Perspectives

The Deloitte Research Monthly Outlook and Perspectives

Issue LVI

24 April 2020

Economy

Can China lead a regional recovery?

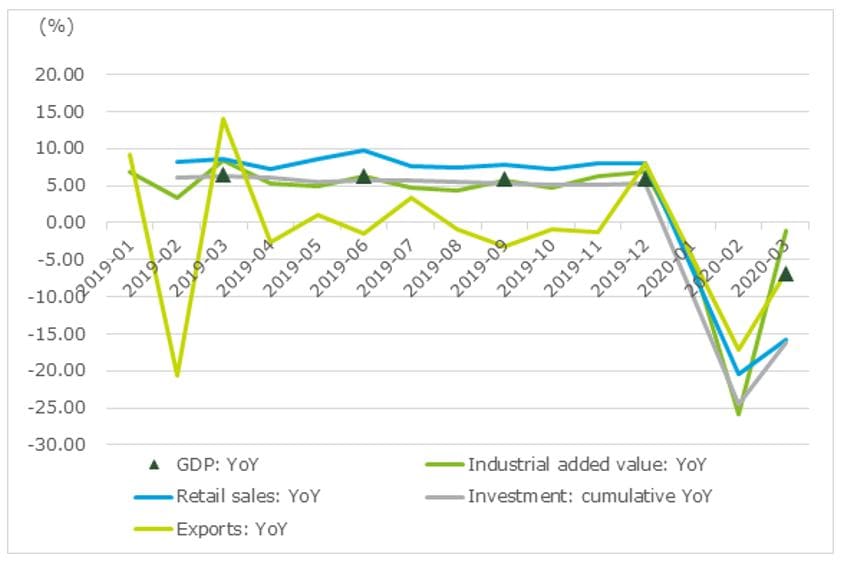

How sharply did the economy contract in Q1 when almost the entire country was under lockdown? This question has been weighing on the minds of investors in particular, and China watchers more generally, since late January. Their anxiety has been heightened by the knowledge that the Chinese economy has been showing signs of a slowdown for the past few years while leverage remains high, with debt/GDP around 267% in 2019. But today’s Q1 GDP growth figures which came in at -6.8 percent should have alleviated at least the worst of their fears —especially in light of the near total shutdown of economic activity in China and other major economies.

In recent publications, we projected a contraction of 7-8 percent based on our observation of economic activity in January and February. We also forecasted a flat Q2 and a vigorous recovery in 2H (around 7-8 percent). The Q1 GDP growth figures have reinforced our long-held view that China's consumer resilience is underpinned by certain solid structural factors (e.g., high savings rates and low consumer debt leverage). If growth in the second half of the year (2H) is around 8 percent or even higher, GDP growth in 2020 could hit the upper limit of our forecast range of 3-3.5 percent.

Chart: Green shoots of China in the midst of outbreak

China's March trade data has brought a surprise glimpse of recovery: Q1 trade only fell by about 6 percent, rather remarkable considering that Wuhan was shut down on January 23 and the entire country has gone through various degree of mobility restrictions, some of which are still ongoing. It is also important to highlight the fact that the RMB has strengthened based on PBOC's currency basket this year, and this is despite the overwhelming strength of the greenback caused by global cash hoarding.

So what are the lessons to be learnt from China's Q1 trade performance?

Though it is still a little early to extrapolate because several major European economies are still severely affected by lockdowns, what we can see quite clearly is that regional trade is playing an increasingly important role in holding up the figures. For example, Vietnam has replaced several industrial economies as one of China's major export markets. In the short run, assuming that the economic recovery in North America and the EU will trail China's by a couple of quarters, China's demand for intermediate goods from its neighbors could lend some cushion. And finally, China's booming trade with Vietnam, who has become a winner thanks to the reconfigured global trade arrangements, fits our hypothesis of production migration from China to other low cost producers.

Chart: Thriving intra-regional trade lends support to recovery for the time being

Share of China's top 5 exports markets

Share of China's top 5 imports sources

China’s economy will recover strongly later this year, a welcome boost for the rest of Asia

A slew of sector-wise Q1 economic data released on April 17 by the National Bureau of Statistics enables us to get a truer picture of how the Chinese economy has been affected by the coronavirus epidemic. Total retail sales of consumer goods saw a 19 percent reduction in Q1, with consumer staples and physical merchandise online sales bucking the trend. Q1 fixed asset investment dropped by 16.1 percent as expected, but the investment in e-commerce and professional technological services have taken off. Trade volume lowered by 6.4 percent in Q1, with exports bearing the brunt of the contraction (-13.3 percent) while imports scraped by with only a -2.9 percent contraction, and the thriving intra-regional trade have helped to brought a surprise glimpse of recovery in March. The housing market also seems to have weathered the storm. Housing prices in 70 cities have risen 5.4% yoy in March 2020, with second-hand housing prices in Shenzhen seeing an exceptional gain of 9.7% yoy.

