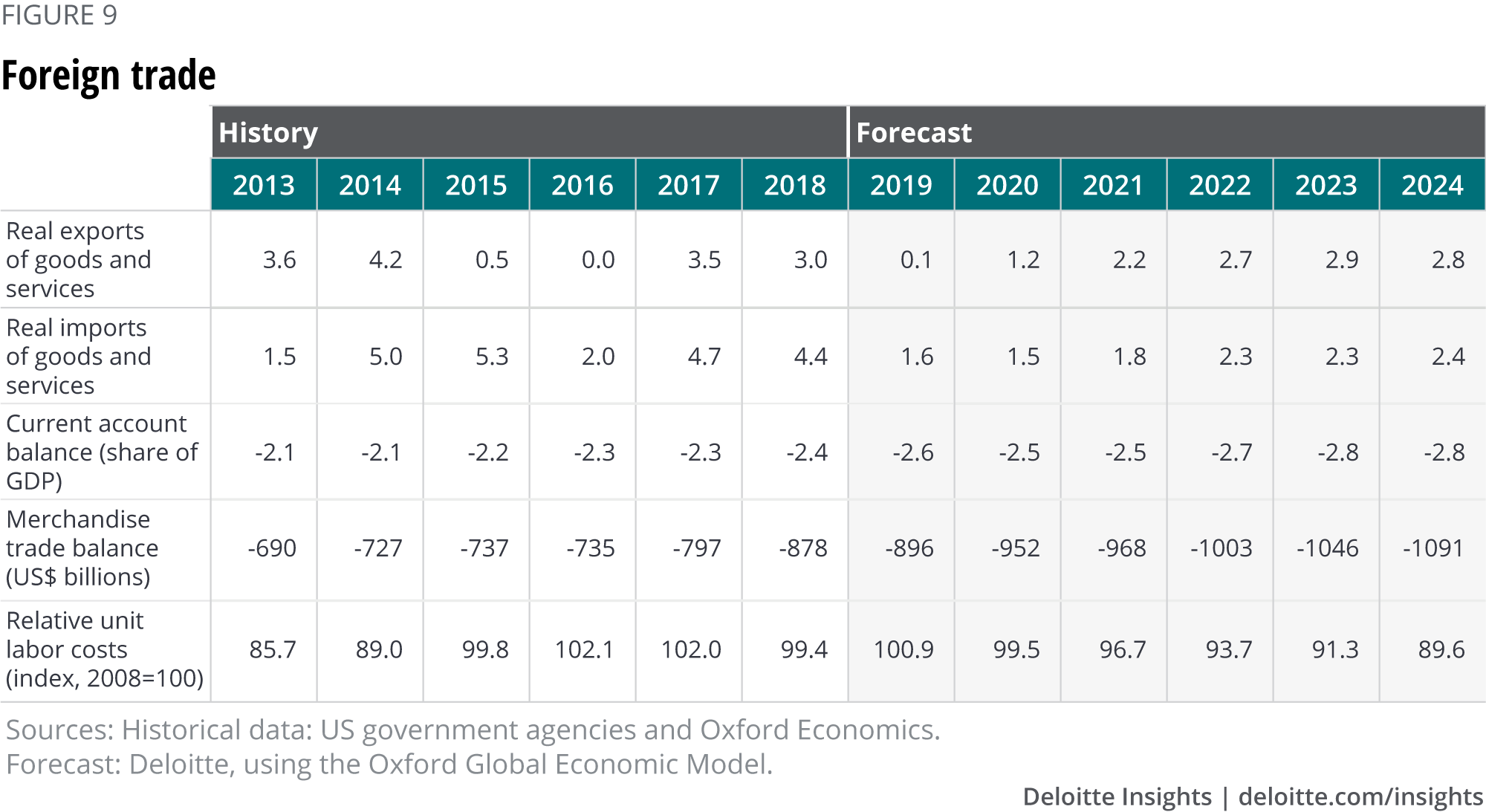

Foreign trade

Over the past few decades, business—especially manufacturing—has taken advantage of generally open borders and cheap transportation to cut costs and improve global efficiency. The result is a complex matrix of production that makes the traditional measures of imports and exports somewhat misleading. For example, in 2017, 37 percent of Mexico’s exports to the United States consisted of intermediate inputs purchased from . . . the United States.10

Recent events appear to be placing this global manufacturing system at risk. The United Kingdom’s increasingly tenuous post-Brexit position in the European manufacturing ecosystem,11 along with ongoing negotiations to replace the North American Free Trade Agreement, may slow the growth of this system or even cause it to unwind.

But the biggest challenge now facing the global trading system is the unpredictable tit-for-tat explosion of trade restrictions between China and the United States.

The trade war flared up this summer when President Trump announced that the United States would impose a 10 percent tariff on all Chinese goods not already affected by tariffs on September 1.12 China responded by permitting its currency to depreciate by about 2 percent; the administration countered by making an official declaration that China is a “currency manipulator.”13 By mid-August, the administration had delayed some (but not all) of those tariffs.

The real issue is the uncertainty about the tariffs and the US government’s goals in imposing these taxes. White House trade adviser Peter Navarro argues that the tariffs are necessary to reduce the US trade deficit and to help the United States strengthen domestic industries such as steel production for strategic reasons.14 This suggests that tariffs in “strategic” industries could be permanent. But Commerce Secretary Wilbur Ross has stated that the goal is to force US trading partners to lower their own barriers to American exports.15 That suggests that the administration intends the tariffs to be a temporary measure to be traded for better access to foreign markets.

The apparent lack of clarity in the administration’s stated objectives for tariffs adds to the overall uncertainty about global trade policy. In the short run, uncertainty about border-crossing costs may reduce investment spending. Businesses may be reluctant to invest when facing the possibility of a sudden shift in costs. Deloitte’s baseline scenario assumes that the impact is large enough to affect overall business investment, and the slow scenario assumes a wider trade war and a larger impact on investment.

The challenge that many companies face is that a significant change in border-crossing costs—as would occur if the United States withdrew from NAFTA without adopting its replacement, the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement, or made tariffs on Chinese goods permanent—could potentially reduce the value of capital investment put in place to take advantage of global goods flows. Essentially, the global capital stock could depreciate more quickly than our normal measures would suggest. In practical terms, some US plants and equipment could go idle without the ability to access foreign intermediate products at previously planned prices.

