China More economic tensions and heightened uncertainty ahead of trade deal

Even as the United States labeled China a “currency manipulator” on the back of a weakening renminbi, recent trade talks were reported to be “constructive.” This offers hope of a truce in the trade war but tit-for-tat moves by either party can’t be ruled out.

The US Federal Reserve’s dovish stance is a respite to most emerging markets including China, but the People’s Bank of China’s (PBOC) move to bring the renminbi (RMB) below 7.0 per US dollar—a key psychological threshold—may have profound global implications. It is arguably sensible for China to rely on the renminbi exchange rate as a monetary lever at a time when the movement of short-term interest rates could become constrained by the zero lower bound, due to the continued process of interest rate liberalization in the country. Of course, should the US-China trade war drag on and escalate with tit-for-tat moves from both sides, it would also be logical for China to unveil measures that could offset higher tariffs. In the long run, a truce in the trade war is needed so that wounded investment sentiment can gradually heal.

Learn more

Read the Weekly Global Economic Update

Explore Economic Outlooks: Asia Pacific

Subscribe to receive related content

Download the Deloitte Insights and Dow Jones app

It may sound like a cliché, but the fact remains that data for the first half of 2019, reflecting a GDP growth rate of 6.3 percent,1 clearly indicates the resilience of the Chinese economy. If the economy remains on track in the second half of 2019, GDP growth will hit the government’s target of around 6.2 percent.2 While this is the lowest it has been in more than two decades, China’s economy today is huge—US$13.6 trillion or 13.2 times the size it was in 1998.3 In 1998—the height of the Asian financial crisis—China had pledged to maintain a GDP growth rate of 8 percent and not to devalue the renminbi.

But more important than the figures is the major lesson Beijing has learnt from its recent trade war with the United States—that fiscal stimulus not only has a diminishing impact on economic growth but can also exacerbate trade tensions. This is what happened in 2008 as well; therefore, pundits in Beijing are now well aware of the fact that in China, fiscal stimulus tends to favor big-ticket infrastructure projects, but the effect is temporary. Moreover, the side effects of fiscal stimuli, including higher leverage and trade tensions caused by China’s surging exports and state subsidies, can end up creating serious economic imbalances down the road.

What, then, should Beijing’s response be to the present global economic downturn? The current state of the Chinese economy—H2 is likely to see mild deceleration, but the growth target of around 6.2 percent remains on track—does not warrant a strong dose of countercyclical policies. The top item on the policy agenda for China is to strike a trade deal with the United States. Would the best policy response for China, then, be to do nothing at all in the global backdrop of monetary easing by many central banks?