China’s economy will remain sluggish in Q2 2020 as February's sizeable uptick in unemployment to 6.2 percent (which inched back to 5.9 percent in March) weighs on household sentiment and thus private consumption. Additionally, although the People's Bank of China has lowered the cost and expanded the quantity of credit to the real economy, banks have not passed all of this on to the areas of the economy that have been hit hardest— small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) in the private sector. We cannot, therefore, expect much from growth in the first half of this year.

However, the Chinese economy should recover strongly in the second half provided the COVID-19 infection curves flatten in the US and western Europe by late Q2, and as capacity utilization returns to normal and a bigger-than-expected stimulus package lends a fillip to growth. With Chinese policymakers now averse to the type of large, "flood irrigation" type stimulus that was deployed in 2008, we think the fiscal stimulus to be announced shortly will be more efficiently deployed and could therefore be enough to drive GDP growth above 3 percent for 2020 as a whole.

Given the above, our base case is for a substantial acceleration in China’s economic growth in the second half of this year. Again, our assumption is that, barring a resurgence of COVID-19, the recovery of major developed countries will lag behind China's recovery by around two quarters.

Other Asian economies will be buoyed by monetary interventions and fiscal policies

Bold responses in other Asian economies will also help produce a stronger second half of the year in the region. Asian governments have announced wide-ranging monetary and fiscal interventions to cushion the worst of the pandemic's effects and prevent a downward spiral in economic conditions. Monetary authorities have responded forcefully via large rate cuts, using off-scheduled meetings where necessary. They have also gone beyond the traditional playbook of rate cuts and liquidity support to banks. On the fiscal side, governments have grasped that fiscal policy will have to do the heavy lifting in supporting growth, given the precipitous fall in global demand — upon which their export driven economies rely.

In light of these measures, we expect that a very weak first half of the year is likely to be followed by a strong second half, laying the foundations for a vigorous revival of economic dynamism in 2021.

The big downside risk: could financial stresses become 'crystallized' even if broad aggregate demand eventually recovers? If so, who is most at risk?

The COVID-19 shock led to a severe “sudden stop” in capital flows to emerging markets. According to the Institute of International Finance, outflows in Q1 2020 alone reached US$83.3 billion —much larger than during the peak of the 2008 global financial crisis—and emerging Asian economies took the hardest hit.

Despite these countries’ central banks’ Herculean attempts to provide unprecedented liquidity support to markets, the sharp rise in the US LIBOR-OIS spread, a key gauge of banking sector risk, shows that financial stress remains elevated. Further bouts of financial turbulence are likely, which will adversely affect Asian economies.

The region’s currencies, equities, and bonds have already received a drubbing, but further declines are likely in the present `risk averse’ climate— especially given their status as riskier parts of the investable universe. Yield differentials vis-à-vis developed markets have narrowed as the G3 central banks applied maximum monetary stimulus, but this will bring little relief for Asian assets, which are more sensitive to growth wobbles.

A global rush into safe haven currencies has pushed the value of the dollar to vertiginous heights, making it more difficult for emerging Asian economies to service their stock dollar-denominated debt. Most emerging Asian economies are exposed: China (5.5 percent of GDP), Korea (14.0 percent of GDP), India (5.1 percent of GDP), Indonesia (7.2 percent of GDP), Malaysia (8.1 percent of GDP), and Thailand (5.8 percent of GDP).

The maturity profile of Asian non-financing corporate debt shows a large chunk of bonds are due for repayment in 12 months or before. This is especially salient because refinancing will be more difficult than in previous years given the current risk averse market conditions which are likely to persist through most of 2020.

Domestic stability could also be threatened as a toxic mix of sharply slowing growth, tightening financial conditions, and existing high leverage in some jurisdictions amplifies the economic damage to come, putting banking sector stability to the test. According to the International Monetary Fund, 40 percent of total corporate debt, or US$19 trillion , would not be serviceable even in a recession half as severe as the financial crisis in 2009.

Non-financial corporate debt levels look large in Hong Kong (219 percent of GDP), Korea (151.1 percent), China (153.6 percent) and Singapore (97.9 percent) . Household debt levels are elevated and form a large share of total private non-financial sector credit in Vietnam, Thailand, and Malaysia, suggesting increased risk of a debt crisis in the household sector. A recession in property prices is also possible, which will further weaken the financial position of households, as a large chunk of their debt is typically in mortgage loans.

