Perspectives

The Deloitte Research Monthly Outlook and Perspectives

Issue LII

1 November 2019

Economy

Bracing for a slowdown

China's continued economic resilience in the face of a global slowdown and the continuing trade war clearly points to the fact that its policy framework should focus on structural reform or a faster pace of liberalization (financial sector in particular) and refrain from unleashing a large fiscal stimulus. This has been our position for some time and the Q3 GDP growth of 6% has not shaken it. Unlike economies in crisis, China still has much policy leeway in the sense that certain reforms could be undertaken without sacrificing the growth target of around 6%. This seems to have been understood by policymakers as not long ago the government announced its decision to do away with the foreign ownership ceiling of asset management companies. In the short run, we believe that the best policy response to the present situation is a continued implementation of better market access for both foreign companies and private enterprises. This will make further escalation of the ongoing US-China trade war more difficult.

However, what Q3 GDP growth rate figures have done is reignite the eternal debate on whether policies should be more pro-growth or not. If economic deceleration continues, it is conceivable that the growth rate will dip below 6% in coming quarters. But should this really be a cause for concern? A GDP growth target is set for the chief purpose of maintaining social stability. In China, social stability is about job creation. At the height of the Asian Financial Crisis, Premier Zhu Rongji had pledged to deliver 8% of GDP growth. A widely accepted view then was that 1% of GDP growth could be translated into 2 million jobs. But this kind of relationship between growth and employment no longer holds true as in recent years the Chinese economy is undergoing profound structural changes, consumption playing an increasingly important role as a driver of growth and the service sector now employing many people though not necessarily contributing much to a high GDP growth rate.

In most developed and some emerging markets, the Philips curve, a basic economic theory on the trade-off between inflation and the unemployment rate, is being challenged. Intuitively, a tight labor market should cause higher inflation and hence, policymakers will respond with a tighter fiscal policy or raise interest rates or do both. But today the reality on the ground is that there are scant signs of inflation in the US economy and unemployment rates have hit an all time low. But, far from raising interest rates, the Federal Reserve is likely to cut interest rates twice in 2020 based on fears of a possible economic slowdown caused by the trade war. Would the frustrations faced by western central banks (the Fed, ECB and BOJ) to reflate their economies justify a greater dose of fiscal stimulus in the West? The ECB is clearly moving in that direction with its continued QE which, if looked at closely is really nothing less than a quasi-fiscal expansion. In China today, growth is decelerating while inflation is slowly creeping up (the September Consumer Price Index has exceeded 3% for the first time since November 2013). Of course, this is mainly due to the surging pork prices caused by the African swine fever virus which suggests that an overshooting of inflation remains unlikely in 2020. In the final analysis, with low interest rates in most economies, it is becoming tempting to resort to fiscal stimulus.

However, China's situation is very different from most developed nations where growth is likely to be sluggish in 2020 (except the US). The floor for China's economic growth rate is around 4%, largely due to confident consumers, and assuming investment and trade do not make any contribution to GDP growth. Of course, the Chinese economy is unlikely to grow at as low a rate as 4% in 2020. Our baseline scenario ranges between 5.5% and 6% in 2020 assuming that there will be a moderate stimulus. This could come in the form of a mild adjustment of the RMB exchange rate, always a good option for boosting exports and enhancing the effectiveness of monetary policy. In developed countries, efforts are also being made to introduce measures that will have the effect of automatic stabilizers (e.g., unemployment benefits), kicking in when a downturn occurs. But in China, since policymakers could easily approve big projects with accommodative bank lending, there is always a risk of overdoing the fiscal stimulus as in late 2008.

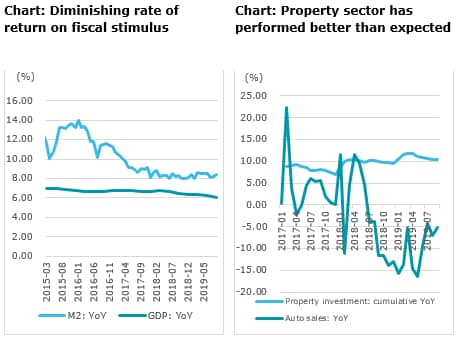

The main source of China's economic slowdown is a legacy of past stimulus (leverage and excess capacities) as it has become abundantly clear in recent years that credit has a diminishing rate of return in terms of generating headline growth.

