Made in the USA: Is it all computers and cars? Economics Spotlight, April 2019

6 minute read

25 April 2019

Patricia Buckley

Patricia Buckley

Last year marked a significant milestone: The volume of manufacturing output finally surpassed its 2007 pre-recession peak. But today’s manufacturing sector differs significantly from yesterday’s both in the industries creating value and how many of us it takes to make it.

The reality and the romance of American manufacturing is at the center of several current public policy controversies, including trade, income inequality, income mobility, and national security. As we pass a milestone more than 10 years in the making, where we are finally manufacturing more than we ever have, we pause to examine the changing composition and employment patterns of a sector that occupies a unique place in the American psyche. We find that gains in manufacturing output have been highly concentrated in just a few industries; the majority of manufacturing industries still contribute less to the economy today than they did 11 years ago.

By 2007, manufacturing in the United States had already undergone significant changes. Over the prior 10 years, the value added by the manufacturing sector had fallen from 16.1 percent of GDP (1997) to 12.8 percent (2007) and its share of total employment had fallen from 14.2 percent to 10.1 percent.1 The relative role of manufacturing further eroded during the recession and into the recovery and, by 2018, manufacturing comprised 11.4 percent of GDP (up slightly from 11.2 percent in 2016 and 2017) and 8.5 percent of total employment. However, even as the role of manufacturing output relative to the size of the economy continued to shrink post-recession, the real value added of the US manufacturing sector slowly recovered and, as of 2018, finally surpassed its 2007 pre-recession peak—the United States now produces more manufactured goods than ever in its history when the impact of price changes, quality and functionality improvements, and intermediate purchases are excluded. Unfortunately, manufacturing employment has not had a similarly positive fate.