The absolute level of leverage is not the only factor in play. Equally important is the ability to service that debt, although we highlight the risk that income streams could evaporate quickly in a severe economic contraction. Looking at debt servicing ratios and absolute leverage levels in tandem alters the picture, as high debt levels in Hong Kong and Korea are balanced by very high debt-service ratios. This leaves Malaysia and Thailand as the economies most at risk.

A threat to the banking system can emerge out of a conjunction of three conditions: sharply slowing growth, tightening financial conditions, and existing high leverage in some jurisdictions that amplifies the economic damage. The presence of even two of the three conditions can put banking systems to the test. Countries like Vietnam, who have an under-reporting of non-performing loans and thinly spread credit, are the most vulnerable.

Conclusion

Assuming that the worst of the COVID-19 crisis will be over in the key economic powerhouses of North America and western Europe by the early part of Q3 2020, and given the further boost from aggressive, broad-based countercyclical measures, we expect that the Asia-Pacific economies, led by China, will begin to make a recovery sometime in the third quarter. However, downside risks still remain. In addition to the potential for financial sector instability described above, a renewed trade war is possible since it is unlikely that China can deliver on its promises to buy more US goods (an additional US$200 billion in 2020 and 2021) at present. Even in the absence of a trade war, trade tensions between China and the United States could well be a long-term theme that is further complicated by domestic politics in both countries and the geopolitical overlay.

Technology

"New infrastructure" to boost digital economy

Demand-side risk is growing

In the past month, supply side risks have eased as most factories in China have resumed operation. As tele-conferencing applications and mobile office tools continue to gain traction with businesses, increased time on video portals and online gaming has resulted in a surge of network traffic and bandwidth use. The industry has also seen a rising demand for chips used by cloud and data centers. However, risk is now shifting to the demand side as smartphone and consumer electronics sales fell catastrophically during the pandemic lockdowns around the world. Global smartphone shipments dropped 38% in February to 61.8 million devices, the largest drop ever in the history of the smartphone market and the fall is expected to continue into Q2.

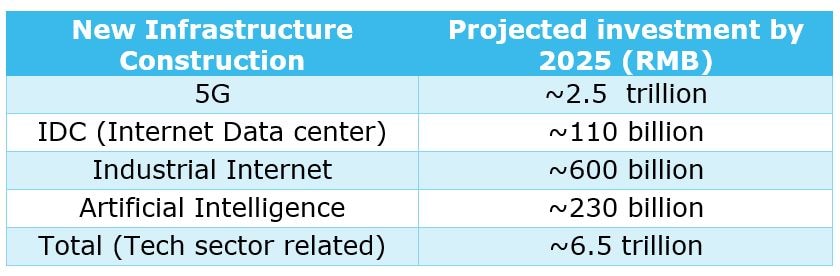

Stimulus measures to boost tech infrastructure

Since the beginning of this year, the term "New Infrastructure” has worked its way into the work reports of the Guangdong, Chongqing and Hunan provincial governments, as well as those of Beijing and other cities. “New Infrastructure” generally refers to the infrastructure for high-tech which includes areas such as 5G, artificial intelligence, industrial Internet and data centers. While these policy measures are not specifically targeting the demand side, they are still poised to give the economy a boost while providing building blocks for a high-tech driven economic model in the future. “New Infrastructure” entails facilities that serve the needs of a technology driven industrialization, as opposed to the traditional infrastructure construction driven industrialization that China has known thus far.

Chart: Projected new infrastructure investment relevant to tech sector

5G – Peak construction in next two years

5G is the key component of all new infrastructure construction as it paves the way for the development of other areas of new technology such as AI and the Industrial Internet. 5G is also a crucial part of China’s plans to take the lead in the world in connectivity technology. This year and the next will be crucial in terms of investment in 5G, and operators' capital expenditure will gradually increase to create a commercial 5G network covering the whole country. The rapid expansion of the 5G network will popularize 5G business applications, which will lead to an acceleration in the growth of data traffic, thus increasing the demand for data centres and cloud computing services.

The Industrial Internet will also benefit from the rapid development of 5G, with accelerated growth in typical applications represented by the Internet of Things, Internet of Vehicles, industrial production and remote services. The commercialization of 5G will also promote the growth of the cloud computing industry as cloud service providers are expected to carry out a new round of equipment expansion while telecom operators are also planning to purchase servers in response to the 5G era of data services. Overall, starting in 2020 and over the next 3 to 5 years, China's server industry is set to boom.