With this loss of productive capacity would come the need to replace it with plants and equipment that would be profitable at the higher border cost. We might expect gross investment to increase once the outline of a new global trading system becomes apparent.

In the longer term, a more protectionist environment is likely to raise costs. That’s a simple conclusion to be drawn from the fact that globalization was largely driven by businesses trying to cut costs. How those extra costs are distributed depends a great deal on economic policy—for example, central banks can attempt to fight the impact of lower globalization on prices (with a resulting period of high unemployment) or to accommodate it (allowing inflation to pick up).

Whatever happens, the tariffs are unlikely to have a direct impact on the US current account, except perhaps in the very short run. The current account is determined by global financial flows, not trade costs.16 Any potential reduction in the current account deficit is likely to be largely offset by a reduction in American competitiveness through higher costs in the United States, lower costs abroad, and a higher dollar. All four scenarios of our forecast assume that the direct impact of trade policy on the current account deficit is small. In fact, despite the impact of a wide variety of tariffs on American imports over the past two years, the US trade deficit has increased substantially, from a seasonally adjusted monthly rate of around US$46 billion in January 2017 to US$55 billion in June 2019. The evidence is clear that the tariffs have not reduced the country’s trade deficit.

Adding to the problems in the trade sector, growth in Europe and China has clearly slowed. These are two of the three regions that drive the global economy (the third is the United States). Slow growth abroad is very likely to translate into slower growth in US exports and perhaps a higher dollar, further slowing export growth. That’s an important contributor to downside risk for the American economy.

Brexit is an immediate issue in the short run, although it does not affect the medium- or long-term US outlook that much. A hard Brexit is unlikely to significantly affect US sales abroad directly. But it could help soften overall European economic growth even further, providing yet another headwind for American exporters.