Yet, 2019 has seen a policy U-turn on the de-leveraging campaign as official narratives have put "structural adjustment" on the back burner. Meanwhile, there has been greater emphasis on poverty reduction with a stated goal of realizing a total "elimination of poverty" by 2020. In terms of policy implications, this means that China recognizes the need to achieve greater fairness - perhaps at the cost of bank asset quality. In our view, this is the right policy in light of the widening income disparity in China (the Gini coefficient for China has been creeping up since 2015 and has reached a score of 0.468 in 2018, when 0.4 is the warning level set by the United Nations). If de-leveraging continues to be put on the back burner in 2020, (a plausible policy choice when corporate investment has been adversely affected by supply chain uncertainty even with the US-China truce in place), then it would be better for consumers rather than corporates to increase leverage and for zombie companies to be gradually weeded out (meaning some reduction of excess capacity). The key question is whether consumers would remain confident in the face of a slowdown or slide in the economic growth trajectory to 5-6%.

The answer to this lies in the housing market. So far in 2019, the real estate sector has performed better than most people expected. Housing prices are stable in most cities while property investment is growing at around 8-9%. Why are developers stepping up their investments in the face of reduced expectations of asset inflation? One plausible explanation is that the cost of financing is still fairly affordable. Though China has not joined the global monetary easing chorus, the PBOC has been using policy tools to improve liquidity and to guide interest rates down. In urban China, pent-up demand remains strong partly due to a cultural preference for homeownership and partly due to the absence of other sound investment vehicles. To spur growth, the Government could simply relax restrictive policies on home purchases as China still has much room to increase urban populations. In conclusion, the property sector has turned out to be the bright spot in an otherwise troubled 2019, while the auto sector has been a disappointment. We could argue that sluggish auto sales are a global phenomenon. But, from a car ownership perspective, China is still an emerging market compared to countries with a comparable per capita income (e.g., Brazil and Malaysia). The phasing out of rebates and higher emission standards explains the drag on car purchases in China in the short run, but the convergence trend with countries like Brazil in terms of car ownership, fueled by underlying unfulfilled consumer demand, does suggest that China is far from a mature car market and hence there is little real cause for concern.

In conclusion, we see slower growth in 2020 but we also see little need for China to embark upon major pump-priming. The uptick in inflation caused by the African swine disease is more than likely to be transitory. As such, a managed gentle slide of the RMB will be a better reflation tool provided China can significantly improve market access.

Retail

Foreign hypermarket operators regroup in China

In the mid-1990s, foreign retailers such as Carrefour and Metro introduced the hypermarket model to China, ushering in a new era in shopping experience for the Chinese consumer. Today, a little less than a quarter of a century later, explosive growth in China's retail market has meant that the competitive advantages of foreign hypermarketshas disappeared. Metro group, the German retail giant that opened in China 24 years ago, has agreed to sell its China operation to WuMart Technology Group. Both companies will establish a joint venture company of which WuMart owns 80%. Metro will hold the remaining 20%. Just three months earlier, Carrefour, another pioneer foreign retailer, sold 80% of its China business to Suning. This leaves Walmart as the only one amongst the top three foreign hypermarket operators in China since the mid-1990s, keeping 100% control of its China operation. But a closer look at Wal-Mart's business in China shows that its hypermarket stores are also shrinking. By the end of first half of 2019, Wal-Mart had closed 14 stores nationwide.

What has led to the demise of the 100 percent owned foreign hypermarket? Possibly the single most important factor in this is the rise of ecommerce.

With the rise of the Internet, physical barriers to consumption have disappeared. Consumers can buy what they want whenever and wherever they want. Intense competition in ecommerce has meant that personalization and diversification have become the norm. Hence, the mindset of the Chinese consumer has changed. For today's consumers, the value of shopping not only lies in the goods they buy but also the "experience" they encounter. Consumers want to enjoy an efficient and convenient shopping experience at any time and in any place. Conventional hypermarkets are not able to meet the needs of today’s consumers - which is why they are no longer the first choice of most Chinese shoppers.

When hypermarkets first opened in China 24 years ago, people rushed and bought everything. That market has almost nothing in common with today’s market — which is one in which only the fittest can survive. In today’s brick and mortar retail world, foreign operators are not only competing with local hypermarkets such as Yonghui Supermarket, WuMart and CR Vanguard but also with convenience stores, such as the FamilyMart, 7-Eleven and Lawson. Ecommerc giants Taobao, Jingdong and Pinduoduo have also changed consumers' consumption habits by providing them with a value for money, efficient shopping experience. In addition, with the new retail supermarkets opening both online and offline operations, foreign hypermarket operators are trapped in an old business model that gives them little room to maneuver over local competitors.