Internet Data Centers - Ample room to grow

Compared with the United States which has 44% of the world's data centers, China has less than 20%. Hence there is still much room for improvement. The development of emerging industries depends on data resources. Therefore, from the national government to major industries, the build-up of data centers with Internet data centers (IDC) being the most crucial, is imperative, as this will help promote the transformation of industry and help enterprises' migrate onto the cloud. IDC has benefited significantly from the explosive increase in network traffic during the COVID-19 lockdown. As people spend much more time online watching videos, playing games and shopping, it is expected that the number of domestic data center projects will increase rapidly, especially large data centers. As existing policy restrictions will hold back growth in Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou and Shenzhen, investment in data centre construction will most likely take place outside the tier-one cities. Regions with favourable electricity rates and abundant land resources such as the northwest and southwest parts of China have a good growth potential. According to China Telecom, the rack number of national IDC in 2018 was 2.034 million. This is expected to grow to 3.367 million by 2020. The expansion of data centers also directly drives up the demand for servers, storage, networks and security products.

AI – AI chip key to proliferation of applications

The penetration of artificial intelligence(AI) technology is increasing in areas ranging from transportation, finance and government affairs to education and agriculture. As demand for AI applications in business increases, their scale will also grow. In 2020, the scale of the AI market in China is expected to expand by 45%, far exceeding that of the global market. However, the development of AI chip technology is inseparable from the spread of AI technology. Existing chip makers are not the only players in the market to ramp up their research and development capacities. Several new AI start-ups and technology companies are also are rushing into the field to grab a piece of the pie. Neither governments nor companies want to miss out on the crucial opportunity of developing better and faster AI chips. As the cornerstone of commercialization and technology innovation, it is inevitable that the AI chip will be developed and commercialised on a large scale in the future.

Industrial Internet - Entering the fast track

The Industrial Internet is an intelligent digital network system that unites industrial big data and machines to dramatically improve the speed and efficiency of manufacturing. It can intelligently extract the basic data of the manufacturing industry and produce industrial automation products which improve the manufacturing process. According to the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology’s (MIIT), 2025 is earmarked for the construction of Industrial Internet infrastructure and platforms. The list of pilot projects includes 81 demonstration projects, covering fields as diverse as large aircraft manufacturing, electrical equipment manufacturing, port management and equipment processing.

Many hurdles still to be cleared

Previously, China's stimulus spending gave a much a larger role to State-owned enterprises (SOEs) and major construction projects. However, for the New Infrastructure project, of the entities that specialize in these sectors, almost all are non-SOEs - such as Alibaba, Tencent, and Baidu, as well as other start-ups. How the investment funds are distributed among these enterprises and how these projects can achieve both public and private goals will be a complex issue that needs to be addressed. Furthermore, the return on investment in the new infrastructure sector has many uncertainties since these technologies are fairly new and untried. It may well take years to recoup one’s investment here as opposed to the comparatively quick and easily quantifiable returns one can expect with simpler physical infrastructure projects.

Automotive

Export woes and another supply chain choke point

Since March, as the Covid-19 pandemic intensified in Europe and North America, social activities have come to a grinding halt. Factories have been shuttered and people asked to stay at home. This has led to a precipitous fall in consumption, and future investment decisions have been put on hold or cancelled. The collapse of overseas demand has had a ripple effect in China as well as other emerging Asian countries.

In less than two months, Chinese auto parts suppliers were hit with a double whammy from overseas clients: demands for compensation for failure to deliver goods due to factory lockdowns in January and February and requests for delayed shipment and payment delays in March. If the pandemic drags on in Europe and the United States, the auto industry in China is faced with the possibility of a second shock from overseas demand destruction and shortage of spare parts. Worse still, some multinational manufacturers have already looked for substitutes during the outbreak and now contemplate rebuilding their supply chains in a way that decouples them from China.

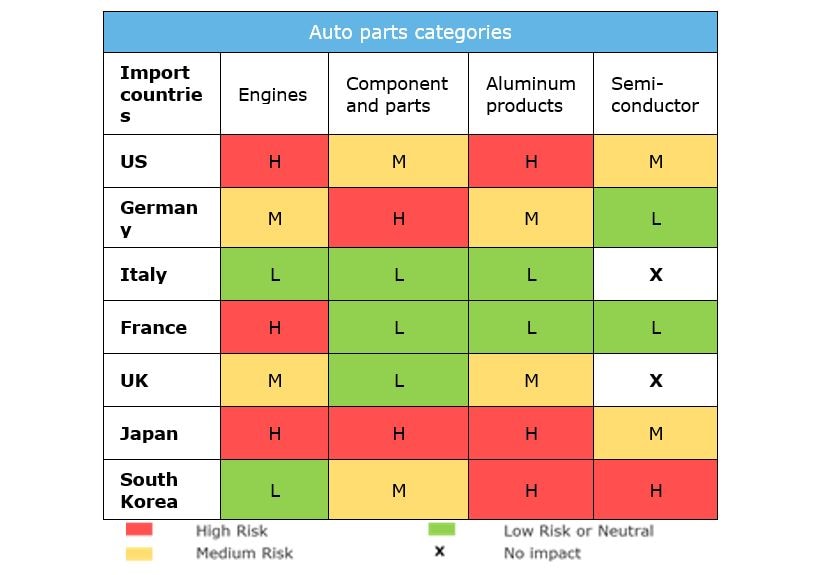

In the last Monthly, we looked at the impact of China’s lockdown on automotive manufacturing around the world, given that China accounts for almost 50% of manufacturing output worldwide and provides 10% of global intermediates production. In this issue, we will look at the impact on China and the significance of global interdependence. Though China is recovering from the pandemic, it cannot survive alone.

