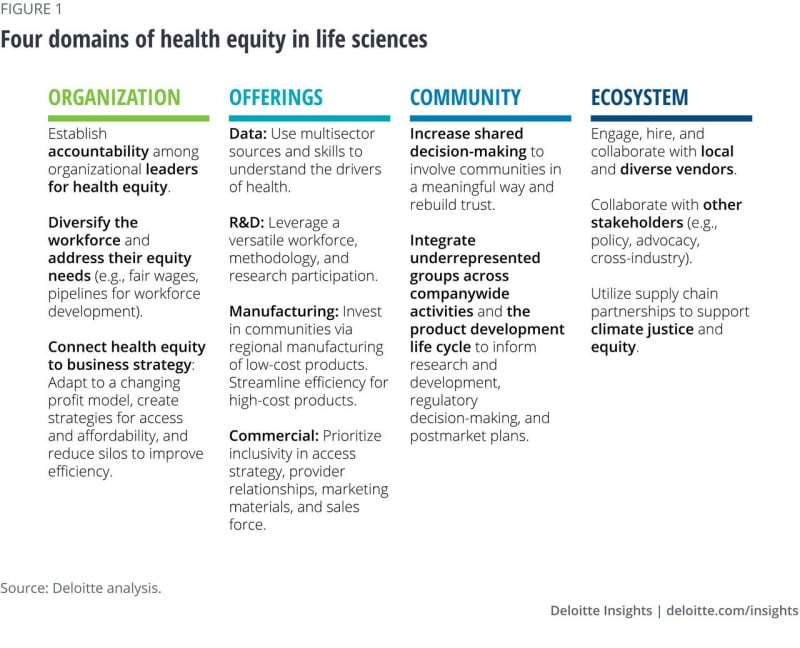

Organization: Activating health equity internally

Within the organizational domain, the primary consideration is addressing diversity, inclusion, and equity within the workplace. Part and parcel of that approach is taking concrete actions on accountability, workforce needs, and business strategy to help address the health and operational priorities of your own employees and business.

Accountability: Organizational leaders—both those at the top and throughout departments—should be held accountable for health equity measures; and this should be reflected in compensation, incentives, and bonuses at all levels, including the salesforce. This is important for the sustainability and success of health equity throughout the company. Many times, organizations can add health equity measures to existing performance measures, rather than developing completely new sets of key performance indicators. These measures can be even more tactical in the beginning such as increasing the number of health-equity discussions across the team. Accountability also includes having a plan of action if/when progress isn’t made.

Some external entities are taking notes and holding life sciences companies accountable as well. For example, the 8th Access to Medicine Index assesses how the 20 top pharmaceutical companies perform on ensuring that people living in low- and middle-income countries have access to the medicines, vaccines, and diagnostics they need.9 The Good Pharma Scorecard ranks pharmaceutical companies on their bioethics and social performance, measuring accessibility of medicines and marketing practices, among others.10

Workforce needs: More diverse workforces have shown time and time again that they are more creative and better for business.11 Yet, the life sciences industry lacks diversity across multiple measures.12 Efforts to increase diversity should begin early. Teaching students about possible scientific career paths early on is one way to do this. Finding ways to hire, retain, and mentor employees through thoughtful engagement and programs are other ways to increase and sustain diversity.

Other ways companies can make improvements now is by providing anti-racism and unconscious bias training and listening to employees about their most pressing health needs.13 When organizations focus on improving health equity for their own employees (by providing fair wages, comprehensive health insurance, pipelines for workforce training and development, etc.), they can potentially share in the estimated US$1 trillion in savings over the next 10 years in reduced absenteeism.14

Business strategy: Life sciences companies are facing pressure to improve the accessibility and affordability of their products, both in the United States and globally. This could present an opportunity for life sciences companies to reevaluate their business model and a way to improve their operational efficiencies. While change management can be difficult, with committed leadership and governance structures, life sciences companies can make this transition successfully.