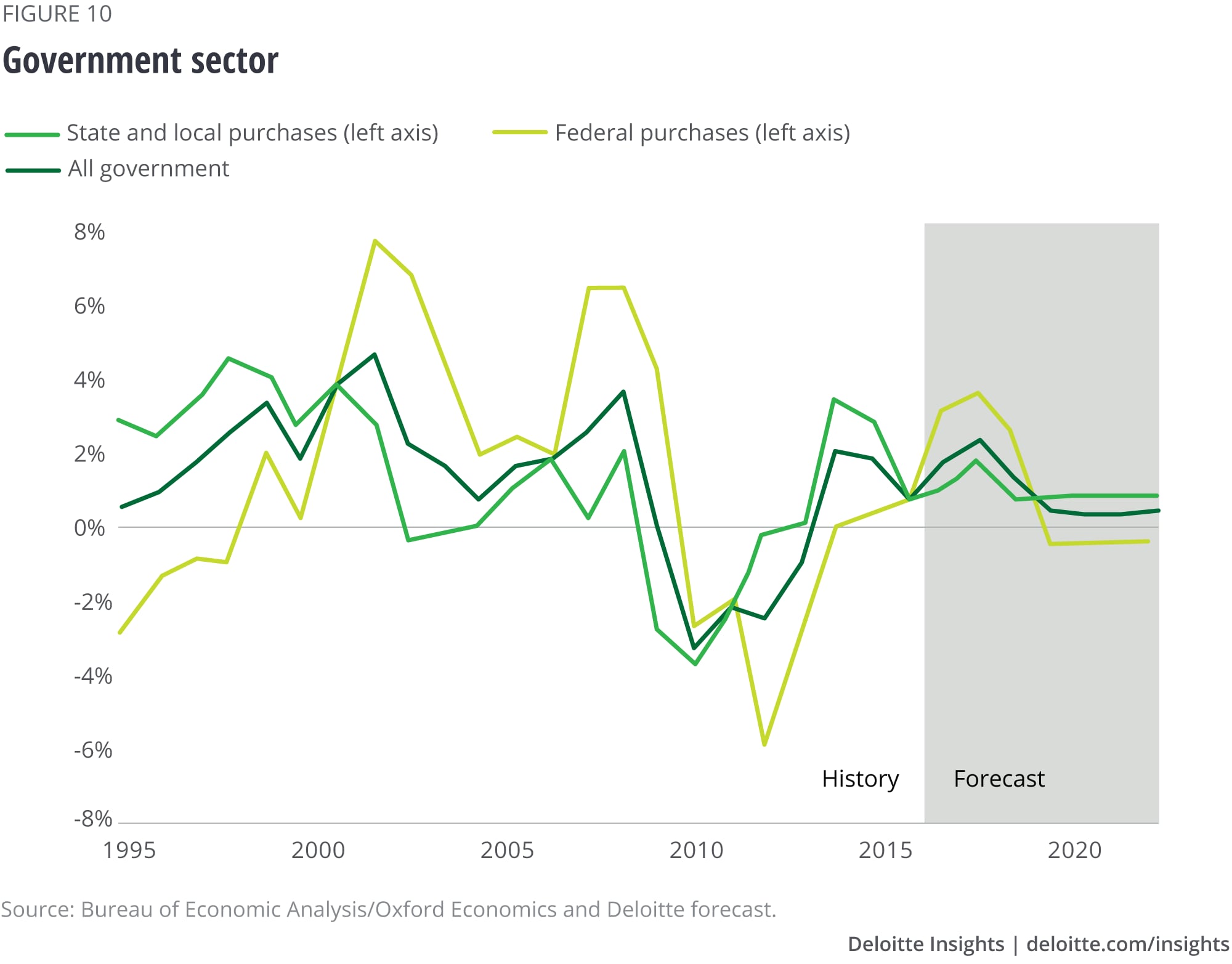

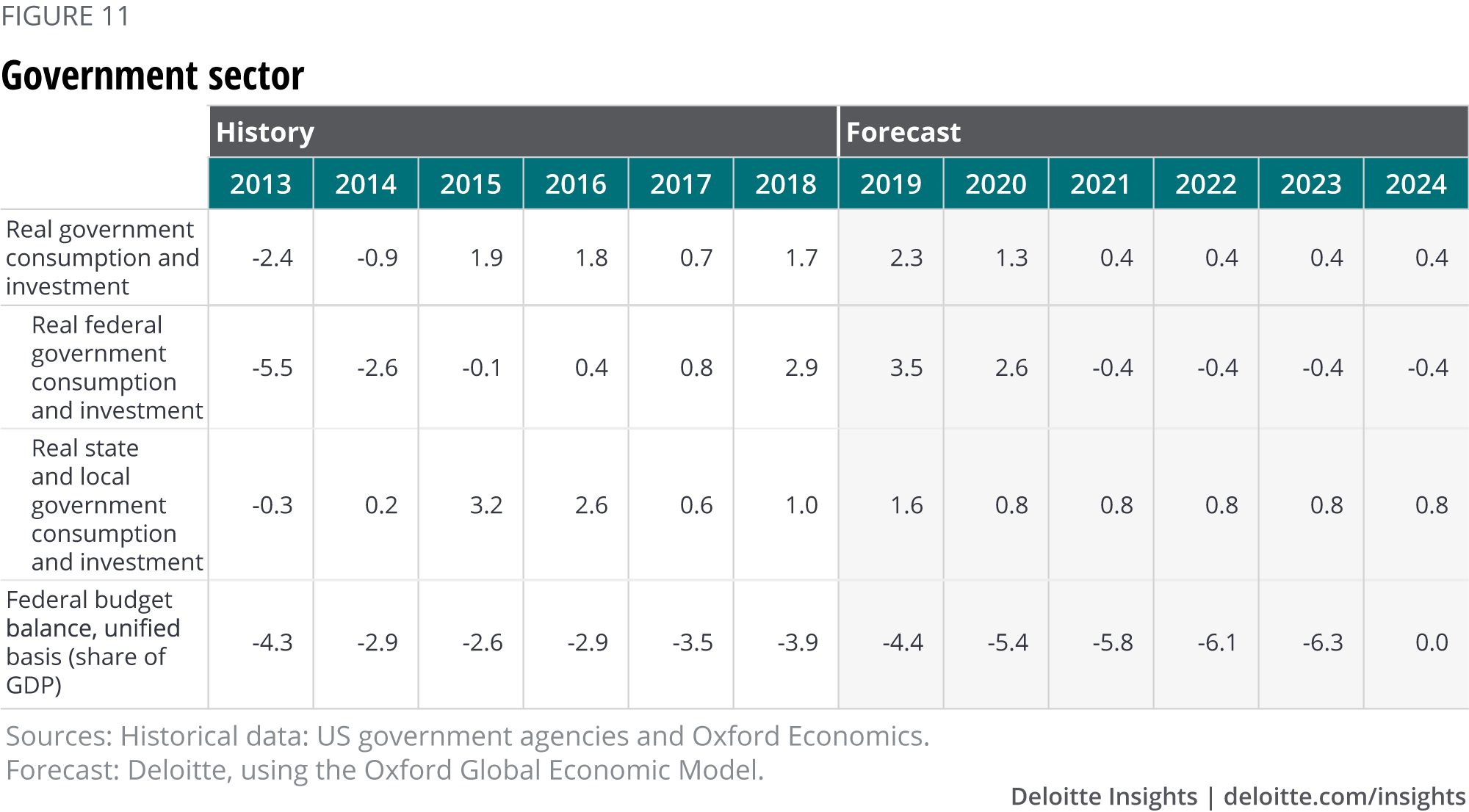

Government

In July, Congress passed, and the president signed, a two-year budget agreement. What’s included: a removal of the debt ceiling (for two years) and total budget amounts for defense and nondefense discretionary spending. What’s not included: all the detailed and specific spending amounts that go into the appropriations bills.

This is generally good news, as it takes a lot of uncertainty off the table. But much remains. The last two-year budget agreement didn’t prevent a government shutdown. The various congressional committees now have a relatively short time to write the 13 appropriations bills and get them passed. And they’ll have to do it again next year. The last shutdown took place because Congress and the president could not agree on spending within previously agreed budget guidelines, and that could happen again. So the possibility of a government shutdown—while lower than in the past—is far from zero.

High government spending doesn’t help the long-term budget outlook, but it does prevent the spending cliff that would have occurred had the budget caps gone back into place. That means that government spending won’t fall, even if it won’t continue to contribute to growth. As a result, we’ve raised our outlook for GDP in 2020 substantially, although it is still relatively low because of the trade dispute with China.

On top of this, the demand-side impact of the 2017 tax cut has long passed. What’s left is not much: The reduction in tax rates simply does not seem to be translating into a significant increase in business investment. Or perhaps the impact of other problems, such as the trade war, has overwhelmed any positive impact of the tax bill. In any event, investment spending has been slowing. We expect that to continue for at least a few quarters because of the uncertainty around trade policy. The supply-side impact of the tax cut remains a matter of debate, with estimates ranging from no real change after a decade (Tax Policy Center) to 2.8 percent, or almost 0.3 percentage points annually (Tax Foundation).17 But the relatively muted response of business investment to the tax cut argues for the lower end of the range.

After years of belt-tightening, many state and local governments are no longer actively cutting spending. However, many state budgets remain constrained by questions around the effects of new federal tax policy18 and the need to meet large unfunded pension obligations,19 so state and local spending growth will likely remain low over this forecast’s five-year horizon.

Pressure is building for increased spending in education, as evidenced by last year’s public teacher protests in several states.20 With education costs accounting for about a third of all state and local spending, a significant upturn in this category could create some additional stimulus—or could require an increase in state and local taxes.