Auto parts is one of the economic sectors that bears the brunt of the global pandemic. China’s auto parts manufacturing exceeded RMB 4 trillion in sales revenue in 2019, with exports reaching RMB 374.4 billion (about $53 billion) in goods value. America is the number one export destination (26%), followed by Japan (11%), South Korea (6%) and Germany (4%). The majority of China’s auto parts exports are low-skilled, labor-intensive products such as bumpers, brake pads, clutches, wire-harnesses and so on. A prolonged pandemic will exact a heavy toll on export-oriented businesses.

When the pandemic hit China, foreign automakers turned to Vietnam for substitutes. Production was easy to shift as labor costs are a major consideration for any labor-intensive good and labor costs in Vietnam are lower than in China. Therefore, it is only natural to ask the question - “will multinational companies ever return to China after the coronavirus epidemic ends”? We tend to argue that it takes a long and thorough process for any supplier to be approved and get onto an auto OEM’s supplier list. Chinese parts manufacturers have proved their value in product quality, reliability and efficiency in logistics for the last few years. Therefore, in the short to medium term, MNCs are likely to honor their contracts with Chinese suppliers. But in the long term, the coronavirus pandemic might lead to a reshuffle in many MNCs’ Asian supply chain. Japan appears to be the first to make such a move. In its record economic stimulus package announced on April 7th, the Japanese government allocates $2.2 billion to help manufacturers shift production out of China by moving high value-added goods back to Japan and other production to countries across Southeast Asia.

The other place where the coronavirus has had an impact is the domestic car manufacturing front. As important as China’s role is to global vehicle production, the country also depends on imported raw material and intermediates to finish the final assembly of vehicles meant for China. For instance, to meet the growing demand of in-vehicle connectivity and autonomous driving functions, Chinese carmakers import automotive semiconductors from outside the country. Multinational car companies also still rely on imports of auto parts (about 40% of parts imports are from the US, Germany and Italy) for cars sold domestically, despite their efforts to increase local content in recent years. Some auto OEMs insist on importing key parts, such as engines and transmissions from factories overseas. That practice has made a lot of MNCs with low localization rates in China more susceptible to supply chain disruptions. The additional costs incurred due to shortage of parts also make automakers more reluctant to slash prices, further weighing on fragile consumer confidence.

Chart: China’s exposure to global auto parts supply chain disruption

Life science and healthcare

After Covid-19, China’s pharmaceutical industry faces many uncertainties

On April 5 local time, the World Health Organization (WHO) announced, in its 76th COVID-19 situation report that China has moved from "containment stage "to" mitigation stage". In many ways, the pharmaceuticals industry was at the heart of the battle against COVID-19. However, the pandemic has brought a lot of uncertainty to China's pharmaceutical industry.

Behind the surging demand for COVID-19 related products lies the need for an industry upgrade

As China's epidemic situation improves and the situation in other countries worsens, overseas demand for COVID-19-related medical supplies is surging. As production capacity returns and upstream and downstream enterprises resume operations, pharmaceutical manufacturers are now able to move full steam ahead. The Joint Prevention and Control Mechanism of the State Council announced at a press conference on April 5 that China exported RMB 10.2 billion worth of COVID-19 prevention and control products, including about 3.86 billion masks worth of RMB 7.7 billion from March 1 to April 4 (compared to around 3.5 billion for the entire year in 2019), 37 million units of protective clothing worth RMB 910 million, 2.4 million infrared thermometers worth RMB 330 million, 16,000 ventilators worth RMB 310 million, 2.84 million testing kits and 8.4 million pairs of goggles. The manufacturers of these items have experienced explosive growth mainly because of the pandemic. However, most of the surge in exports comes from relatively low value added goods with a low technology barrier. In the field of ventilators, which have relatively high technology barriers, local manufacturers rely on upstream imported parts such as compressors, sensors, and chips. This is also the main reason why local manufacturers cannot meet high overseas demand. In addition, local ventilator manufacturers mainly focus on mid- to low-end ventilator products, as the high-end of the market remains dominated by multinationals such as GE, Philips and others.

