A more immersive, instantaneous, and intelligent internet is inevitable

The next evolution of the internet will inevitably include a highly immersive metaverse powered by AI, with near-instantaneous interactions made possible through advances in connectivity.

This is inevitable for two reasons. The first is generational gravity: Increasingly, the youth are spending more time in virtual, immersive worlds and using AI tools. Roblox, a popular metaverse gaming platform among young people, has 50.4 million daily active users worldwide.1 Other early metaverse platforms such as Fortnite, Zepeto, and Sandbox also boast millions of users. The generative AI tool ChatGPT has outpaced the growth of any prior technology and accumulated 100 million users in two months,2 with the majority of its users aged between 25 and 34.3 A recent United Nations report also found that 93% of youth have a positive perception of AI and robots, with 80% interacting with AI multiple times a day.4 As this population becomes active consumers, by 2030, the notion of living in these intelligent virtual worlds will come naturally to them. For the younger generation, these interconnected “phygital” worlds—a blend of physical and digital—will become the norm that they gravitate toward in both work and life, not just in the realm of games. Their demand for these experiences will shape the evolution of the internet.

The second is technological gravity: A large volume of capital from big technology firms and investors is flowing into metaverse and AI technologies. At the time of writing this article, Microsoft is in the process of acquiring Activision Blizzard for US$70 billion and has made a multibillion-dollar investment in OpenAI5; Meta (formerly Facebook) spent US$10 billion on the metaverse in 20216; and SoftBank invested US$150 million in Zepeto, one of Asia’s most popular metaverse platforms.7 In 2022, the trend continued, with a US$65 billion metaverse market,8 while global funding for AI amounted to US$48 billion.9 By 2025, 5G networks will likely cover one-third of the world’s population, which will provide the technical infrastructure to enable low-latency connections and support an instantaneous metaverse.10 With these large investments, the next-generation internet is already in the process of being built and will connect millions of users simultaneously in persistent, immersive worlds that bridge the physical and digital.

Toward a human-centered next internet

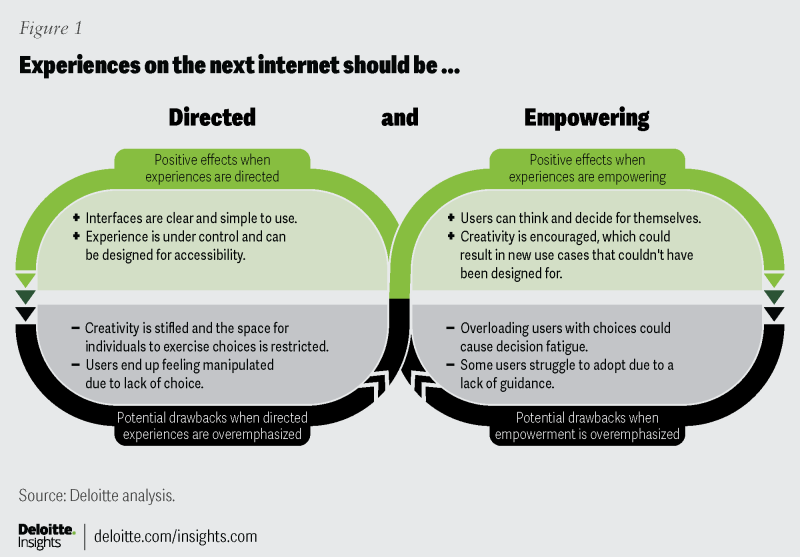

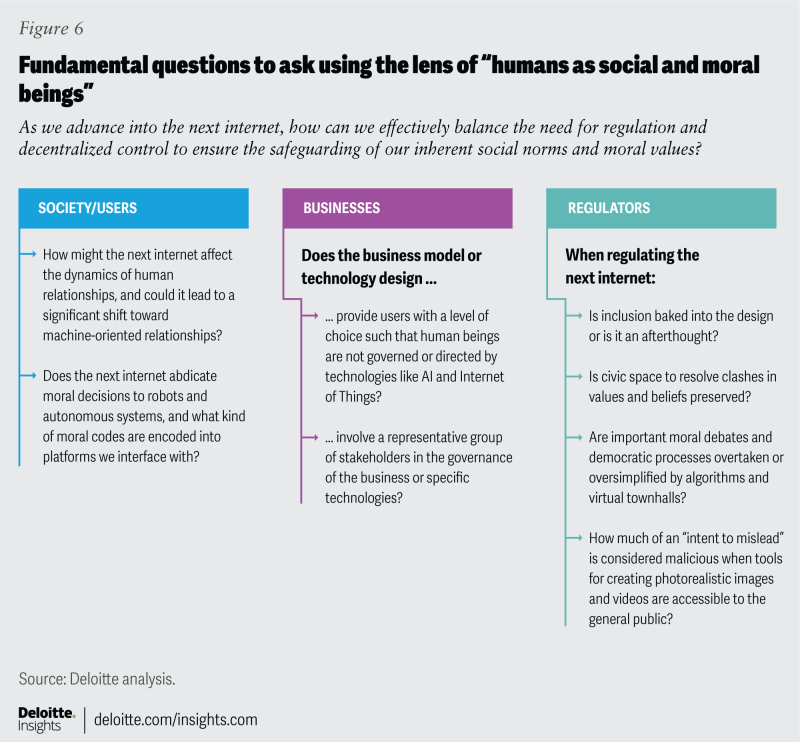

An immersive and intelligent internet is inevitable, but a human-centered one is not. Businesses, regulators, and society at large should confront key questions related to its development today to ensure that the internet and associated technologies elevate us as human beings.

When game-changing AI tools such as OpenAI’s ChatGPT and Google’s Bard were introduced, many users were initially amazed by their capabilities. This amazement quickly turned to fear about their roles and relevance in a world where AI can perform so many types of tasks.11 These concerns, among others, prompted top AI industry experts to sign a petition calling for a temporary halt to the development of AI that is more powerful than OpenAI’s most advanced system, GPT-4.12

The metaverse is prompting concerns as well.13 Virtual humans and interactions in the virtual space can be novel and convenient, but they can also be dehumanizing and unhealthy if not designed well. Concerns around safety are shaping up to be a key component of the discourse around the metaverse. For example, India’s upcoming digital regulatory framework, Digital India Act, has explicitly mentioned that it will investigate crimes in the metaverse that spread misinformation or incite violence.14

If the next evolution of the internet is being shaped by technologies such as generative AI and the metaverse, will it prioritize efficiency and incentives over authenticity, diversity, and safety? How can we ensure that it aligns with our values, identities, and self-worth, amplifying and augmenting human endeavors? As we transition into this new digital landscape, organizations that prioritize their ability to cultivate more sustainable growth models will recognize that it is crucial to look beyond today’s bottom line and consider these technologies’ impact on humanity.

We should ask the right questions as we navigate this new reality, and we should start now. We put forward a framework to start questioning what the next evolution of the internet should consider to ensure its human-centricity. After all, if the future internet can present all the answers, asking questions may be the most human thing to do.