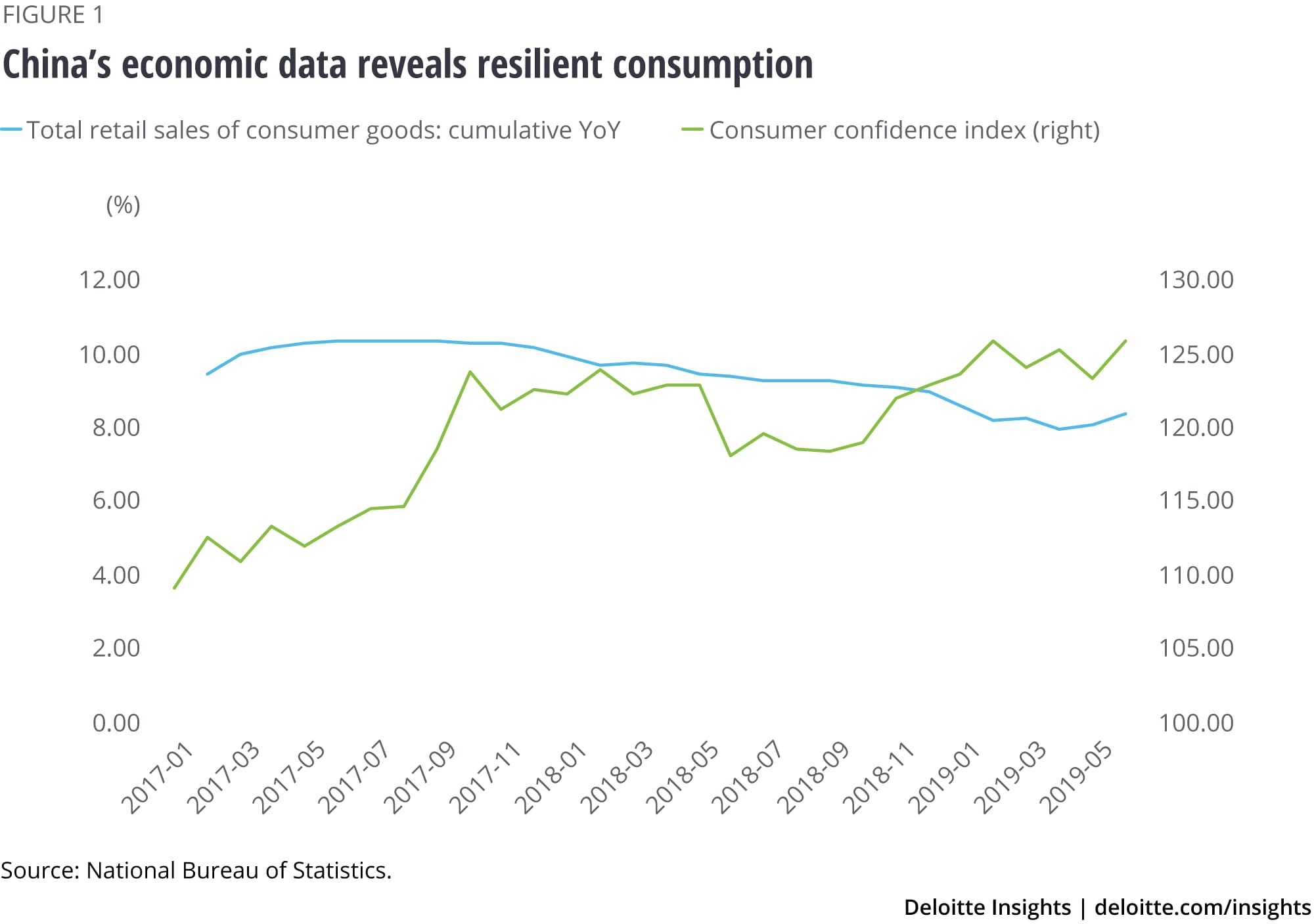

Consumption resilient despite external shocks

If we dissect the major economic data from H1, consumption remains the brightest sector in China, with retail sales showing an increase of 8.4 percent.4 However, it is our firm belief that retail sales would better reflect the real state of the economy if auto sales (down over 12 percent in H1)5 were not taken into account. Investment has also held up, growing by more than 5 percent in the first half of the year.6 In particular, investment in property has risen by almost 11 percent7—and this is in spite of the fact that most major developers have reported great difficulties in funding their projects.