Figure. Ventilator value chain

At present, the domestic content of high-end medical equipment is low - with a less than 30% localization rate in ultrasound and CT products, less than 15% in MRI units and less than 10% localization rate in endoscopy and digital subtraction angiography (DSA) units. In response, the government has been supporting medical device core technology research and development. On March 2, President Xi Jinping stressed the need to enhance China's capability in high-end medical equipment production, speed up core technology research, break through the choke points of technical equipment manufacture, and achieve a high degree of independence in the manufacturing of high-end medical equipment. In the coming years, the government will introduce more relevant policies to support these aims. Local enterprises should take advantage of the favorable policy environment to accelerate investment in scientific research and industrial upgrading.

Clinical trial suspension affects new drug launches in the next two years

During the epidemic, more than 70% of the clinical trials in China were affected. In Hubei, almost all of the clinical trials, except for COVID-19 clinical trials, were suspended. In Wuhan, it is estimated that the drop off rate of clinical study is more than 70%, and it may be as high as 50% outside Wuhan. There are many reasons for this. For example, a clinician was dispatched to Hubei in the fight against the virus and could not continue the trial; a subject involuntarily dropped out because of imposition of travel restrictions and a clinical coordinator who needed to work across provinces could not maintain a normal work schedule due to the 14-day isolation order.

The most direct impact of clinical trial suspension is the delay in the expected launch of new drugs by at least 3 months, 6 months or longer. This has many repercussions: it reduces the period of time during which profits can be made for a drug under patent protection, and it also makes pharmaceutical enterprises lose the opportunity to build up market share as early as possible.

In addition, the suspension of testing also increases cash flow pressures for CROs (Contract Research Organizations), SMOs (Site Management Organizations), and Pharmaceutical enterprises. CROs and SMOs, as the undertakers of clinical trials, are the most directly affected parties. In general, their services are billed by the hour but during the suspension period, they cannot charge extra fees and yet they still need to pay their staff - especially CRCs (clinical research coordinators), CRAs (clinical research assistants) – or risk losing them to competitors. This puts increasing pressure on their cash reserves as the months go by. Cash flow pressure on pharmaceutical enterprises is indirect, mainly due to the longer time horizon it takes to recoup their investment as a result of delay in drug launches. To some extent, the financial support provided by the central government such as preferential tax policies for resumption of production, special loans and so on has helped to support affected pharmaceutical enterprises.

As China's COVID 19 lockdown eases, clinical trials and multi-regional clinical trials that include China have gradually resumed. But with the continued spread of the Coronavirus to many other parts of the world, Chinese enterprises have had to suspend numerous overseas clinical trials, thereby delaying the process of overseas drug launches. Thus, the coronavirus has effectively created a new barrier for large and medium-sized drug enterprises to explore the overseas market. At the same time, the pandemic has, however inadvertently, also created opportunities for CDMO (contract development and manufacturing organization) companies in China, and these have undertaken more overseas orders thanks to the virus.

Global API supply chain will be reshaped gradually

In the past 10 years, many western countries have divested production capacity of low profit, highly polluting APIs (Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients) to places like China and India that have a technically capable API industry with low labor costs, relatively more relaxed environmental requirements and the benefit of economies of scale in mass production. They then imported these outsourced APIs and focused on producing finished products with higher profit margins domestically. This is how China came to account for 28% of global API capacity, making it the largest supplier of APIs in the world.

During the outbreak in China, API production stopped as a result of the lockdown and countries such as the United States were in danger of having their supply of certain drugs such as antibiotics (and other generic drugs produced in India) completely cut off. In tandem with the changing international policy environment over the last two years, many countries have decided to gradually reduce their dependence on overseas API supply, especially vis-a-vis China, and diversify API supply countries in order to reduce the risk of supply disruptions. Considering the production capacity construction cycle and high labour costs involved, API production capacity will not be easily transferred from China in the near future. However, in 3-5 years time, China's API exports will probably decline sharply or even go into negative growth. China's API manufacturers need to plan ahead to meet these challenges, such as working more closely with local pharmaceutical manufacturers to cope with the benefits of volume-based procurement, improve the production capacity of finished drugs, and/or cooperate with foreign API manufacturers through mergers and acquisitions to meet future challenges.

Energy

Oil & Gas: coping with price volatility

The current collapse in oil prices is very different from 2008 in terms of causes and supply/demand patterns. This time around, oil companies will need to minimize expenditure to ensure business continuity while protecting the value of core assets to prepare for the market return.

Double whammy

At present the oil market telling from the ‘double whammy’ of flagging demand and price collapse. Stagnant economic growth, combined with the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic has crushed oil demand completely. And, with Saudi Arabia and Russia disagreeing on production cuts, it has triggered a price war, further depressing prices in March.