- Profit model: In the United States, the shift to value-based care is progressing: The total number of publicly announced innovative contracts, including value-based contracts, and flexible contracting arrangements (pay-over-time, subscription models) increased from just three in 2009 to 99 in 2021.15 The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services is working to further this effort, as evidence-based purchasing rules.16 As this trend gains traction, it will be important for life sciences companies to create equitable products to better demonstrate how they work across diverse patient populations and prevent poor outcomes.

- Access: Addressing health equity can support life sciences companies in growing their total addressable market by looking at patients who already have a condition but do not currently have access to therapies or have low usage. For example, a 2021 study highlighted significant racial-ethnic disparities in the use of diabetes technology (such as insulin pumps and continuous glucose monitors) among young adults with type 1 diabetes.17 Young adults who identified as Black or Hispanic were less likely to have access to diabetes technology. By reaching these patient populations, life sciences companies can gain access to currently untapped markets. Even if the percentage margins are lower, the prevalence in need can increase the overall operating income and potential profitability as they capture greater economies of scale.

- Affordability: Companies should also reassess how they manage their products as patents expire. One avenue is manufacturing their own generic, which can be a viable approach in the market and provide additional quality assurance, as the company will have oversight of the generic, ensuring it’s equivalent to the original product. On the other end of the spectrum, the high cost of biologics and biosimilars,18 while likely to decrease over time, is currently creating a substantial equity dilemma that should be addressed.

- Efficiency: The current silos among the research and development, manufacturing, and commercial departments may not facilitate knowledge sharing and can be a missed opportunity to increase consumer touchpoints and trust. Companies should rethink how products are brought to market throughout the product life cycle, including new go-to-market models designed with health equity at the forefront.

The diversification of research design and execution can generate products that reach new populations in different ways or existing populations in better ways. Lessons learned during clinical trial recruitment and execution, as well as relationships with diverse trial sites, can be important enablers for the commercial organization as products prepare to launch. Manufacturing with equity in mind can increase market access and support community well-being. The commercial field force can then leverage these relationships to help deliver products and services more effectively. Learnings from commercial efforts can then feed back into research and potentially inform customer and user inputs and requirement specifications. Creating an organizational governance model to share learnings can strengthen this coordination and help ensure that health equity is embedded at the start of development.

Offerings: Taking a coordinated approach to drive equity across the value chain

To help ensure their offerings are equitable, life sciences companies should evaluate whether their products and services are generating health and well-being for consumers. The same premise applies to companies’ algorithms, whether they inform offerings or are consumer-facing products themselves.

Across the product and service development life cycle, equity can be integrated into data and measures, research and development, manufacturing, and commercial efforts. Here are a few ways that companies can align their offerings with the needs of diverse consumers:

- Expand data measures and skills to understand the impact of social, economic, and environmental factors and to tailor actions. Equitable data can inform the degree to which companies understand the needs of diverse populations and the factors that can impact product utilization and effectiveness. This may require leveraging varied data sources, examining a broader range of outcomes, and engaging multidisciplinary skills and resources.

Combining multiple forms of data, such as claims, electronic health records, and drivers of health can clarify health inequities and inform related strategies. A recent study combined patient-level demographic, clinical, and mortality data with neighborhood-level economic advantage data to understand survival rates for nonmetastatic breast, prostate, lung, and colorectal cancers.19 The researchers found that neighborhood disadvantage was associated with worse survival even after adjusting for patient-level income.20 The health impact of neighborhood-level factors, among others, is important for life sciences companies to understand as they develop products and services to reduce mortality.

In addition to expanding data inputs, companies should examine a broader range of outcomes, including patient-reported outcomes and patient experiences. Prior research shows that patients’ interactions with front office staff and their perception of the cultural sensitivity of staff impact their satisfaction with the care they receive and their ability to adhere to treatment.21 This insight can inform efforts to address barriers to product utilization.