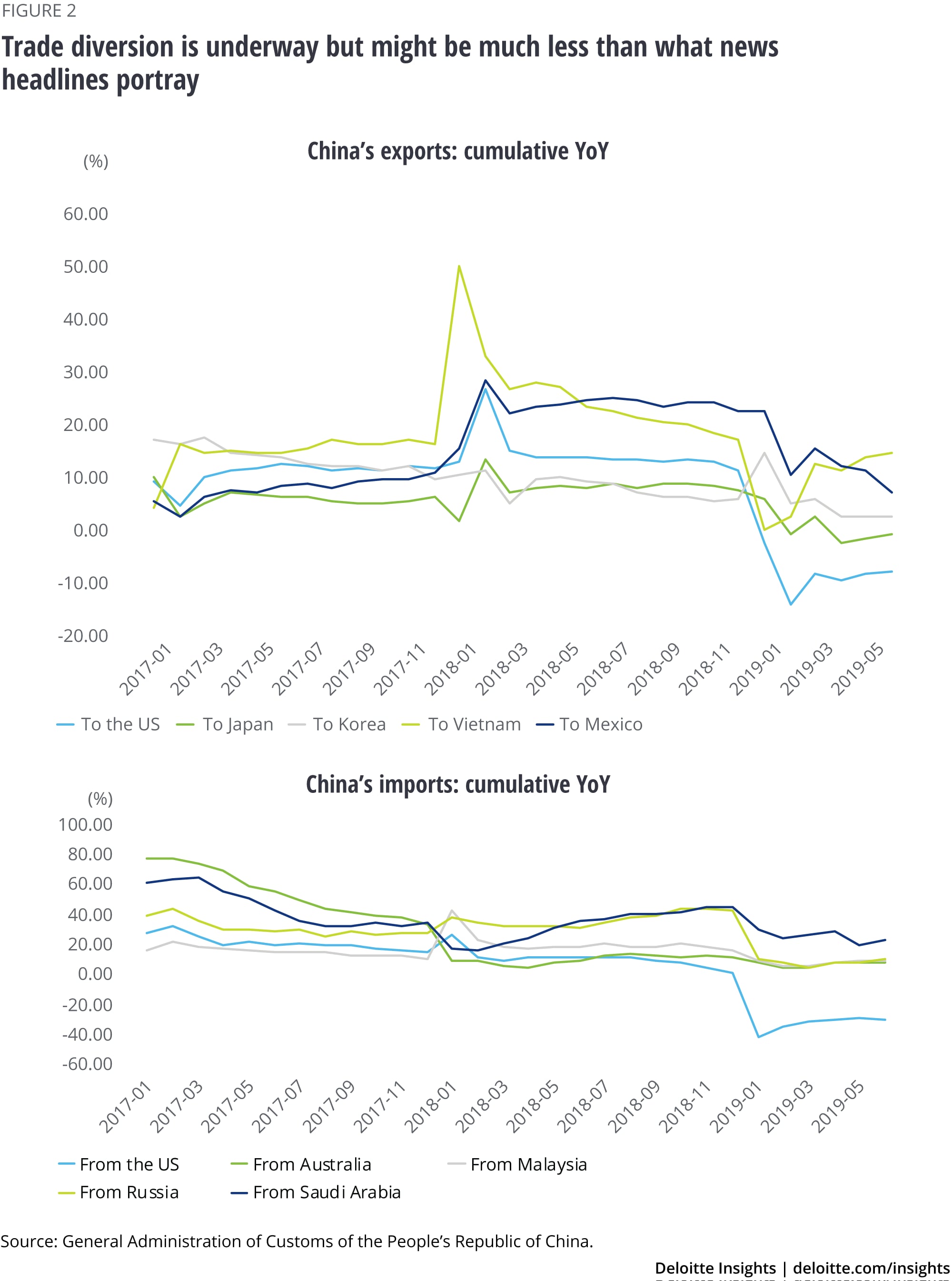

As expected, the external sector has been the most affected by the trade war. US exports to China fell by almost 30 percent in H1, and China’s exports to the United States—China’s largest market—dropped disappointingly by 8.1 percent, due to 25 percent tariffs on more than US$200 billion of Chinese exports.8 It seems that trade diversion is underway in China with more exports to Vietnam and Mexico. Besides, China’s exports to Japan and Korea, its No. 3 and No. 4 overseas markets, respectively, were relatively steady in H1 with minor shifts of –1.1 percent and 2.5 percent, respectively.9

All in all, China’s economic resilience is underpinned by confident consumers and ample policy leeway (beyond fiscal levers). To be more specific, fiscal levers could be in the form of higher spending on a social safety net and tax cuts for enterprises.

But a meaningful step toward a managed float of the renminbi exchange rate regime will allow the PBOC to have a more effective monetary policy in the long run. From this perspective, the event in which US dollar-renminbi exchange exchange rate broke 7.0 on Aug. 5 was warranted. It continued to edge higher on the PBOC’s eased control and latest trade war salvos. (The U.S. Department of the Treasury designated China as a “currency manipulator” on the same day.)10

PBOC’s response to global monetary easing

The question, then, is: Should Chinese policymakers take out insurance to underwrite growth if the external sector faces more shocks in the second half of the year? Despite the rate cut of 25 basis points on July 31,11 the Fed is likely to slash the federal funds rate by another 25 basis points in H2 2019. The Fed’s dovish stance, which was initially prompted by a potential economic slowdown in the United States and trade tensions, was later reinforced by the European Central Bank’s return to quantitative easing.