As China's economy kept growing, the operating costs of foreign retail enterprises in China also increased dramatically. The existing hypermarkets, which were in any case moving towards saturation, saw their profits being increasingly eroded by the newcomers. In the face of low profit margins, rising operating costs and an unwillingness or incapacity to transform their business model, it became imperative to sell their equity in order to avoid further losses.

|

Enterprise |

Entry time in China |

Strategy in China |

Status |

Pre-ecommerce |

Carrefour |

1995 |

All hypermarkets with affordable prices, stores in Tier 1-4 cities in China |

Suning acquired 80% of its China company |

Metro |

1995 |

Hypermarkets - high-quality products, strictly business membership system was implemented until 2013. From 2013, consumers can apply free membership, outstanding supply chain and B2B business. |

WuMart will hold 80% stake, Metro will retain 20% stake |

|

Wal-Mart |

1996 |

Hypermarket, affordable prices |

Currently, building community-oriented stores |

|

Post e-commerce |

Costco |

2014, opened its online store on Tmall 2019, opened physical store |

Low prices, strict selection, low SKUs, mainly imported goods |

1 physical store in Shanghai

|

ALDI |

2017, opened its online store on Tmall 2019, opened physical store |

Affordable prices, middle and high-end market positioning in China, new style market , mainly fresh and imported goods |

5 physical stores in Shanghai |

The future of the foreign retailer in China may look a little bleak at the moment but there is reason to hope.

Online and offline integration:

As online e-commerce traffic gradually slows down, there is a growing realization that brick and mortar stores where people can see and touch the products are an essential part of the consumer experience. As a result, online and offline integration is fast emerging as an important new trend pushed by the need to give consumers a pleasurable shopping experience in order to maintain their loyalty. This presents an opportunity for traditional supermarkets to totally revamp their existing stores into operations that are consumer-centric, data-driven, and which integrate both online and offline experience in terms of product offerings and marketing strategy to garner consumer loyalty. Both Costco and ALDI have opened their first China stores only after several years of testing the market through online e-commerce platforms which gave them numerous insights into Chinese consumer behavior. We also find that in China ALDI has transformed its usual store into a new type of supermarket on the lines of its local competitor, Hema Fresh stores, privileging online shopping, in-store catering and grocery delivery services.

M&A and strategic transformation:

From the examples of Wal-Mart and ALDI, we can observe that some foreign retailers are still optimistic about the potential of the Chinese market and are using the mergers to transform their business models to become more localized and digital. That both Metro and Carrefour chose Suning and WuMart, Chinese companies that have the same traditional offline business model as they do, indicates that the two companies are not nostalgic for the old days. On the contrary, they are using the mergers as an opportunity to make a successful digital transformation in their Chinese business.

Technology

Can AI chips `save’ China’s semiconductor industry?

China has proved itself to be quite innovative in many industries. For instance, it is self-sufficient in nuclear power generation and is in the forefront of many areas of artificial intelligence (AI). But when it comes to semiconductor production, China remains woefully behind, spending more dollars on imports of semiconductor chips than on crude oil. Last year alone, China imported US$312 billion worth of chips to meet domestic demand.

The Chinese semiconductor industry

Semiconductor chip design and production is universally known as a notoriously complex business, involving decades of expertise and extreme precision – a slight miscue and billions of dollars of investment can go up in smoke. Yet, in the beginning, China was in the forefront of IC development. Integrated Circuits (ICs for short) were first invented in 1957 and three years later, they were successfully commercialized in the US. Just eight years later, in 1965, China managed to create its own ICs, placing it well ahead of would-be competitors such as South Korea, who has not started developing a semiconductor industry at the time.

However, 50 years later, China got left behind and now trails behind the US and South Korea in semiconductor technology. After several decades and billions of dollars of investment, China manufactures only 16 percent of the total semiconductors used in China today. Moreover, though the government has long been aware of the need to develop a strong semiconductor industry of its own, no serious action was taken because it was simply much easier to import what was needed as cutting edge technology in the field becomes obsolete every two years. However, as the ongoing trade war with the US has shown, this lacuna could be fatal as the US could easily cut off critical access to US components for China’s fledgling tech champions. Thus, the need to develop an indigenous semiconductor industry has become infused with urgency. But, given the high rate of obsolescence in the semiconductor industry, analysts estimate that it may take China a decade at least before it can be on par with its rivals.

Why did the Chinese semiconductor industry fall behind?