On 12 April, OPEC+ finally agreed to cut output by 9.7 million barrels a day for May and June, followed by a slow increase in production until the end of April 2022. Unfortunately the deal may have come too late and wasn't enough to change market sentiment. Oil prices have actually dropped since the finalisation of the agreement.

Figure: Inherent volatility (WTI, US$ per barrel, adjusted for inflation)

2008 Deja Vu?

Some hold the view that the current oil crisis is a repeat of the 2008 crisis but will also be long lasting. This view, however, ignores the fundamental difference between the current downturn and the 2008/9 crisis.

The origins of the current oil price collapse can be traced to a fall in demand and excess in supply. The 2008 crisis, by contrast, was caused by the collapse of financial institutions. Academic research reveals that a recession originating in the banking system tends to be more severe and last longer.

In 2008, both consumption and production took a hit as global markets dealt with a worldwide financial crisis. Oil prices dropped from a historic high of US$147 a barrel in July 2008 to US$33 per barrel in December, and then took nine months to stabilize by August 2009. World oil consumption fell 0.5 percent and 1.5 percent for two consecutive years - 2008 and 2009. However, this time we can hope for an economic recovery, and therefore an increase in oil demand in the second half of the year and world oil consumption should return to its pre-2020 level in 2021.

China, as the largest oil-importing country, is recovering from COVID-19 and hence the government has lifted bans on road, air and train travel. There is also a surge in crude processing, steel and construction activities. Industrial and Commercial Electricity Consumption increased with chemical, electronics sectors reaching 90% of normal consumption, and steel, machinery, and textile operations reaching 80% in March. Hence, demand for oil will pick up as China’s industrial production gets back on track.

Global trends in production and consumption, as well as the roles played by the world's major producers, have shifted. What the future holds is impossible to say for certain, but it will look different from what followed the 2008 crisis.

Looking ahead

Just as day follows night and night follows day, oil prices will raise again. According to the Short-Term Energy Outlook by EIA, crude oil prices will average US$33 a barrel for 2020 and US$46 a barrel in 2021. While there will be occasional surges towards US$60 and plunges to US$10. The low price environment will result from then interaction of the economic slowdown, environmental regulations, e.g. new shipping fuel requirements, and persistent oversupply (i.e. shale oil). For companies in the oil sector, adopting aggressive cost management programs, building resilience, and capturing restructuring opportunities are the key to preserving options for future growth.

Logistics

Crisis also brings opportunity

Global logistics network shock continues

With the spread of the global pandemic, many countries (and regions) have adopted restrictive measures one after another. Various factors such as the closure of countries and cities, the suspension of flights and ships, self isolation after border entry and other factors are all affecting the smooth operation of global logistics, which has led to rising global logistics costs, slower overall logistics timelines, and a major disruption of the global supply chain.

China's logistics industry gradually recovers

China has taken the lead in resuming logistics development. According to data released by the China Federation of Logistics and Purchasing on April 2, 2020, the prosperity index of China's logistics industry in March was 51.5%, up 25.3% from the previous month, and China's warehousing index was 52.7%, up 13.7% from the previous month. Moreover, both the new order index and the business activity expectation index have rebounded significantly. In particular, the business activity expectation index has rebounded to 58.1%, reflecting that companies are more optimistic about future expectations.

Chart: China Logistics Industry Prosperity Index (LPI)

Note: The logistics industry prosperity index LPI reflects the overall changes in the economic development of the logistics industry. 50% is used as the cut-off point of economic strength. Above 50%, it reflects the expansion of the logistics industry; below 50%, it reflects the shrink of the logistics industry.

The air cargo industry has continued to receive policy support. On April 2, 2020, the State Post Bureau and the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology jointly released a paper entitled "Opinions on Promoting the Deep Integration and Development of Express Delivery Industry and Manufacturing Industry". It proposes to support express delivery enterprises to build air express and freight hubs both domestically and abroad. According to information from the Civil Aviation Administration of China, China's international cargo flights increased 17.85% when compared with the pre-outbreak level, one week after the announcement of such policy measures as continuous reduction of international air cargo costs. The increase in air cargo capacity will benefit China's development of cross-border e-commerce and logistics.

China should seize the opportunity to restructure the global supply chain

At present, China has taken the lead in getting to the other side of the global pandemic. At this time, we should pay more attention to the consolidation of the global supply chain during and after the pandemic. We must strengthen trade cooperation and customs cooperation with countries around the world, especially the countries along the "Belt and Road" Initiative. And we should strive to remove barriers to international logistics channels to ensure smooth cross-border supply chains.

From the perspective of import and export trade, China also needs to accelerate the localization process of high value-added products and gradually increase the level of domestic industrial support. By supporting the development of domestic high-tech industries, a complete domestic industrial supply system can be created to protect the system from future shocks.