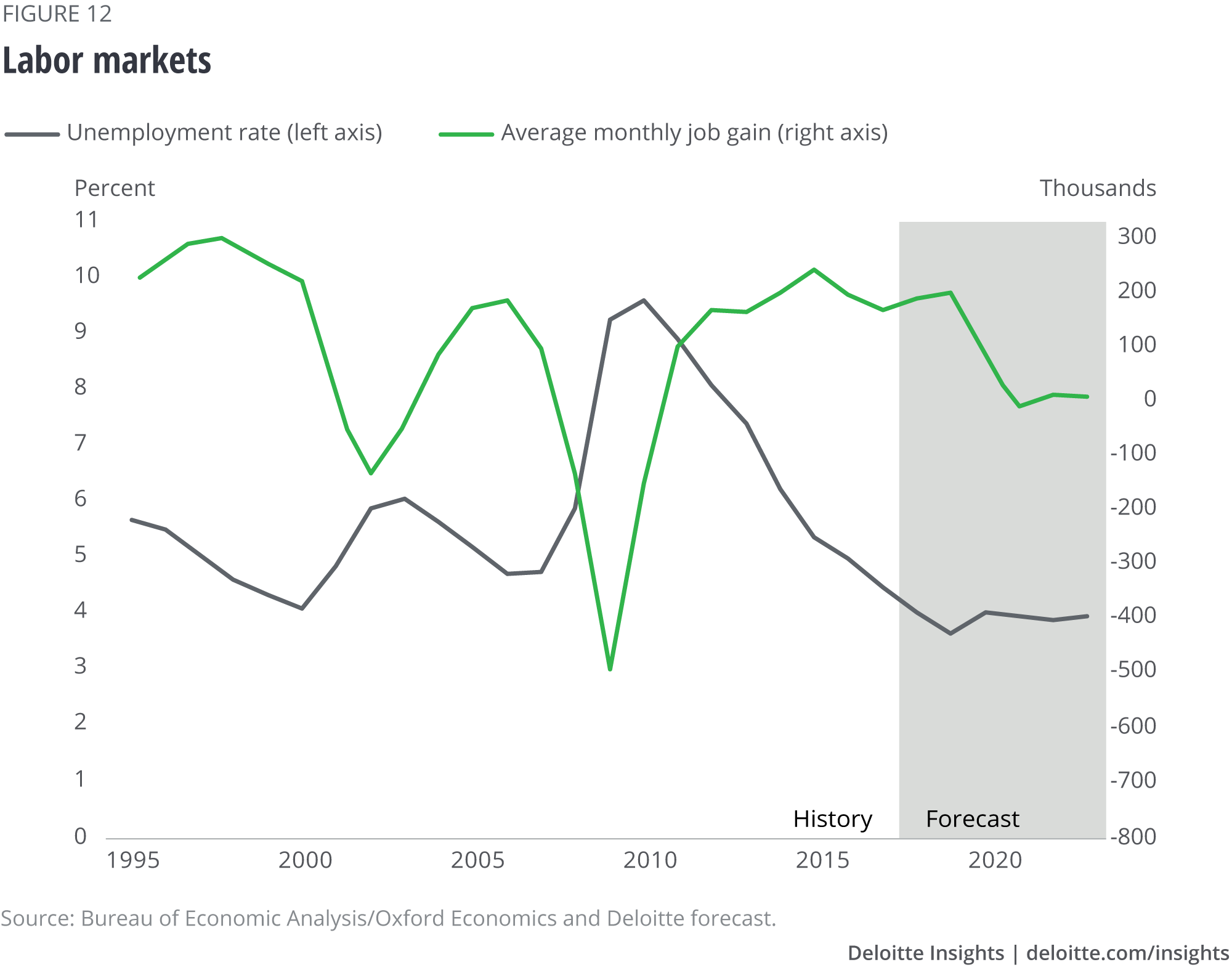

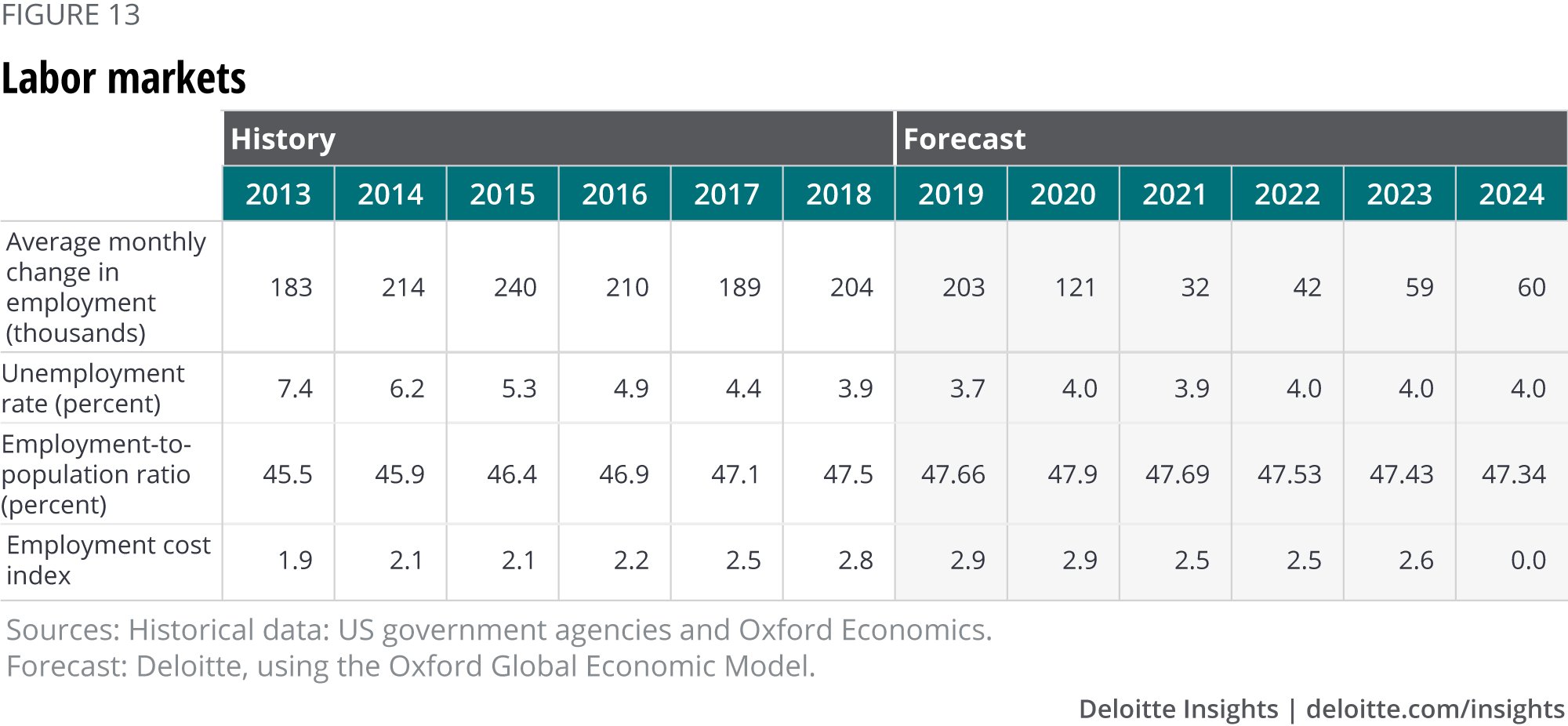

Labor markets

If the American economy is to effectively produce more goods and services, it will need more workers. Some potential employees remain out of the labor force, having left in 2009, when the labor market was challenging. Some are returning: The labor force participation rate for 24–54-year-old workers began rising in the middle of 2015, though after peaking in January, it has started to fall again. And it is still below the peak of over 84 percent reached in the late 1990s, suggesting that there may be a considerable number of workers who can be enticed back into the labor market as conditions improve. Our baseline forecast reflects that possibility.

Meanwhile, the labor force participation rate for over-65s is rising. At almost 20 percent, it’s much higher than the historical average—and it is certainly possible that, with better labor market conditions, employers can entice even more over-65s back into the labor force.

But a great many people are still on the sidelines and have been out of steady employment for years—long enough that their basic work skills may be eroding. Are those people still employable? So far, the answer has been “yes,” as job growth continues to be strong without pushing up wages. Deloitte’s forecast team remains optimistic that improvements in the labor market will prove increasingly attractive to potential workers, and labor force participation is likely to continue to improve accordingly. However, we are now close enough to full employment that average monthly job growth is likely to drop from the current 200,000 per month to about 100,000 per month in the next two years, even if the economy remains healthy.

In the longer run, demographics are slowing the growth of the population in prime labor force age. As boomers age, lagging demographic growth will help slow the economy’s potential growth. That’s why we foresee trend GDP growth below 2.0 percent by 2021: Even with an optimistic outlook on productivity, we expect that slow labor force growth will eventually be felt in lower economic growth.

Immigration reform might have a marginal impact on the labor force. According to the Pew Research Center, undocumented immigrants make up about 4.8 percent of the total American labor force.21 Immigration reform that restricts immigration and/or increases the removal of undocumented workers might create labor shortages in certain industries, such as agriculture, in which a quarter of workers are unauthorized,22 and construction, in which an estimated 15 percent of workers are unauthorized.23 But it would likely have little significant impact at the aggregate level.