In the early years of the development of the global semiconductor industry, China simply did not have the talent or the know-how to develop semiconductor manufacturing technologies domestically. Then, in 2014, China established the China National Integrated Circuit Industry Investment Fund (also known as the Big Fund), raising RMB 14 billion for investment in China’s semiconductor firms. As a result, there was a frenzy of semiconductor lab building across China. But, despite the avalanche of money, China still does not have a significant portfolio of intellectual property in integrated circuits. For the truth is, equipment is only one of the necessary conditions for the development of a semiconductor industry, human capital and experience play equally, if not more important, roles.

The IC industry is hugely talent-intensive, from architectural design to coding, especially in the upstream technical design stage. Glitches in design and conception of ICs can result in a huge and costly waste of resources downstream. Hence, talent and experience are essential to developing the semiconductor industry. But because China was blindsided by the idea that all it takes is labs and equipment to produce a new generation of technology for the fabrication of semiconductors, they over-emphasized the importance of investment in equipment and under-emphasized the importance of investment in human capital.

Another contributing factor was the lack of motivation to develop core technologies. The long cycle of investment returns from IC productions pushes some companies, in the face of market zeal for ICs, to chase short-term revenues without doing the hard work to develop core technologies. For a long time, companies and government agencies made the biggest margins from labor-intensive industries such as product assembling. However, the production of ICs requires initial investments in the hundreds of millions of dollars which will possibly not be recouped for at least ten years. Not until recently did China have an adequate amount of capital to fund the research and design of IC production but funding itself is not enough to make up for lost time.

AI Chips: A silver lining in China’s semiconductor industry

Nowadays, artificial intelligence chips play a pivotal role in the Chinese semiconductor industry. AI chips are dedicated chips used for processing data for AI applications. These chips differ from general-purpose chips in the sense that they rely mainly on algorithms and standards and thus are less subject to Moore's Law, i.e. that the performance (speed) of integrated circuits must be doubled every two years. For AI chips, the algorithm model for processing data is more important than the operating performance of the integrated circuit itself. As China's general-purpose chip manufacturing capability lags behind that of advanced countries, AI chip design provides Chinese semiconductor manufacturers with a golden opportunity to get ahead of the game by developing better algorithms. This may ultimately become China's trump card for leapfrogging into the semiconductor manufacturing industry.

Thus far, many Chinese companies have been working on the development of AI chipsets, covering applications as diverse as driverless vehicles and the Internet of Things. In the field of AI chip development, China has already surpassed some American companies. Government support, a large user base and the gradual commercialization of AI application products, makes success in the AI chip production’s algorithm optimization a very real possibility. Once that is done, given the hectic speed at which the Chinese AI chip market is growing, becoming profitable will not be difficult.

However, China’s AI champions took a major hit last week after the US added eight of them to a trade blacklist, preventing them from buying US technology. Although these companies claimed they have domestic alternatives, in reality it is not easy to source alternatives for the hardware that the AI software relies on, such as sensors, GPUs (Graphic Processing Unit), FPGAs (Field Programming Array) and chipset design software.

As of 2019, China had only one company among the top 15 for semiconductor sales globally while the European Union has two and the US six. But if we look at the number of firms designing AI chips, the gap narrows — the US has 55, followed by China with 26. The EU is in third place with 12 firms. Thus, China still has a good chance to catch up in the field of AI chip design.

Life Science & Healthcare

The best way to succeed under '4+7' extension?

On September 30th, the central government announced that the VBP (volume-based procurement) program would launch nationwide, covering the sale of 25 drugs at all public health care institutes. The decision was taken after about 6 months of a pilot operation of VBP in 4+7 cities. With the fierce bidding process bringing prices of some drugs down to the fire-sale level, pharmaceutical companies are going to find their profits squeezed, SG&A expenditure reduced and rumours about sales & marketing department cuts. Pharmaceutical companies are asking themselves where to go next and how best to succeed in the new environment.

VBP program launches from Pilot 4+7 cities to nationwide expansion

Last November, the Chinese government published a paper called the "National Drug Centralized Procurement Organization Pilot Scheme" which put in motion a new Volume Based Procurement scheme for 25 drugs in 4 pilot Municipalities and 7 provincial capital cities, '4+7' in short. The scheme was launched in order to reduce expenses in healthcare. Formal implementation of the program began in Mar 2019 and, according to government data, the pilot scheme accomplished its goal of curtailing medical insurance expenditure. Moreover, VBP winners clinched 78% of the total purchases of these 25 drugs in 4+7 trial cities. In Shanghai alone, savings by patients from VBP winner drugs totalled RMB1.20 billion. In the 4+7 trial cities, VBP winners increased their sales sevenfold. Even after taking into account the price reduction, VBP winners nearly doubled their revenues — in sharp contrast to VBP losers whose sales plummeted.