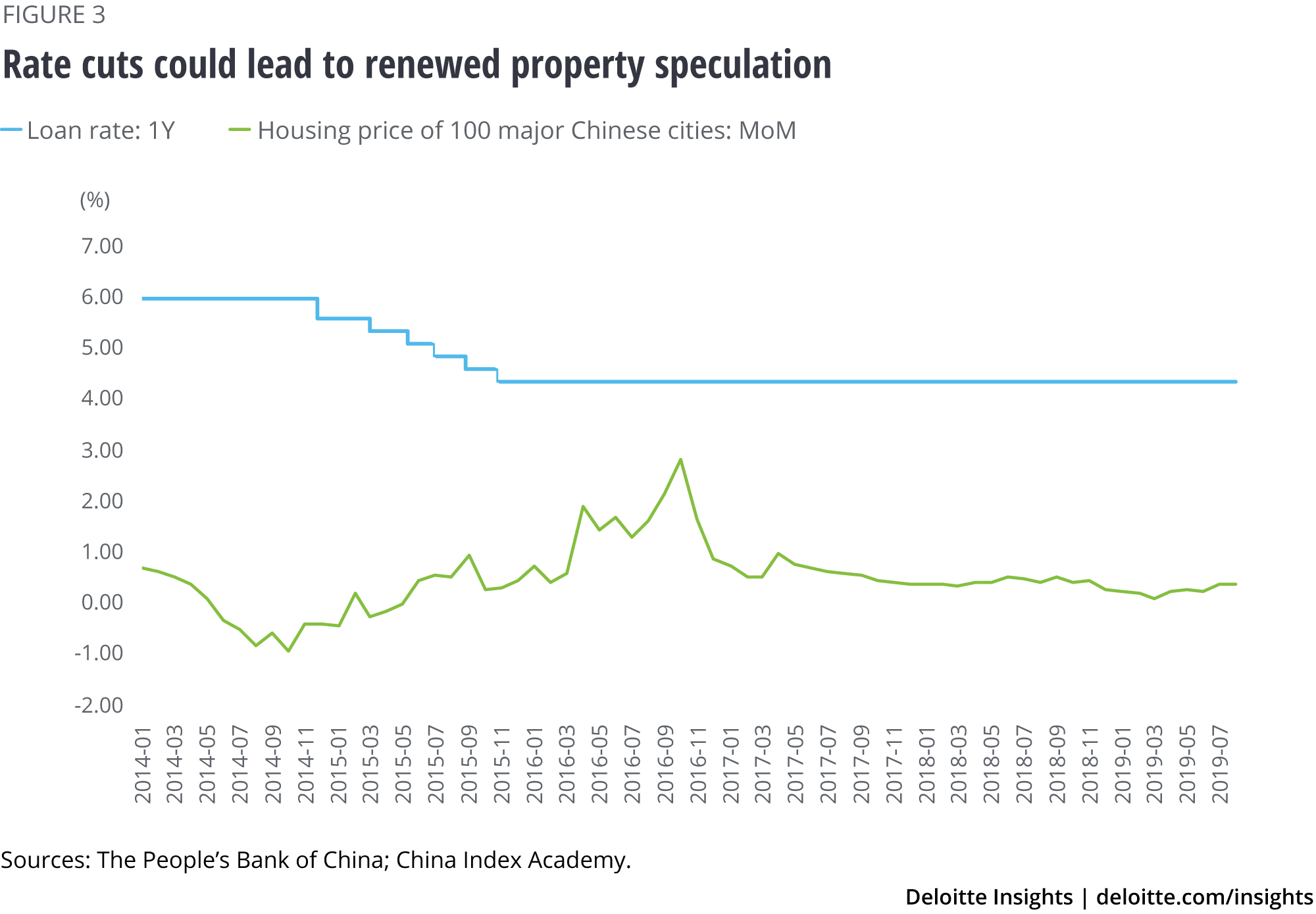

So, should the PBOC lower interest rates as some of the region’s central banks (e.g., Bank of Korea and Bank Indonesia) have done? The short answer is not yet. Although inflation is not an imminent threat (as oil prices are low) and rate cuts are unlikely to trigger capital outflows this time around (they were caused principally by poor market sentiment in the past two years), lowering interest rates won’t address the fundamental issue. This issue is a lack of access to credit by the private sector and SMEs who are suffering from a severe credit crunch due to ongoing economic and financial restructuring.12 Moreover, if the PBOC joins other central banks in their monetary easing exercise, instead of guiding money toward SMEs, it could end up leading to renewed speculation in the property sector—exactly what policymakers have been striving to avoid.