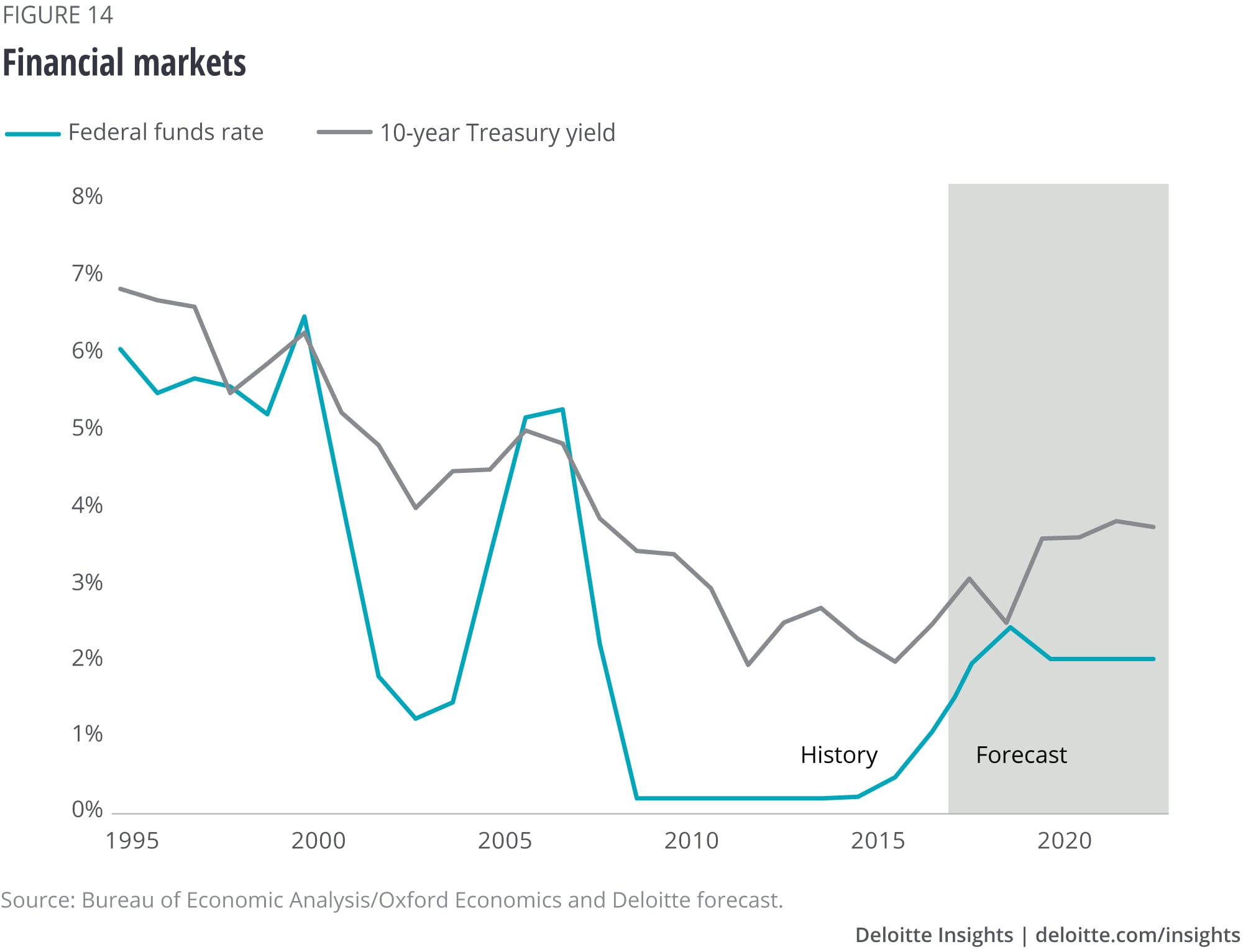

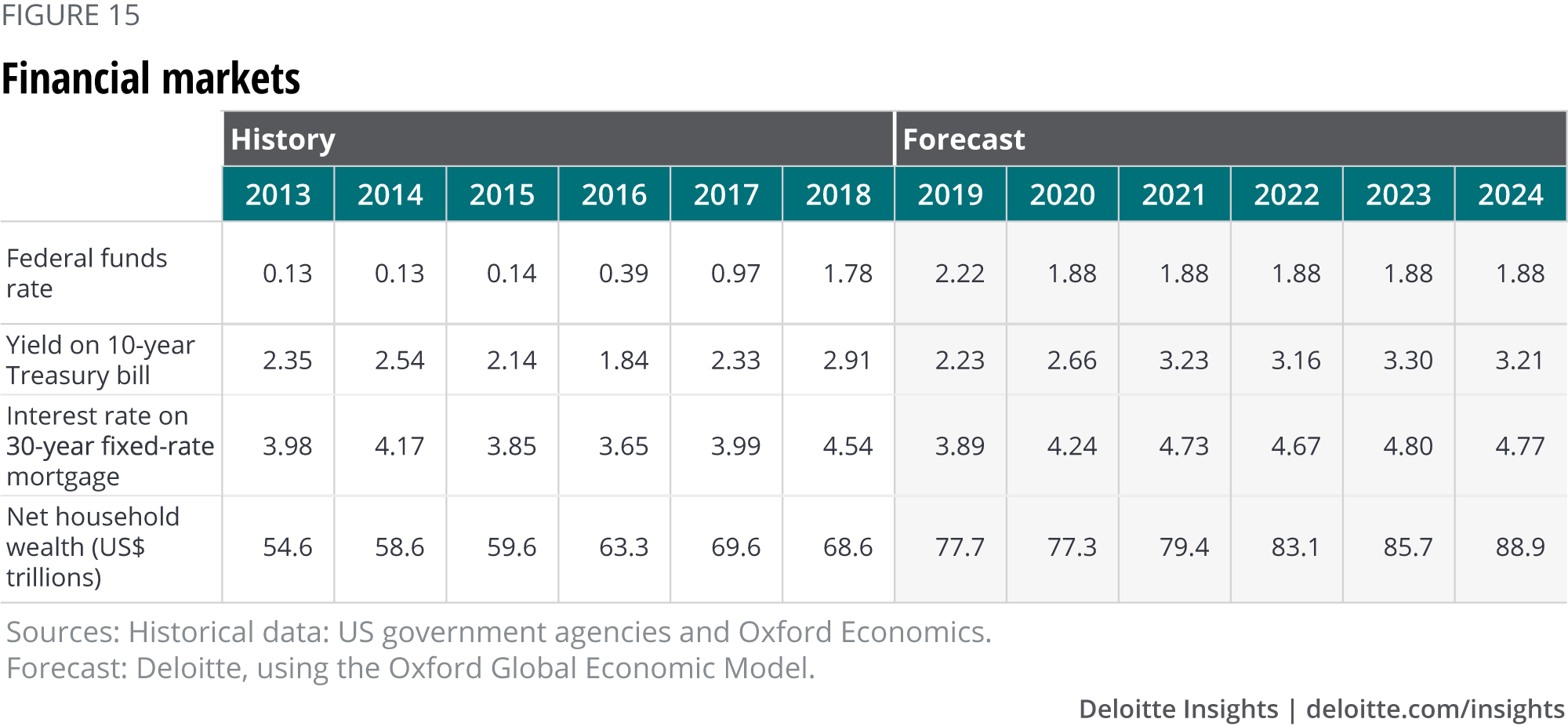

Financial markets

Interest rates are among the most difficult economic variables to forecast because interest rates depend on news—and if we knew it ahead of time, it wouldn’t be news. The Deloitte interest rate forecast is designed to show a path for rates consistent with the forecast for the real economy. But the potential risk for different interest rate movements is higher here than in other parts of our forecast.

Short-term interest rates are driven by Fed policy, and the Fed has changed direction remarkably quickly. As late as March, the median FOMC member’s projection of the funds rate called for an increase in 2020 to 2.6 percent. By the July meeting, the FOMC agreed to cut rates by a quarter point. Markets expect more cuts to come, although Chairman Powell tried to tamp down those expectations by calling the July action a “mid-course correction.” There’s no arguing, however, that the Fed is willing to keep rates quite a bit lower than Fed watchers might have expected when this tightening cycle started. Our baseline forecast now incorporates one additional Fed cut (in October). But the budget agreement will likely prevent the softer growth that the Fed would look for before cutting the Fed funds rate more than once.

The decline in long-term rates has been even more surprising. By mid-August, the 10-year Treasury bond yield was closing in on 1.5 percent. That’s about 50 basis points below the already-low rate in July. As long-term rates fell below short-term rates, analysts wrote quite a few stories about the yield curve reversal and its possible recession signal. The yield spread is troubling, although there is no need to panic (see sidebar, “Is the yield curve a modern-day Chicken Little”).

Is the yield curve a modern-day Chicken Little?24

The yield spread has turned negative, which means that long-term interest rates are below short-term interest rates. And the business media is full of people talking about how a recession must be just around the corner, because the difference between the yield on the 10-year Treasury note and the return on a short-term security (several are popular) has gone negative.

The spread reversal is certainly troubling, and markets have reacted. But it is no reason for panic. Now is the time for clear-headed leaders to develop contingency plans but not to overreact to the 24-hour news cycle.