In order to level the price gap between pilot and non-pilot cities and to bring the benefits of the scheme to more people across the country, the central government decided to increase the reach of the VBP program, making it nationwide. To avoid supply shortages during 4+7 trial period due to insufficient production capability and price increases of API (Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients), the government now allows multiple winners for nationwide VBP biddings, with a detailed stipulation on procurement volumes and the number of winners. This time around, more MPCs (multinational pharmaceutical companies) jumped into the bidding process and surprisingly, the final VBP winning bids were priced on an average at 25% less than the average price during the 4+7 pilot trial, and 59% less than the lowest average winning bids in 2018 before the VBP program. Under centralized VBP practice, sales team or marketing promotion is hardly necessary, thus SG&A (selling, general and administrative) expenditure of VBP winners were all but non-existent and with fierce price-cut, profit margins also shrank further.

Besides Hebei and Fujian provinces which initiated their own programs based on the 4+7 pilot program early this year, as of October 18, eight provinces had plans in place to implement VBP programs and other provinces are expected to do the same soon. In addition to penalties for failing to reach VBP volume targets by hospitals and doctors, these eight provinces also put in place incentive policies to reward successes: surplus contributed by switching to VBP drugs can be retained for bonuses to health care professionals, local government won't call down hospital annual expenditure target, namely, though using VBP will save a lot expense for hospitals, the government won't call down hospitals' annual expenditure target, leaving room for other drugs overspend. Moreover, these provinces also emphasized the importance of supply stability and drug quality and companies that failed in these requirements, they stated, would be excluded from future VBP programs on both drugs and medical consumables. Provinces also came out with policies to address the medical insurance payment consistency issue as well as instituting a gradient price reduction mechanism for VBP losers including brand drugs which would enable them to reach the VBP winner price level within a 2 to 3 year timeframe. Guangdong has gone even further - setting a detailed annual price reduction target for VBP loser drugs.

Where to head under VBP policy?

As a key strategy of healthcare reform, VBP will continue to reshape the pharmaceutical industry. The government will keep pushing for greater standardization, concentration and innovation in the pharmaceutical industry with initiatives such as GQCE (generic quality consistency evaluation) which started three years ago and the VBP pilot which was introduced last year. Although the current VBP only covered 25 drugs, we can safely predict that in the future the VBP program will expand to all ATCs (Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical Classification drugs). To adapt to the trend, pharmaceutical companies need to streamline and re-evaluate all aspects of their operations, and especially to critically re-examine their organizational structures, R&D pipelines and commercial strategy.

Brand drug manufacturers should be considering how best to make off-patent / near-off-patent drug spin-offs. For these drugs, investing more on a commercial supply team, government affair team and bidding team should take priority over traditional sales & marketing teams. To ensure a continuous market presence, they should also consider developing generic versions of their own branded drugs which only have a short remaining patent protection period. The earlier this reform takes place, the more success they can expect in the future as the government is determined to push prices lower given how popular the VBP scheme has been.

Generic manufacturers, if they are to survive in the new environment, need to pass the GQCE (generic quality consistency evaluation) as soon as possible. As of now though, of all the 289 drugs on the essential drug list (EDL), only 53 have generics that passed the GQCE. Moreover, the GQCE has now become an essential part of the VBP selection process. In current VBP bidding, only the first 3 companies that passed the GQCE were eligible to participate in the bidding. Moreover, manufacturers should consider investing in in-house API production to ensure quality control and a stable supply of drugs. In general, pharmaceutical companies across the board need to pay greater attention to their product pipelines than ever before as a profound, innovative drug pipeline will be the key to sustainable growth in the future.

The old methods that Pharma companies used to deal with competition, namely erecting technical and manufacturing barriers for generic companies during the research and development phase, are not going to be very successful with governments eager to get high quality healthcare to the people at the lowest possible prices. Pharmaceutical companies need to pay especial attention to current health care economics and policy trends. For example, a window of opportunity has just opened in the area of critical and rare diseases care.

China has made considerable strides in building a comprehensive primary healthcare system through most of the country but there still remains an urgent need for better facilities for critical diseases and rare diseases. To address this issue, the Chinese government announced a series of regulatory reforms aiming at accelerating the process of making available on the market the latest medical innovations. These include a fast-track approval process and a potential local-study waiver for products targeting rare diseases or diseases with substantial unmet needs. While relying on their own strengths and capabilities, pharmaceutical companies should also take advantage of these policies as they plan their future drug pipelines.