Multidisciplinary skills are needed to interpret inclusive data. Explaining racial effects requires knowledge of social constructs22 and how bias leads to biological stress, such as allostatic load, which is more prevalent among non-Hispanic Black and Latino adults.23 Furthermore, effects vary not only across races but also within races.24 This knowledge, among other factors, has implications for building more equitable algorithms. Our prior research provides suggestions to examine bias in analytics and discusses the positive social and financial impact of these considerations.25

Companies can use analytics resources from other stakeholders and should be mindful of ethical considerations26 for inclusive data practices. The Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America’s equity initiative includes data infrastructure investment that can be used to improve the accurate measurement of health disparities.27 The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) data equity principles and collated resources provide guidance for using public health data to drive equity.28 Furthermore, the CDC’s Data Modernization Initiative serves as a resource to improve the collection, consolidation, and sharing of equity-related data, as well as strengthen workforce capacity to improve data use.29

- Strengthen research and development through infrastructure, methodology, and participation. Embedding health equity within research and development allows companies to create products that may be better suited for diverse populations. Investments in equitable approaches to these components could help companies attract multidisciplinary talent, increase market reach and penetration, and support regulatory compliance. Here’s how to help build equity across the three components:

Infrastructure: An extension of activating health equity at the organizational domain is cultivating a diverse scientific workforce to support research and development. A diverse workforce can increase representation of community talent, needs, and experiences to help inform the early stages of the product development life cycle. Government and educational organizations are working on pipelines and strategies to improve diversity in the scientific workforce,30 and life sciences companies can leverage this infrastructure, as well as their own programs, to build multidisciplinary teams and enhance their talent.

Methodology: While randomized controlled trials are the foundation of clinical research, they are designed to assess efficacy under ideal settings, often with restrictive exclusion criteria.31 This can leave critical gaps in understanding real-world effectiveness to drive changes in care. Pragmatic clinical trials fill these gaps by meeting people where they are to understand the impact of social, economic, and environmental factors32 on health and outcomes.33 These same drivers of health contribute to health inequities and understanding their impact can produce more robust products and services, increasing market penetration. Conducting pragmatic clinical trials requires the understanding of the effect of real-world conditions, as well as operational guidance. Having a more diverse scientific workforce and using resources such as the National Institutes of Health Pragmatic Trials Collaboratory34 can help address these needs.

Participation: Research and development processes need more diverse participants to help build products and tools that are effective in different populations. This participation can also support regulatory compliance, such as the US Food and Drug Administration’s requirement to submit clinical trial diversity plans.35 Our prior research provides strategies to help diversify participation related to building networks of site locations, fostering community relationships, enhancing communication, and standardizing participation platforms and metrics.36 We expanded this research to focus on identifying trusted community resources, ways to reduce participation burden, and opportunities for decentralized and community-based clinical trial sites.37

- Improve access and community benefit with equity-centered manufacturing. Equity-centered manufacturing approaches can offer several opportunities to increase trust and market share. Regional manufacturing is one way to invest further in diverse communities. Increasing the regional presence of products with lower manufacturing costs through local facilities can allow companies to employ local talent and upskill communities by providing them with leadership development opportunities.38 This can strengthen community relationships and foster trust to improve market penetration. Additionally, regional investments may address inequities in access. As we saw with the COVID-19 pandemic, low-income countries lagged middle- and high-income countries in their vaccination rates. One of the factors behind these inequities was the limited access to local vaccine manufacturing.39

For high-cost products, reducing cost inefficiencies can improve affordability and increase diverse market share. Multistakeholder interest in “advanced manufacturing” may also support efforts to increase access and improve time to market.40 Companies can also advocate for more inclusive policy coverage changes and offer generics to improve accessibility. Overall, these approaches can address not only inequities in product utilization, but also intervene on workforce and community needs that lead to health inequities.

- Focus commercial offerings on providers and patients. Like other areas, commercial strategies will need to evolve to drive greater health equity. Companies should create more inclusive, meaningful relationships with new and existing providers and patients. Collaborations and partnerships may be helpful in achieving these goals.