How much attention should we pay to those commentators? The answer is more complicated than you might think. Yield spreads have indeed “predicted” every recession since 1969. The story for recessions before that is not so simple. But the accuracy depends on which yield spread you choose to follow. We’ll look at the difference between the 10-year Treasury note and the Federal funds rate, which is the measure that the Conference Board includes in its Leading Economic Index.25

This spread has indeed reversed prior to every recession starting in 1969. It also reversed from May 1966 to February 1967, then went positive again while the economy continued growing. And it reversed in January 1998 for one month and then in June to December 1998, before going positive again—with continued economic growth. That’s a record of predicting seven recessions and giving two false alarms.

An additional problem is the lag between the yield spread turning negative and the business-cycle peak (that is, the start of the downturn) is extremely variable. It’s taken anywhere from nine months (in 1973 and 2001) and 21 months (in 1969) from the first month in which the yield spread turned negative to the peak. So far, the yield spread (as measured by the 10-year to Fed funds spread) has been negative for two months, suggesting that the recession could start as early as February 2020 or as late as February 2021 and be consistent with historical experience.

Most important, however, is the fact that economists don’t know why the yield spread has turned negative before recessions. Recent Fed research on the empirical regularity stresses that, without a good theory to explain the data, we need to be a bit skeptical about its meaning.26

The regularity, then, does not imply that yield spread reversals cause recessions. That means that this time really could be different—if there is something unusual about financial markets, or about the next recession, that is different than the previous seven downturns.

The larger problem is the overall low level of long-term interest rates. The decline in interest rates is global, with a substantial number of countries—including economic powerhouses such as Germany and Japan—paying negative interest rates. In fact, about US$15 trillion in government debt now trades at negative rates.27

This has made a standard way of thinking about “normal” interest rates obsolete. It used to be a kind of rule of thumb that, in the medium term, a full employment economy would see a spread of about 200 basis points between the short- and long-term rates. Previous Deloitte forecasts assumed that the Fed would raise short-term rates to the 2.5 percent or even 3.0 percent level, above the targeted 2 percent rate of inflation. That argued for the key long-term rate in the forecast—the 10-year Treasury note yield—to move to 4.5 or 5.0 percent. This is becoming very unlikely over the next few years.

The current baseline assume that long-term US interest rates settle in at an equilibrium rate of around 3.0 percent during the five-year forecast horizon. This is lower than we previously forecast, and lower than historical experience would suggest. However, it’s hard to argue with the current state of financial markets, falling long-term interest rates, and (at such low rates) low demand for funds to finance investment projects over the past several years.