In restructuring the new supply chain model, three adjustments need to be made. One is the structural improvement of the supply chain, such as vigorously improving the state of procurement and the multi-point deployment of market supply to avoid single-source procurement. The second is to refine management of the supply chain. The third is the transparent upgrade of the end-to-end supply chain. These adjustments are inseparable from the digital and intelligent transformation of the supply chain, relying on big data and computer based technologies to reshape competitive advantage.

Retail

Consumer confidence key to a retail recovery

As the pandemic is gradually coming under control in China, retail businesses have resumed operations and the recovery is accelerating. Brick-and-mortar stores such as supermarkets, convenience stores and online shopping channels have gradually recovered from the crisis. By the end of March, 99.5% of supermarket chains and 95.4% of franchised convenience stores resumed operations, and sales exceeded the same period last year. For the sectors most affected by the pandemic (restaurants, travel and hospitality, luxury, fashion and department stores/shopping malls), it will take longer to get onto the path of recovery. By the end of March, while 95.8% of department stores resumed operations, sales were only 50% of last year’s.

Meanwhile, as COVID-19 continues to spread in US and Europe, Chinese luxury and outbound travel face the most severe pressure as consumer confidence is yet to be restored since consumers are still concerned about a second wave of virus spreading through China and the uncertainty of the situation overseas. On the supply side, the Chinese luxury market may see a sharp decline in revenue as the majority of luxury brands have halted production in Europe, and outbound travel restrictions will affect the sales of luxury goods in tax-free shops and boutiques.

Local governments introduced several supportive policies to speed up the recovery — for instance, cultivating and expanding new forms of consumption by developing online retail, services consumption, and promoting automobile consumption.

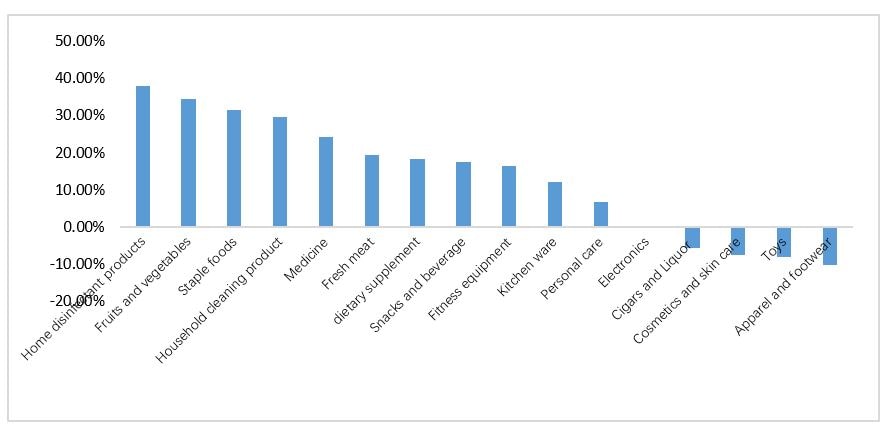

Changes in consumer behavior after the crisis

In the aftermath of COVID-19, Chinese households expect to see a decline in income and therefore consumer demand for discretionary goods will probably decrease as a result. Increasingly, demand for essentials is becoming the new normal. In addition, the lockdown has boosted Chinese online sales including B2C e-commerce and O2O on-demand delivery services. Consumers are willing to spend more time on online retail channels after the crisis.

Figure: Categories consumers prefer to increase purchase on after the crisis

In the post coronavirus future, consumers are more likely to choose more health, wellness and environmentally-conscious brands. Categories of products which bring about a sense of comfort and certainty to the consumer will see rapid growth, for instance, essentials such as food, beverages, and online games, which could help people cope with social distancing.

New trends for retail and consumer product brands.

Discount retailers may become stronger in the aftermath of COVID-19. Since the demand for discretionary goods like luxury and fashion products has decreased drastically, fashion and luxury goods will increasingly find their way into discount shops which are still appealing to consumers seeking value. Online or physical discount stores such as VIP.com will experience substantial growth after the crisis.

Live-streaming became a key shopping channel during the. COVID-19 crisis. Since home disinfectant products have become a necessity for Chinese households, personal care and household care brands will see new opportunities cropping up in the market. Key players should make more investment in innovation in aspects of product diversity and marketing strategies. For instance, implementing omni-channel strategies, creating a private domain traffic pool, and embracing new emerging channels such as live-streaming, WeChat-based group buy and the like.

Rising demand for affordable brands.

After the pandemic, affordable brand products such as cosmetics, apparel and fast food are likely to be popular among consumers as the crisis will lead to an expected income reduction. On the supply side, since China’ exports are affected by the pandemic, manufacturers may re-direct their export production towards the domestic market, creating new, affordable brands for domestic consumption.