One avenue is to reevaluate which providers the company has already established relationships with and where new relationships can be created to help increase patient access to therapeutics. To build bridges to diverse populations, companies can work with more diverse providers, who are more likely to care for underserved populations.41 These relationships should be approached in a culturally humble way to minimize a sense of extraction. Expanding relationships with existing providers can also be important, as they may be able to reach patients who have not been included previously. Working with physicians, nurses, and pharmacists and engaging in peer-to-peer learning are important strategies, given the time patients spend with the broader care team.42

Creating culturally relevant and patient-centric communications (multichannel marketing through brochures, websites, television ads, etc.) can be a significant way to reach new populations and develop deeper relationships with existing populations. Demographic markets are nuanced and go beyond race and ethnicity to also consider age, gender, economic status, and their intersections. Culturally informed content is not one-size-fits-all and should be tailored to consider the differences between groups that share the same race but different ethnicities and languages, or between groups that share the same gender but different income and ages. Patient education should also account for health, digital, and financial literacy.

A company’s market access strategy should also be considered with a health equity lens. Companies should think about how their pricing strategies can help improve access for underserved populations, how the structure of reimbursement processes can create additional burdens for patients, and how patient eligibility criteria may exclude those who would benefit from access, among others.

Diversifying and upskilling the sales and marketing teams is an important part of doing this well. As the direct touch point with health care workers, the sales force should understand how to talk about health equity in a culturally humble way, recognize their own unconscious biases, and develop strategies for calling providers into the conversation. This could help build trust in new and existing relationships.

Community: Bring in stakeholders’ voices to help achieve equitable health outcomes

At the community domain, organizations should examine how to collaborate with the communities they recruit from, operate in, and invest in, and incorporate their voices to help them achieve sustainable and equitable health outcomes and rebuild trust. This approach can support health equity by increasing the visibility of underrepresented populations and helping to ensure that organizational products and activities are designed and conducted with these populations in mind. Community involvement can generate organizational returns on engagement43 and, more broadly, improve the understanding of community perspectives shared in other ecosystem activities such as regulatory committees and hearings.44

What is important for community engagement? The community domain encompasses a broader continuum of community involvement or community engagement.45 This can range from simple outreach activities where focus is “to inform” the communities, to mid-level involvement and collaboration where interactions are increasingly bidirectional, to shared leadership where final decision-making happens at the community level. It is important for life sciences organizations to examine their community engagement efforts and gauge the range of different levels of community involvement. Engaging the community at this level may take time and can be challenging, but ultimately, it should result in greater shared decision-making.46 If the majority of the community engagements are concentrated at low levels where communities are simply passive stakeholders, it can reflect inequities in power.

What activities can community voices strengthen? Several examples from the US National Health Council and the Clinical Trials Transformation Initiative show how patient engagement, a form of community involvement, can inform research and development, regulatory decision-making, and postmarket plans.47 Across the clinical trials continuum, patients can inform the research question, support trial awareness, facilitate informed consent, and disseminate results. Community-based participatory research is a highly collaborative approach that can guide community involvement in research. At the regulatory and postmarket levels, communities can identify patient-focused factors to integrate into benefit risk assessments, participate in regulatory hearings, share product information, and advise on postmarket surveillance activities and findings.

Ecosystem: The power of partners and collaborators

Across the ecosystem domain, the ultimate question is how companies can leverage the full power of the supply chain and other partners to amplify their positive impact on the industry and society through intentional and equitable relationships, policy advocacy, and public action. Advancing equity, and ultimately ensuring better health for the whole world, can be a monumental task, and it is unlikely to be achieved by one stakeholder. Therefore, life sciences organizations should look for opportunities to collaborate with other ecosystem players to multiply the impact and realize health equity for all.

Engaging, hiring, or collaborating with local and diverse vendors (e.g., contract research organizations, suppliers, etc.) is one of the key steps that life sciences organizations can take under this domain. For example, a medical device company is collaborating with the Local Initiatives Support Corporation to expand and empower diverse small businesses that provide health care companies with manufacturing and essential products. This initiative aims to boost economies in underinvested communities, create jobs, enhance diversity, and tackle systemic barriers.48