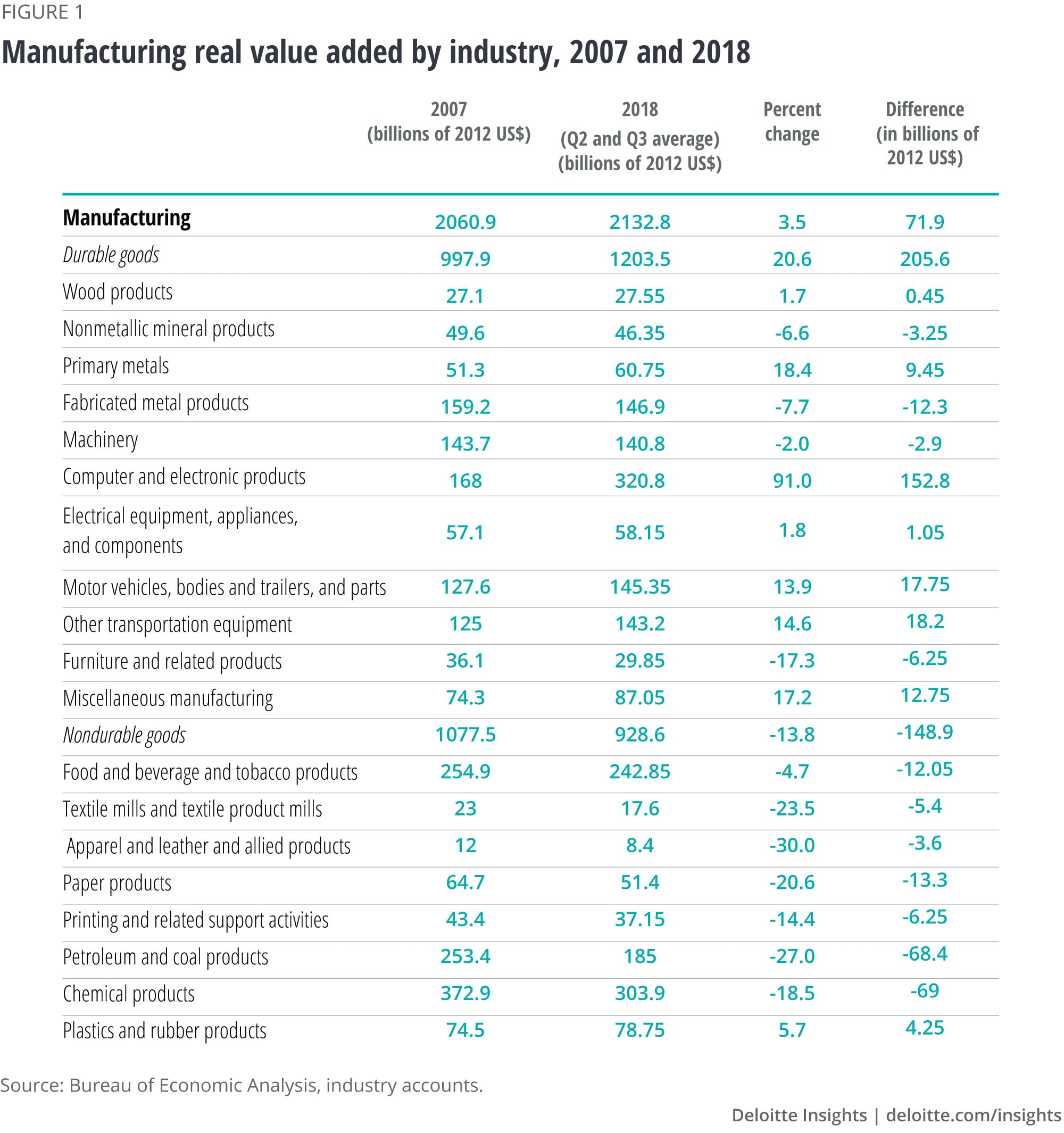

The revival of manufacturing output … for a few industries

As shown in figure 1, the real value added of the manufacturing sector was 3.5 percent higher in 2018 than in 2007 (as of 2017, it was still 1.0 percent lower than 2007), driven by growth in durable goods (real value added by nondurable goods fell during the period). The increase in computer and electronic products more than accounted for the increase in the total value added not only in durable goods, but in manufacturing overall during the period. Other durable goods industries contributing to growth include motor vehicles, trailers, and parts; other transportation equipment (including aerospace products and parts manufacturing, railroad rolling stock manufacturing, and ship and boat building), and primary metals (including the manufacture of iron, steel, and aluminum).2 Among the industries subtracting from real value-added growth in durable goods were furniture and fabricated metals products.

The paths of the durable goods industries that had large percentage increases in real dollar value-added terms between 2007 and 2018 varied considerably, as shown in figure 2. Computers and electronic products was already the largest contributor to GDP among the durable goods industries in 2007 and it almost doubled in size over the period with only a minor slowdown toward the end of the recession. The real value added by the auto sector contracted by 70 percent during the recession before recovering and surpassing its pre-recession level, while the other transportation equipment category held fairly steady before ending 2018 on a positive note. Primary metals manufacturing peaked at the beginning of 2016 and has reversed much of its post-recession gains.

Of the industries in the nondurable goods category, only the plastics and rubber products industry saw any increase over the period; all other nondurable industries reported declines in real value added between 2007 and 2018. However, food and beverage and tobacco manufacturing has been on a strong upswing since the beginning of 2017. One rather surprising result is the large decline in petroleum and coal products manufacturing—which, according to the North American Industrial Classification System, is an industry designated “based on the transformation of crude petroleum and coal into usable products. The dominant process is petroleum refining that involves the separation of crude petroleum into component products through such techniques as cracking and distillation.”3 According to the US Energy Information Agency, US refinery net production of crude oil and petroleum products fell from 5.4 billion barrels in 2007 to 4.3 billion barrels in 2017 (latest data available).4 The value added from the actual production of oil and gas is a mining activity, not a manufacturing activity—and the volume (i.e., real value added) of oil and gas currently extracted is approximately double what it was in 2007.