Hence, it is our belief that the PBOC will only cut reserve requirement rates (at least twice this year) and lower the yields of various money market instruments in an effort to enhance liquidity conditions, if necessary. Against the backdrop of global easing, the PBOC should move to a slightly more flexible rate regime or a managed float, but not a free float by any means. The market, of course, is expecting further weakness in the renminbi because the forex market is more prone to momentum trading in the short run.

So, it is more important for China to open up its domestic market. But one cannot rule out the possibility of “black swan” or “gray rhino” events occurring. What if, for example, tit-for-tat moves by China (state firms were asked to stop buying US agricultural products, according to CNBC) and the United States (10 percent tariffs on US$300 billion of Chinese exports could be introduced) bring on a global stock markets crash?

China’s stance after the latest “constructive” trade talks

The 12th round of US-China trade talks in Shanghai (July 30 and 31) ended early with a mutual acknowledgment of “having had constructive talks” and a clearly stated commitment from China to purchase more US agricultural products.13 However, on Aug. 2, US President Donald Trump announced a new set of tariffs—10 percent—on US$300 billion worth of Chinese exports, which is to come into force on Sept. 1.14 The tariffs were revised on the grounds that China did not live up to its promises. Immediately, US asset markets reacted negatively—stock values went down, bond yields fell, and oil prices also dropped sharply, contributing to an even dimmer economic outlook for the United States for the remainder of the year. More significantly, while China’s A-shares also reacted negatively, share prices of rare earth went up, bucking the trend and reflecting investors’ expectations of retaliatory tariffs from China.

But there is still some space for optimism. The fact that both the United States and China have used the word “constructive” to describe the last round of trade talks, which at least did not collapse, demonstrates that both sides are aware that they can’t ignore ground realities. It would be unrealistic for the United States to imagine that China can fundamentally alter its economic model even in the medium term. But China also needs to understand and address certain grievances of its major trading partners—especially as some requests from the United States, such as more effective protection of intellectual property and better access for foreign goods and services to the vast domestic market, are very much in line with China’s own reform objectives.

The escalation, after the latest round of trade talks in Shanghai, does beg the question: “What has caused the impasse?” Both sides have raised concerns—such as imposition of trade tariffs, the deal negotiation process, the Huawei dispute, and agricultural trade expectations—that have challenged their ability to trust each other.

We are still confident that a trade deal can be struck before 2020 because an escalation of trade tension is not in either party’s interest. A deal isn’t guaranteed, of course. A resolution with Huawei would be seen positively by China. And, for its part, China can easily—if it wants to—step up its purchase of US agricultural products. But even if the United States could achieve a so-called fairer trade or balanced trade with China, it may not be the optimal outcome for both countries. If Washington and Beijing engage in a grand managed trade, in which China guarantees to buy certain US products in exchange for access to the largest consumer market, the end result would be detrimental to the global trading system.

For example, there could well be substitution of trade in agricultural and energy products. If China wants to avoid a large current account deficit (say, 2–3 percent of the GDP) and is constrained by political reasons to maintain a stable renminbi exchange rate, it may well adopt measures to curtail imports. In such a scenario, we could see more trade frictions between China and its other trading partners. Therefore, it is still in the country’s best interests to cut tariffs close to the level of developed countries. In the short run, global companies are likely to adopt a wait-and-watch approach when it comes to changes in supply chains. (Over 60 percent of US companies in China don’t have plans to relocate manufacturing facilities, according to an AmCham survey.)15 But if trade talks drag on, average tariffs on China’s exports to the United States could conceivably force many global companies to reevaluate their supply chains.

What could China do to mitigate such disruptions? Local governments are expected to roll out various relief measures such as subsidies and tax rebates. However, from the central government’s standpoint, agonizing trade talks may have raised a deeper question—how to entice global companies to invest more into China’s domestic market where there is ample demand unmet.

Explore more economics content

-

All in a day’s work—and sleep and play: How Americans spend their 24 hours Article6 years ago

-

United States Economic Forecast Q4 2024 Article1 week ago

-

Rising corporate debt: Should we worry? Article5 years ago

-

Canada Economic Outlook Article4 years ago

-

United States Economic Forecast Q4 2024 Article1 week ago

-

Japan economic outlook, October 2024 Article2 months ago