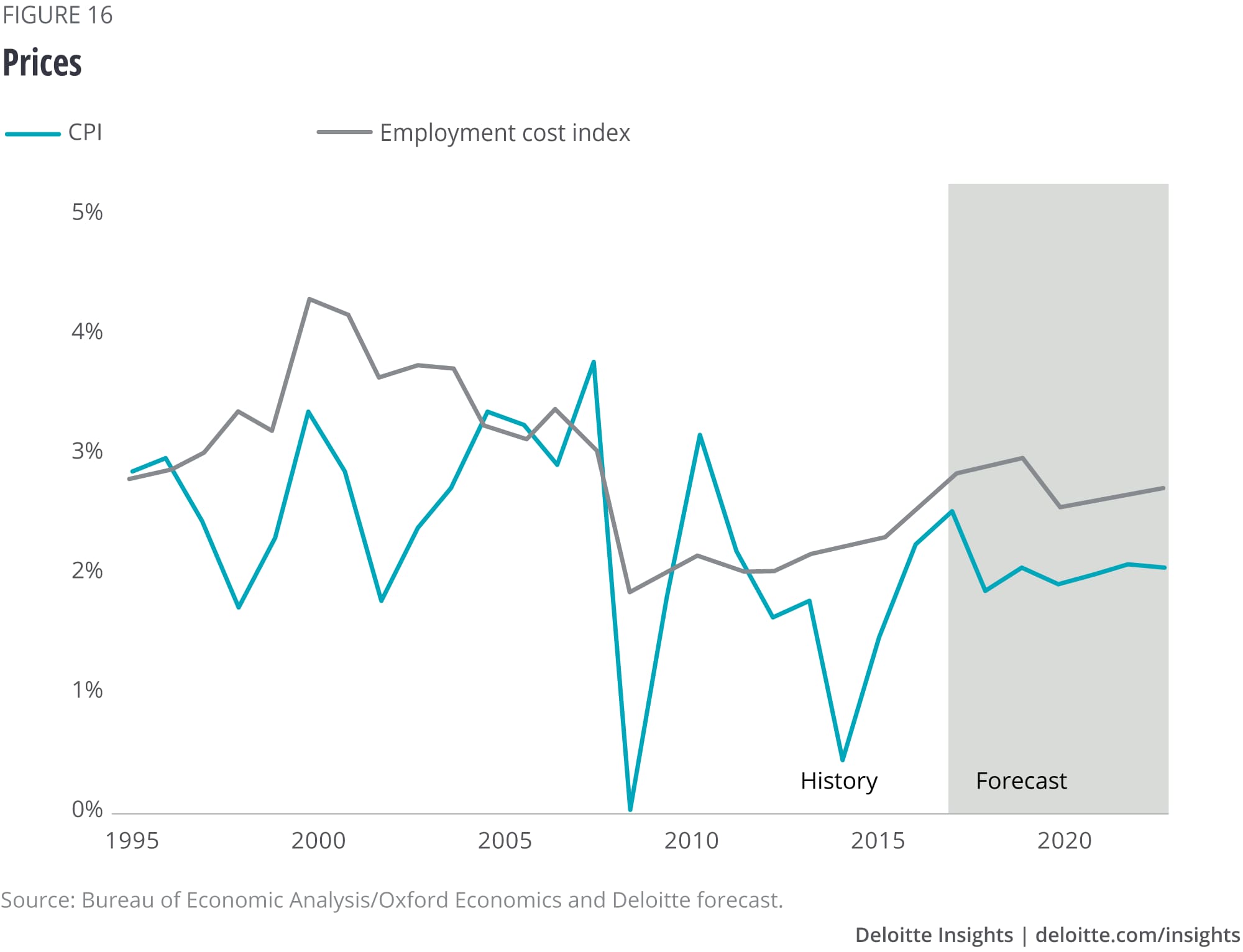

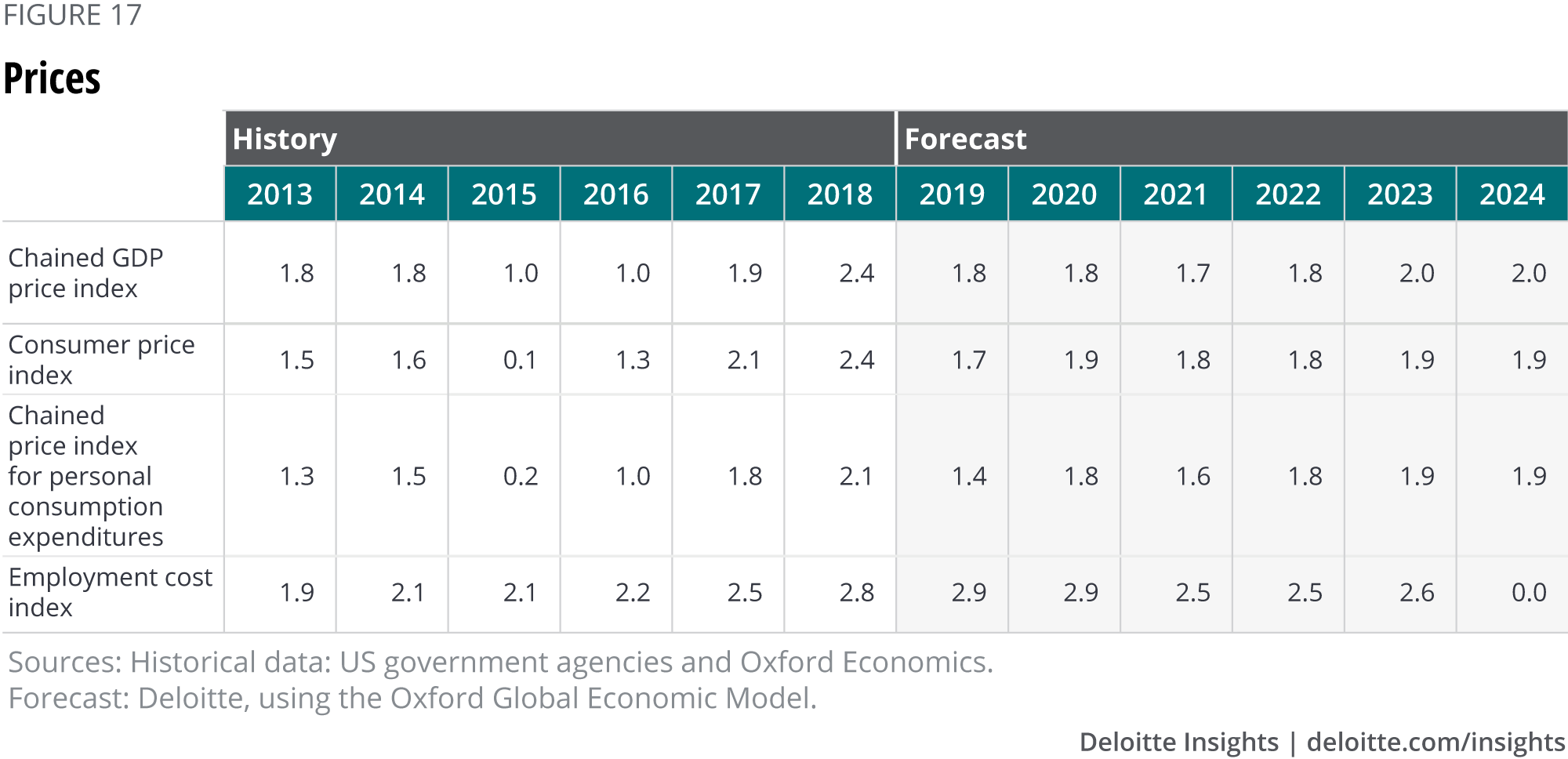

Prices

It’s been a long time since inflation has posed a problem for American policymakers. Could price instability break out as the economy reaches full employment? Many economists are increasingly wondering about this, as it becomes ever more evident that something is amiss in the standard inflation models. These models posit that, since labor accounts for about 70 percent of business costs, tight labor markets driving higher wages would be the main cause of accelerating inflation. The US unemployment rate has been below 4.0 percent for over a year. Yet unit labor costs grew just 1.9 percent in 2018, about the same rate as in the previous recovery, when the unemployment rate was higher. As long as businesses don’t face increasing costs, it’s hard to see what could drive a sustained rise in goods and services prices.

But it’s also quite possible that the economy simply hasn’t hit full employment. Despite unemployment dipping below 4.0 percent, the labor force participation rate for prime-age workers remains about two points below the rate before the financial crisis. Two percent of the prime working-age population suggests that about 4 million more people could be enticed into the labor force under the right conditions. Whether those people are available is unclear, and many economists are debating the issue fiercely.28 The combination of low labor-cost growth and continued high employment growth suggests that people are likely being enticed back into the labor market.

At some point, however, the combination of the tax cut and spending increase could create shortages in both labor and product markets and, as a result, some inflation. And tariffs are something of a wild card. Although most of the tariffs have been on intermediate products, there is evidence that the additional cost was simply passed through to final consumers.29 The most recent tariff increase included more consumer goods and may be felt directly in the CPI. Interpreting inflation data under those circumstances could be tricky. And if that rise sparks wage hikes to maintain real wages—a possibility at current unemployment rates—inflation could indeed tick up.

A return to 1970s-style inflation is about as likely as polyester leisure suits coming back into style. But it would not be surprising in these circumstances to see the core CPI rise to above 2.5 percent. Even in the faster growth scenario, though, it wouldn’t require a lot of Fed action to keep a lid on prices.

Appendix

Explore the economics collection

-

China economic outlook, February 2023 Article1 year ago

-

Brazil economic outlook, November 2024 Article1 week ago

-

How the financial crisis reshaped the world’s workforce Article5 years ago

-

Retirees of the future Article5 years ago

-

What is US national income telling us? Article5 years ago

-

Understanding the economic impact of US midterm elections Article6 years ago