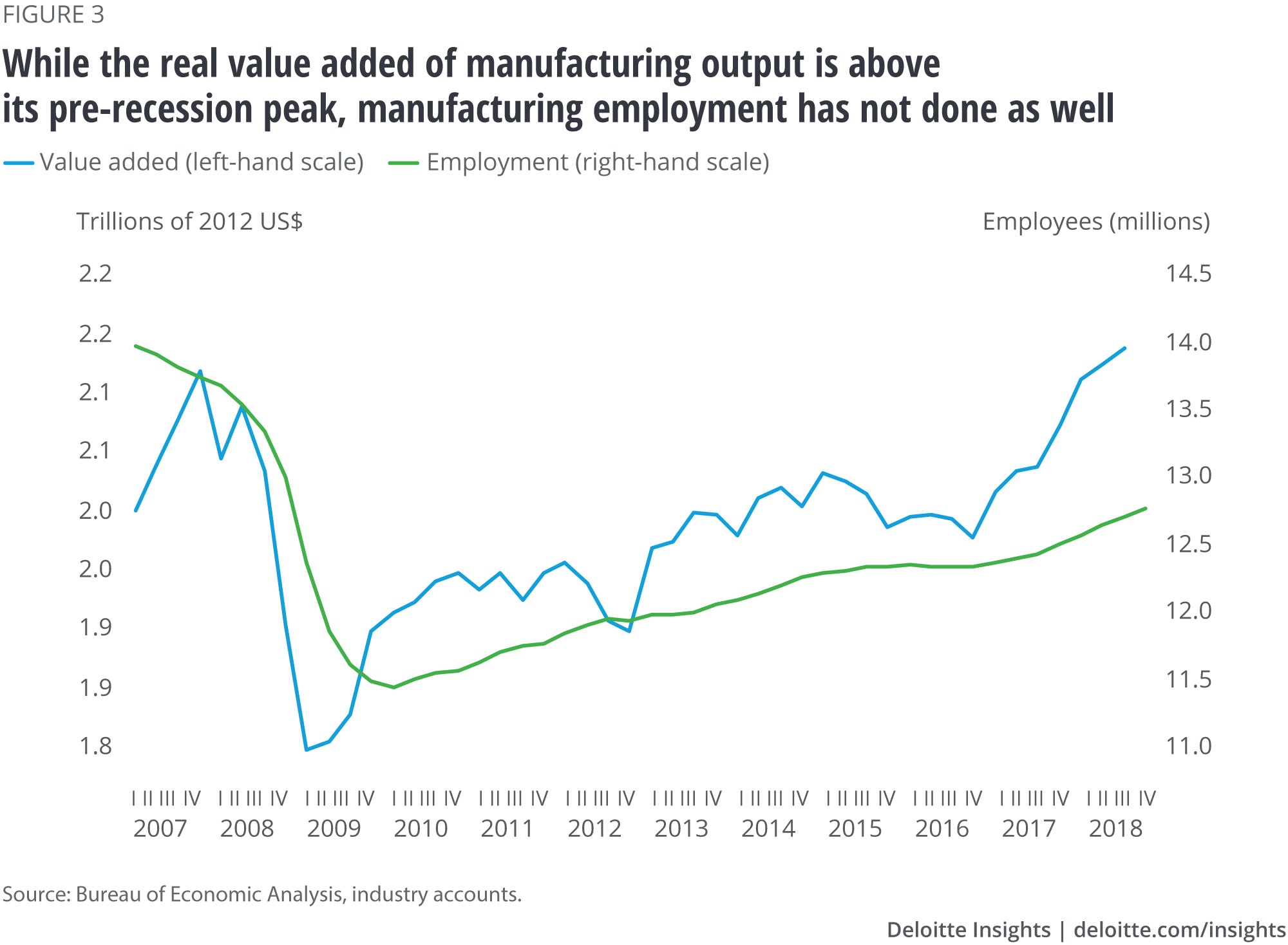

Increasing value of output does not equate to more workers

Even as the proportion of employment accounted for by manufacturing workers continued to decline over the 2007–2018 period, unlike real value-added output, the number of manufacturing workers has not returned to its prerecession levels. Starting with manufacturing employment at just under 14 million workers going into the recession, manufacturing employment reached a low of 11.5 million in 2010. Although the numbers have recovered somewhat, manufacturing employment remained under 13 million in 2018. This contrasts with the behavior of the real value added in manufacturing (figure 3).

Of the individual manufacturing industries, only one—food manufacturing—had more employees in 2018 than it did in 2007 (up 19.1 percent), and this is an industry that had lower real value added in 2018 than it did in 2007. Even the computer and electronic products industry, an industry that almost doubled its real value added between 2007 and 2018, lost 17.1 percent employment over the period, as manufacturers in this industry rapidly automated processes.

When one considers the contribution that manufacturing makes to the US economy, the wide range of growth trajectories followed by the individual US manufacturing industries makes it important to consider separate industries rather than manufacturing as a monolith. The growing contributions from computer and electronic equipment manufacturing and the transportation sector over recession and recovery—and even the more recent turnaround in food manufacturing—should cause us to redefine what manufacturing today looks like. Further, given the divergence between the patterns, the value of output and trends in employment, it would be helpful if those engaged in the policy debates were clear about what aspect of manufacturing they would like to address—more “made in America” or more American “makers.”

© 2021. See Terms of Use for more information.

Explore the Economics collection

-

Rising corporate debt: Should we worry? Article5 years ago

-

Will political tensions derail economic gains in Asia Pacific? Article6 years ago

-

Consumers in advanced economies: A tussle between tailwinds and headwinds Article6 years ago

-

Volatility in emerging economies: Is contagion too harsh a word? Article6 years ago

-

How the financial crisis reshaped the world’s workforce Article6 years ago

-

All in a day’s work—and sleep and play: How Americans spend their 24 hours Article6 years ago